Making Things in Australia Again? Not in Victoria Bob Birrell and Ernest Healy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision for a Smaller Planet

INFASTRUCTURE Vision for a smaller planet Andrew Gray THE VPELATHE ARG Planning victorianrevue / planning / environmental / law / association / volume 94 March 2015 1 / VPELA Revue March 2015 VPELA Board Members Contents Executive President President 3 Tamara Brezzi Minister 7 T: 8686 6226 Shadow Minister 8 E: [email protected] Editorial 11 Vice President (Planning) News from Planning Panels 12 Jane Monk News from VCAT 14 T: 9651 9678 E: [email protected] Places Vice President (Legal) Urban Renewal Tip Top, Brunswick 15 Adrian Finanzio Rethinking the strip: Bridge Road 19 T: 9225 8745 Medelin, Columbia: changing the game 26 E: [email protected] Traditional activity centres 41 Secretary VPELA UDIA Singapore Tour 46 Michael Deidun The Business T: 9628 9708 E: [email protected] Planning in Victoria 2015? 5 Planning improvements at City of Greater Geelong 9 Treasurer Rory’s Ramble 23 Jane Sharp VCAT seminar 24 T: 9225 7627 Municipal Matters: Accretion 32 E: [email protected] The Fast Lane 37 Executive Director Shining through or Shady? Solar panels and VCAT 38 Jessica Cutting Legal World 43 T: 8392 6383 Seminar Report: Fire and Planning 48 E: [email protected] Planning Xchange 55 Executive Director Julie Reid People T: 8571 5269 Traffic engineering; my way 17 E: [email protected] A day with Susan Brennan QC 21 Under the microscope: Bert Dennis 35 Members Jeff Akehurst 45 Frank Butera T: 9668 5564 New Board members 54 John Carey T: 8608 2687 YPG Jennifer Jones T: 0409 412 141 Mimi Marcus T: 9258 3871 YPG Master Class articles 50 Jillian Smith T: 9651 9542 YPG Bowls Event 52 Natasha Swan T: 0427 309 349 YPG Committee 52 Adam Terrill T: 9429 6133 Con Tsotsoros T: 8392 6402 Christine Wyatt T: 9208 3601 Newsletter editor: Bernard McNamara M: 0418 326 447 E: [email protected] T: 9699 7025 VPELA PO Box 1291 Camberwell 3124 www.vpela.org.au T: 9813 2801 Cover photo: Minister Richard Wynne addressed an enthusiastic crowd at the VPELA Christmas Party. -

Help Save Quality Disability Services in Victoria HACSU MEMBER CAMPAIGNING KIT the Campaign Against Privatisation of Public Disability Services the Campaign So Far

Help save quality disability services in Victoria HACSU MEMBER CAMPAIGNING KIT The campaign against privatisation of public disability services The campaign so far... How can we win a This is where we are up to, but we still have a long way to go • Launched our marginal seats campaign against the • We have been participating in the NDIS Taskforce, Andrews Government. This includes 45,000 targeted active in the Taskforce subcommittees in relation to phone calls to three of Victoria’s most marginal seats the future workforce, working on issues of innovation quality NDIS? (Frankston, Carrum and Bentleigh). and training and building support against contracting out. HACSU is campaigning to save public disability services after the Andrews Labor • Staged a pre-Christmas statewide protest in Melbourne; an event that received widespread media • We are strongly advocating for detailed workforce Government’s announcement that it will privatise disability services. There’s been a wide attention. research that looks at the key issues of workforce range of campaign activities, and we’ve attracted the Government’s attention. retention and attraction, and the impact contracting • Set up a public petition; check it out via out would have on retention. However, to win this campaign, and maintain quality disability services for Victorians, dontdisposeofdisability.org, don’t forget to make sure your colleagues sign! • We have put forward an important disability service we have to sustain the grassroots union campaign. This means, every member has to quality policy, which is about the need for ongoing contribute. • HACSU is working hard to contact families, friends and recognition of disability work as a profession, like guardians of people with disabilities to further build nursing and teaching, and the introduction of new We need to be taking collective and individual actions. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, 5 JUNE 2019 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education ......................... The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Transport Infrastructure ............................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice and Minister for Victim Support .................... The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ............................................ The Hon. MP Foley, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Workplace Safety ................. The Hon. J Hennessy, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Ports and Freight -

