IDL-11669.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9N1.5 Determine the Square Root of Positive Rational Numbers That Are Perfect Squares

9N1.5 Determine the square root of positive rational numbers that are perfect squares. Square Roots and Perfect Squares The square root of a given number is a value that when multiplied by itself results in the given number. For example, the square root of 9 is 3 because 3 × 3 = 9 . Example Use a diagram to determine the square root of 121. Solution Step 1 Draw a square with an area of 121 units. Step 2 Count the number of units along one side of the square. √121 = 11 units √121 = 11 units The square root of 121 is 11. This can also be written as √121 = 11. A number that has a whole number as its square root is called a perfect square. Perfect squares have the unique characteristic of having an odd number of factors. Example Given the numbers 81, 24, 102, 144, identify the perfect squares by ordering their factors from smallest to largest. Solution The square root of each perfect square is bolded. Factors of 81: 1, 3, 9, 27, 81 Since there are an odd number of factors, 81 is a perfect square. Factors of 24: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 Since there are an even number of factors, 24 is not a perfect square. Factors of 102: 1, 2, 3, 6, 17, 34, 51, 102 Since there are an even number of factors, 102 is not a perfect square. Factors of 144: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 16, 18, 24, 36, 48, 72, 144 Since there are an odd number of factors, 144 is a perfect square. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Hertz So Good: Amazon, General Jurisdiction's Principal Place of Business, and Contacts Plus As the Future of the Exceptional Case D

Cornell Law Review Volume 104 Article 7 Issue 4 May 2019 Hertz So Good: Amazon, General Jurisdiction's Principal Place of Business, and Contacts Plus as the Future of the Exceptional Case D. (Douglas) E. Wagner Cornell Law School, J.D. 2019, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Commercial Law Commons, and the Jurisdiction Commons Recommended Citation D. (Douglas) E. Wagner, Hertz So Good: Amazon, General Jurisdiction's Principal Place of Business, and Contacts Plus as the Future of the Exceptional Case, 104 Cornell L. Rev. 1085 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol104/iss4/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE HERTZ SO GOOD: AMAZON, GENERAL JURISDICTION'S PRINCIPAL PLACE OF BUSINESS, AND CONTACTS PLUS AS THE FUTURE OF THE EXCEPTIONAL CASE D.E. Wagnert INTRODUCTION ....................................... 1086 I. THE GENESIS OF GENERAL JURISDICTION ............ 1092 A. InternationalShoe Eventually Leads to General and Specific Jurisdiction .................... 1093 B. Doing Business: General Jurisdiction Before Goodyear and Daimler . ................... 1096 C. Goodyear and Daimler. Specific Jurisdiction Comes of Age and General Jurisdiction Limited to Two (or Three) Circumstances ............. 1098 D. Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor Split Over General Jurisdiction . ..................... 1099 II. BRISTOL-MYERS SQuIBB's RESTRICTION OF SPECIFIC JURISDICTION CREATES NEW IMPORTANCE FOR GENERAL JURISDICTION ........................ 1104 III. -

Grade 7/8 Math Circles the Scale of Numbers Introduction

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 7/8 Math Circles November 21/22/23, 2017 The Scale of Numbers Introduction Last week we quickly took a look at scientific notation, which is one way we can write down really big numbers. We can also use scientific notation to write very small numbers. 1 × 103 = 1; 000 1 × 102 = 100 1 × 101 = 10 1 × 100 = 1 1 × 10−1 = 0:1 1 × 10−2 = 0:01 1 × 10−3 = 0:001 As you can see above, every time the value of the exponent decreases, the number gets smaller by a factor of 10. This pattern continues even into negative exponent values! Another way of picturing negative exponents is as a division by a positive exponent. 1 10−6 = = 0:000001 106 In this lesson we will be looking at some famous, interesting, or important small numbers, and begin slowly working our way up to the biggest numbers ever used in mathematics! Obviously we can come up with any arbitrary number that is either extremely small or extremely large, but the purpose of this lesson is to only look at numbers with some kind of mathematical or scientific significance. 1 Extremely Small Numbers 1. Zero • Zero or `0' is the number that represents nothingness. It is the number with the smallest magnitude. • Zero only began being used as a number around the year 500. Before this, ancient mathematicians struggled with the concept of `nothing' being `something'. 2. Planck's Constant This is the smallest number that we will be looking at today other than zero. -

