Learnpress Page :: PDF Output

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Necessity

FORT NECESSITY Washington NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD SITE PENNSYLVANIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF French and English Rivalry Virginians under Colonel Joshua Fry proceeded Virginians and Indians started for the camp of THE INTERIOR: Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary westward from Virginia toward Monongahela. Jumonville, the French commander, which was National Park Service, Arthur E. Demaray, Director Rival claims between the French and English Washington, then a lieutenant colonel, was sec situated about 2 miles to the northward. to the trans-Allegheny territory approached a ond in command. While Fry remained at Wills Jumonville was taken by surprise. Ten of his men were killed; one wounded. Jumonville was among those killed. Twenty-one survivors were made prisoners, one man escaping to carry the news to the French at Fort Duquesne. In Wash ington's command only one man was killed and Fort two wounded. The man who was killed was buried on the spot. Surrender of Fort Necessity Mount Washington Tavern, located a few Old tollgate house built in 1814 on Old National Pike, a hundred feet from the site of Fort Necessity few miles east of Fort Necessity After the Jumonville fight, Washington Necessity undertook to fortify his position at Great The month of June was spent in opening a fort and began the attack. The fighting, which Meadows. He built a palisade fort during the road from Fort Necessity to a clearing in the began about 11 o'clock in the morning, con last 2 days of May and the first day of June. forest, known as Gist's Plantation, in the direc tinued sporadically until about 8 o'clock at National Battlefield Site In his journal entry for June 25, Washington tion of the forks of the Ohio. -

Elim Plantation the Fry Family Built Their Home in What Was Then Orange, Or Perhaps Culpeper County Virginia

Elim Plantation The Fry family built their home in what was then Orange, or perhaps Culpeper county Virginia. The Biblical Elim was an oasis in the desert, a place where God showed his compassion to the thirsty refugees traveling out of Egypt, toward the Promised Land. Today Elim operates as an upscale Virginia Wine Country Bed and Breakfast - The Inn at Meander Plantation. Two plantations are attributed to Joshua Fry in the beautiful countryside surrounding the city of Charlottesville Virginia. Elim, located near the community of Locust Dale is about thirty-five miles north and east of Charlottesville. Viewmont is ten miles south of Charlottesville. Viewmont was probably built and occupied by the Joshua Fry family about 1744, when they moved west from Essex county Virginia to Albemarle County Virginia. Elim was constructed sometime between 1745 and 1766. Opinions differ on whether it was the home of Joshua Fry, or his son Henry Fry (my 5x great-grandfather). Henry Fry was married to Susan “Sukey” Walker in 1764, and Elim was the home where they raised their large family. The home remained in the hands of descendants (the Lightfoot family) into the early 1900s. The plantation was patented in 1726 by Col. Joshua Fry, a member of the House of Burgesses and professor at William and Mary. Col. Fry and his partner Peter Jefferson, father of Thomas Jefferson, surveyed and drew the first official map of the area known as Virginia. Fry commanded the Virginia Militia at the start of the French and Indian War, with George Washington as his second in command. -

The Ironworking Pennybackers of Shenandoah County, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 Down the Great Wagon Road: The Ironworking Pennybackers of Shenandoah County, Virginia Sarah Elaine Thomas College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Thomas, Sarah Elaine, "Down the Great Wagon Road: The Ironworking Pennybackers of Shenandoah County, Virginia" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626692. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-vqqr-by31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Down The Great Wagon Road: The Ironworking Pennybackers of Shenandoah County, Virginia Sarah Elaine Thomas Front Royal, Virginia Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2010 Bachelor of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2012 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts w -t-v: Sarah Elaine Thomas Approved by the Committee, February, 2012 Committee Chai Pullen Professor James P. Whittenburg ry The College of William & Mary Visiting Assistant Professor SusarvA. Kern, History The College of William & Mary Assistant Professor James D. -

Marion County, Tennessee Many Coming Into Western North Carolina Through in the Beginning Watauga, Swannonoa, and Butt Mountain Gaps

