Louisiana Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermal Toxicity Literature Evaluation

Thermal Toxicity Literature Evaluation 2011 TECHNICAL REPORT Electric Power Research Institute 3420 Hillview Avenue, Palo Alto, California 94304-1338 • PO Box 10412, Palo Alto, California 94303-0813 USA 800.313.3774 • 650.855.2121 • [email protected] • www.epri.com Thermal Toxicity Literature Evaluation 1023095 Final Report, December 2011 EPRI Project Manager R. Goldstein ELECTRIC POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 3420 Hillview Avenue, Palo Alto, California 94304-1338 ▪ PO Box 10412, Palo Alto, California 94303-0813 ▪ USA 800.313.3774 ▪ 650.855.2121 ▪ [email protected] ▪ www.epri.com DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTIES AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITIES THIS DOCUMENT WAS PREPARED BY THE ORGANIZATION(S) NAMED BELOW AS AN ACCOUNT OF WORK SPONSORED OR COSPONSORED BY THE ELECTRIC POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE, INC. (EPRI). NEITHER EPRI, ANY MEMBER OF EPRI, ANY COSPONSOR, THE ORGANIZATION(S) BELOW, NOR ANY PERSON ACTING ON BEHALF OF ANY OF THEM: (A) MAKES ANY WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION WHATSOEVER, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, (I) WITH RESPECT TO THE USE OF ANY INFORMATION, APPARATUS, METHOD, PROCESS, OR SIMILAR ITEM DISCLOSED IN THIS DOCUMENT, INCLUDING MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR (II) THAT SUCH USE DOES NOT INFRINGE ON OR INTERFERE WITH PRIVATELY OWNED RIGHTS, INCLUDING ANY PARTY'S INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, OR (III) THAT THIS DOCUMENT IS SUITABLE TO ANY PARTICULAR USER'S CIRCUMSTANCE; OR (B) ASSUMES RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY WHATSOEVER (INCLUDING ANY CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, EVEN IF EPRI OR ANY EPRI REPRESENTATIVE HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES) RESULTING FROM YOUR SELECTION OR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT OR ANY INFORMATION, APPARATUS, METHOD, PROCESS, OR SIMILAR ITEM DISCLOSED IN THIS DOCUMENT. -

Interdunal Wetland

Interdunal Wetland (Global Rank G2?; State Rank S1) Overview: Distribution, Abundance, Environmental Setting, Ecological Processes !( !( !( Interdunal Wetland is an extremely rare natural community in Wisconsin, where it is restricted to a small number of sites on Great Lakes coasts. By definition, these commu- nities are associated with and dependent on Great Lakes dunes in which wind, water, or currents have created hollows between the dunes or beach ridges that intersect the water !( table. Such sites are colonized by a distinctive assemblage of wetland plants, which include habitat specialists of high con- servation significance because of their rarity, habitat needs, or limited distribution. All Wisconsin occurrences are small, seldom encompass- !( ing more than 10 acres. Great Lakes shoreline environments are extremely dynamic, and interdunal wetlands will shift in !( size, shape, and location as the dunes themselves move. As long as the shoreline processes of sand movement, deposi- tion, and erosion remain functional, new interdunal wetlands will be created as others are destroyed. On Lake Superior, Interdunal Wetlands are associated with sandspits and baymouth bars, which may support low dunes of less than one to several meters in height. The configura- Locations of Interdunal Wetland in Wisconsin. The deeper hues tions of these wetlands may change radically depending on shading the ecological landscape polygons indicate geographic Lake Superior water levels, and the frequency, severity, and areas of greatest abundance. An absence of color indicates that approach direction of major storms. There is at least one Lake the community has not (yet) been documented in that ecological Superior site where human excavations on a sandspit have landscape. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Fishes of New Mexicoi

Threatened and Endangered Fishes of New MexicoI BY DAVID L. PROPST ILLUSTRATED BY W. HOWARD BRANDENBURG MAPS BY AMBER L. HOBBES ◆ EDITED BY PAUL C. MARSH TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 1 1999 NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF GAME AND FISH STATE OF NEW MEXICO: Gary E. Johnson, Governor STATE GAME COMMISSION: William H. Brininstool, Chairman ◆ Jal Gail J. Cramer ◆ Farmington Steve Padilla ◆ Albuquerque Dr. William E. Schuler ◆ Albuquerque George A. Ortega ◆ Santa Fe Bud Hettinga ◆ Las Cruces Stephen E. Doerr ◆ Portales DEPARTMENT OF GAME AND FISH: Gerald A. Maracchini, Director CONSERVATION SERVICES DIVISION: Andrew V. Sandoval, Chief $10.00 1999 Threatened and Endangered FISHES of New Mexico ◆ 1 Propst, D.L. 1999. Threatened and endangered fishes of New Mexico. Tech. Rpt. No. 1. New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM. 84 pp. Cover by NoBul Graphics, Albuquerque, NM. Design and production by Janelle Harden, The Studio, Albuquerque, NM. Publication and printing supported by the Turner Foundation, Atlanta, GA. In part, a contribution of Federal Aid in Fish and Wildlife Restoration., Project FW–17–RD. Contents may be reprinted if credit is given to the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. Complete copies may be purchased for $10.00 U.S. (see address below). Make checks payable to “New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.” Conservation Services Division New Mexico Department of Game and Fish P.O. Box 25112 Santa Fe, NM 87504 (505) 827-7882 2 ◆ New Mexico Department of Game and Fish FORWARD Threatened and Endangered Fishes of New a major concern. Over half of the rivers in New Mexico Mexico by Dr. -

