2010 Report on Human Rights in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring of Water Level Fluctuations of Darbandikhan Lake Using Remote Sensing Techniques

1 Plant Archives Vol. 20, Supplement 2, 2020 pp. 901-906 e-ISSN:2581-6063 (online), ISSN:0972-5210 MONITORING OF WATER LEVEL FLUCTUATIONS OF DARBANDIKHAN LAKE USING REMOTE SENSING TECHNIQUES Dalshad R. Azeez* 1, Fuad M. Ahmad 2 and Dashne A.K. Karim 2 1College of Agriculture, Kirkuk University, Iraq 2College of Agricultural Engineering, Salahaddin University, Iraq *Corresponding author : [email protected] Abstract Darbandikhan Reservoir Dam is located on the Sirwan (Diyala) River, about 230 km northeast of Baghdad and 65 km southeast of Sulaimaniyah - Iraq. Its borders extend from latitude 35° 06' 58 ''- 35° 21' 07 ''N and longitude 45° 40' 59'' -45° 44' 42'' E. In order to monitor the fluctuation in the level of this lake, Landsat Satellite images were collected for 10 years included, 1984, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2019 for the same time period. Next, the classification of satellite images and the measurement of areas were done using ArcGIS 10.2. In order to study the effect of droughts and wet conditions on water levels in the lake, the standardized precipitation index (SPI) method proposed by Mckee, 1993 was used. In the current study, the 12 months’ time scale SPI values (SPI-12) that was considered individually for the years 1984-2017 were estimated. Each period starts from January and ends in December. It was found that the water level in Darbandikhan Lake has experienced periodic changes during the period from 1984 to 2018. The results also showed that there were some gradual drought trends in the study area according to precipitation changes during the years studied, where severe drought dominated several parts of the study area, and the worst were in the years 1995, 2000, 2915 and 2017. -

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Abu Ghraib District ( ( (

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Abu Ghraib District ( ( ( ( ( ( Idressi Hay Al Askari - ( - 505 Turkey hoor Al basha IQ-P08985 Hamamiyat IQ-P08409 IQ-P08406 Mosul! ! ( ( Erbil ( Syria Iran Margiaba Samadah (( ( ( Baghdad IQ-P08422 ( IQ-P00173 Ramadi! ( ( !\ Al Hay Al Qaryat Askary ( Hadeb Al-Ru'ood Jordan Najaf! IQ-P08381 IQ-P00125 IQ-P00169 ( ( ( ( ( Basrah! ( Arba'at AsSharudi Arabia Kuwait Alef Alf (14000) Albu Khanfar Al Arba' IQ-P08390 IQ-P08398 ( Alaaf ( ( IQ-P00075 ( Al Gray'at ( ( IQ-P08374 ( ( 336 IQ-P08241 Al Sit Alaaf ( (6000) Sabi' Al ( Sabi Al Bur IQ-P08387 Bur (13000) - 12000 ( ( Hasan Sab'at ( IQ-P08438 IQ-P08437 al Laji Alaaf Sabi' Al ( IQ-P00131 IQ-P08435 Bur (5000) ( ( IQ-P08439 ( Hay Al ( ( ( Thaman Alaaf ( Mirad IQ-P08411 Kadhimia District ( as Suki Albu Khalifa اﻟﻛﺎظﻣﯾﺔ Al jdawil IQ-P08424 IQ-P00074 Albu Soda ( Albo Ugla ( (qnatir) ( IQ-P00081 village ( IQ-P00033 Al-Rufa ( IQ-D040 IQ-P00062 IQ-P00105 Anbar Governorate ( ( ( اﻻﻧﺑﺎر Shimran al Muslo ( IQ-G01 Al-Rubaidha IQ-P00174 Dayrat IQ-P00104 ar Rih ( IQ-P00120 Al Rashad Al-Karagul ( Albu Awsaj IQ-P00042 IQ-P00095 IQ-P00065 ( ( ( Albo Awdah Bani Zaid Al-Zuwayiah ( Ad Dulaimiya ( Albu Jasim IQ-P00060 Hay Al Halabsa - IQ-P00117 IQ-P00114 ( IQ-P00022 Falluja District ( ( ( - Karma Uroba Al karma ( Ibraheem ( IQ-P00072 Al-Khaleel اﻟﻔﻠوﺟﺔ Al Husaiwat IQ-P00139 IQ-P00127 ) ( ( Halabsa Al-Shurtan IQ-P00154 IQ-P00031 Karma - Al ( ( ( ( ( ( village IQ-P00110 Ash Shaykh Somod ( ( IQ-D002 IQ-P00277 Hasan as Suhayl ( IQ-P00156 subihat Ibrahim ( IQ-P08189 Muhammad -