Marion Co., Tennessee – Cherokee Territory Submitted by Nomie Webb Hundreds of settlers moved through mountain gaps, Marion County, Tennessee many coming into Western North Carolina through In the Beginning Watauga, Swannonoa, and Butt Mountain Gaps. ~ Once upon a time, the area of Tennessee was The Great Wagon Road covered by a great inland sea. During a series of to the Carolina frontier. cataclysmic upheavals, giant folds (like an accordion) Early settlers used rose and the sea drained. The draining sea left a wide these routes to reach fertile basin, and the folds became known as the Great western North Carolina. Smoky and Cumberland Mountains. As a lush forest sprang from the basin, soil and groups of Indians settled here. In the 1700s four or five Indian tribes inhabited this area and by then this region belonged to the British Colony of North Carolina. New immigrants to America looking for new lands to settle, began forming groups to penetrate these vast open lands, but the Blue Ridge Mountains were barriers to travel. For that reason it was easier for the new settlers to come into the area of (now) The early settlers crossed the mountains and moved Tennessee from the north than from the east. Many of into the Great Appalachian Valley. these early settlers, therefore came from Virginia, or “overland”, by way of the Kentucky route. Starting as early as 1768 several families came in To the north east corner of this area from the Uplands of North Carolina. They banded together as the Watauga Association in 1771 and spread over the eastern part Of the section. -

Joshua Fry in Excerpts from the Rose

Joshua Fry in excepts from the Rose Diary 1746-1751 compiled and edited by Aubin Clarkson Hutchison, 1999 updated by Pamela Hutchison Garrett, February 2015 The Diary of Robert Rose, 1746-1751, was edited by the Rev. Ralph E. Fall of Port Royal, VA, who worked on the volume for twelve years. It adds considerable color to our story of Col. Joshua Fry. Rev. Fall served at historic Vaughter’s Church in Essex County, St. Asaph’s in Bowling Green, and St. Peter’s in Port Royal, VA. His wife, Elizabeth Stambaugh Fall, a Rose descendant, designed the dust jacket for the book. Murray Fontaine Rose of Falls Church, VA, a seventh-generation descendant of Parson Robert Rose, produced the map which accompanies the volume. It is unique in that authentic records for several hundred plantations, towns, and other sites were used to plot locations on present-day topography by the U.S. Geological Survey. The Rev. Robert Rose was born in Wester Alves, Scotland on 12 Feb 1704. He was minister of St. Anne's Parish, Essex County, Va., 1727-1748, and of St. Anne's Parish, Albemarle County, Va., 1748-1751. He was in Essex Co, VA when Vaughter’s Church was erected in 1731, where services still continue to this day. This is the Church where the body of our ancestor Dr. Paul Micou was reburied in 1966. Probably it was in Essex County that young parson Rose and Joshua Fry first became fast friends. A synopsis of the Diary, given at the Colonial Williamsburg website, highlights, “The diary reveals Rose as a planter, businessman, surveyor, doctor, and lawyer, as well as a minister and a frequent traveler between Albemarle and Essex counties. -

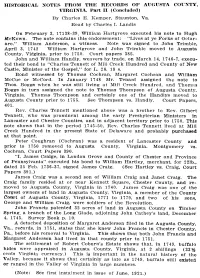

HISTORICAL NOTES from the RECORDS of AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, Part II (Concluded) by Charles E

HISTORICAL NOTES FROM THE RECORDS OF AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, Part II (Concluded) By Charles E. Kemper, Staunton, Va. Read by Charles I. Landis On February 3, 17138-39, William Hartgrove executed his note to Hugh McKown. The note contains this endorsement: "Lives at ye Forks of Octar- aro." William Anderson, a witness. Note was signed to John Trimble, April 3, 1742 William Hartgrove and John Trimble moved to Augusta County, Virginia, prior to 1750. Court papers 385. John and William Handly, weavers by trade, on March 14, 1746-7, execu- ted their bond to "Charles Tennett of Mill Creek Hundred and County of New Castle, Minister of the Gospel," for L. 26, 18 s. Bond witnessed by Thomas Cochran, Margaret Cochran and William McCue or McCord. In January 1748 Mr. Tenant assigned the note to Thos. Boggs when he was still living at Mill Creek Hundred, and Thomas Boggs in turn assigned the note to Thomas Thompson of Augusta County, Virginia. Thomas Thompson and certainly one of the Handlys moved to Augusta County prior to 1755. See Thompson vs. Handly. Court Papers, 401. Rev. Charles Tennett mentioned above was a brother to Rev. Gilbert Tennett, who was prominent among the early Presbyterian Ministers in Lancaster and Chester Counties, and in adjacent territory prior to 1750. This note shows that in the period 1745-50, Rev. Charles Tennett lived at Mill Creek Hundred in the present State of Delaware and probably purchased at that point. Peter Coughran (Cochran) was a resident of Lancaster County and prior to 1750 removed to Augusta County, Virginia. -