Channel Lineup 3

International 469 ART (Arabic) MiVisión 818 Ecuavisa International 476 ITV Gold (South Asian) 780 FXX 821 Music Choice Pop Latino 477 TV Asia (South Asian) 781 FOX Deportes 822 Music Choice Mexicana 478 Zee TV (South Asian) 784 De Película Clasico 823 Music Choice Musica 479 Aapka COLORS 785 De Película Urbana 483 EROS NOW On Demand 786 Cine Mexicano 824 Music Choice Tropicales 485 itvn (Polish) 787 Cine Latino 825 Discovery Familia 486 TVN24 (Polish) 788 TR3s 826 Sorpresa 488 CCTV- 4 (Chinese) 789 Bandamax 827 Ultra Familia 489 CTI-Zhong Tian (Chinese) 790 Telehit 828 Disney XD en Español 497 MBC (Korean) 791 Ritmoson Latino 829 Boomerang en Español 498 TVK (Korean) 792 Latele Novela 830 Semillitas 504 TV JAPAN 793 FOX Life 831 Tele El Salvador 507 Rai Italia (Italian) 794 NBC Universo 832 TV Dominicana 515 TV5MONDE (French) 795 Discovery en Español 833 Pasiones 521 ANTENNA Satellite (Greek) 796 TV Chile MiVisión Plus 522 MEGA Cosmos (Greek) 797 TV Espanola Includes ALL MiVisión Lite 528 Channel One Russia 798 CNN en Español channels PLUS (Russian) 799 Nat Geo Mundo 805 ESPN Deportes 529 RTN (Russian) 800 History en Español 808 beIN SPORTS Español 530 RTVI (Russian) 801 Univision 820 Gran Cine 532 NTV America (Russian) 802 Telemundo 834 Viendo Movies 535 TFC (Filipino) 803 UniMas 536 GMA Pinoy TV (Filipino) 806 FOX Deportes 537 GMA Life TV (Filipino) 809 TBN Enlace 538 Myx TV (Pan Asian) 810 EWTN en Español 539 Filipino On Demand 813 CentroAmérica TV 540 RTPi (Portuguese) 815 WAPA America 541 TV Globo (Portuguese) 816 Telemicro Internacional 542 PFC (Portuguese) 817 Caracol TV = Available on RCN On Demand RCN On Demand With RCN On Demand get unlimited access to thousands of hours of popular content whenever you want - included FREE* with your Streaming TV subscription! We’ve added 5x the capacity to RCN On Demand, so you never have to miss a moment. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Representing Square Numbers Copyright © 2009 Nelson Education Ltd

Representing Square 1.1 Numbers Student book page 4 You will need Use materials to represent square numbers. • counters A. Calculate the number of counters in this square array. ϭ • a calculator number of number of number of counters counters in counters in in a row a column the array 25 is called a square number because you can arrange 25 counters into a 5-by-5 square. B. Use counters and the grid below to make square arrays. Complete the table. Number of counters in: Each row or column Square array 525 4 9 4 1 Is the number of counters in each square array a square number? How do you know? 8 Lesson 1.1: Representing Square Numbers Copyright © 2009 Nelson Education Ltd. NNEL-MATANSWER-08-0702-001-L01.inddEL-MATANSWER-08-0702-001-L01.indd 8 99/15/08/15/08 55:06:27:06:27 PPMM C. What is the area of the shaded square on the grid? Area ϭ s ϫ s s units ϫ units square units s When you multiply a whole number by itself, the result is a square number. Is 6 a whole number? So, is 36 a square number? D. Determine whether 49 is a square number. Sketch a square with a side length of 7 units. Area ϭ units ϫ units square units Is 49 the product of a whole number multiplied by itself? So, is 49 a square number? The “square” of a number is that number times itself. For example, the square of 8 is 8 ϫ 8 ϭ . -

International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding Construction of Reality in Post-Disaster News on Televis

