Novels for Students, Volume 31 – Finals/ 1/27/2010 12:35 Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fame Attack : the Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences

Rojek, Chris. "The Icarus Complex." Fame Attack: The Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 142–160. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849661386.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:03 UTC. Copyright © Chris Rojek 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 The Icarus Complex he myth of Icarus is the most powerful Ancient Greek parable of hubris. In a bid to escape exile in Crete, Icarus uses wings made from wax and feathers made by his father, the Athenian master craftsman Daedalus. But the sin of hubris causes him to pay no heed to his father’s warnings. He fl ies too close to the sun, so burning his wings, and falls into the Tsea and drowns. The parable is often used to highlight the perils of pride and the reckless, impulsive behaviour that it fosters. The frontier nature of celebrity culture perpetuates and enlarges narcissistic characteristics in stars and stargazers. Impulsive behaviour and recklessness are commonplace. They fi gure prominently in the entertainment pages and gossip columns of newspapers and magazines, prompting commentators to conjecture about the contagious effects of celebrity culture upon personal health and the social fabric. Do celebrities sometimes get too big for their boots and get involved in social and political issues that are beyond their competence? Can one posit an Icarus complex in some types of celebrity behaviour? This chapter addresses these questions by examining celanthropy and its discontents (notably Madonna’s controversial adoption of two Malawi children); celebrity health advice (Tom Cruise and Scientology); and celebrity pranks (the Sachsgate phone calls involving Russell Brand and Jonathan Ross). -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Fawlty Towers - Episode Guide

Performances October 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15 Three episodes of the classic TV series are brought to life on stage. Written by John Cleese & Connie Booth. Music by Dennis Wilson By Special Arrangement With Samuel French and Origin Theatrical Auditions Saturday June 18, Sunday June 19 Thurgoona Community Centre 10 Kosciuszko Road, Thurgoona NSW 2640 Director: Alex 0410 933 582 FAWLTY TOWERS - EPISODE GUIDE ACT ONE – THE GERMANS Sybil is in hospital for her ingrowing toenail. “Perhaps they'll have it mounted for me,” mutters Basil as he tries to cope during her absence. The fire-drill ends in chaos with Basil knocked out by the moose’s head in the lobby. The deranged host then encounters the Germans and tells them the “truth” about their Fatherland… ACT TWO – COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS It’s not a wise man who entrusts his furtive winnings on the horses to an absent-minded geriatric Major, but Basil was never known for that quality. Parting with those ill-gotten gains was Basil’s first mistake; his second was to tangle with the intermittently deaf Mrs Richards. ACT THREE – WALDORF SALAD Mine host's penny-pinching catches up with him as an American guest demands the quality of service not normally associated with the “Torquay Riviera”, as Basil calls his neck of the woods. A Waldorf Salad is not part of Fawlty Towers' standard culinary repertoire, nor is a Screwdriver to be found on the hotel's drinks list… FAWLTY TOWERS – THE REGULARS BASIL FAWLTY (John Cleese) The hotel manager from hell, Basil seems convinced that Fawlty Towers would be a top-rate establishment, if only he didn't have to bother with the guests. -

Slash Album Download Slash Feat

slash album downloaD Slash feat. Myles Kennedy & The Conspirators discography. 1. The Call Of The Wild 2. Halo 3. Standing In The Sun 4. Ghost 5. Back From Cali 6. My Antidote 7. Serve You Right 8. Boulevard Of Broken Hearts 9. Shadow Life 10. We're All Gonna Die 11. Doctor Alibi 12. Lost Inside The Girl 13. Wicked Stone. Sahara. Slash & Koshi Inaba From the album Slash Released: November 2009 Label: Universal Tracklist: 1. Sahara / 2. Paradise City (feat. Cypress Hill & Fergie) By The Sword. Ghost (promo) Slash, Ian Astbury & Izzy Stradlin From the album Slash Released: June 2010 Label: Roadrunner Tracklist: 1. Ghost. Back From Cali. Beautiful Dangerous. iTunes Session. Slash & Myles Kennedy Studio songs recorded exclusively for iTunes Released: December 2010 Label: iTunes Store Tracklist: 1. Back From Cali / 2. Communication Breakdown / 3. Fall To Pieces / 4. Rocket Queen / 5. Starlight / 6. Sucker Train Blues. Starlight (promo) Slash & Myles Kennedy From the album Slash Released: July 2011 Label: Roadrunner Tracklist: 1. Starlight. You're A Lie. Standing In The Sun. Slash, Myles Kennedy & The Conspirators From the album Apocalyptic Love Released: June 2012 Label: Roadrunner Tracklist: 1. Standing In The Sun. Download Slash - Live at the Roxy 25.09.14 (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) (2015) Album. 1. Ghost (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) 2. 30 Years to Life (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) 3. Rocket Queen (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) 4. Bent to Fly (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) 5. Starlight (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) 6. You're a Lie (feat. Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators) 7. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay from Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement

A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay From Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement Simon Dor Université de Montréal It is quite usual in strategy games to claim that strategies have a history of their own, chess being the canonical example (Murray 2002). The common strategies of a certain game change over time—often called the “metagame”— and can be retraced from a historical perspective. StarCraft II’s (Blizzard Entertainment, 2010-) community goes as far as to write histories of specific matchups (Alejandrisha et al. 2012), but every strategy game in some regards opens a space where gameplay can evolve. A 2009 walkthrough of the 1994 game Warcraft: Orcs and Humans (Blizzard Entertainment) states that the “reason most people think this game is so hard, is because they try to play it like an RTS [Real-Time Strategy game]” (Boehmer 2009, §2.03). It is quite surprising today to read this claim, considering Warcraft is widely regarded as one of the pioneers in the RTS genre, alongside with its Westwood’s earlier counterpart, Dune II: The Building of A Dynasty (Westwood Studios, 1992). In the perspective of mapping a history of the RTS genre, this kind of statement is quite problematic. Playing a RTS in 2009 is not like what was playing a strategy game in 1994, but how can we as researchers take into account a historical distance in playing habits? Warcraft’s difficulty was probably raised retrospectively, since playing habits acquired in subsequent games induce certain types of actions that do not necessarily favor victory in earlier releases. -

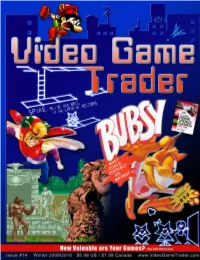

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Green Anarchy

GREENGREEN ANARCHYANARCHY AnAn Anti-CivilizationAnti-Civilization JournalJournal ofof TheoryTheory andand ActionAction www.greenanarchy.org SPRING/ SUMMER 2008 we live to live ISSUE #25 (i guess you could say we are “pro-lifers”) GREEN ANARCHY PO BOX 11331 Eugene, OR 97440 [email protected] $4 USA, $6 CANADA, $7 EUROPE, $8 WORLD FREE TO U.S.PRISONERS Direct Action Anarchist Resistance, pg 26 ContentsContents:: Ecological Defense and Animal Liberation, pg 40 Issue #25 Spring/Summer 2008 Indigenous Struggles, pg 48 Anti-Capitalist and Anti-State Battles, pg 54 Prisoner Escapes and Uprisings, pg 62 Articles Symptoms of the System’s Meltdown, pg 67 Silence byJohn Zerzan, pg 4 Straight Lines Don’t Work Any More Sections by Rebelaze, pg 6 Welcome to Green Anarchy, pg 2 Connecting to Place In the Land of the Lost: Fragment #42-44, pg 46 Questions for the Nomadic Wanderers The Garden of Peculiarities: by Sal Insieme, pg 8 State Repression News, pg 70 Hope Against Hope: Why Progressivism is as Useless Reviews, pg 74 as Leftism by Tara Specter, pg 12 News from the Balcony with Waldorf and Statler, pg 80 Sermon on the Cyber Mount Letters, pg 86 by The Honorable Reverend Black A. Hole,pg 14 Subscriber and Distributor Info, pg 90 Second-Best Life: Real Virtuality Green Anarchy Distro, pg 90 byJohn Zerzan, pg 16 Announcements, pg 92 Canaries In the Clockwork by earth-ling-gerring, pg 17 A Specious Species by C.E. Hayes, pg 18 Alone Together: the City and its Inmates .. .. .. inin thethe midstmidst ofof activity,activity, by John Zerzan, pg 20 therethere is a blurring between The End Of Slavery: Urban Scout On Creating A World thethe solosolo and the swarm. -

Poor Unfortunate Souls)

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 SYNOPSIS 2 CASTING 4 MUSIC DIRECTION 8 DIRECTING TIPS 17 DESIGN 20 BEYOND THE STAGE 35 RESOURCES 44 CREDITS 48 Betcha on land They understand Bet they don’t reprimand their daughters Bright young women Sick of swimmin’ Ready to stand — “Part of Your World,” lyrics by Howard Ashman INTRODUCTION hether you first came toThe Little Mermaid by searching for his place in the world. As Ariel and Eric way of the original Hans Christian Andersen learn to make decisions for themselves, King Triton tale, the classic Disney animated film, or the stage and Grimsby learn the parental lesson of letting go. musical adaptation, the story resonates with the same emotional power. Strip the tale of its fantastical The stage adaptation of The Little Mermaid – with Betcha on land elements – mermaids and sea witches and talking music by Alan Menken, lyrics by Howard Ashman crabs – and what’s left is the simple story of a young and Glenn Slater, and book by Doug Wright – retains They understand woman struggling to come into her own. the most beloved songs and moments from the original film while deepening the core relationships There’s a little bit of Ariel in all of us: headstrong, and themes, adding in layers, textures, and songs Bet they don’t reprimand their daughters independent, insatiably curious, and longing to know to form an even more moving and relevant story. the world in all of its glory, mystery, and diversity. A This stage musical presents endless opportunities Bright young women young woman who passionately pursues her dream, for creative design – from costuming the merfolk, to Ariel makes decisions that have serious consequences, creating distinct underwater and on-land worlds, to all of which she faces with bravery and dignity. -

Suspense, Mystery, Horror and Thriller Fiction

Suspense, Mystery, Horror and Thriller Fiction September 2012 Just a Little About... Ben Sussman John Edward Andrew Peterson Steven James Linwood Barclay Elizabeth George Meet Debut Author Must Reads Joy Castro 7BefoRe suMMeR’s end CheCk out exCerpts Anthony FrAnze From the Latest by Gives us PArt vi syLvie Granotier on ‘the rules’ anthony J. Franze oF Fiction Dina rae C r e di t s John Raab From the Editor President & Chairman Suspense covers many different genres. At Shannon Raab Suspense Magazine we cover suspense/thriller/ Creative Director mystery and horror, along with all the tangent Romaine Reeves genres that come off of those four main categories. CFO The problem is defining exactly what each genre actually is. We can always take the Webster’s Starr Gardinier Reina dictionary on each, but where is the fun in that? I’ll Executive Editor try and break them down, so it will be a lot easier Terri Ann Armstrong to understand. Executive Editor Suspense is a state of mind more than an actual emotion like fear, sadness, excitement, love, etc. All J.S. Chancellor of your emotions can create a suspenseful situation, and it is those emotional elements Associate Editor that cause us to be in suspense. Will he save the girl and will they fall in love? Is the Jim Thomsen sister really dead or was she faking it? These are just some of the questions and hopefully Copy Editor answers you will find in a suspense book. A thriller has many of the same elements only the action is a little faster-paced and Contributors graphic. -

N° Artiste Titre Formatdate Modiftaille 14152 Paul Revere & the Raiders Hungry Kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben

N° Artiste Titre FormatDate modifTaille 14152 Paul Revere & The Raiders Hungry kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben Verliefd Op Jou kar 2004 48 860 14154 Paul Simon A Hazy Shade Of Winter kar 1995 18 008 14155 Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard kar 2001 41 290 14156 You Can Call Me Al kar 1997 83 142 14157 You Can Call Me Al mid 2011 24 148 14158 Paul Stookey I Dig Rock And Roll Music kar 2001 33 078 14159 The Wedding Song kar 2001 24 169 14160 Paul Weller Remember How We Started kar 2000 33 912 14161 Paul Young Come Back And Stay kar 2001 51 343 14162 Every Time You Go Away mid 2011 48 081 14163 Everytime You Go Away (2) kar 1998 50 169 14164 Everytime You Go Away kar 1996 41 586 14165 Hope In A Hopeless World kar 1998 60 548 14166 Love Is In The Air kar 1996 49 410 14167 What Becomes Of The Broken Hearted kar 2001 37 672 14168 Wherever I Lay My Hat (That's My Home) kar 1999 40 481 14169 Paula Abdul Blowing Kisses In The Wind kar 2011 46 676 14170 Blowing Kisses In The Wind mid 2011 42 329 14171 Forever Your Girl mid 2011 30 756 14172 Opposites Attract mid 2011 64 682 14173 Rush Rush mid 2011 26 932 14174 Straight Up kar 1994 21 499 14175 Straight Up mid 2011 17 641 14176 Vibeology mid 2011 86 966 14177 Paula Cole Where Have All The Cowboys Gone kar 1998 50 961 14178 Pavarotti Carreras Domingo You'll Never Walk Alone kar 2000 18 439 14179 PD3 Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is kar 1998 45 496 14180 Peaches Presidents Of The USA kar 2001 33 268 14181 Pearl Jam Alive mid 2007 71 994 14182 Animal mid 2007 17 607 14183 Better -

Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, Non-Member; $1.35, Member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; V15 N1 Entire Issue October 1972

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 091 691 CS 201 266 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Science Fiction in the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Oct 72 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROMKen Donelson, Ed., Arizona English Bulletin, English Dept., Ariz. State Univ., Tempe, Ariz. 85281 ($1.50); National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, non-member; $1.35, member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v15 n1 Entire Issue October 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Booklists; Class Activities; *English Instruction; *Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; Reading Materials; *Science Fiction; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Heinlein (Robert) ABSTRACT This volume contains suggestions, reading lists, and instructional materials designed for the classroom teacher planning a unit or course on science fiction. Topics covered include "The Study of Science Fiction: Is 'Future' Worth the Time?" "Yesterday and Tomorrow: A Study of the Utopian and Dystopian Vision," "Shaping Tomorrow, Today--A Rationale for the Teaching of Science Fiction," "Personalized Playmaking: A Contribution of Television to the Classroom," "Science Fiction Selection for Jr. High," "The Possible Gods: Religion in Science Fiction," "Science Fiction for Fun and Profit," "The Sexual Politics of Robert A. Heinlein," "Short Films and Science Fiction," "Of What Use: Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "Science Fiction and Films about the Future," "Three Monthly Escapes," "The Science Fiction Film," "Sociology in Adolescent Science Fiction," "Using Old Radio Programs to Teach Science Fiction," "'What's a Heaven for ?' or; Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "A Sampler of Science Fiction for Junior High," "Popular Literature: Matrix of Science Fiction," and "Out in Third Field with Robert A.