Henna Karppinen-Kummunmäki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2004 Front

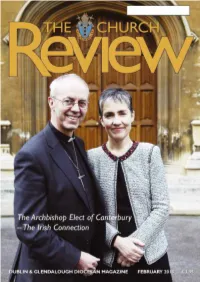

LENT 2013 COUNT YOUR BLESSINGS Give thanks and celebrate the good things in your life this Lent with our thought-provoking Count Your Blessings calendar enclosed in this edition of the Review. Each day from Ash Wednesday to Easter Sunday, forty bite-sized reflections will inspire you to give thanks for the blessings in your life, and enable you to step out in prayer and action to help FKDQJH WKH OLYHV RI WKH ZRUOG·V SRRUHVW communities. To order more copies please ring 611 0801 or write to us at: Christian Aid, 17 Clanwilliam Terrace Dublin 2 8 9 9 6 Y H C www.christianaid.ie CHURCH OF IRE LAND UNITE D DIOCE S ES CHURCH REVIEW OF DUB LIN AND GLE NDALOUGH ISSN 0790-0384 The Most Reverend Michael Jackson, Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Glendalough, Church Review is published monthly Primate of Ireland and Metropolitan. and usually available by the first Sunday. Please order your copy from your Parish by annual sub scription. €40 for 2013 AD. POSTAL SUBSCRIIPTIIONS//CIIRCULATIION Archbishop’s Lette r Copies by post are available from: Charlotte O’Brien, ‘Mountview’, The Paddock, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow. E: [email protected] T: 086 026 5522. FEBRUARY 2013 The cost is the subscription and appropriate postage. I was struck early in the New Year, while leafing through a newspaper, to find the following statement: Happiness and vulnerability are often the same thing. It was not a religious paper and in COPY DEADLIINE no way did the sentiment it voiced set out to be theological. However, it got me thinking, as often All editorial material MUST be with the I find to be the case with certain things which say something from their own context into another Editor by 15th of the preceeding and quite different context, about something important to me. -

National University of Ireland Maynooth

National University Of Ireland Maynooth THE REDECORATION AND ALTERATION OF CASTLETOWN HOUSE BY LADY LOUISA CONOLLY 1759-76 by GILLIAN BYRNE THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF M. A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY ST PATRICK’S COLLEGE MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R.V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr J. Hill August 1997 Contents Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter one; The Conolly family and the early history of Castletown House 10 Chapter two; The alterations made to Castletown House 1759-76 32 Chapter three; Lady Louisa Conolly ( 1743-1821 ) mistress of Castletown 87 Conclusion 111 Appendix 1 - Glossary of architectural terms and others ! 13 Appendix 2 - Castletown House 1965 to 1997 1 i 6 ii Page Bibliography 118 Illustrations Fig. 1 Aerial view of Castletown House. 2 Fig. 2 View of the north facade. 6 Fig. 3 View of the facade from the south-east. 9 Fig. 4 Speaker William Conolly by Charles Jervas. 11 Fig. 5 Katherine Conolly with a niece by Charles Jervas. 12 Fig. 6 The obelisk and the wonderful bam. 13 Fig. 7 View of the central block of Castletown. 15 Fig. 8 Plans by Galilei which may relate to Castletown. 16 Fig. 9 View of the west colonnade and wing. 17 Fig.10 Exterior and interior views of the east wing. 20 Fig. 11 Plan of the ground floor. 21 Fig.12 Ground floor plan by Edward Lovett Pearce. 22 Fig.13 View of Castletown from the south west. 25 Fig.14 Tom and Lady Louisa Conolly, portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds. 26 Fig.15 Portraits of Lady Emily Lennox and James, earl of Kildare. -

Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740 - 1832 Pdf

FREE ARISTOCRATS: CAROLINE, EMILY, LOUISA AND SARAH LENNOX 1740 - 1832 PDF Stella Tillyard | 480 pages | 14 Mar 1995 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099477112 | English | London, United Kingdom Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox, by Stella Tillyard She was the third of the famous Lennox Sistersand was notable among them for leading a wholly uncontroversial life filled with good works. Louisa Aristocrats: Caroline still Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740 - 1832 child when her parents died within a year of Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740 - 1832 other in and Her husband, a wealthy land-owner and keen horseman, was also a successful politician who was elected to Parliament as early as The couple lived in the Palladian mansion Castletown House in County Kildarethe decoration of which she directed throughout the s and s. Emily hydroelectric power station was constructed on the site of 'Cliff House' and was commissioned in Themselves unhappily childless, at that point they took up the welfare of young children from disadvantaged backgrounds as a lifelong project, contributing both money and effort towards initiatives which would enable foundlings and vagabonds to acquire productive skills and support themselves. They developed one of the first Industrial Schools where boys learnt trades, and Lady Louisa took active personal interest in Emily the students. Emily, who would spend long months with her aunt in Kildare, married Sir Henry Bunbury, 7th Baronetand moved to Suffolkalthough she remained close to her aunt until her death. Thomas Conolly died in Upon his death, the major part of his estates, which included Wentworth Castlepassed to a distant relative, Frederick Vernon. -

