Qt3k43832x.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2-009.01 Santa Clara Valley - Niles Cone

2-009.01 SANTA CLARA VALLEY - NILES CONE Basin Boundaries Summary The Niles Cones groundwater subbasin is a portion of the Santa Clara Valley groundwater gasin in California. The northern boundary of the subbasin is the statutory boundary of the Alameda County Water District (ACWD). The eastern boundary is the Diablo Mountain Range. The southern boundary is Coyote Creek and Santa Clara County. The western boundary is the San Francisco Bay. The boundary is defined by 6 segments detailed in the descriptions below. Segment Descriptions Segment Segment Description Ref Label Type 1-2 I Begins from point (1) and follows the Alameda County Water District Statutory {a} Water boundary to point (2). Agency 2-3 I Begins from point (1) and follows the Alameda County Water District Statutory {a} Water boundary to point (2). Agency 3-4 E Continues from point (2) and follows the contact of Alluvium with various {b} Alluvial marine sedimentary rocks to point (3). 4-5 I Continues from point (3) and follows the Alameda and Santa Clara County {c} County Boundary to point (4). 5-6 I Continues from point (4) and follows Coyote Creek to point (5). {d} Stream 6-7 E Continues from point (5) and follows the San Francisco Bay to point (6). {d} Ocean 7-1 E Continues from point (6) and follows the Alameda County Water District {a} Water Statutory boundary to the end at point (1). Agency Page 1 of 3 02/05/18 3:49 PM Significant Coordinates Point Latitude Longitude 1 37.649387754 -122.155370502 2 37.617682554 -122.101084144 3 37.611327957 -122.02363347 4 37.470391831 -121.889169705 5 37.453950119 -121.924732232 6 37.466631797 -121.997018393 7 37.581516338 -122.143414204 Page 2 of 3 02/05/18 3:49 PM Map 2-009.01 SANTA CLARA VALLEY - NILES CONE https://sgma.water.ca.gov/webgis/?appid=160718113212&subbasinid=2-009.01 References Ref Citation Pub Global Date ID {a} California Department of Water Resources (DWR), Water Agencies Dataset.URL: 2016 48 https://gis.water.ca.gov/app/bbat/ {b} California Geological Survey (CGS), Regional Geologic Map No. -

Distribution of the Draft Eis

CHAPTER 12: DISTRIBUTION OF THE DRAFT EIS The Draft EIS was transmitted to the officials, agencies, organizations, and individuals listed in this chapter. The Draft EIS is available for review during normal business hours at several libraries in Santa Clara and Alameda counties and at the VTA office at 3331 North First Street, Building B in San Jose. Copies of the document may be obtained by contacting VTA at (408) 321-5789. VTA has notified all property owners/tenants who may be impacted by the Build Alternatives and has advertised the availability of the EIS in local periodicals, including the Fremont Argus, San Jose Mercury News, The Milpitas Post, El Observador, Thoi Boa, and Santa Clara Weekly. See Chapter 11.0: Agency and Community Participation for additional information. 12.1 PUBLIC OFFICIALS Federal Elected Officials The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Barbara Boxer U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate District 8 501 First Street, Suite 7-600 450 Golden Gate Avenue, 14th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 San Francisco, CA 94102 The Honorable Diane Feinstein The Honorable Barbara Lee U.S. Senate U.S. House of Representatives 1 Post Street, Suite 2450 District 9 San Francisco, CA 94104 1301 Clay Street, Suite 1000-N Oakland, CA 94612 The Honorable George Miller U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Ellen Tauscher District 7 U.S. House of Representatives 1333 Willow Pass Road District 10 Concord, CA 94520 2121 North California Boulevard, Suite 555 Walnut Creek, CA 94596 Agencies and Organizations Notified of Draft EIS Availability 12-1 Silicon Valley Rapid Transit Corridor EIS The Honorable Jerry McNerney State Elected Officials U.S. -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