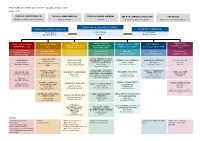

DPC-Org-Chart-April-2021.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF PREMIER AND CABINET— ORGANISATIONAL CHART 12 April 2021 THE HON. DANNY PEARSON THE HON. JAMES MERLINO THE HON. DANIEL ANDREWS THE HON. GABRIELLE WILLIAMS TIM PALLAS Minister for Government Services Deputy Premier Premier Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Industrial Relations DEPARTMENT OF PREMIER AND CABINET RECOVERY TRACKING & ANALYTICS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Marcus Walsh Jeremi Moule Jane Gardam Executive Director Secretary Executive Director CABINET, SOCIAL POLICY & INDUSTRIAL LEGAL, LEGISLATION & DIGITAL VICTORIA ECONOMIC POLICY & STATE FIRST PEOPLES— COMMUNICATIONS & INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS VICTORIA GOVERNANCE (LLG) (DV) PRODUCTIVITY (EPSP) STATE RELATIONS (FPSR) CORPORATE (CCC) RELATIONS (SPIR) (IRV) Toby Hemming Vivien Allimonos Vivien Allimonos Kate Houghton Tim Ada Elly Patira Matt O’Connor Deputy Secretary & A/ Chief Executive Officer Deputy Secretary Deputy Secretary Deputy Secretary A/ Deputy Secretary Deputy Secretary General Counsel CYBERSECURITY COVID COORDINATION & GOVERNANCE CABINET OFFICE PERFORMANCE / FAMILIES, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ABORIGINAL VICTORIA PRIVATE SECTOR John O’Driscoll Vicky Hudson FAIRNESS & HOUSING Sophie Colquitt Tim Kanoa Lissa Zass Chief Information Security Rachel Cowling Executive Director Lucy Toovey A/ Executive Director Executive Director Director Officer A/ Executive Director Executive Director DIGITAL DESIGN & EDUCATION / JUSTICE / TREATY / ABORIGINAL OFFICE OF THE COMMUNITY SECURITY & ECONOMIC STRATEGY PUBLIC SECTOR INNOVATION CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AFFAIRS POLICY -

War on Waste: Building a Circular Economy

War on waste: building a circular economy Keynote speaker: The Hon. Lily D’Ambrosio MP, Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change Wednesday 26 February 2020, 11.45am to 2.00pm Park Hyatt EVENT MAJOR SPONSOR www.ceda.com.au agenda 11.45am Registrations 12.15pm Welcome Fleur Morales State Director Vic/Tas, CEDA 12.20pm Introduction Kate Roffey Director Deals, Investment and Major Projects, Wyndham City 12.30pm Keynote address The Hon. Lily D’Ambrosio MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change 12.50pm Lunch 1.20pm Moderated discussion and questions During moderated discussion CEDA will take online questions. Go to ceda.pigeonhole.at/CIRCULARECONOMY and enter passcode CIRCULARECONOMY The Hon. Lily D’Ambrosio MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change Kate Roffey Director Deals, Investment and Major Projects, Wyndham City Claire Ferris Miles Chief Executive Officer, Sustainability Victoria Joan Ko - Moderator Advisory, Planning and Design – Victoria Lead, Arup 1.55pm Vote of thanks Joan Ko Advisory, Planning and Design – Victoria Lead, Arup 2.00pm Close . sponsor Event major sponsor City of Wyndham WYNnovation is an initiative proudly delivered by Wyndham City Council. Now in its third year, WYNnovation is designed to enable innovation and entrepreneurship among the City’s businesses and the broader community. The month of February has seen a number of key events and workshops with the sponsorship of today’s CEDA Luncheon concluding a suite of highly engaging and innovative programs. As one of the fastest growing municipalities in Australia, Council is working with our partners to ensure Wyndham is a place of opportunity that builds an attractive business and investment environment. -

Annual Report 2014-15

V C O S S A N N U A L R E P O R T 2 0 1 4 - 2 0 1 5 1 From the President 2 From the CEO 3 Advocate for social justice 5 Reports published and submissions made 6 Build a strong community sector 8 Strengthen our public presence 10 VCOSS blogs and media releases 12 Collaborate for greater impact 14 Sustain a healthy organisation 15 VCOSS Board 2014–15 16 Staff, Funders, Partners and Supporters 17 VCOSS Members 2014–15 18 Treasurer’s report 19 Financial statements For more information about VCOSS or to become a member, contact: Victorian Council of Social Service Level 8, 128 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3000 T: +61 3 9235 1000 Freecall: 1800 133 340 F: 03 9654 5749 W: www.vcoss.org.au E: [email protected] Twitter: @vcoss Authorised by: Emma King, Chief Executive Officer © Copyright 2015 Victorian Council of Social Service Printing: Officeworks Design: Louisa Roubin Enquiries: Kellee Nolan, Publications Editor E: [email protected] ISSN 1324 8588 ABN 23 005 014 988 1 From the President Both the present and the future have been firmly on the agenda at VCOSS this year. We have advocated strongly for social justice, while also casting our view forward to develop a strategy that strengthens the community’s voice against poverty and inequality into the future. On behalf of the board I would like to express our appreciation for the efforts of all VCOSS staff, under the outstanding leadership of our Chief Executive Officer Emma King, and our new Deputy Chief Executive Officer Mary Sayers, for their work in partnership with members and people with lived experience of poverty and disadvantage, to present wide-ranging policy, research and solutions, and create a powerful voice against poverty and inequality. -