Jumonville Glen

obscure place." Did Jumonville hope to spy on Washington and report back to Contrecouer about the JUMONVILLE GLEN On May 28, 1754, a small group of Virginians, under the English strength and then make contact, or possibly command of 22-year-old George Washington, attacked even attack as Washington had feared? On the other a French patrol at what is now known as Jumonville hand, if Jumonville was on a military patrol rather than a Glen. Although only a few men became casualties, this diplomatic mission, why did he, an experienced officer, 15-minute skirmish deep in the North American wilder allow himself to be completely surprised at breakfast? ness was the first in a series of major events that even Washington's actions have also been questioned by tually plunged most of the western world into warfare. historians. If the French had in fact been merely Horace Walpole, a contemporary British statesman, diplomats, he was guilty of shooting down men who described the brief fight by saying, "A volley fired by a were only doing what Washington himself had done the young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the previous year at Fort LeBouef. This skirmish was the world on fire." first in Washington's career and he could not possibly help but be eager for success. He was also tired, having had little sleep in the previous 48 hours. Under these cir cumstances, his decision-making capability may have been hampered. It is possible only to speculate on the true answer. Nonetheless, dire consequences of both Jumonville's and Washington's actions at Jumonville Glen, as it is known today, soon followed. -

NCSS Theme: People, Places, and Environment 2Nd Nine Weeks Lesson 2: the Great Wagon Road- Part 1 Question for Exploration

NCSS Theme: People, Places, and Environment 2nd Nine Weeks Lesson 2: The Great Wagon Road- Part 1 Question for Exploration: How has geography influenced how my town has grown? Local Connection-brief description: Students will identify the physical features settlers would have encountered while traveling on The Wilderness Road and The Great Wagon Road. They will interpret whether those features may have helped or hindered their progress? Key vocabulary: migration, obstacles, physical features Historical Primary Sources Additional Materials/Resources Local: Copies of a physical map of the United States National: (Library of Congress) Reference: Virginia’s Montgomery County, Mary Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia, 1751, Elizabeth Lindon, Editor – pp 163-166 showing the Great Wagon Road DIGITAL ID g3880 ct000370 Curriculum Connections: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3880.ct000370 Writing a paragraph 4th grade Virginia Studies-Cumberland Gap Key Knowledge Key Skills and Processes The Great Wagon Road led settlers from Analyze and interpret maps to explain Pennsylvania to Georgia. North of Roanoke (Big relationships among landforms, water features, Lick) the road branched to the west and crossed and historical events. the Cumberland Gap taking settlers to Kentucky and Tennessee. It led German and Scots-Irish settlers south to the fertile land west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. This westward stretch of road which led settlers into the wilderness and to Kentucky is often referred to as the Wilderness Road. This path was a major route for westward migration between 1790 and 1840. Products and Evidence of Understanding/Assessment (How will I know they know?) Exit slip describing route and travel for settlers migrating south and west. -

