Notes on Survival, Despite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Between Music

Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress 7 Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Of Essence and Context Between Music and Philosophy Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress Volume 7 Series Editor Dario Martinelli, Faculty of Creative Industries, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania [email protected] The series originates from the need to create a more proactive platform in the form of monographs and edited volumes in thematic collections, to discuss the current crisis of the humanities and its possible solutions, in a spirit that should be both critical and self-critical. “Numanities” (New Humanities) aim to unify the various approaches and potentials of the humanities in the context, dynamics and problems of current societies, and in the attempt to overcome the crisis. The series is intended to target an academic audience interested in the following areas: – Traditional fields of humanities whose research paths are focused on issues of current concern; – New fields of humanities emerged to meet the demands of societal changes; – Multi/Inter/Cross/Transdisciplinary dialogues between humanities and social and/or natural sciences; – Humanities “in disguise”, that is, those fields (currently belonging to other spheres), that remain rooted in a humanistic vision of the world; – Forms of investigations and reflections, in which the humanities monitor and critically assess their scientific status and social condition; – Forms of research animated by creative and innovative humanities-based -

Dinosaurs Under Heat

Dinosaurs Under Heat A Written Creative Work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of ^ ^ the requirements for the Degree Jol(, Master of Fine Arts * 'XQ 6 4 ' 111 Creative Writing by Randall Jong San Francisco, California May 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Dinosaurs Under Heat by Randall Jong, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master in Fine Arts Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Michelle Carter, Professor Maxine Chemoff, Professor II Dinosaurs Under Heat Randall Jong San Francisco, California 2016 After four years in the program, 1 have written a short story collection that ruminates around the themes of identity, race, and family structures. 1 am a Chinese American who grew up in San Francisco. I grew up on American pop culture, the English language, and an unfathomable amount of multiple cultures that is truly difficult to generalize. These stories really ask the question: Under certain guises, what does it mean to be an American? I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. -£~'~ t - f — 3 it / Chair, Thesis Committee Date III PREFACE AND/OR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to all my friends, family, faculty, and fellow writers for your support. It’s been a rough few years regarding creativity, but everyone in my life has been truly generous with their encouragement. IV TABLE OF CONTENTS You Wish You Were White......................................................................................................1 The Closest Attempt to Time Traveling................................................................................ -

An Investigation of Jandek's

THEMATIC INTERCONNECTIVITY AS AN INNATE MUSICAL QUALITY: AN INVESTIGATION OF JANDEK’S “EUROPEAN JEWEL” GUITAR RIFFS NICOLE A MARCHESSEAU A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2014 © NICOLE A MARCHESSEAU, 2014 Abstract This dissertation is divided into two main areas. The first of these explores Jandek-related discourse and contextualizes the project. Also discussed is the interconnectivity that runs through the project through the self-citation of various lyrical, visual, and musical themes. The second main component of this dissertation explores one of these musical themes in detail: the guitar riffs heard in the “European Jewel” song-set and the transmigration/migration of the riff material used in the song to other non-“European Jewel” tracks. Jandek is often described in related discourse as an “outsider musician.” A significant point of discussion in the first area of this dissertation is the outsider music genre as it relates to Jandek. In part, this dissertation responds to an article by Martin James and Mitzi Waltz which was printed in the periodical Popular Music where it was suggested that the marketing of a musician as an outsider risks diminishing the “innate qualities” of the so-called outsider musicians’ works.1 While the outsider label is in itself problematic—this is discussed at length in Chapter Two—the analysis which comprises the second half of this dissertation delves into self- citation and thematic interconnection as innate qualities within the project. -

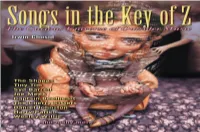

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

Spill the Beans Worship and Learning Resources for All Ages

issue 1 (part 1) pentecost 2a 4 september 2011 to 16 october 2011 spill the beans worship and learning resources for all ages community is... A lectionary-based resource with a Scottish flavour for Sunday Schools, Junior Churches and spillbeans.org.uk Worship Leaders 2011 Spill the Beans Resource Team pentecost 2a 2011 1 ethos statement ethos There is a particular ethos behind this Then each activity is simply a way to in the Bible? Stories don’t exist on their material: it’s all about story. When we spill engage the story and enable children own but in a diverse web, each feeding the the beans about anything, we tell the story and adults to imbed the story, capturing other. different aspects of it, highlighting of what happened and we share the story We believe that as we grow we reflect different images that help us hold the of what that means for us. in different ways on the faith stories we story in our beings. We believe story is the lifeblood of faith. hold. Our idea is to invest these stories In story we can tell the truth and speak But we believe these faith stories ought in people, offering each as a gift of faith. with honesty about things for which there to be able to mingle with our own life The story may be understood in a literal are not yet words. Story contains mystery stories, our day-to-day experiences. So as way during younger years, then with and is the poetry that forms faith. -

