Kanchanaburi and the Thai-Burma Railway: Disputed Narratives in the Interpretation of War Lennon, John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zootaxa,Namtokocoris Sites, a New Genus of Naucoridae

Zootaxa 1588: 1–29 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Namtokocoris Sites, a new genus of Naucoridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) in waterfalls of Indochina, with descriptions of six new species ROBERT W. SITES AND AKEKAWAT VITHEEPRADIT Enns Entomology Museum, Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA Abstract A new genus with six new species of Naucoridae inhabiting waterfalls of Indochina are described from a decade of aquatic insect collections in Thailand and Vietnam. Namtokocoris Sites NEW GENUS is diagnosed by a pair of promi- nent scutellar protuberances, the prosternal midline bears an expansive, thin, plate-like carina, the forelegs of both sexes have a one-segmented tarsus apparently fused with the tibia, and a single claw. Prominent linear series of stout hairs occur on the hemelytra, although this attribute is not unique within the subfamily. Despite the lack of sexual dimorphism in the forelegs, this new genus is a member of the subfamily Laccocorinae, an assignment based on other characters con- sistent with this subfamily. Character states of this genus are compared with those of other Asian genera of Laccocori- nae. The type species, Namtokocoris siamensis Sites NEW SPECIES, is widely distributed from northern through eastern Thailand in waterfalls of several mountain ranges. Namtokocoris khlonglan Sites NEW SPECIES was collected only at Namtok Khlong Lan at Khlong Lan National Park. Namtokocoris minor Sites NEW SPECIES was collected at two waterfalls near the border with Burma in Kanchanaburi Province and is the smallest species known. -

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation Due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No. 1/2564 Re : COVID-19 Zoning Areas Categorised as Maximum COVID-19 Control Zones based on Regulations Issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005) ------------------------------------ Pursuant to the Declaration of an Emergency Situation in all areas of the Kingdom of Thailand as from 26 March B.E. 2563 (2020) and the subsequent 8th extension of the duration of the enforcement of the Declaration of an Emergency Situation until 15 January B.E. 2564 (2021); In order to efficiently manage and prepare the prevention of a new wave of outbreak of the communicable disease Coronavirus 2019 in accordance with guidelines for the COVID-19 zoning based on Regulations issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005), by virtue of Clause 4 (2) of the Order of the Prime Minister No. 4/2563 on the Appointment of Supervisors, Chief Officials and Competent Officials Responsible for Remedying the Emergency Situation, issued on 25 March B.E. 2563 (2020), and its amendments, the Prime Minister, in the capacity of the Director of the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration, with the advice of the Emergency Operation Center for Medical and Public Health Issues and the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration of the Ministry of Interior, hereby orders Chief Officials responsible for remedying the emergency situation and competent officials to carry out functions in accordance with the measures under the Regulations, for the COVID-19 zoning areas categorised as maximum control zones according to the list of Provinces attached to this Order. -

Nitrate Contamination in Groundwater in Sugarcane Field, Suphan Buri Province, Thailand

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-1S, May 2019 Nitrate Contamination in Groundwater in Sugarcane Field, Suphan Buri Province, Thailand Sorranat Ratchawang, Srilert Chotpantarat - infants and human birth defects [6], [7]. Nitrate (NO3 ) is a Abstract: Due to the intensive agricultural activities, nitrate chemical compound with one part nitrogen and three parts - (NO3 ) contamination is one of the problems for groundwater oxygen. This common form of nitrogen is usually found in resource protection in Thailand, well-known as an agricultural water. In general, occurring concentrations of nitrate in country. Nitrate has no taste and odorless in water and can be detected by chemical test only. It was reported that Suphan Buri is groundwater are naturally less than 2 mg/L originated from considered as one of the provinces with intensive agricultural natural sources such as decaying plant materials, atmospheric - areas, especially sugarcane fields. In this study, NO3 deposition, and inorganic fertilizers. concentrations were measured in 8 groundwater wells located in In Asia, nitrogen fertilizer application has increased - sugarcane fields in this province. NO3 concentration in the area dramatically approximately 17-fold in the last 40 years [8]. was ranged from 2.39 to 68.19 mg/L with an average As comparing to other countries, it was found that average concentration of 30.49 mg/L which was a bit higher than the previous study by Department of Groundwater Resources or fertilizer application rates of Thailand are low (Thailand: 101 - DGR, which found that NO3 was in the range of 0.53-66 mg/L kg/ha; USA: 113 kg/ha; China: 321 kg/ha). -

