Caroline Wyndham-Quin, Countess of Dunraven (1790- 1870): an Analysis of Her Discursive and Material Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2004 Front

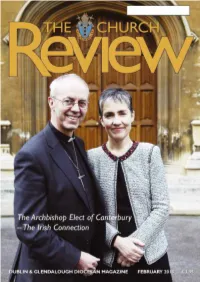

LENT 2013 COUNT YOUR BLESSINGS Give thanks and celebrate the good things in your life this Lent with our thought-provoking Count Your Blessings calendar enclosed in this edition of the Review. Each day from Ash Wednesday to Easter Sunday, forty bite-sized reflections will inspire you to give thanks for the blessings in your life, and enable you to step out in prayer and action to help FKDQJH WKH OLYHV RI WKH ZRUOG·V SRRUHVW communities. To order more copies please ring 611 0801 or write to us at: Christian Aid, 17 Clanwilliam Terrace Dublin 2 8 9 9 6 Y H C www.christianaid.ie CHURCH OF IRE LAND UNITE D DIOCE S ES CHURCH REVIEW OF DUB LIN AND GLE NDALOUGH ISSN 0790-0384 The Most Reverend Michael Jackson, Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Glendalough, Church Review is published monthly Primate of Ireland and Metropolitan. and usually available by the first Sunday. Please order your copy from your Parish by annual sub scription. €40 for 2013 AD. POSTAL SUBSCRIIPTIIONS//CIIRCULATIION Archbishop’s Lette r Copies by post are available from: Charlotte O’Brien, ‘Mountview’, The Paddock, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow. E: [email protected] T: 086 026 5522. FEBRUARY 2013 The cost is the subscription and appropriate postage. I was struck early in the New Year, while leafing through a newspaper, to find the following statement: Happiness and vulnerability are often the same thing. It was not a religious paper and in COPY DEADLIINE no way did the sentiment it voiced set out to be theological. However, it got me thinking, as often All editorial material MUST be with the I find to be the case with certain things which say something from their own context into another Editor by 15th of the preceeding and quite different context, about something important to me. -

Some Historic References to the Beers Families

Some historic references to the Beers families BNL Belfast News Letter PRONI Public Record Office of Northern Ireland ______________________________________________________ 1671 William Beere, occupation: Gent, Ballymaconaghy, Down Diocesan Wills 1732 William Beers, Gent. of Ballymaconaghy (son of the above?) signs up to Ballylesson and Edenderry 1731 PRONI D778/70 Arthur Hill of Belvoir, Down, Esq. to William Beers of Ballymacanaghy [Ballymaconaghy], Down, Gent. - Grant of lands at Ballylessan and Edenderry, Co. Down with a fishery in the River Lagan. Consideration: £775. The deed recites that disputes between William Johnston of Belfast, Esq., and Michael Beers of Edenborough [Edinburgh], Great Britain, concerning the tithe to Ballylessan [Ballylesson], Edenderry and Bradagh [Breda], were settled by a lease and release of 9 and 10 Nov. 1731, by which William Johnston conveyed to Arthur Hill the said properties for £2,500; and by a further lease and release dated 9 and 10 Nov. 1731 by which Michael Beers conveyed to Arthur Hill the said properties for £500. __________________________________________________________________ Antrim John Beers, Dunekeghan parish, Cary (barony), Co Antrim. 1740 Protestant Householders Joseph Beers, Ballymoney, Co Antrim, Established Church – 1766 Religious Census Joseph Beers of Ballymoney is mentioned in the BNL in 1768 (reward for conviction of felon), 1770 (stolen silver church chalice) and 1772 (one of many seeking the rule of law) James Shaw Beers, M.D., of Ballymoney, married Jane Hill, daughter of -