Parliament of Victoria

Current Members - 23rd January 2019 Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Hon The Hon. Daniel Michael 517A Princes Highway, Noble Park, VIC, 3174 Premier Andrews MP (03) 9548 5644 Leader of the Labor Party Member for Mulgrave [email protected] Hon The Hon. James Anthony 1635 Burwood Hwy, Belgrave, VIC, 3160 Minister for Education Merlino MP (03) 9754 5401 Deputy Premier Member for Monbulk [email protected] Deputy Leader of the Labor Party Hon The Hon. Michael Anthony 313-315 Waverley Road, Malvern East, VIC, 3145 Shadow Treasurer O'Brien MP (03) 9576 1850 Shadow Minister for Small Business Member for Malvern [email protected] Leader of the Opposition Leader of the Liberal Party Hon The Hon. Peter Lindsay Walsh 496 High Street, Echuca, VIC, 3564 Shadow Minister for Agriculture MP (03) 5482 2039 Shadow Minister for Regional Victoria and Member for Murray Plains [email protected] Decentralisation Shadow Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Leader of The Nationals Deputy Leader of the Opposition Hon The Hon. Colin William Brooks PO Box 79, Bundoora, VIC Speaker of the Legislative Assembly MP Suite 1, 1320 Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC, 3083 Member for Bundoora (03) 9467 5657 [email protected] Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Mr Shaun Leo Leane MLC PO Box 4307, Knox City Centre, VIC President of the Legislative Council Member for Eastern Metropolitan Suite 3, Level 2, 420 Burwood Highway, Wantirna, VIC, 3152 (03) 9887 0255 [email protected] Ms Juliana Marie Addison MP Ground Floor, 17 Lydiard Street North, Ballarat Central, VIC, 3350 Member for Wendouree (03) 5331 1003 [email protected] Hon The Hon. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

EXTRACT FROM BOOK PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 24 July 2018 (Extract from book 10) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry (from 16 October 2017) Premier ........................................................ The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Emergency Services .................................................... The Hon. J. A. Merlino, MP Treasurer and Minister for Resources .............................. The Hon. T. H. Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Major Projects .......... The Hon. J. Allan, MP Minister for Industry and Employment ............................. The Hon. B. A. Carroll, MP Minister for Trade and Investment, Minister for Innovation and the Digital Economy, and Minister for Small Business ................ The Hon. P. Dalidakis, MLC Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Suburban Development ....................................... The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Roads and Road Safety, and Minister for Ports ............ The Hon. L. A. Donnellan, MP Minister for Tourism and Major Events, Minister for Sport and Minister for Veterans ................................................. The Hon. J. H. Eren, MP Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries .......... The Hon. M. P. Foley, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services ............. The Hon. J. Hennessy, MP Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Minister for Industrial Relations, Minister for Women and Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence ............................................. The Hon. N. M. Hutchins, MP Special Minister of State ........................................ -

2019 Economic and Political Overview in Hobart

2019 Economic and Political Overview in Hobart Keynote speaker: The Hon. Peter Gutwein, Treasurer of Tasmania Monday 25 February 2019, 11.45am to 2.00pm Hotel Grand Chancellor Hobart www.ceda.com.au agenda 11.45am Registrations 12.10pm Welcome and Introduction Michael Camilleri State Director Victoria & Tasmania, CEDA 12.15pm Opening address Michael Blythe Chief Economist and Managing Director, Economics, Commonwealth Bank of Australia 12.30pm Moderated discussion and Q&A Michael Blythe Chief Economist and Managing Director, Economics, Commonwealth Bank of Australia Moderated by Michael Camilleri State Director Victoria & Tasmania, CEDA 12.40pm Lunch 1.10pm Introduction Michael Camilleri State Director Victoria & Tasmania, CEDA 1.15pm Keynote address The Hon. Peter Gutwein Treasurer of Tasmania 1.30pm Moderatied discussion and Q&A The Hon. Peter Gutwein Treasurer of Tasmania Moderated by Michael Camilleri State Director Victoria & Tasmania, CEDA 2.00pm Close . keynote speaker The Hon. Peter Gutwein Treasurer of Tasmania Raised at Nunamara near Launceston and educated at Myrtle Park Primary School, Queechy High School and Deakin University, Peter Gutwein is a proud and passionate Tasmanian. Peter, his wife Amanda and children Millie and Finn live in the Tamar Valley. The family still maintain strong connections to Bridport and North East Tasmania. Peter’s background is in the Financial Planning Industry. He enjoyed a successful career in financial services working in senior management positions both in Australia and in Europe. He holds qualifications in Business Administration and Financial Planning and also spent two years as an Adviser to a senior Federal coalition cabinet Minister during the 1990s. Peter was first elected to the Tasmanian Parliament in 2002 and has continuously represented the electorate of Bass in Northern Tasmania since then. -

