Anderson's Rule 11 Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

82791 Li 19359

l 19359 li 82791 COUNTRY MUSIC 1 986 COMING SOON TO CASH BOX Week in, week out, CASH BOX presents the most comprehensive and authoritative coverage of Country Music. Year in, year out, the CASH BOX annual CMA issue brings industry acclaim as the most authoritative source for information. This year, in step with Country Music's spectacular impact on radio, television, films and records. CASH BOX presents the ultimate salute to NASHVILLE. COUNTRY MUSIC 1 986 It's the perfect vehicle for your advertising message Reserve ad space for bonus distribution in Nashville during COUNTRY MUSIC WEEK Advertising deadline, October I, 1986 Issue date, October 18, 1986 RESERVE YOUR AD SPACE FOR BEST POSITION NOW! CONTACT: J. B. CARMICLE TOM McENTEE SPENCE BERLAND It (212) 586-2640 (615) 244-2898 (213) 464-8241 CASHBOX \ITERNATIONAL MUSIC/COIN MACHINE/HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME L—NUMBER 1 2—SEPTEMBER 6, 1986 “Hey . Let’s Start ASHBOX Our Own Record Company.’’ )RGE ALBERT By Larry Rosen nt and Publisher Question: Can two musicians start a record company and make and of course, Dave Grusin. At this point, the independents had lost tK ALBERT esident and Managing Editor the venture profitable? all their major labels, and they said to us, “We need you.” After NCE BERLAND Answer: Yes. many meetings, we felt this was a good marriage. esident I’m happy to say, at GRP Records this is the case. After working Three Years Later. CARMICLE together as musicians, then producing albums together for “third 1 must say, it can be done. The opportunities are there for cre- esident party” record companies, and then a venture called “Artista/GRP ative people coming from either the music side or the business side ERT LONG Records”, Dave Grusin and I had come to the point of taking the to create their own entity and become successful. -

School Dedicated to Late Student Red & Blue Turns Pink for Oct. DU Law School Helps Convicts

October 13, 2016 Volume 96 Number 9 THE DUQUESNE DUKE www.duqsm.com PROUDLY SERVING OUR CAMPUS SINCE 1925 School Red & Blue turns pink for Oct. DU law dedicated school to late helps student convicts RAYMOND ARKE CAROLYN CONTE asst. news editor staff writer This past summer, non-profit or- Innocent until proven guilty is the ganization Food for the Poor built standard for the American criminal a school in Nicaragua in memory justice system. However, that process of a Duquesne student who passed can sometimes fail, resulting in inno- away in 2014. cent people going to jail. A 2014 study The newly-founded St. Kateri published in The Proceedings of the Tekakwitha School will serve chil- National Academy of Sciences sug- dren in the village of Jicaro, Nica- gests 4 percent of prisoners on death ragua. The school is dedicated to row, a relatively small population in Sara Sawick, who was a sophomore prisons, may be innocent. Duquesne liberal arts student when she died students can now be part of a nation- unexpectedly two years ago. wide effort to exonerate innocent in- In 2013, Sara Sawick traveled to mates. Nicaragua with Food for the Poor, The Pennsylvania affiliate of the In- a non-profit organization which nocence Project, a nationwide organi- builds homes for impoverished zation which works to help free those communities, like the families wrongly convicted, has just recently of Jicaro. Although Food for the opened an office in Duquesne’s Tri- Poor has given Nicaraguans many bone Center, which gives Duquesne homes, the families of Jicaro still and Pitt law students the ability to RACHAEL STRICKLAND/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER did not have a school. -

Download Album the Cheif Jidenna Download Album the Cheif Jidenna

download album the cheif jidenna Download album the cheif jidenna. Wondaland Records presents the sharp dresser, singer, and rapper, Jidenna Mobisson who releases a whole lot of six brand new songs off his recently released extended play album tagged the Boomerang EP. Hip-hop act Jidenna has unveiled the entire songs his EP titled, Boomerang and which makes a rich representation of the Nigerian music with Tiwa Savage, Maleek Berry, Burna Boy, Sarkodie and Wale while featured as guest artistes while other International singers such as Quavo and Dot Cromwell were also featured as guest artistes. Jidenna had earlier released his debut album titled ‘The Chief’ in February 2017, and the album made was Mobisson’s first album ever. The Boomerang consist of six tracks in total, two of which are remixes to his hit tracks; Little Bit More and Bambi. Jidenna delivered a boastful and foul-mouthed rhymes on the neat vocal hook over a sparse of some street-level beat in all the single off his Boomerang EP. Download album the cheif jidenna. DOWNLOAD LINK HERE - Jidenna – The Chief Full Album leak Download link MP3 ZIP RAR. Year: 2017 Artist: Jidenna Album: The Chief Genre: Contemporary R&B, Hip Hop, R&B. Track list: 1. A Bull’s Tale 2. Chief Don’t Run (feat. Roman GianArthur) 3. Trampoline 4. Bambi 5. Helicopters / Beware 6. Long Live the Chief 7. 2 Points 8. The Let Out (feat. Nana Kwabena) 9. Safari (feat. Janelle Monáe, St. Beauty & Nana Kwabena) 10. Adaora 11. Little Bit More 12. Some Kind of Way 13. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

Harmonizing the Liner Notes: How the USCO's Adoption of Metadata

Chicago-Kent Journal of Intellectual Property Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 2 2-8-2019 Harmonizing the Liner Notes: How the USCO’s Adoption of Metadata Standards Will Improve the Efficiency of Licensing Agreements for Audiovisual Works Michael Reed The Law Office of Michael Reed Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/ckjip Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Reed, Harmonizing the Liner Notes: How the USCO’s Adoption of Metadata Standards Will Improve the Efficiency of Licensing Agreements for Audiovisual Works, 18 Chi. -Kent J. Intell. Prop. 23 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/ckjip/vol18/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Journal of Intellectual Property by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. HARMONIZING THE LINER NOTES: HOW THE USCO’S ADOPTION OF METADATA STANDARDS WILL IMPROVE THE EFFICIENCY OF LICENSING AGREEMENTS FOR AUDIOVISUAL WORKS MICHAEL REED* It is no secret that making a living as a musician is not as lucrative of a proposition as it was a generation ago. For this reason, musicians have had to diversify their sources of income. Placement of a song in advertisements, film, or television programs have become an integral part of many successful musician’s careers, but far too many independent artists still find these opportunities out of reach. -

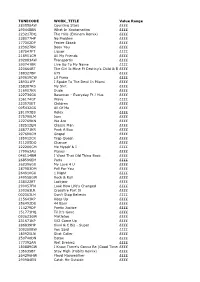

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

Rose City Mobile Music

Current as of 1/5/2018 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title ~ Black rows are new additions # 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 311 Til The City's On Fire 0:00 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Creepers 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 0:00 The Sound (Clean Edit) 0:00 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) (Hed) P.E. Closer (Clean Radio Edit) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years Novacaine 12 Stones Broken Road 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975.. Chocolate 1975.. Girls (Warning Content) 1Love f Corey Hart Truth Will Set U Free 2 Chainz Crack (Warning Content) 2 Chainz I'm Different (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Riot (Clean Edit) 2 Chainz Spend It (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Used 2 (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Watch Out (Clean Edit) (Warning Extreme Content) 2 Chainz f Cap 1 Where U Been (Clean Edit) (Warning Extreme Content) 2 Chainz f Drake No Lie (Clean Edit) (Warning Content) 2 Chainz f Drake Big Amount (Clean Edit) (Warning Content) 2 Chainz -

Developing the Digital Marketplace for Copyrighted Works

In the Matter of: Developing the Digital Marketplace for Copyrighted Works March 28, 2019 Third Public Meeting Condensed Transcript with Word Index For The Record, Inc. (301) 870-8025 - www.ftrinc.net - (800) 921-5555 Third Public Meeting Developing the Digital Marketplace for Copyrighted Works 3/28/2019 1 3 1 1 WELCOME REMARKS 2 2 MS. ALLEN: So good morning. If we could 3 3 just start getting started and sitting down in our 4 DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE 4 seats, I’ll give a few housekeeping notes and then 5 5 introduce Shira, and then we’ll begin. 6 INTERNET POLICY TASK FORCE 6 So just while you're getting seated, I'll 7 7 give an overview of the day. We’ll have coffee and 8 DEVELOPING THE DIGITAL MARKETPLACE 8 tables set up in the room next door, so if you want to 9 9 have sidebar conversations -- or, actually, there's 10 FOR COPYRIGHTED WORKS 10 coffee here as well. 11 11 The restrooms are out to the right, and we 12 THIRD PUBLIC MEETING 12 just ask that everyone here register by signing in up 13 13 front. If you haven’t already, please do so. We did 14 14 sort of take an informal poll of people who might be 15 THURSDAY, MARCH 28, 2019 15 interested in a happy hour nearby, so that’s on the 16 16 registration list. We’d like to have a headcount by 17 17 noon, if we could, for the restaurant. 18 U.S. PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE 18 And with that, I think I’d just like to say 19 600 DULANY STREET 19 welcome, and it's my honor to introduce Shira 20 ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22313-1450 20 Perlmutter, who will provide opening remarks. -

Music 2025 the Music Data Dilemma: Issues Facing the Music Industry in Improving Data Management

Music 2025 The Music Data Dilemma: issues facing the music industry in improving data management Research commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office and carried out by Ulster University: Professor Frank Lyons, Dr Hyojung Sun, Dennis Collopy, Paul O’Hagan and Professor Kevin Curran. Findings and opinions are those of the researchers, not necessarily the views of the IPO or the Government. Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office Music 2025 Core Research Team: ISBN: 978-1-910790-40-3 Music 2025: The Music Data Dilemma: issues facing Professor Frank Lyons is Dean of Research and Impact in Arts, Humanities the music industry in improving data management and Social Sciences at Ulster University. He has developed an international profile as a composer and researcher with over 150 performances and Published by The Intellectual Property Office exhibitions of his works in China, Japan, Australia, South Africa, the US, June 2019 Europe, the UK and Ireland and broadcast on BBC, RTE, NPR and ABCFM, performed by some of the world’s leading soloists and ensembles. He has 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 also developed an international network of research collaborations in the field of creative technologies and disability under the ‘Inclusive Creativity’ banner. © Crown Copyright 2019 Professor Lyons is currently Co-Director of Ulster’s Creative Industries Institute and Co-Director (Partnerships) of Future Screens NI, a collaboration with QUB You may re-use this information (excluding logos) and a number of key industrial partners which secured £13million from AHRC free of charge in any format or medium, under the and industry to drive growth in the creative economy in the region.