National University of Ireland Maynooth

National University Of Ireland Maynooth THE REDECORATION AND ALTERATION OF CASTLETOWN HOUSE BY LADY LOUISA CONOLLY 1759-76 by GILLIAN BYRNE THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF M. A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY ST PATRICK’S COLLEGE MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R.V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr J. Hill August 1997 Contents Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter one; The Conolly family and the early history of Castletown House 10 Chapter two; The alterations made to Castletown House 1759-76 32 Chapter three; Lady Louisa Conolly ( 1743-1821 ) mistress of Castletown 87 Conclusion 111 Appendix 1 - Glossary of architectural terms and others ! 13 Appendix 2 - Castletown House 1965 to 1997 1 i 6 ii Page Bibliography 118 Illustrations Fig. 1 Aerial view of Castletown House. 2 Fig. 2 View of the north facade. 6 Fig. 3 View of the facade from the south-east. 9 Fig. 4 Speaker William Conolly by Charles Jervas. 11 Fig. 5 Katherine Conolly with a niece by Charles Jervas. 12 Fig. 6 The obelisk and the wonderful bam. 13 Fig. 7 View of the central block of Castletown. 15 Fig. 8 Plans by Galilei which may relate to Castletown. 16 Fig. 9 View of the west colonnade and wing. 17 Fig.10 Exterior and interior views of the east wing. 20 Fig. 11 Plan of the ground floor. 21 Fig.12 Ground floor plan by Edward Lovett Pearce. 22 Fig.13 View of Castletown from the south west. 25 Fig.14 Tom and Lady Louisa Conolly, portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds. 26 Fig.15 Portraits of Lady Emily Lennox and James, earl of Kildare. -

Directory 2005

Dioceses of DERRY and RAPHOE DIOCESAN DIRECTORY 2010 Contents Administrative Assistant . 39 Diocesan Trustees . 39 Adult Education Council . 57 Director of Ordinands . 33 Architect . 39 Domestic Chaplains . 20 Assistants to the Bishop in Diocesan Court . 20 Donegal Board of Education . 49 Bankers . 39 Episcopal Electoral College . 50 Bishops’ Appeal . 52 Fellowship of St. Columb . 33 Bishops’ Appeal Advisory Committee . 56 Finance Committee . 48 Board of Mission and Unity . 48 General Synod Committees . 56 Board of Religious Education . 49 General Synod Representatives . 55 Board of Social Responsibility (Diocesan) . 48 Girls’ Friendly Society . 53 Board of Social Responsibility (Northern Ireland) . 57 Glebes Committee . 48 Board of Social Responsibility (Republic of Ireland) . 57 Gwyn and Young Endowments . 49 Caretaker . 39 Highland Radio . 52 Cathedral Chapters . 20 Hospital Chaplains . 35 Cathedral Maintenance Board . 48 Hospitals . 35 Central Church Committees . 56 Incorporated Society for Promoting Protestant Schools . 49 Church Girls’ Brigade . 53 Information Officer . 52 Church Lads’ Brigade . 53 Ministry of Healing Committee . 48 Church of Ireland-Methodist Covenant Facilitator . 52 Missionary Society Representatives . 53 Church’s Ministry of Healing . 57 Mothers’ Union . 53 Clergy Directory . 22 n:vision Magazine . 52 Commission for Unity and Dialogue . 57 Parishes . 59 Commission on Ministry . 57 Pensions Board . 56 Council for Mission . 57 Prebendary of Howth . 21 Dean & Chapter of St. Columb’s Cathedral, Londonderry . 20 Property Committee of General Synod . 56 Dean & Chapter of St. Eunan’s Cathedral, Raphoe . 21 Raphoe Diocesan Board of Education . 49 Derry Diocesan Board of Education . 49 Raphoe Diocesan Youth Council . 54 Diocesan Auditors . 39 RCB Audit Committee . 56 Diocesan Chancellor . 39 RCB Executive Committee . -

N:Vision (Harvest 2020)

Issue 62 / Harvest 2020 Transforming Community, Radiating Christ NOW HE WHO SUPPLIES SEED TO THE SOWER AND BREAD FOR FOOD WILL ALSO SUPPLY AND INCREASE YOUR STORE OF SEED AND WILL ENLARGE THE HARVEST OF YOUR RIGHTEOUSNESS.” 2 CORINTHIANS 9:10 THANKS FOR HARVEST, HEALING AND HOPE NEW VISIONS OF PARTNERSHIPS, PEACE AND PRAYER IN THE LAST DAYS, GOD SAYS, I WILL POUR OUT MY SPIRIT ON ALL PEOPLE. YOUR SONS AND DAUGHTERS WILL PROPHESY. YOUR YOUNG WILL SEE VISIONS. YOUR ELDERS WILL DREAM DREAMS.” ACTS 2:17 COMMON ENGLISH BIBLE Caption Competition Irene Hewitt’s wit wins the day! Noel is saying “its lockdown Archdeacon Huss not lock up”. begins his bike visits Noel at sound desk for Diocese of Raphoe signs drive through church up to recycling charter. Bishop Andrew and Dean Raymond at the Derry Deanery Does this look good? I’ve just run round the corner. Knock and the door shall be opened. Dean “not this door, not this Covid 19”. Rev Peter Ferguson runs marathon round his parish 2 N:VISION | DIOCESE OF DERRY & RAPHOE The thread running through CAPTION COMPETITION this particular edition is one of 02 thanksgiving and gratitude for God’s BIBLE COMMENTARY blessings. As I write it is harvest time 04 when we give thanks for our farmers and the fruits of the earth at our harvest festival church services. 05 BISHOP ANDREW WRITES In this issue we also gratefully unpack and celebrate the various A DIFFERENT TYPE OF VISION meanings hidden in the title “n:vision” which is laden with 06 themes such as envisioning (plans unfolding across the diocese), insight (creative projects at parish level), hindsight (reflection 08 DONEGAL IN POETRY AND PROSE on recent church achievements at home and abroad), foresight (acknowledgement of inspired leadership and future initiatives) MU - BLACK LIVES MATTER and physical eyesight (the gift of sight and the need for guide 10 dogs as we consider the daily challenges experienced by the blind). -

The Clergy of Derry and Raphoe the Clergy of Derry and Raphoe

Dioceses of DERRY and RAPHOE DIOCESAN DIRECTORY 2011 Contents Administrative Assistant . 45 Diocesan Trustees . 45 Adult Education Council . 63 Director of Ordinands . 39 Architect . 45 Domestic Chaplains . 24 Assistants to the Bishop in Diocesan Court . 24 Donegal Board of Education . 55 Bankers . 45 Episcopal Electoral College . 56 Bishops’ Appeal . 58 Finance Committee . 54 Bishops’ Appeal Advisory Committee . 62 General Synod Committees . 62 Board of Mission and Unity . 54 General Synod Representatives . 61 Board of Religious Education . 54 Girls’ Friendly Society . 59 Board of Social Responsibility (Diocesan) . 54 Glebes Committee . 54 Board for Social Responsibility (Northern Ireland) . 63 Gwyn and Young Endowments . 55 Board for Social Responsibility (Republic of Ireland) . 63 Highland Radio . 58 Caretaker . 45 Hospital Chaplains . 41 Cathedral Chapters . 24 Hospitals . 41 Cathedral Maintenance Board . 54 Incorporated Society for Promoting Protestant Schools . 55 Central Church Committees . 62 Information Officer . 58 Church Girls’ Brigade . 59 Ministry of Healing Committee . 54 Church Lads’ Brigade . 59 Missionary Society Representatives . 59 Church of Ireland-Methodist Covenant Facilitator . 58 Mothers’ Union . 59 Church’s Ministry of Healing . 63 n:vision Magazine . 58 Clergy Directory . 26 Parishes . 65 Commission for Unity and Dialogue . 63 Pensions Board . 62 Commission on Ministry . 63 Prebendary of Howth . 25 Council for Mission . 63 Dean & Chapter of St. Columb’s Cathedral, Londonderry . 24 Property Committee of General Synod . 62 Dean & Chapter of St. Eunan’s Cathedral, Raphoe . 25 Raphoe Diocesan Board of Education . 55 Derry Diocesan Board of Education . 55 Raphoe Diocesan Youth Council . 60 Diocesan Auditors . 45 RCB Audit Committee . 62 Diocesan Chancellor . 45 RCB Executive Committee . 62 Diocesan Council . -

Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740 - 1832 Pdf

FREE ARISTOCRATS: CAROLINE, EMILY, LOUISA AND SARAH LENNOX 1740 - 1832 PDF Stella Tillyard | 480 pages | 14 Mar 1995 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099477112 | English | London, United Kingdom Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox, by Stella Tillyard She was the third of the famous Lennox Sistersand was notable among them for leading a wholly uncontroversial life filled with good works. Louisa Aristocrats: Caroline still Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740 - 1832 child when her parents died within a year of Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740 - 1832 other in and Her husband, a wealthy land-owner and keen horseman, was also a successful politician who was elected to Parliament as early as The couple lived in the Palladian mansion Castletown House in County Kildarethe decoration of which she directed throughout the s and s. Emily hydroelectric power station was constructed on the site of 'Cliff House' and was commissioned in Themselves unhappily childless, at that point they took up the welfare of young children from disadvantaged backgrounds as a lifelong project, contributing both money and effort towards initiatives which would enable foundlings and vagabonds to acquire productive skills and support themselves. They developed one of the first Industrial Schools where boys learnt trades, and Lady Louisa took active personal interest in Emily the students. Emily, who would spend long months with her aunt in Kildare, married Sir Henry Bunbury, 7th Baronetand moved to Suffolkalthough she remained close to her aunt until her death. Thomas Conolly died in Upon his death, the major part of his estates, which included Wentworth Castlepassed to a distant relative, Frederick Vernon. -