Letter to the Hon. Daniel Andrews, Premier of Victoria

4 May 2020 The Hon. Daniel Andrews, Premier of Victoria 1 Treasury Place Melbourne Victoria 3002 By email: [email protected] Dear Premier, We are writing to you on behalf of Victoria’s building and construction industry. Firstly, congratulations to you and your colleagues for keeping Victorians safe during this pandemic. There is something special about Victorians. Whether it’s drought, fires, economic hurdles or disease we respect great leadership and we take leadership seriously. In our own industry, we have witnessed major disruptions in many countries. Meanwhile, in Victoria, a united group of employer associations and unions presented to you our commitment to the safety and wellbeing of our workers. We also put our strongly held belief that, as best as we could manage, our industry should continue to operate. You put your faith in us and designated our sector as an essential service. Albeit under new rules. Economic modelling undertaken by ACIL-Allen projected that the cost of a complete shutdown of the building and construction industry would have been $25.4 billion with 166,000 jobs lost. As you know, many Victorians are reliant on our industry for employment and business success. The building and construction sector provides 45% of Victoria’s tax revenue and is the state’s largest full-time employer. We are proud that we have repaid your faith in us. To date, there has been no community transfer of the virus on building and construction sites in Victoria. Two early cases of individuals self-reporting were resolved in rapid time and to maximum level of due care. -

Political Chronicles

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 54, Number 2, 2008, pp. 289-341. Political Chronicles Commonwealth of Australia July to December 2007 JOHN WANNA The Australian National University and Griffith University The Stage, the Players and their Exits and Entrances […] All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; [William Shakespeare, As You Like It] In the months leading up to the 2007 general election, Prime Minister John Howard waited like Mr Micawber “in case anything turned up” that would restore the fortunes of the Coalition. The government’s attacks on the Opposition, and its new leader Kevin Rudd, had fallen flat, and a series of staged events designed to boost the government’s stocks had not translated into electoral support. So, as time went on and things did not improve, the Coalition government showed increasing signs of panic, desperation and abandonment. In July, John Howard had asked his party room “is it me” as he reflected on the low standing of the government (Australian, 17 July 2007). Labor held a commanding lead in opinion polls throughout most of 2007 — recording a primary support of between 47 and 51 per cent to the Coalition’s 39 to 42 per cent. The most remarkable feature of the polls was their consistency — regularly showing Labor holding a 15 percentage point lead on a two-party-preferred basis. Labor also seemed impervious to attack, and the government found it difficult to get traction on “its” core issues to narrow the gap. -

FINN in the HOUSE Speeches February to June 2019

FINN IN THE HOUSE Speeches February to June 2019 Published by Bernie Finn MP Member for Western Metropolitan Region Shadow Assistant Minister for Small Business Shadow Assistant Minister for Autism Opposition Whip in the Legislative Council Suite 101, 19 Lacy Street, Braybrook Vic 3019 Telephone (03) 9317 5900 • Fax (03) 9317 5911 Email [email protected] Web www.berniefinn.com Authorised and printed by Bernie Finn MP, Suite 101, 19 Lacy Street, Braybrook. This material was funded from the Parliament Electorate Office & Communications Budget. FINN IN THE HOUSE Speeches February to June 2019 CONTENTS Small Business ................................................................. 3 Economy and Infrastructure Committee .............17 Sunbury roundabout removal ................................... 3 Station Street, Sunbury level crossing Autism education ........................................................... 3 removal ............................................................................18 Energy supply .................................................................. 3 Governor’s Speech .......................................................18 Wyndham Vale gang violence ................................... 6 Brimbank police numbers .........................................19 Tullamarine Freeway widening ................................. 6 Sunbury Road duplication ........................................19 Climate change ............................................................... 6 Yarraville parking meters