Despatches Summer 2016 July 2016

Summer 2016 www.gbg-international.com DESPATCHES IN THIS ISSUE: PLUS Battlefield Guide On The River Kwai Verdun 1916 - The Longest Battle The Ardennes and Back Again AND Roman Guides Guide Books 02 | Despatches FIELD guides Our cover image: Dr John Greenacre brushing up on the facts at the Sittang River, Myanmar. Andrew Thomson explaining the Siegfried Line, Hurtgen Forest, Germany German trenches in the Bois d’Apremont, St Mihiel. www.gbg-international.com | 03 Contents P2 FIELD guides P18-20 TESTING THE TESTUDO A Guild project P5-11 HELP FOR HEROES IN THAILAND P21 FIELD guides AND MYANMAR An Opportunity Grasped P22-25 VERDUN The Longest Battle P12-16 A TALE OF TWO TOURS Two different perspectives P25 EVENT guide 2016 P17 FIELD guides P26-27 GUIDE books Under The Devil’s Eye, newly joined Associate Member, Alan Wakefield explaining the intricacies of The Birdcage Line outside Thessaloniki. (Picture StaffRideUK) 04 | Despatches OPENING shot: THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEW Welcome fellow members, Guild Partners, and positive. The cream will rise to the top and those at the Supporters to the Summer 2016 edition of fore of our trade will take those that want to raise their Despatches, the house magazine of the Guild. individual and collective standards with them. These The year so far has been dominated by FWW interesting times offer great opportunities for the commemorative events marking the centenaries of Guild. Our validation programme is an ideal vehicle Jutland, Verdun and the Somme. Recent weeks have for those seeking self-improvement and, coupled with seen the predominantly Australian ceremonies at our shared aims, encourages the raising of collective Fromelles and Pozieres. -

Kanchanaburi Province Holds River Kwai Bridge Festival 2015 (28/11/2015)

Kanchanaburi Province Holds River Kwai Bridge Festival 2015 (28/11/2015) Kanchanaburi Province is organizing the River Kwai Bridge Week, an event to promote tourism and take visitors back to the times of World War II. Both Thai and international tourists are welcome to the River Kwai Bridge Week, also known as the River Kwai Bridge Festival. It is held in conjunction with the Kanchanaburi Red Cross Fair, under the theme \"70 Years of Peace, Peaceful Kanchanaburi. The River Kwai Bridge Week and Kanchanaburi Red Cross Fair 2015 takes place in the River Kwai Bridge area and the Klip Bua field in Mueang district from 28 November to 7 December 2015. The highlight of this event is the spectacular light and sound presentation, telling the history of the River Kwai Bridge and the Death Railway of World War II. The festival also features cultural performances, concerts, exhibitions, a fun fair, and a bazaar of local products. Visitors will learn more about Kanchanaburi, which is the location of monuments associated with World War II. During the war, a large number of Allied prisoners of war and locally conscripted laborers were forced to build the River Kwai Bridge, which was part of the historic \"Death Railway linking Thailand with Burma, presently Myanmar. The Japanese who occupied Thailand at that time demanded free passage to Burma, and they wanted the railway bridge to serve as their supply line between Thailand, Burma, and India. The prisoners of war were from Australia, England, Holland, New Zealand, and the United States. Asian workers were also employed to build the bridge and the railway line, passing through rugged mountains and jungles. -

Hellfire Pass & Kanchanaburi War Cemetery Thailand

Anzac Day 2022 Commemorations Hellfire Pass & Kanchanaburi War Cemetery Thailand Tour Summary Travel to the River Kwai (Thailand) for the Anzac Day Duration: 3 Days, 2 Nights commemorations for what will be an emotional but uplifting From/To: Bangkok experience. Join the deeply moving Dawn Service at Hellfire Pass Departs: 24th April 2022 before attending the Wreath Laying Ceremony at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery later in the morning. Tour type: Join-in/Small group Status: Guaranteed departure Visit the Chungkai War Cemetery and iconic places such as the Bridge over the River Kwai, the spectacular Wang Pho Viaduct and Pricing Details: enjoy a trip on a long-tail boat on the Kwai Rivers and a train ride Twin share - $925 pp on a still operating section of the Burma-Thailand Railway. Single room surcharge - $185 pp All prices are quoted in AUD Prices valid to 28/02/2022 Tour Details Day 1: Saturday, 24th April 2022 Depart hotel: 7:00-7:30am (Bangkok city location) Finish: 3:30pm approx. Depart your Bangkok city hotel for the River Kwai and Kanchanaburi (about 3 hours after leaving Bangkok) and visit the Thailand-Burma Railway Centre, a museum of world renown. Dioramas, artefacts (retrieved from various camps and work sites along the railway) and personal stories of POW’s, all combine to give you a better appreciation of the railway story and put perspective into the sites that you will visit during the rest of the tour. After lunch, visit the Hellfire Pass Interpretive Centre which depicts the construction of the railway through this mountainous Hellfire Pass Memorial section and the hardships that the POW’s had to endure. -

