Hospitality in a Cistercian Abbey: the Case of Kirkstall in the Later Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoroton Society Publications

THOROTON SOCIETY Record Series Blagg, T.M. ed., Seventeenth Century Parish Register Transcripts belonging to the peculiar of Southwell, Thoroton Society Record Series, 1 (1903) Leadam, I.S. ed., The Domesday of Inclosures for Nottinghamshire. From the Returns to the Inclosure Commissioners of 1517, in the Public Record Office, Thoroton Society Record Series, 2 (1904) Phillimore, W.P.W. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. I: Henry VII and Henry VIII, 1485 to 1546, Thoroton Society Record Series, 3 (1905) Standish, J. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. II: Edward I and Edward II, 1279 to 1321, Thoroton Society Record Series, 4 (1914) Tate, W.E., Parliamentary Land Enclosures in the county of Nottingham during the 18th and 19th Centuries (1743-1868), Thoroton Society Record Series, 5 (1935) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem and other Inquisitions relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. III: Edward II and Edward III, 1321 to 1350, Thoroton Society Record Series, 6 (1939) Hodgkinson, R.F.B., The Account Books of the Gilds of St. George and St. Mary in the church of St. Peter, Nottingham, Thoroton Society Record Series, 7 (1939) Gray, D. ed., Newstead Priory Cartulary, 1344, and other archives, Thoroton Society Record Series, 8 (1940) Young, E.; Blagg, T.M. ed., A History of Colston Bassett, Nottinghamshire, Thoroton Society Record Series, 9 (1942) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Bonds and Allegations for Marriage Licenses in the Archdeaconry Court of Nottingham, 1754-1770, Thoroton Society Record Series, 10 (1947) Blagg, T.M. -

Issue 3 Autumn 2010 Kirkstall Abbey and Abbey House Museum

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2010 In this issue: Kirkstall Abbey and Abbey House Museum Mysterious Carved Rocks on Ilkley Moor Along the Hambleton Drove Road The White Horse of Kilburn The Notorious Cragg Vale Coiners The Nunnington Dragon Hardcastle Crags in Autumn Hardcastle Crags is a popular walking destination, most visitors walk from Hebden Bridge into Hebden Dale. (also see page 13) 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2010 Left: Fountains Cottage near the western gate of Fountains Abbey. Photo by Jeremy Clark Cover: Cow and Calf Rocks, Ilkley Moor Editorial utumn marks the transition from summer into winter when the arrival of night becomes noticeably earlier. It is also a great time to enjoy a walk in one of Yorkshire’s beautiful woodlands with their A magnificent display of red and gold leaves. One particularly stunning popular autumn walk is Hardcastle Crags with miles of un-spoilt woodland owned by the National Trust and starts from Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire. In this autumn issue we feature beautiful photos of Hardcastle Crags in Autumn, and days out, for example Kirkstall Abbey and Abbey House Museum, Leeds, Mysterious carved rocks on Ilkley Moor, the Hambleton Drove Road and the White Horse of Kilburn. Also the story of the notorious Cragg Vale coiners and a fascinating story of the Nunnington Dragon and the knight effigy in the church of All Saints and St. James, Ryedale. In the Autumn issue: A Day Out At Kirkstall Abbey And Abbey The White Horse Of Kilburn That Is Not A House Museum,-Leeds True White Horse Jean Griffiths explores Kirkstall Abbey and the museum. -

ASPECTS of Tile MONASTIC PATRONAGE of Tile ENGLISH

ASPECTS OF TIlE MONASTIC PATRONAGE OF TIlE ENGLISH AND FRENCH ROYAL HOUSES, c. 1130-1270 by Elizabeth M. Hallani VC i% % Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in History presented at the University of London. 1976. / •1 ii SUMMARY This study takes as its theme the relationship of the English and French kings and the religious orders, £.1130-1270, Patronage in general is a field relatively neglected in the rich literature on the monastic life, and royal patronage has never before been traced over a broad period for both France and England. The chief concern here is with royal favour shown towards the various orders of monks and friars, in the foundations and donations made by the kings. This is put in the context of monastic patronage set in a wider field, and of the charters and pensions which are part of its formaL expression. The monastic foundations and the general pattern of royal donations to different orders are discussed in some detail in the core of the work; the material is divided roughly according to the reigns of the kings. Evidence from chronicles and the physical remains of buildings is drawn upon as well as collections of charters and royal financial documents. The personalities and attitudes of the monarchs towards the religious hierarchy, the way in which monastic patronage reflects their political interests, and the contrasts between English and French patterns of patronage are all analysed, and the development of the royal monastic mausoleum in Western Europe is discussed as a special case of monastic patronage. A comparison is attempted of royal and non-royal foundations based on a statistical analysis. -