Senate Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 2019 No. 156 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was Ms. MCSALLY thereupon assumed ican policy victories and keep our called to order by the Honorable MAR- the Chair as Acting President pro tem- North American neighbors close while THA MCSALLY, a Senator from the pore. we tackle other challenges, such as State of Arizona. f China. f Here we are, months after all three RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME countries’ leaders signed the agree- PRAYER The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- ment, and we are still waiting on the The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- pore. Under the previous order, the House Democrats to let it move for- fered the following prayer: leadership time is reserved. ward. Mexico has already passed it, and Canada is waiting on our move. The Let us pray. f Eternal Father, inspire our law- Senate is ready and eager to ratify it, makers to commit to accomplishing CONCLUSION OF MORNING but the Senate can’t go first. The clock Your purposes in our Nation and world. BUSINESS is ticking. As they seek Your wisdom, teach them The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- Month after month, even as the Your precepts and direct their steps. pore. Morning business is closed. House Democrats have continually May they live lives of obedience and made vague statements that they sup- f abundance as they follow where You port the USMCA and want to see it lead. -

Notes on Survival, Despite JASON HARRIS Bachelor of Arts in English

notes on survival, despite JASON HARRIS Bachelor of Arts in English Marshall University May 2014 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY August 2018 We hereby approve this thesis for JASON HARRIS Candidate for the Master’s Degree in English For the Department of English And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by Caryl Pagel Department & Date Julie Burrell Department & Date Ted Lardner Department & Date Student’s Date of Defense: August 22, 2018 DEDICATION to my mother who remains heaven & sky break of light the way forward always ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All my gratitude and thanks to the family, friends, and readers who have provided me encouragement and support throughout each of these poems; to my best friend, first reader, and more, Autumn Smith; to one of my closest friends and first readers of almost every poem that I write, Kevin Latimer; to the entire staff at BARNHOUSE Journal; to the entire staff at Long Long Journal; to William Lennon and Cleveland Review of Books; to Caryl Pagel for her guidance, feedback, and general excitement for the growth of my writing; to Krysia Orlowski for her early support and encouragement to push my writing to the next level; to Dr. William Breeze for seeing in my potential as scholar and student; to Sheila McMullin for her friendship and emotional support; to Ayesha Khanom for believing in me before I believed in myself; to Kassandra Machado for returning and being a friend, despite. Thank you to the -

Jam338.Pdf (826.6Kb)

FROM HUNGERS TO APPETITES: WOMEN WRITERS AFTER THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Julie Mann Lind May 2013 ©2013JulieMannLind FROM HUNGERS TO APPETITES: WOMEN WRITERS AFTER THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR Julie Mann Lind Cornell University 2013 My dissertation reveals a feminist discourse in texts written by Spanish women who use hunger and appetite as literary tropes after the post Civil War Hunger Years. I argue that the symbolic employment of hunger and appetite allows women writers to find feminism within traditional feminine identities. Drawing attention to the food women cook for others, particularly in their role as mothers, these authors ask us to question the hungers of women themselves. Once they identify various feminine hungers, they begin to explore the emergence of appetite. The emergence of appetite from a condition of hunger is where, I argue, a feminist impulse is manifest. I frame my study in the symbolic connotations of hunger and appetite in the writing of two Spanish women grouped with the Generation of ’27, Rosa Chacel and María Zambrano. In Chacel’s diaries and Zambrano’s philosophical essays, they reveal the tensions that form as women struggle to give their bodies the artistic and intellectual nourishment that they need in the first decades of the Franco regime. They also show that when a woman engages with appetite, a natural desire to explore the world or, as Chacel says, to say “yes” to everything, she is more connected to herself, to art, to knowledge and to others. -

History, Politics, and Religion in the Life and Compositions of Sahba

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 3-6-2019 History, Politics, and Religion in the Life and Compositions of Sahba Aminikia Sinella Aghasi Moshabad Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Aghasi Moshabad, Sinella, "History, Politics, and Religion in the Life and Compositions of Sahba Aminikia" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4815. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4815 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HISTORY, POLITICS, AND RELIGION IN THE LIFE AND COMPOSITIONS OF SAHBA AMINIKIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate FaCulty of the Louisiana State University and AgriCultural and MeChaniCal College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of MusiCal Arts in The SChool of MusiC by Sinella Aghasi Moshabad B.M., California State University Stanislaus, 2014 MM., San FrancisCo State University, 2016 May 2019 To my parents, who sacriFiced their own dreams to make mine come true ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreCiation to my violin professor and committee Chair, Professor Espen Lilleslåtten, who has supported me tremendously and inspired me to beCome a better person as well as a better musiCian. You have taught me to be humble, patient, and most importantly at peaCe through the storms of life.