The Water Footprint Assessment of Ethanol Production from Molasses in Kanchanaburi and Supanburi Province of Thailand

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com APCBEE Procedia 5 ( 2013 ) 283 – 287 ICESD 2013: January 19-20, Dubai, UAE The Water Footprint Assessment of Ethanol Production from Molasses in Kanchanaburi and Supanburi Province of Thailand. Chooyok P, Pumijumnog N and Ussawarujikulchai A Faculty of Environment and Resource Studies, Mahidol University, Salaya, Phutthamonthon, Nakhon Pathom 73170, THAILAND. Abstract This study aims to assess water footprint of ethanol production from molasses in Kanchanaburi and Suphanburi Provinces of Thailand, based on the water footprint concept methodology. The water footprint of ethanol from molasses can be calculated into three parts: sugar cane, molasses, and ethanol production. The green, blue, and grey water footprints of ethanol production from molasses in the Kanchanaburi Province are 849.7, 209.6, and 45.0 (m3/ton), respectively, whereas those of ethanol in the Suphanburi Province are 708.3, 102.9, and 64.8 (m3/ton), respectively. Study results depend on several factors such as climate, soil, and planting date. These are related and effective to the size of water footprint. Especially, if schedule of planting and harvest date are different, which causes the volume of rainfall to be different; these affect the size of water footprints. A limitation of calculation of grey water footprint from crop process has been based on a consideration rate of nitrogen only. Both provinces in the study area have their respective amount of the grey water footprint of molasses, and ethanol production is zero. The wastewater in molasses and ethanol production have a very high temperature and BOD, whereas the grey water footprint in this study is zero because the wastewater may be stored in pond, or it may be reused in area of factory and does not have a direct discharge into the water system. -

UNHCR/UNIFEM/UNOHCHR/WB Joint Tsunami Migrant Assistance

TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE MISSION REPORT IOM/ UNHCR/UNIFEM/UNOHCHR/WB Joint Tsunami Migrant Assistance Mission to the Provinces of Krabi, Phangnga, Phuket and Ranong, Thailand 20-25 January 2005 Date of publication: 16 February 2005 Table of Contents Overview............................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary............................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations.......................................................................................... 5 Map of Affected Areas........................................................................................................ 6 I. Size and location of the Tsunami-Affected Migrant Population ............................ 7 a) Total number of migrants in four provinces ....................................................... 7 b) Phangnga Province.............................................................................................. 8 c) Ranong Province............................................................................................... 10 d) Phuket Province ................................................................................................ 11 e) Krabi Province .................................................................................................. 11 II. Effect of Tsunami on Migrant Workers................................................................ 13 a) Death Toll and Injuries -

Military Memorials of National Significance Bill 2008

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library BILLS DIGEST Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 1 May 2008, no. 95, 2007–08, ISSN 1328-8091 Military Memorials of National Significance Bill 2008 Paula Pyburne Law and Bills Digest Section Contents Purpose.............................................................. 2 Background........................................................... 2 The current state of the law .............................................2 Funding of national memorials...........................................3 Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial in Ballarat ..........................4 Can a local memorial be a ‘national memorial’? ............................. 4 Basis of policy commitment.............................................5 The question of funding............................................... 6 Financial implications ................................................... 6 Main provisions........................................................ 7 Concluding comments ................................................... 9 2 Military Memorials of National Significance Bill 2008 Military Memorials of National Significance Bill 2008 Date introduced: 19 March 2008 House: House of Representatives Portfolio: Veterans' Affairs Commencement: On the day on which it receives the Royal Assent Links: The relevant links to the Bill, Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be accessed via BillsNet, which is at http://www.aph.gov.au/bills/. When Bills have -