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 6, Issue 3 and Multireligious Understanding June, 2019 Pages: 845-853 Construction of Reality in Post-Disaster News on Television Programs: Analysis of Framing in "Sulteng Bangkit" News Program on TVRI Arif Pujo Suroko; Widodo Muktiyo; Andre Novie Rahmanto Department of Communication Science, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia , Universita http://dx.doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v6i3.876 Abstract Television is a mass media which has always been a top priority for the community in getting accurate and reliable information. The presence of television will always be awaited by the public to convey all information, especially when natural disasters occur in an area. This article tries to provide an analysis of the news program produced by the TVRI Public Broadcasting Institutions. This study uses the framing analysis method, with a four-dimensional structural approach to the news text as a framing device from Zhongdang Pan and Gerald M. Kosicki. This analysis aims to understand and then describe how reality is constructed by TVRI broadcasting institutions in the frame of television news programs on natural disasters, earthquakes and sunbaths in Central Sulawesi. The results of the analysis with framing showed that TVRI's reporting through the special program of natural disaster recovery "Sulteng Bangkit" showed prominence on the government's role in the process of handling and restoring conditions after the earthquake and tsunami natural disaster in Central Sulawesi. Keywords: Reality Construction; TV Programs; Media Framing; Natural Disasters 1. -

Senderliste-Digital-Tv.Pdf

Zusatz-Pakete Alle Preise pro Monat. Premium CHF 33.– Entertainment CHF 22.– Sports CHF 11.– 2 Monate1) gratis Im Premium-Paket erhalten Sie alles in einem: Plus, Entertainment, Sports und den Erotik-Sender Blue Hustler. 188 Nicktoons 271 Eurosport 1 HD 189 Cartoon Netw. HD d/e 272 Eurosport 2 HD 190 Boomerang HD d/e 274 sport1+ HD 194 Fix & Foxi 275 sportdigital HD CHF 5.– Plus 197 Nick Jr. 278 Auto Motor & Sport HD 201 Animal Planet HD 279 Motors TV HD d/f/e Deutschsprachige Sender Weitere Sprachen 202 Nat Geo Wild HD d/e 282 sport 1 US HD e 100 RTL HD 448 Extremadura SAT spa 203 Nat Geo HD d/e 285 Extreme Sports Channel d/f/e 101 SAT.1 HD 494 CT24 Czech News cze 204 Discovery HD 286 Fast&FunBox HD e 102 ProSieben HD 497 Duna TV HD hun PLANET 205 HD Planet HD 287 FightBox HD e 103 VOX HD 498 TVRi Romania Int. rum 206 GEO Television HD d/e 290 Nautical Channel HD e/f 104 RTL 2 HD 501 Slovenija 1 slv 212 Travel Channel HD d/e 105 kabel eins HD 508 Z1 TV Sljeme hrv 219 History HD d/e 107 RTLNITRO HD 509 DM Sat srp 221 A&E d/e 108 n-tv HD 521 RTRS plus bos Adult CHF 24.– 227 Bon Gusto HD 111 Super RTL HD 522 OBN bos 295 Penthouse HD 230 E! Entertainment HD d/e 113 sixx HD 529 RTCG TV Montenegro mon 296 Blue Hustler2) 232 RTL Living HD 124 Anixe HD Serie 536 TVSH Shqiptar alb 297 Hustler TV 233 RTL Passion HD 133 Welt der Wunder 551 TRT 1 HD tur 298 Private TV 236 Romance TV HD 163 Gute Laune TV 557 Kanal D (Euro D) tur 237 Universal Channel HD d/e Sender mit 7 Tage Replay-Funktion auf Verte! TV. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JOHN RATIGAN Interviewed by: Ray Ewing Initial interview date: August 17, 2007 Copyright 2008 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in New York, raised in Minnesota Dartmouth College Yale law school Marriage Entered the Foreign Service in 1973 Peace Corps, Tanzania, Teacher 19-.- Training, Colum0ia Teachers College Tanzania economy Environment Class-work Chinese 1elations with 2S Em0assy Denver, Colorado, 3aw practice -1973 Teheran, Iran, Consular Officer 1973-1975 Immigrant visa cases Security Oil economy Assassination attempts Family Student visas Am0assador 1ichard Helms State Department, Operations Center 1975-197- State Department, 6reek Desk Officer 197--1978 Forged ca0le incident 6reek-Americans 6reek Em0assy 1elations 1 State Department, FSI9 Political-Economic study 1978 Singapore, 6eneral Officer 1979-1982 Am0assador 1ichard :neip Staff Congressional visits Environment Consular operations 1efugees Strict law enforcement ASEA conferences State Department, FSI9 Ara0ic language training 1982 Cairo, Egypt, Consul 6eneral 1982-198. Environment Em0assy compound Visa pro0lems 2S Am0assadors American tourists Washington, D.C., Pearson Fellow for Senator Pearson 198.-1985 Senate Immigration Su0committee California growers> influence Proposed legislation killed Fraudulent visa cases Visa Waiver Pilot Program I S/State relations Pearson program Congress/State relationship State Department, Bureau of 1efugee Affairs 1985-1987 Monitoring expenditures -