Iraq SITREP 2015-5-22

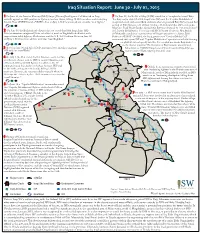

Iraq Situation Report: June 30 - July 01, 2015 1 On June 30, the Interior Ministry (MoI) Suqur [Falcons] Intelligence Cell directed an Iraqi 7 On June 29, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) stated that it “completely cleared” Baiji. airstrike against an ISIS position in Qa’im in western Anbar, killing 20 ISIS members and destroying e Baiji mayor stated that IA, Iraqi Police (IP), and the “Popular Mobilization” Suicide Vests (SVESTs) and a VBIED. Also on July 1, DoD announced one airstrike “near Qa’im.” recaptured south and central Baiji and were advancing toward Baiji Renery and had arrived at Albu Juwari, north of Baiji. On June 30, Federal Police (FP) commander Maj. Gen. Raed Shakir Jawdat claimed that Baiji was liberated by “our armed forces” 2 On June 30, the Baghdadi sub-district director stated that 16th Iraqi Army (IA) and Popular Mobilization Commission (PMC) Deputy Chairman Abu Mahdi Division members recaptured Jubba sub-district, north of Baghdadi sub-district, with al-Muhandis stated that “security forces will begin operations to cleanse Baiji support from tribal ghters, IA Aviation, and the U.S.-led Coalition. Between June 30 Renery of [ISIS].” On July 1, the Iraqi government “Combat Media Cell” and July 1, DoD announced four airstrikes “near Baghdadi.” announced that a joint ISF and “Popular Mobilization” operation retook the housing complex but did not specify whether the complex was inside Baiji district or Dahuk on the district outskirts. e liberation of Baiji remains unconrmed. 3 Between June 30 and July 1 DoD announced two airstrikes targeting Meanwhile an SVBIED targeted an IA tank near the Riyashiyah gas ISIS vehicles “near Walid.” Mosul Dam station south of Baiji, injuring the tank’s crew. -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

![2021 VNR Report [English]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7615/2021-vnr-report-english-227615.webp)

2021 VNR Report [English]

The Republic of Iraq Ministry of Planning National Committee for Sustainable Development The Second National Voluntary Review Report on the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals 2021 Iraq .. And the Path Back to the Development July 2021 Voluntary National Review Report Writing Team Dr. Mahar Hammad Johan, Deputy Minister of Planning, Head of the Report Preparation Team Writing Expert Team Prof. Dr. Hasan Latif Al-Zubaidi / Expert / University of Kufa / College of Administration and Economics Prof. Dr. Wafa Jaafar Al-Mihdawi / Expert / Mustansiriyah University / College of Administration and Economics Prof. Dr. Adnan Yasin Mustafa / Expert / University of Baghdad / College of Education for Girls Supporting International organizations United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) – Iraq United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) Technical Team Dr. Azhar Hussein Saleh / Administrative Deputy of Minister of Planning Dr. Dia Awwad Kazem / Head of the Central Statistics Organization Mr. Maher Abdul-Hussein Hadi / Director General of the National Center for Administrative Development and Information Technology Dr. Mohamed Mohsen El-Sayed / Director General of the Department of Regional and Local Development Dr. Alaa El-Din Jaafar Mohamed / Director General of the Department of Financial and Economic Policies Dr. Maha Abdul Karim Hammoud / Director General of the Department of Human Development Ms. Naglaa Ali Murad / Director of the Social Fund for Development Mr. Abdel-Zahra Mohamed Waheed / Director of the Department of Information and Government Communications Dr. Amera Muhammad Hussain / Umm Al-Yateem Foundation for Development Mrs. Ban Ali Abboud / Expert / Department of Regional and Local Development Ms. Mona Adel Mahdi / Senior Engineer / Department of Regional and Local Development Supporting Team Mr. -

Iraq 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The 2018 parliamentary elections, while imperfect, generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to Adil Abd al-Mahdi. On December 1, in response to protesters’ demands for significant changes to the political system, Abd al-Mahdi submitted his resignation, which the Iraqi Council of Representatives (COR) accepted. As of December 17, Abd al-Mahdi continued to serve in a caretaker capacity while the COR worked to identify a replacement in accordance with the Iraqi constitution. Numerous domestic security forces operated throughout the country. The regular armed forces and domestic law enforcement bodies generally maintained order within the country, although some armed groups operated outside of government control. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) consist of administratively organized forces within the Ministries of Interior and Defense, and the Counterterrorism Service. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for domestic law enforcement and maintenance of order; it oversees the Federal Police, Provincial Police, Facilities Protection Service, Civil Defense, and Department of Border Enforcement. Energy police, under the Ministry of Oil, are responsible for providing infrastructure protection. Conventional military forces under the Ministry of Defense are responsible for the defense of the country but also carry out counterterrorism and internal security operations in conjunction with the Ministry of Interior. The Counterterrorism Service reports directly to the prime minister and oversees the Counterterrorism Command, an organization that includes three brigades of special operations forces. The National Security Service (NSS) intelligence agency reports directly to the prime minister. -

Health Sector

Electricity Sector Project's name Location Capacity Province 1 Al-Yusfiya Gas Al-Yusfiya 1500 Mega Baghdad Station Project Watt (Combined Cycle) - Communication Sector None Health Sector No Project’s Name Type of Province Investment Opportunities 1. General hospital, capacity: (400) beds- New Baghdad/ Al-Rusafa/ 15 buildings ( 12 main healthcare construction Bismayah New City centers / (1) typical healthcare center, specialized medical center). 2. Specialized cancer treatment center New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- construction Rusafa 3. Arabic Child Hospital in Al-Karkh (50 New Baghdad/ Al-Karkh beds) construction 4. 3-4 Drugs and medical appliances New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- factory. construction Rusafa 5. 1 Sterility and fertility hospital, New Baghdad in Al Karkh and Capacity: (50 beds) construction Al-Rusafa 6. 1 Specialized ophthalmology hospital New Baghdad , Al Karkh and Al- Capacity : ( 50 beds ) construction Rusafa 7. 1 Specialized cardiac surgery hospital New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- capacity : (100 beds) construction Rusafa 8. Specialized Plastic surgery hospital New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- (50 beds) construction Rusafa 9. 2-3 hydrogen peroxide (pure New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- O2)Plant Construction Rusafa 10. Complete medical city New Baghdad , Al Karkh and Al- construction Rusafa 11. 4 General hospitals , capacity: 100 bed New Baghdad, Al-Karkh and Al- each construction Rusafa 12. 4 Specialized medical centers, New Baghdad , Al-Karkh and Al- capacity : (50 bed) construction Rusafa Housing and Infrastructure sector No. Project name Location allocatd Province area 1. Establishment of Housing Complex (According Al-Tarimiyah 5609 Baghdad to investor’s economic visibility). District/Abo-Serioel Dunam and Quarter. -

Diyala Governorate, Kifri District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Diyala Governorate, Kifri( District ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( Daquq District ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Omar Sofi Kushak ( Kani Ubed Chachan Nawjul IQ-P23893 IQ-P05249 Kharabah داﻗوق ) ) IQ-P23842 ( ( IQ-P23892 ( Chamchamal District ( Galalkawa ( IQ-P04192 Turkey Haji Namiq Razyana Laki Qadir IQ-D074 Shekh Binzekhil IQ-P05190 IQ-P05342 ) )! ) ﺟﻣﺟﻣﺎل ) Sarhang ) Changalawa IQ-P05159 Mosul ! Hawwazi IQ-P04194 Alyan Big Kozakul IQ-P16607 IQ-P23914 IQ-P05137 Erbil IQ-P05268 Sarkal ( Imam IQ-D024 ( Qawali ( ( Syria ( IranAziz ( Daquq District Muhammad Garmk Darka Hawara Raqa IQ-P05354 IQ-P23872 IQ-P05331 Albu IQ-P23854 IQ-P05176 IQ-P052B2a6 ghdad Sarkal ( ( ( ( ( ! ( Sabah [2] Ramadi ( Piramoni Khapakwer Kaka Bra Kuna Kotr G!\amakhal Khusraw داﻗوق ) ( IQ-P23823 IQ-P05311 IQ-P05261 IQ-P05235 IQ-P05270 IQ-P05191 IQ-P05355 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Jordan ( ( ! ( ( ( IQ-D074 Bashtappa Bash Tappa Ibrahim Big Qala Charmala Hawara Qula NaGjafoma Zard Little IQ-P23835 IQ-P23869 IQ-P05319 IQ-P05225 IQ-P05199 ( IQ-P23837 ( Bashtappa Warani ( ( Alyan ( Ahmadawa ( ( Shahiwan Big Basrah! ( Gomatzbor Arab Agha Upper Little Tappa Spi Zhalan Roghzayi Sarnawa IQ-P23912 IQ-P23856 IQ-P23836 IQ-P23826 IQ-P23934 IQ-P05138 IQ-P05384 IQ-P05427 IQ-P05134 IQ-P05358 ( Hay Al Qala [1] ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Ibrahim Little ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Ta'akhi IQ-P23900 Tepe Charmuk Latif Agha Saudi ArabiaKhalwa Kuwait IQ-P23870 Zhalan ( IQ-P23865 IQ-P23925 ( ( IQ-P23885 Sulaymaniyah Governorate Roghzayi IQ-P05257 ( ( ( ( ( Wa(rani -

Iraq Governance & Performance Accountability Project (Igpa/Takamul)

IRAQ GOVERNANCE & PERFORMANCE ACCOUNTABILITY PROJECT (IGPA/TAKAMUL) FY21 QUARTER-1 REPORT October 1, 2020 – December 31, 2020 Program Title Iraq Governance and Performance Accountability Project (IGPA/Takamul) Sponsoring USAID Office USAID Iraq Contract Number AID-267-H-17-00001 Contractor DAI Global LLC Date of publication January 30, 2021 Author IGPA/Takamul Project Team COVER: A water treatment plant subject to IGPA/Takamul’s assessment in Hilla City, Babil Province | Photo Credit: Pencils Creative for USAID IGPA/Takamul This publication, prepared by DAI, was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: PROJECT PROGRESS ...................................................................................................................... 3 OBJECTIVE 1: ENHANCED SERVICE DELIVERY CAPACITY OF THE GOVERNMENT OF IRAQ ................................................................................................................................. 3 SUCCESS STORY ...................................................................................................................................................... 21 OBJECTIVE 2: IMPROVED PROVINCIAL AND NATIONAL -

Evaluating the US Military 'Surge' Using Nighttime Light Signatures

Baghdad Nights: Evaluating the US Military ‘Surge’ Using Nighttime Light Signatures John Agnew Thomas W. Gillespie Jorge Gonzalez Brian Min CCPR-064-08 December 2008 Latest Revised: December 2008 California Center for Population Research On-Line Working Paper Series Environment and Planning A 2008, volume 40, pages 2285 ^ 2295 doi:10.1068/a41200 Commentary Baghdad nights: evaluating the US military `surge' using nighttime light signatures Introduction Geographers and social scientists find it increasingly difficult to intervene in debates about vital matters of public interest, such as the Iraq war, because of the ideological polarization and lack of respect for empirical analysis that have afflicted US politics in recent years. In this commentary we attempt to intervene in a way that applies some fairly objective and unobtrusive measures to a particularly contentious issue: the question of whether or not the so-called `surge' of US military personnel into Baghdadö30 000 more troops added in the first half of 2007öhas turned the tide against political and social instability in Iraq and laid the groundwork for rebuilding an Iraqi polity following the US invasion of March 2003. Even though US media attention on the Iraq war has waned, the conflict remains a material and symbolic issue of huge significance for both future US foreign policy and the future prospects of Iraq as an effective state. It has been difficult to assess whether the so-called surge or escalation of US troops into Baghdad beginning in spring 2007 has led to lower levels of violence, political reconciliation, and improvements in the quality of life of the city's population. -

UN Assistance Mission for Iraq ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة (UNAMI) ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة

ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة .UN Assistance Mission for Iraq 1 ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة ﻟﻠﻌﺮاق (UNAMI) Human Rights Report 1 January – 31 March 2007 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS..............................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................2 PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS.......................................................................................................4 EXTRA-JUDICIAL EXECUTIONS AND TARGETED AND INDISCRIMINATE KILLINGS .........................................4 EDUCATION SECTOR AND THE TARGETING OF ACADEMIC PROFESSIONALS ................................................8 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION .........................................................................................................................10 MINORITIES...............................................................................................................................................13 PALESTINIAN REFUGEES ............................................................................................................................15 WOMEN.....................................................................................................................................................16 DISPLACEMENT -

Iraq- Salah Al-Din Governorate, Daur District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Salah al-Din Governorate, Daur District ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Raml ( Shibya Al-qahara ( Sector 41 - Al Khazamiya Mukhaiyam Tmar Zagilbana ( IQ-P16758 abdul aziz IQ-P16568 Summaga Al Sharqiya - illegal Kirkuk District IQ-P16716 Muslih IQ-P16862 IQ-P16878 Turkey Albu IQ-P23799 Ramel [1] IQ-P16810 ( Upper Sabah [2] Shahatha Abdul Aziz Zajji IQ-P16829 IQ-P23823 IQ-P16757 IQ-P16720 IQ-P16525 ( Khashamina ﻛرﻛوك ( ( Albu IQ-P16881 Mosul! ! ( ( IQ-P23876 ( Shahiwan Sabah [1] Albu shahab Erbil ( Gheda IQ-P23912 IQ-D076 TALAA IQ-P16553 IQ-P16554 ( IQ-P16633 ( Tamur Syria Iran AL-Awashra AL-DIHEN ( ( ( Tamour IQ-P16848 Hulaiwa Big IQ-P16545 IQ-P16839 Baghdad ( ( IQ-P16847 IQ-P23867 ( ( Khan Mamlaha ( ( Ramadi! !\ IQ-P23770 Dabaj Al Jadida ( Salih Hulaiwa ( ( ( ( IQ-P23849 village Al Mubada AL- Ugla (JLoitrtlde an Najaf! (( IQ-P23671 village IQ-P16785 IQ-P23868 ( ( Ta`an ( Daquq District ( IQ-P23677 Al-Mubadad Basrah! IQ-P23804 ( Maidan Yangija ( IQ-P16566 Talaa dihn ( IQ-P16699 Albu fshka IQ-P23936 داﻗوق ) Al Washash al -thaniya ( Khashamila KYuawnija( iBtig village IQ-P16842 IQ-P16548 Albu zargah Saudi Arabia Tal Adha ( IQ-P23875 IQ-P23937 IQ-P23691 IQ-D074 ( IQ-P16557 ( ( ( Talaa dihn ( IQ-P16833 ( al-aula Alam Bada IQ-P16843 ( IQ-P23400 Mahariza ( IQ-P16696 ( Zargah ( IQ-P16886 Ajfar Kirkuk Governorate ( Qaryat Beer Chardaghli Sector 30 IQ-P23393 Ahmed Mohammed Shallal IQ-P23905 IQ-P23847 ﻛرﻛوك ) Al Rubidha ( ( ( Abdulaziz Bi'r Ahmad ( IQ-P23798 ( IQ-G13