An Educator's Guide to the Story of North Carolina

Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide An Educator’s Guide to The Story of North Carolina An exhibition content guide for teachers covering the major themes and subject areas of the museum’s exhibition The Story of North Carolina. Use this guide to help create lesson plans, plan a field trip, and generate pre- and post-visit activities. This guide contains recommended lessons by the UNC Civic Education Consortium (available at http://database.civics.unc.edu/), inquiries aligned to the C3 Framework for Social Studies, and links to related primary sources available in the Library of Congress. Updated Fall 2016 1 Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide The earth was formed about 4,500 million years (4.5 billion years) ago. The landmass under North Carolina began to form about 1,700 million years ago, and has been in constant change ever since. Continents broke apart, merged, then drifted apart again. After North Carolina found its present place on the eastern coast of North America, the global climate warmed and cooled many times. The first single-celled life-forms appeared as early as 3,800 million years ago. As life-forms grew more complex, they diversified. Plants and animals became distinct. Gradually life crept out from the oceans and took over the land. The ancestors of humans began to walk upright only a few million years ago, and our species, Homo sapiens, emerged only about 120,000 years ago. The first humans arrived in North Carolina approximately 14,000 years ago—and continued the process of environmental change through hunting, agriculture, and eventually development. -

The Great Wagon Road of the Carolinas

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1974 The Great Wagon Road of the Carolinas Richard George Remer College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Remer, Richard George, "The Great Wagon Road of the Carolinas" (1974). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624870. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-w0y7-0655 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GREAT WAGON ROAD OF THE CAROLIRAS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Richard George Reiner 1974 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts HcUU 'Author Approved, August 1974 / f ? > O Q Richard Maxwell Brown . - „ v Edward M. Riley/ James Thompson sos^s TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...................................... iv LIST OF M A P S ........................................... v ABSTRACT ............................................... vi INTRODUCTION ........................................ -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Carte De La Virginie Et Du Maryland Dressee sur la grande carte Angloise de Mrs. Josue Fry et Pierre Jefferson . 1755 Stock#: 40186 Map Maker: de Vaugondy Date: 1780 circa Place: Paris Color: Outline Color Condition: VG+ Size: 25.5 x 19 inches Price: SOLD Description: Nice example of the single sheet version of the seminal Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia and Maryland, engraved by Elisabeth Haussard and published in Paris by Robert De Vaugondy for the Atlas Universel. A well executed reduction of Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson's landmark, which was originally issued separately and later appeared in Jefferys' American Atlas. The result is a beautiful single folio sheet example of the most sought after and recognizable 18th Century map of Virginia and Maryland. While the title is in French, virtually all of the place names and annotations are in English. The map provides a fabulously detailed look into pre-revolutionary war Virginia and Maryland, extending west to the Alleghany Mountains, and including Delaware and a portion of New Jersey, as well as the region around Philadelphia. Originally prepared by Joshua Fry of William & Mary and Peter Jefferson (father of President Thomas Jefferson) at the request of Lord Halifax in 1748, the Fry-Jefferson was a monumental leap forward in the mapping of the region. It is the first map to accurately depict the Blue Ridge Mountains and the first to lay down the colonial road system of Virginia. -

The Great Valley Road

The Great Valley Road ~ Traffic ~ ~ Features ~ German settlers in the Shenandoah Valley kept to themselves The road began as a buffalo trail, and was followed by so much that other settlers seldom saw them. They clustered Indians as the Great Warrior Path from New York to the in farms close to their church and school. They ventured into Carolinas. At Salisbury, NC, it was joined by their Great the towns of New Market, Luray, Woodstock, or Harrison- Trading Path. burg only to trade. About 57 percent of the population of Shenandoah and Rockingham Counties and about 33 percent As a road for pioneer settlers, it bore many names. Since in Page and Frederick counties were of German stock. the road progressed through the Shenandoah Valley, it The Scots-Irish, driven from their Ulster homeland by drought came to be called both the Great Valley Road and the in 1717, found opportunity in America. By 1729 they came Shenandoah Valley Road. The link by the early 1740s in large numbers. Entire families "bumped over the Philadel- from the Pennsylvania communities of Lancaster, York, phia road in big-wheeled Conestoga wagons, trailing cattle and Gettysburg became known as the Philadelphia Wagon and dogs. Nearly all were Presbyterians, once employed in Road. This portion was also referred to as the Lancaster the Irish linen and wool trades. Half were so poor that they Pike, and its 63 miles was the most heavily traveled portion indentured themselves to obtain passage. By-passing the of the entire road. Another link, by 1746, was the Pio- Germans, the Scots-Irish settled in numbers in Augusta, neer's Road from Alexandria to Winchester.