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2012-86

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2012-86 PDF version Ottawa, 10 February 2012 Revised list of non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution – Annual compilation of amendments 1. In Broadcasting Public Notice 2006-55, the Commission announced that it would periodically issue public notices setting out revised lists of eligible satellite services that include references to all amendments that have been made since the previous public notice setting out the lists was issued. 2. In Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2011-399, the Commission replaced the lists of eligible satellite services with a simplified, consolidated list known as the List of non- Canadian programming services authorized for distribution (the list). This new list came into effect 1 September 2011. 3. Accordingly, in Appendix 1 to this regulatory policy, the Commission sets out all amendments made to the list since the issuance of Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2011-43. In addition, the non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution that were approved up to and including 23 January 2012 are set out in Appendix 2. 4. The Commission notes that, as set out in Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2011-226, CBS College Sports Network was renamed CBS Sports Network. This name change is reflected in Appendix 2. Secretary General Related documents • List of non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution, Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2011-399, 30 June 2011 • Renaming of CBS College Sports Network as CBS Sports Network on the lists of -

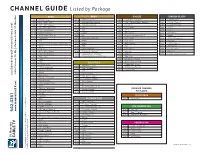

CHANNEL GUIDE Listed by Package

Listed by Package CHANNEL GUIDE BASIC BASIC BRONZE SPANISH SILVER* 104 WGN-Chicago 267 Lifetime Television 142 Fox Business Network 400 Fox Deportes 106 PBS - WPBT-Miami 269 Lifetime Movie Network 152 JNN - Jamaica News Network 402 CNN en Espanol 108 NBC - WTVJ-Miami 273 TV Guide Network 155 EuroNews 404 E! Latin America 110 CW - WPIX-New York 274 TNT 156 CCTV News 406 GLITZ 112 FOX - WSVN-Miami 276 TBS 182 JCTV 410 HTV 114 Bulletin Channel 278 Space 186 Vh1 Classic 411 MuchMusic 115 TV15 - SXM Cable TV 280 BET 190 Reggae Entertainment TV 412 Infinito 116 CaribVision 297 Game Show Network 195 BET Gospel 414 Caracol Television 119 RFO 309 EWTN 208 Fight Now! 416 Pasiones 120 Special Events Channel - SXM Cable TV 311 3ABN 217 Golf Channel 419 EWTN Espanol 121 3SCS 314 TBN 219 TVG 421 TBN Enlace 122 BVN TV 337 DWTV (German) 238 Fashion TV 424 Disney Junior 126 ABC - WPLG-Miami 418 Azteca International 245 Halogen 428 Baby TV 127 CBS - WFOR-Miami 900 - Galaxie Music Channels* 246 Baby TV 430 La Familia Cosmovision (refer to channel category for listing) 130 TeleCuraco 949 256 Teen Nick 136 CNBC 290 Sundance Channel 138 CNN SOLID GOLD 316 The Church Channel 146 Headline News 324 France 24 (French) 123 WWOR-New York 148 CNN International 325 TV5 Monde (French) 150 One Caribbean TV 151 Weather Channel 332 EuroChannel 177 A&E 153 MSNBC 184 MTV Hits USA 157 BBC World 192 CMT Pure Country 160 France 24 (English) 204 Fox Soccer Channel 162 Animal Planet 282 Africa Channel 166 Lifetime Real Women 284 G4 .net 168 TruTV X 286 Sony Entertainment TV 175 National Geographic PREMIUM CHANNEL 292 Warner Channel 179 Discovery Channel PACKAGES 313 Smile of a Child 191 Tempo SPORTSMAX 194 CENTRIC 196 MTV PLATINUM PLUS 200 SportsMax 206 Big Ten Network 131 CBC - Canada innovativeS 209 ESPN Caribbean 140 Fox News Channel w.