July Online-Proof.Pub

22 Portrait of Lady Emily Mary Lennox Maynooth Castle Keep Art Group Update Duchess of Leinster The Maynooth Castle Keep Art Group is taking its usual summer break. A portrait of Lady Emily Mary Lennox by Joshua Reynolds 1723-1792) was Now I know our followers and supporters will be thinking that we have been brought by the OPW in 2019 and is on display in Castletown House, which on a break for the last year as we have had not been able to have our Annual was the home of Emily’s sister, Lady Louisa Conolly. Art Exhibition. But we were not deterred, and in our efforts to keep in touch and to keep painting we have been having weekly zoom art meetings. Emilia Mary was born on 6 October 1731, the second of the seven surviving children of Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond and Lennox and Sarah, In the beginning these took the form of members of the group giving daughter of William Cadogan, Earl Cadogan. Lady Emily Lennox, as she was demonstrations to the rest of us, then we mixed this with sourced free known, was also a god-daughter of George II. She spent her early years at tutorials on Youtube and eventually we met and did our own work for an Goodwood House in Sussex. hour and a half each week. The results were surprising. Giving demonstrations to the group e.g. how to paint waves, clouds, dealing with Lady Emily was married at the age of 15, to James Fitzgerald, Earl of light and shade, still life, landscapes, composition and perspective was a great Kildare. -

Female Architectural Patronage in Eighteenth-Century Britain

Maids, Wives and Widows: Female Architectural Patronage in Eighteenth-Century Britain Amy Lynn Boyington This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge Department of Architecture August 2017 Abstract Maids, Wives and Widows: Female Architectural Patronage in Eighteenth- Century Britain Amy Lynn Boyington This thesis explores the extent to which elite women of the eighteenth century commissioned architectural works and the extent to which the type and scale of their projects was dictated by their marital status. Traditionally, architectural historians have advocated that eighteenth-century architecture was purely the pursuit of men. Women, of course, were not absent during this period, but their involvement with architecture has been largely obscured and largely overlooked. This doctoral research has redressed this oversight through the scrutinising of known sources and the unearthing of new archival material. This thesis begins with an exploration of the legal and financial statuses of elite women, as encapsulated by the eighteenth-century marriage settlement. This encompasses brides’ portions or dowries, wives’ annuities or ‘pin-money’, widows’ dower or jointure, and provisions made for daughters and younger children. Following this, the thesis is divided into three main sections which each look at the ways in which women, depending upon their marital status, could engage in architecture. The first of these sections discusses unmarried women, where the patronage of the following patroness is examined: Anne Robinson; Lady Isabella Finch; Lady Elizabeth Hastings; Sophia Baddeley; George Anne Bellamy and Teresa Cornelys. The second section explores the patronage of married women, namely Jemima Yorke, Marchioness Grey; Amabel Hume-Campbell, Lady Polwarth; Mary Robinson, Baroness Grantham; Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough; Frances Boscawen; Elizabeth Herbert, Countess of Pembroke and Montgomery; Henrietta Knight, Baroness Luxborough and Lady Sarah Bunbury. -

Caroline Wyndham-Quin, Countess of Dunraven (1790- 1870): an Analysis of Her Discursive and Material Legacy

Caroline Wyndham-Quin, countess of Dunraven (1790- 1870): an analysis of her discursive and material legacy by Odette Clarke Thesis compiled under the supervision of Dr. B. Whelan in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of PhD University of Limerick November 2010 Declaration I confirm that the content of this thesis is my own original work except where otherwise indicated with reference to secondary sources. _____________________________ Odette Clarke November 2010 ii Abstract Caroline Wyndham was born on 24 May 1790 into the British gentry. The Wyndhams of Dunraven, whilst not being titled, were members of the land-owning and governing class in Glamorganshire, South Wales. In 1810 Caroline married Windham Quin, who belonged to an old Anglo-Irish family and who was eventually to become the second earl of Dunraven. Caroline‟s diaries, letters and annual reflections indicate that, even as a teenager, she was a deeply religious woman who had been affected by Methodism and by the evangelical revival that began in the 1780s. From the day of her eighteenth birthday in 1808 until her death in 1870 Caroline kept a diary, which forms part of her archive together with annual reflections and letters. This thesis has adopted a biographical approach in the study of this archive. An examination of Caroline‟s egodocuments has demonstrated the importance of religious discourse for the management of her, and her family‟s, emotions and her attempts to realise the prescriptive and gendered ideal state of resigned gratitude. This biographical analysis of Caroline‟s writings has also highlighted the importance of her work in the construction and preservation of a family narrative. -

Childhood: Studies in the History of Children in Eighteenth-Century Ireland

CHILDHOOD: STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF CHILDREN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY IRELAND incorporating the digital humanities project ‘IRISH CHILDREN IN 18TH CENTURY SCHOOLS AND INSTITUTIONS’ Gabrielle M. Ashford (B.A. Hons) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History St Patrick’s College Drumcondra A college of Dublin City University Supervisor of Research: Prof. James Kelly January 2012 Volume one of two Abstract The history of children and childhood in eighteenth-century Ireland has long been overlooked. Yet over the course of the century children were brought more firmly into the centre of eighteenth-century Irish society. The policies, practices and ideologies that emerged during the century provided the essential framework for a more comprehensive inclusion of children in all societal and political considerations by the nineteenth. The object of this thesis is to construct a picture of childhood among elite, gentry, peasant, pauper and institutional children over the course of the long eighteenth-century. In addition, it incorporates as a separate appendix the digital humanities project ‘Irish children in 18th century schools and institutions’. Even though childhood was a dynamic process there was a rigidity reinforced by inter- textualities and hierarchies, so that in many instances childhood remained an abstract yet distinctive process. Parental and societal attitudes shaped the expectations of children and childhood and, though all children experienced childhood, there were significantly marked differences between them based on class. This is more vividly illustrated in some aspects than others. For instance, all social classes promoted children’s health, well-being and their education, but for some it remained aspirational.