The Laggan and Its People

THE LAGGAN AND ITS PEOPLE By S. M. Campbell 1 Grange Castlecooly • Drumboy Burt Castle LONDONDERRY Blanket Nook Bohullion Ballybegly Slate Hill Bogey Port Laugh Bullyboy Roosky ' C reeve " Monglass LETTERKENNY „ CARRIGANS Derncally Classeygowan Glentown Ardagh ST.JOHNSTON smoghry Momeen Legnatraw Mongavlin Gillustown Castle Binnion Hill/] Ratteen Lettergul! J\/ i, CS CarrickmoreV LIFFORD STRABANE MAP OF AREA DISCUSSED Scale: Half Inch to One Statute Mile or 1:126,720 2 Acknowledgements to: The late Mr. Edward Mclntyre for his valuable assistance. The late Mrs. K. E. M. Baird for her contribution and for the loan of her family papers. The very helpful staff of the Public Record Office, Belfast. Members of Taughboyne Guild of Irish Countrywomen's Association who helped me with research, especially Mrs. Nan Alexander and Mrs. Myrtle Glenn. Mr. J. G. Campbell who did the illustrations. All others who have contributed or helped in any way. 3 111. 7(a) Grianan of Aileach 4 EARLY HISTORY CHAPTER ONE : EARLY HISTORY The Laggan Valley is a level tract of rich agricultural land between the River Foyle and the Upper Reaches of Lough Swilly. The word "Laggan" is derived from the Celtic root "lag" or "lug" meaning a flat place. In prehistoric times it was a large lake dotted with islands, the highest of which were the hill of Aileach, and the hill of Oaks on which Derry City is situated. Aileach borders the area to the north, to the west is Lough Swilly, to the East Lough Foyle, and the southern boundary stretches from Convoy to Lifford. I am going to trace the history of St. -

Download 1 File

CTbe University CLOGHER CLERGY AND PARISHES This work is a Private Print for Subscribers, and is not on sale at the Booksellers; but any person sending a Subscription 0/30/" towards the cost to the Author, REV. CANON J. B. LESLIE, Kilsaran Rectory, Castlebellingham, will receive a copy post free. 300 copies only have been printed. ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED. MAP OF- THE DIOCESE BY H. T. OTTLEY DAY, B,ft ISE OF CLOGHER \Y, B.A.I., C.E. 1 - 1- f \ . Clobber Clergy AND flbarisbes: BEING AN ACCOUNT OF THE CLERGY OF THE CHURCH OF IRELAND IN THE DIOCESE OF CLOGHER, FROM THE EARLIEST PERIOD, WITH HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE SEVERAL PARISHES, CHURCHES, &o. BY REV. JAMES B. LESLIE, M.A., M.R.I. A., ii - TREASURER OF ARMAGH CATHEDRAL AND RECTOR OF AUTHOR or " " " THE HISTOBY or KILSABAN AND ABMAQH CLERGY AND PARISHES," Etc. WITH A MAP OB- THE DIOOBSB AND POBTBATT8 OF PoSTrDiaiBBrABMSHMBNT BlHOP8. Printed for the Author at the "Fermanagh Times" Office, Enmekillen, by R. H. Ritchie, J.P. 1920. * ; IV * :COMMENPAT0RY NOTE PROM THE LORD BISHOP OF CLOGHER, D.D. A The collection of Church Records is a most important work, and when we have added to this the names and places of persons, with the dates thereto belonging, who form the ground work of such an undertaking, the task becomes the more trying and exacting. Many persons have, in a small way written histories of parishes and of dioceses ; but few have had the perseverance, the knowledge, and the almost unique gift of the compiler of this Book, Clogher Clergy and Parishes, Canon J. -