2021 Santa Clara County Multi-Jurisdictional Program for Public Information

CONSENT CALENDAR Agenda Item # 4 AGENDA REPORT SUMMARY Meeting Date: July 13, 2021 Subject: 2021 Santa Clara County Multi-Jurisdictional Program for Public Information Prepared by: Steve Golden, Senior Planner Reviewed by: Jon Biggs, Community Development Director Approved by: Brad Kilger, Interim City Manager Attachment: 1. Resolution 2. 2021 Santa Clara County Multi-Jurisdictional PPI (Five-Year Plan) Initiated by: Staff Previous Council Consideration: None Fiscal Impact: None Environmental Review: Not applicable Policy Question(s) for Council Consideration: • None Summary: • The City currently has a Community Rating System Classification of 8, which allows property owners in the Special Flood Hazard Areas to receive a 10% discount on flood insurance premiums through the National Flood Insurance Program for all new or renewed policies by residents and businesses. • The Program for Public Information is a program under the Community Rating System (CRS) which contributes to achieving the Class 8 rating. The Federal Emergency Management Agency requires the elected body of each community to approve the Program for Public Information in order to receive credit for having a plan pursuant to the CRS guidelines. Staff Recommendation: Approve the 2021 Santa Clara County Multi-Jurisdictional Program for Public Information Reviewed By: Interim City Manager City Attorney Acting Finance Director BK JH JM Subject: Approve the 2021 Santa Clara County Multi-Jurisdictional Program for Public Information (Five-Year Plan) Purpose Approve the 2021 Santa Clara County Multi-Jurisdictional Program for Public Information so the City is eligible to receive credit under the National Flood Insurance Program’s Community Rating System program. Background On April 14, 2015, Valley Water’s Board adopted the original 2015 Santa Clara County Multi- Jurisdictional Program for Public Information (PPI) Five Year Plan. -

Waterfall Hikes

Waterfall Hikes of the Peninsula and South Bay HIKE LOCATIONS PROTECTED LAND COUNTY, STATE, AND NATIONAL PARKS, REGIONAL PRESERVES, AND POSTPROTECTED LAND Berry Creek Falls Big Basin Redwoods State Park 1 MILEAGE 9.5 MILE LOOP ELEVATION 3,200 FT SEASON ALL YEAR ROUTE FROM THE PARK HEADQUARTERS, FOLLOW THE SUNSET TRAIL TO THE BERRY CREEK FALLS TRAIL AND SKYLINE TO SEA TRAIL Big Basin is home to some of the biggest trees and waterfalls in the Santa Cruz Mountains. In the late spring, listen carefully for endangered marbled murrelets nesting near this waterfall. Trail Map Back to Map Gnissah 2011 POST protects and cares for open space, farms, and parkland in and around Silicon Valley. www.openspacetrust.org Tiptoe Falls Pescadero Creek County Park 2 MILEAGE 1.2 MILES ROUND TRIP ELEVATION 500 FT SEASON WINTER, SPRING ROUTE FROM THE PARK HEADQUARTERS, FOLLOW PORTOLA STATE PARK ROAD TO TIPTOE FALLS TRAIL. RETRACE YOUR STEPS This short and relatively easy trail to Tiptoe Falls makes this hike enjoy- able for the whole family. You’ll find this waterfall on Fall Creek - a short, steep tributary of Pescadero Creek. Trail Map Visit Preserve Back to Map Aleksandar Milovojevic 2011 POST protects and cares for open space, farms, and parkland in and around Silicon Valley. www.openspacetrust.org Kings Creek Falls Castle Rock State Park 3 MILEAGE 3 MILE LOOP ELEVATION 1,110 FT SEASON WINTER, SPRING ROUTE FROM SKYLINE BLVD, FOLLOW THE SARATOGA GAP TRAIL TO THE INTERCONNECTOR TRAIL AND RIDGE TRAIL The tranquility found at Kings Creek Falls is just one of the many treasures found at Castle Rock State Park. -