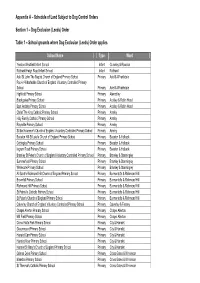

Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1

Appendix A – Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1 – Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order Table 1 – School grounds where Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order applies School Name Type Ward Yeadon Westfield Infant School Infant Guiseley & Rawdon Rothwell Haigh Road Infant School Infant Rothwell Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Pool-in-Wharfedale Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Highfield Primary School Primary Alwoodley Blackgates Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood East Ardsley Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood Christ The King Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Holy Family Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Raynville Primary School Primary Armley St Bartholomew's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Armley Beeston Hill St Luke's Church of England Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Cottingley Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Ingram Road Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Bramley St Peter's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Summerfield Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Whitecote Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Brownhill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Richmond Hill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill St Patrick's Catholic Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill -

The Case of the Beaulieu Abbey

acoustics Article An Archaeoacoustics Analysis of Cistercian Architecture: The Case of the Beaulieu Abbey Sebastian Duran *, Martyn Chambers * and Ioannis Kanellopoulos * School of Media Arts and Technology, Solent University (Southampton), East Park Terrace, Southampton SO14 0YN, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.D.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (I.K.) Abstract: The Cistercian order is of acoustic interest because previous research has hypothesized that Cistercian architectural structures were designed for longer reverberation times in order to reinforce Gregorian chants. The presented study focused on an archaeoacacoustics analysis of the Cistercian Beaulieu Abbey (Hampshire, England, UK), using Geometrical Acoustics (GA) to recreate and investigate the acoustical properties of the original structure. To construct an acoustic model of the Abbey, the building’s dimensions and layout were retrieved from published archaeology research and comparison with equivalent structures. Absorption and scattering coefficients were assigned to emulate the original room surface materials’ acoustics properties. CATT-Acoustics was then used to perform the acoustics analysis of the simplified building structure. Shorter reverbera- tion time (RTs) was generally observed at higher frequencies for all the simulated scenarios. Low speech intelligibility index (STI) and speech clarity (C50) values were observed across Abbey’s nave section. Despite limitations given by the impossibility to calibrate the model according to in situ measurements conducted in the original structure, the simulated acoustics performance suggested Citation: Duran, S.; Chambers, M.; how the Abbey could have been designed to promote sacral music and chants, rather than preserve Kanellopoulos, I. An Archaeoacoustics high speech intelligibility. Analysis of Cistercian Architecture: The Case of the Beaulieu Abbey. -

Catalogue of Photographs of Wales and the Welsh from the Radio Times

RT1 Royal Welsh Show Bulls nd RT2 Royal Welsh Show Sheep shearing nd RT3 Royal Welsh Show Ladies choir nd RT4 Royal Welsh Show Folk dance 1992 RT5 Royal Welsh Show Horses nd RT6 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1962 RT7 LLangollen Tilt Dancers 1962 RT8 Llangollen Tilt Estonian folk dance group 1977 RT9 Llangollen Eisteddfod Dancers 1986 RT10 Royal Welsh Show Horse and rider 1986 RT11 Royal Welsh Show Horse 1986 RT12 Royal Welsh Show Pigs 1986 RT13 Royal Welsh Show Bethan Charles - show queen 1986 RT14 Royal Welsh Show Horse 1986 RT15 Royal Welsh Show Sheep shearing 1986 RT16 Royal Welsh Show Sheep shearing 1986 RT17 Royal Welsh Show Produce hall 1986 RT18 Royal Welsh Show Men's tug of war 1986 RT19 Royal Welsh Show Show jumping 1986 RT20 Royal Welsh Show Tractors 1986 RT21 Royal Welsh Show Log cutting 1986 RT22 Royal Welsh Show Ladies in welsh costume, spinning wool 1986 RT23 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1986 RT24 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1986 RT25 Royal Welsh Show Men's tug of war 1986 RT26 Royal Welsh Show Audience 1986 RT27 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1986 RT28 Royal Welsh Show Vehicles 1986 RT29 Royal Welsh Show Sheep 1986 RT30 Royal Welsh Show General public 1986 RT31 Royal Welsh Show Bulls 1986 RT32 Royal Welsh Show Bulls 1986 RT33 Merionethshire Iowerth Williams, shepherd nd RT34 LLandrindod Wells Metropole hotel nd RT35 Ebbw Vale Steel works nd RT36 Llangollen River Dee nd RT37 Llangollen Canal nd RT38 Llangollen River Dee nd RT39 Cardiff Statue of St.David, City Hall nd RT40 Towyn Floods 1990 RT41 Brynmawr Houses and colliery nd RT42 Llangadock Gwynfor Evans, 1st Welsh Nationalist MP 1966 RT43 Gwynedd Fire dogs from Capel Garman nd RT44 Anglesey Bronze plaque from Llyn Cerrigbach nd RT45 Griff Williams-actor nd RT46 Carlisle Tullie House, museum and art gallery nd RT47 Wye Valley Tintern Abbey nd 1 RT48 Pontypool Trevethin church nd RT49 LLangyfelach church nd RT50 Denbighshire Bodnant gardens nd RT51 Denbighshire Glyn Ceiriog nd RT52 Merthyr New factory and Cyfartha castle nd RT53 Porthcawl Harbour nd RT54 Porthcawl Harbour nd RT55 Gower Rhosili bay nd RT56 St. -

A Short Guide to Castell Dinas Bran

11/12/2018 Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust - Education - Guides - Dinas Bran Cymraeg / English A short guide to Castell Dinas Bran by the Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust Castell Dinas Bran (OS national grid reference SJ222430) is both a hillfort and medieval castle. The Iron Age defences and medieval castle are located high above the valley of the Dee overlooking Llangollen. The castle is sited on a long rectangular platform which may have been artificially levelled. The ground drops away steeply on all sides but particularly to the north with its crags and cliffs. The site is a scheduled ancient monument. The hillfort has a single bank and ditch enclosing an area of about 1.5 hectares. To the south and west the defences are most considerable being up to 8 metres high in places. The entrance lies in the south-west corner of the fort and is defended by an inward curving bank. To the north the fort is defended by the natural steepness of the land and no earthwork defences were required. The castle was built towards the later part of the 13th century by the princes of Powys Fadog and was the site of a meeting between the sons of Gryffydd Maelor in 1270 when they granted the lands of Maelor Saesneg for the upkeep of their mother, Emma Audley. During the wars between Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, Prince of Wales and Edward I of England the castle was burnt by the Welsh before it was captured in 1277 by Henry de Lacy, earl of Lincoln. It was not repaired and ceased to be used after the 1280s. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Joseph Ritson and the Publication of Early English Literature Genevieve Theodora McNutt PhD in English Literature University of Edinburgh 2018 1 Declaration This is to certify that that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Portions of the final chapter have been published, in a condensed form, as a journal article: ‘“Dignified sensibility and friendly exertion”: Joseph Ritson and George Ellis’s Metrical Romance(ë)s.’ Romantik: Journal for the Study of Romanticisms 5.1 (2016): 87-109. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/rom.v5i1.26422. Genevieve Theodora McNutt 2 3 Abstract This thesis examines the work of antiquary and scholar Joseph Ritson (1752-1803) in publishing significant and influential collections of early English and Scottish literature, including the first collection of medieval romance, by going beyond the biographical approaches to Ritson’s work typical of nineteenth- and twentieth- century accounts, incorporating an analysis of Ritson’s contributions to specific fields into a study of the context which made his work possible. -

Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Doncaster

Near by - Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet, Sheffield Aeroventure, Doncaster Brodsworth Hall and Gardens, Doncaster Cannon Hall Museum, Barnsley Conisbrough Castle and Visitors' Centre, Doncaster Cusworth Hall/Museum of South Yorkshire Life, Doncaster Elsecar Heritage Centre, Barnsley Eyam Hall, Eyam,Derbyshire Five Weirs Walk, Sheffield Forge Dam Park, Sheffield Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield Magna Science Adventure Centre, Rotherham Markham Grange Steam Museum, Doncaster Museum of Fire and Police, Sheffield Peveril Castle, Castleton, Derbyshire Sheffield and Tinsley Canal Trail, Sheffield Sheffield Bus Museum, Sheffield Sheffield Manor Lodge, Sheffield Shepherd's Wheel, Sheffield The Trolleybus Museum at Sandtoft, Doncaster Tropical Butterfly House, Wildlife and Falconry Centre, Nr Sheffeild Ultimate Tracks, Doncaster Wentworth Castle Gardens, Barnsley) Wentworth Woodhouse, Rotherham Worsbrough Mill Museum & Country Park, Barnsley Wortley Top Forge, Sheffield Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Doncaster West Yorkshire Abbey House Museum, Leeds Alhambra Theatre, Bradford Armley Mills, Leeds Bankfield Museum, Halifax Bingley Five Rise Locks, Bingley Bolling Hall, Bradford Bradford Industrial Museum, Bradford Bronte Parsonage Museum, Haworth Bronte Waterfall, Haworth Chellow Dean, Bradford Cineworld Cinemas, Bradford Cliffe Castle Museum, Keighley Colne Valley Museum, Huddersfield Colour Museum, Bradford Cookridge Hall Golf and Country Club, Leeds Diggerland, Castleford Emley Moor transmitting station, Huddersfield Eureka! The National Children's Museum, -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Early Transport on Exmoor by Jan Lowy

Early transport on Exmoor By Jan Lowy This work is based on notes made for the presentation to the Local History Group, December 2020 Map of West Somerset to Tiverton This shows the area we are mainly talking about. This map is dated 1794. Packhorse bridge at Clickit For centuries men used feet to get about, then horses, then horse and cart, and horse and carriage. There were also boats on rivers and round the coast. On land they needed marked routes to follow, which needed to be kept clear. Stone age people travelled long distances in search of suitable flints for their tools and weapons, but it was during the Bronze age (3000 – 1200BC) that tracks were regularly used - probably something like this. Often on high ground, enabling travellers to see hazards more easily, including those with criminal intentions, avoiding densely wooded and marshy river valleys until forced to descend to cross streams. Just off road to Webbers Post Many modern roads follow the same route: long distance routes such as across the Blackdown and Brendon hills linking the ridgeways of Dorset and Wiltshire with Devon, (as here) and local routes, like tracks along the Quantocks, Mendips and Poldens. As we know, the Romans built a national system of good roads, but after the Romans left the roads were not maintained. There were not many wheeled vehicles, and fewer long journeys, so only local tracks were needed. By the Middle Ages, there was again considerable traffic on the roads. Each parish was responsible for maintaining the roads within its bounds. -

A Lunchtime Stroll in Leeds City Centre

2 kilometres / 30 minutes to 1 hour. Accessibility – All this route is on pavements and avoids steps. A lunchtime stroll in Leeds City Centre There are numerous bridges and river crossings in Leeds. However, there is only one referred to affectionately as “Leeds Bridge”. This is where our walk starts. There has been some form of crossing here since the middle ages. The bridge you see today was built out of cast iron in the early 1870's. In 1888 the bridge was witness to a world first. The “Father of Cinematography”, Louis Le Prince, shot what is considered to be the world’s earliest moving pictures from the bridge. © It's No Game (cc-by-sa/2.0) Walk across Leeds Bridge and take a right along Dock Street. Dock Street began its life as a commercial entity in the 1800's. Then, during the Industrial Revolution, the canal network provided the catalyst for the city's growth. As its name suggests, boats used to dock along Dock Street. A deep dock allowed the loading and unloading of barges into warehouses. Today Dock Street still looks familiar, but the warehouses have become housing and business spaces. Converted and conserved in the 1980's. Continuing along Dock Street you will pass Centenary Bridge. This bridge was built in 1993 to celebrate 100 years since Leeds was granted city status. It also created better pedestrian access across the Aire. Dock Street c. 1930 By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net Continue along Dock Street and you will come to Brewery Wharf.