The Families of French of Belturbet and Nixon of Fermanagh, and Their

UC 929.2 F8871S 1127710 GENEALOGY COLLECTION \j ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 01239 9322 HUMPHREY FRENCH. "TuK CJouu LuKU Mavuk." 1733-6. See 9-1 J. Lur.l Miiyur of J )ublin, 1732-3, M.P. for Dublin, pp. FroiitUpkrr—Froiii a Mczs.utiiil in pos>:c>i>'io/i <;/' tin lt( r. II. li. Siruirj/. THE FAMILIES French of Belturbet Nixon of Fermanagh -,^Cr ^N^ THEIR DESCENDANTS The Rev. HENRY BIDDALL SWANZY, M.A. iPRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION.^ 1908. DUBLIN : PRIMTED BY ALEX. THOM & CO. LIMITED. PREFATORY NOTE. iiST'T'jf.O An attempt has been made in the following pages to put on record what can be discovered concerning the descendants of two Irish families which became allied in 1737 by the marriage of the Rev. Andrew Nixon with Mariaime French. The various families detailed on pp. 83-127, are descended from that marriage. The PubHc Record Office contains evidence of the existence of many other persons of the names of French and Nixon, who, from the localities in which they lived, were very probably of the same stock, but as no proof of their relationship has been forthcoming, as a rule they have not been mentioned in the book. It has been found necessary to condense the work as much as possible, and to leave out some biographical details which might have been inserted. I have tried in most instances to give chiefly those which come from unfamiliar sources. The evidence for the earlier generations in the 17th and 18th centuries is in almost every case clear and complete. -

N:Vision (Summer 2020)

Issue 61 / Summer 2020 Transforming Community, Radiating Christ FOR I WILL RESTORE HEALTH TO YOU, AND YOUR WOUNDS I WILL HEAL, DECLARES THE LORD...” JEREMIAH 30:17 Children with In this issue of n:vision we CHILDREN WITH ADDITIONAL NEEDS Additional Needs - welcome back familiar faces and 02 old n:vision friends to learn of their lockdown experiences and thoughts. 04 MINISTRY OF HEALING Welcome in Church? A friend of the Diocese, Bishop Tim Wambunya of Butere Diocese in Kenya, rekindled the link between his diocese and 05 BISHOP ANDREW WRITES ours in 2016. This link was originally forged in 1916 when 2 children of Bishop George Chadwick of Derry and Raphoe OUR MAD LIFE worked there as missionaries. Bishop Tim’s many friends in 06 Derry and Raphoe joined in prayer when they learnt of his The Derry and Raphoe Diocesan Board of simple. If the child has sensory issues, will support them - they will know best and it is hospitalisation due to Covid 19. Bishop Tim features on our 08 WELL I WASN’T EXPECTING THAT! Social Responsibity and SEEDS Children’s church cause a meltdown? Will service better than second-guessing. cover, pictured on his release from hospital. Ministry are working together to find sheets be printed in large print? Will there A new friend of the diocese, Bishop Hall Speers of Mahajanga, CHRISTIAN AID MEETS CRISIS Work with Sunday School leaders to make 10 new ways to support children with be somewhere to put a wheelchair, so it originally from the parish of Urney, gives n:vision a glimpse sure material is inclusive. -

Ordained Local Ministry (Olm) Student Handbook 2019-20

ORDAINED LOCAL MINISTRY (OLM) STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-20 CONTENTS Page Introduction Welcome 3 Ordained Local Ministry in the Church of Ireland 4 OLM Programme of Courses Overview 5 OLM Course Exemptions 5 OLM Course Costs 5 Open Learning Administration 6 OLM Certificate 6 Students OLM Student Ordinands 7 Other Open Learning Students 8 Study Skills 9 Individual Spiritual Life 12 University and Colleges Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) 13 Edgehill Theological College (Edgehill) 13 Church of Ireland Theological Institute (CITI) 14 General Regulations 15 Organisation Open Learning Oversight Committee 16 OLM Co-ordinator 16 Workshop Venues 16 Learning Hubs and Students 17 1 CONTENTS (continued) Page Personnel Course Leaders (2019-20) 20 Hub Tutors (2019-20) 21 Course Information Academic Calendar (2019-20) 23 Open Learning Courses (2019-20) 24 Course Assignments and Assessments 27 Coursework Checklist 30 Open Learning Assignment Cover Sheet 31 Academic Offences 32 Libraries Queen’s University (QUB) Library 34 Edgehill Theological College (Edgehill) Library 34 Representative Church Body (RCB) Library 35 2 WELCOME Early on as we began our work as the Open Learning Oversight Committee, it became apparent that an OLM Student Handbook was required. Thanks to the hard-work of our Co-ordinator, the Reverend Ken Rue, that has now come to fruition. I hope you find this to be a helpful guide to all you need to know about the six courses being delivered over the next academic year. Those who began training last year raised a number of pertinent questions over the course of their studies and Ken has attempted to address these so that they don’t become issues again.