Annual Survey

ANNUAL SURVEY March 2019 Fiscal Year 2017-18 Bay Area Water Supply and Conservation Agency FY 2017-18 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BAWSCA OVERVIEW PAST AND CURRENT PURCHASES FROM SFPUC TOTAL WATER SUPPLY AND DEMAND CURRENT WATER USE BY CUSTOMER CLASS CLIMATOLOGICAL DATA SERVICE AREA POPULATIONS CURRENT WATER USE PER CAPITA CURRENT RESIDENTIAL WATER BILLS AGENCY PROFILES MARCH 2019 BAWSCA WATER FACTS AT-A-GLANCE – FY 2017-18 BAWSCA Member Agencies San Mateo County - City of Brisbane / Guadalupe Valley Municipal Improvement District, City of Burlingame, California Water Service Company (Bear Gulch District, Mid-Peninsula District, South San Francisco District), Coastside County Water District, City of Daly City, City of East Palo Alto, Estero Municipal Improvement District, Town of Hillsborough, City of Menlo Park, Mid-Peninsula Water District, City of Millbrae, North Coast County Water District, City of Redwood City, City of San Bruno, and Westborough Water District Santa Clara County - City of Milpitas, City of Mountain View, City of Palo Alto, Purissima Hills Water District, San Jose Municipal Water System – North, City of Santa Clara, Stanford University, and City of Sunnyvale Alameda County - Alameda County Water District, City of Hayward Service Areas Size (sq. mi.) Population Number of Agencies San Mateo County 185 746,013 16 Santa Clara County 117 561,898 8 Alameda County 166 516,500 2 Total 468 1,824,411 26 Supply by Source ccf mgd af % San Francisco RWS 65,134,913 133.48 149,529 66.7% Groundwater 9,459,252 19.38 21,715 9.7% Surface -

Sea Scout Support Committee Sunday, January 15 at 2:00 Pm Lucie Stern Community Center, Palo Alto

January 2012 Volume 35, No 4 newsletter of the palo alto historical association General Meeting • Free and Open to the Public • refreshments served Speaker: Josh Gilliland Member of the National Sea Scout Support Committee Sunday, January 15 at 2:00 pm Lucie Stern Community Center, Palo Alto Sea Scout Centennial Patch. (Courtesy Sea Scouts) Sea Scout 100 2012 is the time to celebrate the Centennial of Sea Scouts. Arthur Carey, with the Boy Scout Ship Pioneer in Boston, is credited with starting Sea Scouts in the United States. Today, the Pacific Skyline Council has one of the most active Sea Scout Squadrons in the country and hosts almost all of the major Sea Scout events in Northern California. Josh Gilliland will describe the state of Sea Scouts today and its program opportunities, highlight events from its past hundred years, and provide an overview of Sea Scout Centennial Events in the Bay Area. He is a Cali- fornia attorney, e-Discovery blogger, iPad App Developer, and long-time devotee of Sea Scouts. His ongoing commitment to sea scouting is demon- strated in his chairing the Ancient Mariner Regatta and co-chairing the Safety @ Sea Weekend. a Speaker: Joshua Gilliland, Member of the National Sea Scout Support Committe in uniform aboard the USS Iowa. (Courtesy of J. Gilliland) Oral Histories Palo Alto's First Post Office Building Flood Control in South Palo Alto Oral histories are an invaluable method The Post Office building on Hamilton is one of Palo In this January issue of Tall Tree, it seems relevant to consider rain and floods. -

South County Stormwater Resource Plan

2020 South Santa Clara County Stormwater Resource Plan Prepared By: Watershed Stewardship and Planning Division Environmental Planning Unit South Santa Clara County Stormwater Resource Plan January 2020 Prepared by: Valley Water Environmental Planning Unit 247 Elisabeth Wilkinson Contributors: Kirsten Struve James Downing Kylie Kammerer George Cook Neeta Bijoor Brian Mendenhall Tanya Carothers (City of Morgan Hill/City of Gilroy) Sarah Mansergh (City of Gilroy) Vanessa Marcadejas (County of Santa Clara) Julianna Martin (County of Santa Clara) Funding provided by the Safe, Clean Water and Natural Flood Protection Program i Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................................2 1.1 Background and Purpose .................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Previous and Current Planning Efforts ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 2: South Santa Clara County Watershed Identification ...........................................................5 2.1 Watersheds and Subwatersheds ........................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Internal Boundaries .......................................................................................................................... -

Northern Calfornia Water Districts & Water Supply Sources

WHERE DOES OUR WATER COME FROM? Quincy Corning k F k N F , M R , r R e er th th a a Magalia e Fe F FEATHER RIVER NORTH FORK Shasta Lake STATE WATER PROJECT Chico Orland Paradise k F S , FEATHER RIVER MIDDLE FORK R r STATE WATER PROJECT e Sacramento River th a e F Tehama-Colusa Canal Durham Folsom Lake LAKE OROVILLE American River N Yuba R STATE WATER PROJECT San Joaquin R. Contra Costa Canal JACKSON MEADOW RES. New Melones Lake LAKE PILLSBURY Yuba Co. W.A. Marin M.W.D. Willows Old River Stanislaus R North Marin W.D. Oroville Sonoma Co. W.A. NEW BULLARDS BAR RES. Ukiah P.U. Yuba Co. W.A. Madera Canal Delta-Mendota Canal Millerton Lake Fort Bragg Palermo YUBA CO. W.A Kern River Yuba River San Luis Reservoir Jackson Meadows and Willits New Bullards Bar Reservoirs LAKE SPAULDING k Placer Co. W.A. F MIDDLE FORK YUBA RIVER TRUCKEE-DONNER P.U.D E Gridley Nevada I.D. , Nevada I.D. Groundwater Friant-Kern Canal R n ia ss u R Central Valley R ba Project Yu Nevada City LAKE MENDOCINO FEATHER RIVER BEAR RIVER Marin M.W.D. TEHAMA-COLUSA CANAL STATE WATER PROJECT YUBA RIVER Nevada I.D. Fk The Central Valley Project has been founded by the U.S. Bureau of North Marin W.D. CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT , N Yuba Co. W.A. Grass Valley n R Reclamation in 1935 to manage the water of the Sacramento and Sonoma Co. W.A. ica mer Ukiah P.U. -

We Are Working in Your Neighborhood Creeks! We Are Working in Your

PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE PAID SAN JOSE, CA We are working in your neighborhood creeks! 5750 Almaden Expressway Permit No. 1231 San Jose, CA 95118-3614 www.valleywater.org STREAM MAINTENANCE PROGRAM Before Erosion Repair After Erosion Repair YOUR INVESTMENT AT WORK In November 2012, the voters of Santa Clara County overwhelmingly approved Measure B, the Safe, Clean Water and Natural Flood Protection Program, as a countywide special parcel tax. The 15-year plan’s five priorities are to: Ensure a safe, reliable water supply for the future. As part of its Stream Maintenance Program (SMP), the Santa Reduce toxins, hazards and contaminants, such as Clara Valley Water District plans to perform work along mercury and pharmaceuticals, in our waterways. creeks across Santa Clara County in 2018. Under the SMP, Protect our water supply and local dams from the work occurs annually to improve the environment, reduce the impacts of earthquakes and natural disasters. risk of flooding and keep our communities safe. Restore fish, bird and wildlife habitat and provide open We are working in your neighborhood creeks! For decades, our crews have been trekking into streams space access. to remove sediment build-up, manage vegetation, clear Provide flood protection to homes, businesses, schools, trash and debris, and stabilize banks that have eroded streets and highways. TYPES OF STREAM MAINTENANCE PROGRAM WORK during high flows. The SMP ensures streams with completed flood protection projects continue to function as designed Bank protection and water quality. Invasive plants can increase the risk of flooding and to protect homes and businesses. The water district owns Priority D provides funding for the water district to conduct High and/or sustained flows can cause extensive damage to creek fire danger, undermine structural assets and obstruct access to roads, and manages about 275 miles of streams. -

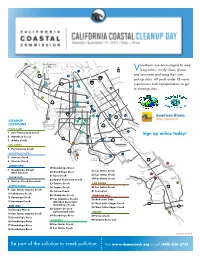

Be Part of the Sollution to Creek Pollution. Visit Or Call (408) 630-2739 PRESENTED BY: Creek Connections Action Group DONORS

1 San Francisco Bay Alviso Milpitas olunteers are encouraged to wear CREEK ty 2 STEVENS si r CR e iv Palo SAN FRANCISQUITO long pants, sturdy shoes, gloves n E 13 U T N Alto 3 N E V A P l N Mountain View i m A e d a M G R U m E A and sunscreen and bring their own C P 7 D O s o MATADERO CREEK A Y era n L O T av t Car U E al Shoreline i L‘Avenida bb C ean P K E EE R a C d C SA l R S pick-up sticks. All youth under 18 need i E R RY I V BER h t E E r R a E o F 6 K o t M s K o F EE t g CR h i IA i n r C supervision and transportation to get l s N l e 5 t E Ce T R t n 9 S I t tra 10 t N e l E ADOBE CREEK P 22 o Great America Great C M a to cleanup sites. p i to Central l e Exp Ke Mc W e h s c s i r t a n e e e k m r El C w c a o 15 4 o o m w in T R B o a K L n in SI a Santa Clara g um LV S Al ER C Sunnyvale R 12 16 E E K 11 ry Homestead 17 Sto S y T a l H n e i 18 O F K M e Stevens Creek li 19 P p S e O O y yll N N ll I u uT l C U T l i R Q h A t R 23 26 C S o Cupertino 33 20 A S o ga O o M T F t Hamilton A a O a G rba z r Ye B T u 14 S e 8 a n n d n O a R S L a 24 A N i A 32 e S d CLEANUP 34 i D r M S SI e L K e V o n E E R E Campbell C n t M R R 31 e E E C t K e r STEVENS CREEK LOCATIONS r S Campbell e y RESERVOIR A Z W I m San L e D v K A CA A E o S E T r TE R e V C B c ly ENS el A s Jose H PALO ALTO L C A a B C a HELLYER 28 m y 30 xp w 1 San Francisquito Creek d Capitol E PARK o r e t e n Saratoga Saratoga i t Sign up online today! u s e Q h 21 C YO c O T 2 Matadero Creek E n i C W R E ARATOGA CR E S 29 K 3 Adobe Creek VASONA RESERVOIR -

Barron Park Association Newsletter

WINTER 2015 BARRON PARK ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE DIWALI REPORT Markus Fromherz, BPA President by Markus Fromherz ou have in front of you n If you have volunteered before, join the another newsletter full board! Your voice and your expertise are of interesting informa- nowhere as impactful for the community Ytion about Barron Park. 2015 as on the BPA board. If you have an impor- has been a year of growth for tant issue you would like to champion, we the BPA, with several new board members, are always open for your ideas and con- new kinds of events for the community, cerns. Or join if you just want to participate and new and increasing activities around on a fun and productive board. development and environmental issues. Think about it and take action before you Just consider the recent Diwali celebra- set this newsletter aside! Send me an email tion (our latest cultural diversity event) or if you can help. the city council decision on facilities with I hope you participated in the recent BPA Dear Jaya and most excellent hazardous materials (an issue that the BPA Meet and Learn survey. We had three suc- team of volunteers, regularly participated in over the years) or cessful Meet and Learn events in 2015 and the recent planting along the Bol Park path asked for your favorite topics for future On behalf of the BPA Board, I’d like to (for which the BPA even formed a commit- events. We got great responses from fifty congratulate and thank you for a fantastic tee this year).