Status Review and Surveys for Frecklebelly Madtom, Noturus Munitus

Noturus munitus, Buttahatchee R., Lowndes Co., AL Final Report: Status review and surveys for Frecklebelly Madtom, Noturus munitus. David A. Neely, Ph. D. Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute 175 Baylor School Rd Chattanooga, TN 37405 Background: The frecklebelly madtom, Noturus munitus, was described by Suttkus & Taylor (1965) based largely on specimens from the Pearl River in Louisiana and Mississippi. At that time, the only other known populations occupied the Cahaba and Upper Tombigbee rivers in Alabama and Mississippi. Populations were subsequently discovered in the Alabama, Etowah, and Conasauga rivers (Bryant et. al., 1979). The disjunct distribution displayed by the species prompted an examination of morphological and genetic differentiation between populations of frecklebelly madtom. Between 1997-2001 I gathered morphological, meristic, and mtDNA sequence data on frecklebelly madtoms from across their range. Preliminary morphological data suggested that while there was considerable morphological variation across the range, the populations in the Coosa River drainage above the Fall Line were the most distinctive population and were diagnosable as a distinct form. I presented a talk on this at the Association of Southeastern Biologists meeting in 1998, and despite the lack of a formal description, the published abstract referring to a "Coosa Madtom" made it into the public 1 eye (Neely et al 1998, Boschung and Mayden 2004). This has resulted in substantial confusion over conservation priorities and the status of this form. The subsequent (and also unpublished) mitochondrial DNA data set, however, suggested that populations were moderately differentiated, shared no haplotypes and were related to one another in the following pattern: Pearl[Tombigbee[Cahaba+Coosa]]. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

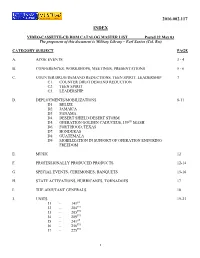

Video Catalog Master List

2016.002.117 INDEX VIDEO-CASSETTE-CD ROM CATALOG MASTER LIST Posted 22 May 03 The proponent of this document is Military Library – Earl Santos (Col. Ret) CATEGORY SUBJECT PAGE A. ACOE EVENTS 3 - 4 B. CONFERENCES, WORKSHOPS, MEETINGS, PRESENTATIONS 5 - 6 C. COUNTER DRUG/DEMAND REDUCTIONS, TEEN SPIRIT, LEADERSHIP 7 C1. COUNTER DRUG DEMAND REDUCTION C2. TEEN SPIRIT C3. LEADERSHIP D. DEPLOYMENTS/MOBILIZATIONS 8-11 D1. BELIZE D2. JAMAICA D3. PANAMA D4. DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM D5. OPERATION GOLDEN CADUCEUS, 159TH MASH D6. FORT HOOD, TEXAS D7. HONDURAS D8. GUATEMALA D9 MOBILIZATION IN SUPPORT OF OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM E. MUSIC 12 F. PROFESSIONALLY PRODUCED PRODUCTS 12-14 G. SPECIAL EVENTS, CEREMONIES, BANQUETS 15-16 H. STATE ACTIVATIONS, HURRICANES, TORNADOES 17 I. THE ADJUTANT GENERALS 18 J. UNITS 19-23 J1 - 141ST J2 - 204TH J3 - 205TH J4 - 209TH J5 - 241ST J6 - 256TH J7 - 225TH 1 2016.002.117 J8 - 5TH ARMY J9 - 528th J10 - 1083rd J11 - 527th J12 - 244THAA J13 - 812th J14 - 61st TROOP COMMAND J15 - 769th J16 - 1/156th INFANTRY J17 - 2/156TH INFANTRY J18 - 159 ARMY BAND J19 - 159 MASH J20 - 773 TANK DESTROYER BN K. WW II 24-25 L. YOUTH CHALLENGE PROGRAM (YCP) 26-27 M. JACKSON BARRACKS MILITARY HISTORY 28-29 M1. -JACKSON BARRACKS MILITARY MUSEUM, NOLA M2. -JACKSON BARRACKS MILITARY LIBRARY, NOLA M3. -JACKSON BARRACKS, NOLA M4. -CAMP BEAUREGARD MILITARY MUSEUM, PINEVILLE, LA M5. -GILLIS W. LONG CENTER, CARVILLE, LA N. AIR NATIONAL GUARD 30 O. COMMUNITY PROJECTS 31-32 O1 - GUARD CARE O2 - CLEAN SWEEP O3 - MAISON ORLEANS O4 - UNITED WAY O5 - SPECIAL OLYMPICS O6 - REEF-EX O7 - CHRISTMAS TREE RECYCLING O8 - EMPLOYER SUPPORT GUARD RESERVE (ESGR) O9 - D-DAY PARADE P. -

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN)

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

The Fern Family Blechnaceae: Old and New

ANDRÉ LUÍS DE GASPER THE FERN FAMILY BLECHNACEAE: OLD AND NEW GENERA RE-EVALUATED, USING MOLECULAR DATA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Vegetal do Departamento de Botânica do Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Biologia Vegetal. Área de Concentração Taxonomia vegetal BELO HORIZONTE – MG 2016 ANDRÉ LUÍS DE GASPER THE FERN FAMILY BLECHNACEAE: OLD AND NEW GENERA RE-EVALUATED, USING MOLECULAR DATA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Vegetal do Departamento de Botânica do Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Biologia Vegetal. Área de Concentração Taxonomia Vegetal Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alexandre Salino Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Vinícius Antonio de Oliveira Dittrich Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora BELO HORIZONTE – MG 2016 Gasper, André Luís. 043 Thefern family blechnaceae : old and new genera re- evaluated, using molecular data [manuscrito] / André Luís Gasper. – 2016. 160 f. : il. ; 29,5 cm. Orientador: Alexandre Salino. Co-orientador: Vinícius Antonio de Oliveira Dittrich. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Departamento de Botânica. 1. Filogenia - Teses. 2. Samambaia – Teses. 3. RbcL. 4. Rps4. 5. Trnl. 5. TrnF. 6. Biologia vegetal - Teses. I. Salino, Alexandre. II. Dittrich, Vinícius Antônio de Oliveira. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Departamento de Botânica. IV. Título. À Sabrina, meus pais e a vida, que não se contém! À Lucia Sevegnani, que não pode ver esta obra concluída, mas que sempre foi motivo de inspiração. -

2021 Louisiana Recreational Fishing Regulations

2021 LOUISIANA RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS www.wlf.louisiana.gov 1 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO CONTENTS 6. LICENSING 9. DEFINITIONS DON’T 11. GENERAL FISHING INFORMATION General Regulations.............................................11 Saltwater/Freshwater Line...................................12 LITTER 13. FRESHWATER FISHING SPORTSMEN ARE REMINDED TO: General Information.............................................13 • Clean out truck beds and refrain from throwing Freshwater State Creel & Size Limits....................16 cigarette butts or other trash out of the car or watercraft. 18. SALTWATER FISHING • Carry a trash bag in your car or boat. General Information.............................................18 • Securely cover trash containers to prevent Saltwater State Creel & Size Limits.......................21 animals from spreading litter. 26. OTHER RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES Call the state’s “Litterbug Hotline” to report any Recreational Shrimping........................................26 potential littering violations including dumpsites Recreational Oystering.........................................27 and littering in public. Those convicted of littering Recreational Crabbing..........................................28 Recreational Crawfishing......................................29 face hefty fines and litter abatement work. -

FOIR-Coongie-Road-Survey-Project

COONGIE ROAD BIRDS, MAMMALS & VEGETATION SURVEY 2014 A project undertaken by the Friends of the Innamincka Reserves Dune near Coongie Road, Innamincka Regional Reserve i REPORT ON THE COONGIE ROAD BIRDS, MAMMALS & VEGETATION SURVEY 2014 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 A. Project coordinator and field team 1 B. Background 1 C. Approach 2 D. Objectives 2 E. Programme of research 2 METHODS 3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 6 A. Bird survey data 6 B. Habitats 9 C. Flora 11 D. Mammals 13 E. Reptiles and amphibians 15 F. Threats and potential impacting factors 15 G. Archeological sites 18 CONCLUSIONS 19 APPENDIX I - Location of Census Stops 20 APPENDIX II - Transect Bird Data 23 APPENDIX III - Photographic and Habitat Records 27 APPENDIX IV - Using a GPS to Navigate a Transect 49 ii REPORT ON THE COONGIE ROAD BIRDS, MAMMALS & VEGETATION SURVEY 2014 INTRODUCTION A. PROJECT COORDINATOR AND FIELD TEAM Coordinator: Kate Buckley Team Leaders: Euan Moore, Jenny Rolland, Rose Treilibs, Vern Treilibs Field Team: Daphne Hards, Sonja Ross, Karen and Geoff Russell, Jen and Len Kenna, Barbara and Peter Bansemer, Fae and Jim Trueman, Jan and Ray Hutchinson In 2014 this project was carried out as a volunteer activity by members of the Friends of Innamincka Reserves (FOIR). There was no external funding for the project. B. BACKGROUND The Coongie Road extends from Innamincka north- west to Malkumba-Coongie Lakes NP via Kudriemitchie. It passes through a range of habitat types from dry grasslands to wetlands. While average rainfall is low (177 mm per annum), the Innamincka area is in a region of maximum rainfall variability for Australia.