E&O Fact Sheet.Pub

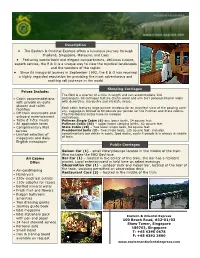

Description • The Eastern & Oriental Express offers a luxurious journey through Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Laos • Featuring comfortable and elegant compartments, delicious cuisine, superb service, the E & O is a unique way to view the mystical landscapes and the wonders of the region • Since its inaugural journey in September 1993, the E & O has received a highly regarded reputation for providing the most adventurous and exciting rail journeys in the world Sleeping Carriages Prices Include: The E&O is a quarter of a mile in length and can accommodate 126 • Cabin accommodations passengers. All carriages feature cherry wood and elm burr paneled interior walls with private en-suite with decorative marquetry and intricate inlays. shower and toilet Each cabin features large picture windows for an excellent view of the passing scen- facilities ery. Luggage is limited to 60 pounds per person for the Pullman and State cabins. • Off train excursions and The Presidential suites have no luggage onboard entertainment restrictions. • Table d’ hôte meals Pullman Single Cabin (6) -one lower berth, 54 square feet • All applicable taxes Pullman Cabin (30) – upper/lower sleeping births, 62 square feet • Complimentary Mail State Cabin (28) – Two lower single beds, 84 square feet service Presidential Suite (2) – Two single beds, 125 square feet. Includes • Limited selection of complimentary bar drinks in cabin, Ipod docks, seats 4 people & is always in middle magazines and daily of train. English newspaper Public Carriages Saloon Car (1) - small library/lounge located in the middle of the train. Also includes the E&O Boutique All Cabins Bar Car (1) – located in the center of the train, the bar has a resident Offer: pianist. -

10040596.Pdf

SOUTHEAST ASIAN J TROP MED PUBLIC HEALTH MONITORING THE THERAPEUTIC EFFICACY OF ANTIMALARIALS AGAINST UNCOMPLICATED FALCIPARUM MALARIA IN THAILAND C Rojanawatsirivej1, S Vijaykadga1, I Amklad1, P Wilairatna2 and S Looareesuwan2 1Malaria Division, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi; 2Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand Abstract. Increasing antimalarial drug-resistance is an important problem in Thailand. The results of monitoring the antimalarial efficacy are used in decision-making about using antimalarials to treat uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand. In 2002, 552 patients with uncomplicated malaria were treated according to the Thai National Drug Policy, with mefloquine 25 mg/kg plus artesunate 12 mg/kg and primaquine 30 mg in divided doses for 2 days in high-mefloquine-resistant areas; mefloquine 15 mg/kg plus primaquine 30 mg in non- or low-mefloquine-resistant areas; mefloquine 15 mg/kg plus artesunate 12 mg/kg and primaquine 30 mg in divided doses for 2 days or Coartem® (6- dose regimen for adult contains 480 mg artemether and 2880 mg lumefantrine) plus primaquine 30 mg given over 3 days in moderate-mefloquine-resistant areas. The study shows that mefloquine, artesunate plus mefloquine, and artemether plus lumefantrine are effective in the treatment of uncom- plicated malaria in most areas of Thailand except for Ranong and Kanchanaburi, where the first-line treatment regimen should be revised. INTRODUCTION falciparum malaria (WHO, 1994; 1997; 2001). The purpose of this study was to ascertain Antimalarial resistance has spread and in- the therapeutic efficacy of first-line treatment for tensified in Thailand over the past 40 years. uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Mae Hong There is now a very high level of drug resistance, Son (MHS), Tak (TK), Kanchanaburi (KB), with evidence both in vitro and in vivo of P. -

A Critique of the Militarisation of Australian History and Culture Thesis: the Case of Anzac Battlefield Tourism

A Critique of the Militarisation of Australian History and Culture Thesis: The Case of Anzac Battlefield Tourism Jim McKay, Centre for Critical and Cultural Studies, University of Queensland This special issue on travel from Australia through a multidisciplinary lens is particularly apposite to the increasing popularity of Anzac battlefield tourism. Consider, for instance, the Dawn Service at Gallipoli in 2015, which will be the highlight of the commemoration of the Anzac Centenary between 2014 and 2018 (Anzac Centenary 2012). Australian battlefield tourism companies are already fully booked for this event, which is forecast to be ‘the largest peacetime gathering of Australians outside of Australia’ (Kelly 2011). Some academics have argued that rising participation in Anzac battlefield tours is symptomatic of a systemic and unrelenting militarisation of Australian history and culture. Historians Marilyn Lake, Mark McKenna and Henry Reynolds are arguably the most prominent proponents of this line of reasoning. According to McKenna: It seems impossible to deny the broader militarisation of our history and culture: the surfeit of jingoistic military histories, the increasing tendency for military displays before football grand finals, the extension of the term Anzac to encompass firefighters and sporting champions, the professionally stage-managed event of the dawn service at Anzac Cove, the burgeoning popularity of battlefield tourism (particularly Gallipoli and the Kokoda Track), the ubiquitous newspaper supplements extolling the virtues of soldiers past and present, and the tendency of the media and both main political parties to view the death of the last World War I veterans as significant national moments. (2007) In the opening passage of their book, What’s Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History (henceforth, WWWA), to which McKenna contributed a chapter, Lake and Reynolds also avowed that militarisation was a pervasive and inexorable PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol.