Genderforking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transantiquity

TransAntiquity TransAntiquity explores transgender practices, in particular cross-dressing, and their literary and figurative representations in antiquity. It offers a ground-breaking study of cross-dressing, both the social practice and its conceptualization, and its interaction with normative prescriptions on gender and sexuality in the ancient Mediterranean world. Special attention is paid to the reactions of the societies of the time, the impact transgender practices had on individuals’ symbolic and social capital, as well as the reactions of institutionalized power and the juridical systems. The variety of subjects and approaches demonstrates just how complex and widespread “transgender dynamics” were in antiquity. Domitilla Campanile (PhD 1992) is Associate Professor of Roman History at the University of Pisa, Italy. Filippo Carlà-Uhink is Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, UK. After studying in Turin and Udine, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and as Assistant Professor for Cultural History of Antiquity at the University of Mainz, Germany. Margherita Facella is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Pisa, Italy. She was Visiting Associate Professor at Northwestern University, USA, and a Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Münster, Germany. Routledge monographs in classical studies Menander in Contexts Athens Transformed, 404–262 BC Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein From popular sovereignty to the dominion -

Cavar Thesis Final 2020.Pdf

Abstract: What, how, and who is transbutch? In this thesis, I examine memoirs and personal essays that define and defy boundaries between “butch" and “transmasculine" subjectivity –– and investigate my own queer experience in the process –– in order to counter the myth of an irreparable trans/ butch divide. Deemed by some to be “border wars,” conflicts between transness and butchness are emblematic of the contested (hi)stories on which the identities are founded: namely, white supremacy, colonialism, transmedicalism, and lesbian separatism/trans-exclusionary radical fem- inism. Ensuing identity-battles –– which have increased with increased access to biomedical transition –– rely on a teleological approach to identity, and, I argue, may only be ameliorated by prioritizing experiential multiplicity and political affinity over fixed, essential truth. Through en- gagement with a variety of personal narratives by authors such as S. Bear Bergman, Ivan Coyote, Rae Spoon, and blogger MainelyButch, I counter the understanding of identity as intrinsic and immutable, showing instead the dynamism of transbutch life, its stretchiness as a personal and community signifier, and its constant re-definition by its occupants. 2 Enacting Transbutch: Queer Narratives Beyond Essentialism BY: SARAH LYNN CAVAR Bachelor of Arts Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, MA 2020 3 Acknowledgements: How to start but with a story. I am about to send this final document to my advisor, Jacquelyne Luce, in anticipation of a thesis defense that is as I write this only days away. Without her sup- port and guidance at every stage –– all the way from a disorganized 120-page Google Doc of notes to the PDF you now read –– this thesis would not be possible. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Gender Identity: Pending? Identity Development and Health Care Experiences of Transmasculine/Genderqueer Identified Individuals Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2ph0m6vr Author Schulz, Sarah L. Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gender Identity: Pending? Identity Development and Health Care Experiences of Transmasculine/Genderqueer Identified Individuals By Sarah L. Schulz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Welfare in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Eileen Gambrill, Chair Professor Lorraine Midanik Professor Kristin Luker Fall 2012 1 Abstract Gender Identity: Pending? Identity development and Healthcare Experiences of Transmasculine/Genderqueer Identified Individuals by Sarah L. Schulz Doctor of Philosophy in Social Welfare University of California, Berkeley Professor Eileen Gambrill, Chair The purpose of this study was to explore the identity development process and health care experiences of individuals who identify their gender somewhere along the transmasculine spectrum. Historically, researchers and clinicians have viewed the transgender experience through a lens of medical pathologization and have neglected to acknowledge the diverse experiences of those who identify as transmasculine. The current standards of care for accessing transition-related health services require transmasculine individuals to express a narrative of distress in order to gain access to services, which further pathologizes those with complex identities that transcend the traditional categories of “male” and “female”. Using a qualitative grounded theory approach, data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 28 transmasculine identified individuals. -

Transgender Medicine for the Primary Care Provider October 19, 2017

Transgender Medicine for the Primary Care Provider October 19, 2017 Daniel Shumer, MD Assistant Professor in Pediatrics Division of Pediatric Endocrinology University of Michigan Disclosures I have no financial relationships to disclose Objecves • IntroducDon, three vigneFes • Define gender dysphoria • Review approaches to paents with gender dysphoria • Outline pharmacologic therapies used in transgender medicine • Outline challenges and barriers to care, and future direcDons for the field. Case 1 • Timmy is presents to the pediatrician at age 8 years… – Since age 4 he has very much wished he were a girl, oQen stang emphacally, “I’m not a boy, I’m a girl!” – He has been secretly playing dress-up in his older sister’s clothes – He loves to play with dolls and pretends that he is a mother feeding and changing their diapers – At school he likes to play with girls, and avoids rough-and- tumble acDviDes with boys – Throws tantrums when redirected away from feminine behaviors – Recently stated that “I just want to chop it off!” in reference to his penis – Parents are distressed and don’t know how to proceed Case 1 Case 2 • Sarah “ScoF” is a 14 year-old natal girl who presents year-old girl presents to endocrine clinic with his parents, referred by pediatrician – Described by parents as a “tomboy” when younger – Over Dme, has more clearly expressed a male idenDty – Social transiDon at age 12 – More socially withdrawn and depressed with new cung behavior – Extremely distraught about new breast development – Very concerned about the prospect of menstruang -

Crossdresser and Transsexual TABLE of CONTENTS

INFORMATION FOR THI; FEMALE-TO-MALE crossdresser and transsexual TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ......................................1 The Difference Between Sexual Identity and Gender-Role Preference ................. 5 Crossdressi ng . ..................... 5 What is Transsexuality? ........................... 11 How Does a Transsexual Feel? ..................... 13 How Did It Happen? .............................. 15 Possible Biological Causes ......................... 17 Possible Psychological Causes ..................... 19 Psychological Treatment .......................... 20 How to Look 30 When You Are 30 ................... 22 Ong I I O O 0 e o O O o 22 C'oth' ..rl e I e e e O O e O e o O O O O I e I o I O 0 O I O e O o O O Oo 23 Face , Ha' I e I I O O I e e I O I O I e e O e O I O e 24 Body Language . · · · · Clothing and Shoe Sizes ................ · · · · · 25 Breast Binding, The Crotch ....... · · · · · · · · · · -~ The Men's Room ................. · · · · · · · · · · ~ Sex Reassignment .... · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 29 Hormone Therapy .. · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 31 S urgery . O O .0 I 0 0 O O O O O o O O O O 34 Homofogues in Female & Male Uro~en1tal Anatomy· · · 36 Accepting the New Man in the Family · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 38 Your Sex Life - Thoughts to Consider·· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 41 Contacts/ Referrals ..... · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 43 Readings.I .......... · · · · · · · · ....................· · · · · · · · · · · · · -

The Standards of Care for Gender Identity Disorders:1

HARRY BENJAMIN INTERNATIONAL GENDER DYSPHORIA ASSOCIATION'S THE STANDARDS OF CARE FOR GENDER IDENTITY DISORDERS:1 Committee Members: Stephen B. Levine MD (Chairperson), George Brown MD, Eli Coleman PhD., Peggy Cohen-Kettenis PhD, J. Joris Hage MD, Judy Van Maasdam MA, Maxine Petersen MA, Friedemann Pfafflin, MD, Leah C. Schaefer EdD. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Consultants: Dallas Denny MA, Domineco DiCeglie MD, Wolf Eicher MD, Jamison Green, Richard Green MD, Louis Gooren MD, Donald Laub MD, Anne Lawrence MD, Walter Meyer III MD, C. Christine Wheeler PhD ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE–Introductory Concepts page 2-3 PART TWO–Brief Reference Guide to the Standards of Care pages 3-10 PART THREE--The Full Text of the Standards of Care pages 10-29 Epidemiological Considerations--------------------------------------------- pages 10 Diagnostic Nomenclatures---------------------------------------------------- pages 10-14 The Mental Health Professional--------------------------------------------- pages 14-16 The Treatment of Children--------------------------------------------------- page 16-17 The Treatment of Adolescents----------------------------------------------- pages 17-18 Psychotherapy with Adults--------------------------------------------------- pages 18-21 The Real Life Experience----------------------------------------------------- page 21-22 Requirements -

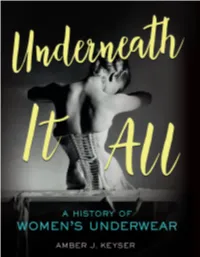

Amber J. Keyser

Did you know that the world’s first bra dates to the fifteenth century? Or that wearing a nineteenth-century cage crinoline was like having a giant birdcage strapped around your waist? Did you know that women during WWI donated the steel stays from their corsets to build battleships? For most of human history, the garments women wore under their clothes were hidden. The earliest underwear provided warmth and protection. But eventually, women’s undergarments became complex structures designed to shape their bodies to fit the fashion ideals of the time. When wide hips were in style, they wore wicker panniers under their skirts. When narrow waists were popular, women laced into corsets that cinched their ribs and took their breath away. In the modern era, undergarments are out in the open. From the designer corsets Madonna wore on stage to Beyoncé’s pregnancy announcement on Instagram, lingerie is part of everyday wear, high fashion, fine art, and innovative technological advances. This feminist exploration of women’s underwear— with a nod to codpieces, tighty- whities, and boxer shorts along the way—reveals the intimate role lingerie plays in defining women’s bodies, sexuality, gender identity, and body image. It is a story of control and restraint but also female empowerment and self- expression. You will never look at underwear the same way again. REINFORCED BINDING AMBER J. KEYSER TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS / MINNEAPOLIS For Lacy, who puts the voom in va-va-voom Cover photograph: Photographer Horst P. Horst took this image of a Mainbocher corset in 1939. It is one of the most iconic photos of fashion photography. -

Care of the Patient Undergoing Sex Reassignment Surgery (SRS)

Care of the Patient Undergoing Sex Reassignment Surgery (SRS) Cameron Bowman, M.D., F.R.C.S.C.* Joshua Goldberg§ January 2006 a collaboration between Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society and Vancouver Coastal Health’s Transgender Health Program, with funding from the Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition’s Rainbow Health – Improving Access to Care initiative * Clinical Instructor, Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada; SRS Fellow, University Hospital of Gent, Belgium § Education Consultant, Transgender Health Program, Vancouver, BC, Canada Page i Acknowledgements Project coordinators Joshua Goldberg, Donna Lindenberg, and Rodney Hunt Research assistants Olivia Ashbee and A.J. Simpson Illustrations adapted by Donna Lindenberg Reviewers Trevor A. Corneil, MD, MHSc, CCFP Medical Director – Urban Primary Care, Vancouver Coastal Health; Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia; Vancouver, BC, Canada Stan Monstrey, MD, PhD Department of Plastic Surgery and Urology, University Hospital, University of Gent Gent, Belgium Kathy Wrath, RN Quesnel Public Health Northern Health Authority Quesnel, BC, Canada © 2006 Vancouver Coastal Health, Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society, and the Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition This publication may not be commercially reproduced, but copying for educational purposes with credit is encouraged. This manual is part of a set of clinical guidelines produced by the Trans Care Project, a joint initiative of Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society and Vancouver Coastal Health’s Transgender Health Program. We thank the Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition and Vancouver Coastal Health for funding this project. Copies of this manual are available for download from the Transgender Health Program website: http://www.vch.ca/transhealth. -

Identity Development and Health Care Experiences of Transmasculine/Genderqueer Identified Individuals

Gender Identity: Pending? Identity Development and Health Care Experiences of Transmasculine/Genderqueer Identified Individuals By Sarah L. Schulz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Welfare in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Eileen Gambrill, Chair Professor Lorraine Midanik Professor Kristin Luker Fall 2012 1 Abstract Gender Identity: Pending? Identity development and Healthcare Experiences of Transmasculine/Genderqueer Identified Individuals by Sarah L. Schulz Doctor of Philosophy in Social Welfare University of California, Berkeley Professor Eileen Gambrill, Chair The purpose of this study was to explore the identity development process and health care experiences of individuals who identify their gender somewhere along the transmasculine spectrum. Historically, researchers and clinicians have viewed the transgender experience through a lens of medical pathologization and have neglected to acknowledge the diverse experiences of those who identify as transmasculine. The current standards of care for accessing transition-related health services require transmasculine individuals to express a narrative of distress in order to gain access to services, which further pathologizes those with complex identities that transcend the traditional categories of “male” and “female”. Using a qualitative grounded theory approach, data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 28 transmasculine -

Aligned with the CAPS Life Orientation Curriculum

Sexuality & Gender Pack Aligned with the CAPS Life Orientation Curriculum Compiled by: Tazme Pillay (South African History Online) & Elliot Naude Genevieve Louw and Linda Chernis (GALA- Queer Archive) Table of Contents BASICS OF SEXUALITY & GENDER Introduction 1 Glossary 1 What does "LGBTQIA+" stand for? 3 BIOLOGICAL SEX VS. GENDER Understanding the difference 14 What is a pronoun? 15 Misgendering 16 Speaking in a non-binary way 17 Menstruation 17 QUESTIONING YOUR SEXUALITY & GENDER IDENTITY Gender Dysphoria 19 Support for questioning people 20 Coming out 21 The Closet 21 SEXUAL HEALTH FOR LGBTQIA+ STUDENTS Basics of sexual health 22 Sex between people with penises 23 Sex between people with vaginas 23 DISCRIMINATION & VIOLENCE AGAINST THE LGBTQIA+ COMMUNITY Discrimination & violence 24 Myths & facts about LGBTQIA+ people 25 Myths & facts about sexual orientation 25 Myths & facts about trans people 26 The affects of discrimination on the LGBTQIA+ 27 Violence against LGBTQIA+ people 28 LGBTQIA+ ORGANISATIONS Resources for LGBTQIA+ youth 32 Introduction & Glossary This guide will break down the “LGBTQIA+” acronym, and provide information on each of the sexual orientations and gender identities represented by each letter of the acronym. This guide will also explore the topic of gender identity and what it means to be trans, how gender is different to biological sex, and will provide sexual and mental health information for LGBTQIA+ students by covering important topics such as Coming Out. When it comes to sexuality and gender, there is often a lot of terminology to learn and understand. It is important to get to know what these different terms mean, and how they apply to a person’s identity. -

Gender Affirming Care for the Rehabilitation Professional

4/6/2021 Jennifer Stone, PT, DPT, OCS, PHC BEST PRACTICES FOR REHAB Program Director, Evidence In Motion Pelvic Health Physical Therapist, Rehabilitative Services, Mizzou Therapy Services, PROFESSIONALS FOR Columbia, MO Pronouns: She/her Special thanks to Mason Aid, pronouns GENDER AFFIRMING CARE they/them 1 1 After this course, participants will be able to: Provide definitions for at least 3 commonly used terms when defining genders and individuals who identify in different ways across the gender spectrum Name at least 2 reasons why correct use of pronouns is important and explain how to LEARNING incorporate this into medical documentation Discuss the impact of hormone therapy on OUTCOMES the musculoskeletal system and explain how to assist patients who experience musculoskeletal pain during or after hormone therapy Describe the types of gender affirming surgery along with a basic description of rehabilitative considerations post surgically 2 2 1 4/6/2021 Gender Sex Sex assigned at birth Transgender man DEFINITIONS Transgender woman Nonbinary Cisgender Gender dysphoria 3 3 Gender divergent Gender affirming care Transition Social Medical Surgical DEFINITIONS Microaggression Heteronormative Cisnormative Sexuality/sexual orientation 4 4 2 4/6/2021 5 5 Exact prevalence is not known, due to lack of accurate large scale studies Varies per country Estimated 0.7% of American young people identify as gender divergent in some way Nearly 1 million adults in the US are transgender Survey found 12% of millennials identify as gender IMPORTANCE -

An Introduction to Roman Women's Clothing

AN INTRODUCTION TO ROMAN WOMEN ’S CLOTHING By Domina Arria Marina ([email protected] ) Website: http://www.arriamarina.com Thank you for your interest in Ancient Roman women’s clothing. Please understand that this is a working document, and will be edited as my research dictates. All errors are mine. Feel free to ask me any questions that you have!! I look forward to your emails asking for updates, or if you have information to share or see errors in my document. OVERVIEW OF THE TIME PERIOD The Roman Empire was one of the greatest civilizations in history, beginning in 753 BC. Rome controlled over two million square miles from the Rhine River to Egypt and from Britain to Asia Minor. Because the timeline stretches over a thousand years, the styles of clothing vary significantly from the beginning of the Roman Monarchy (753-509 BCE), through the Republic (509-27 BCE), and the Imperial Period until the end of the Empire (27 BCE to 476 AD). My focus is the Late Republic to early Imperial (50 BCE to 79 AD) coinciding with the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the decimation, and subsequent preservation, of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Oplontis. The goal of this paper is to be helpful for SCAdians who want to dress Roman with a modicum of accuracy. If you are Byzantine, Romano-Celt**, etc., this will be a helpful start but you will need to continue your research. (**My own persona is Romano-Celt, so I have included a page at the end of this document to provide some insight into that garb!) PAGE 1 INTERPRETING ARTWORK In the absence of any surviving clothing, art and literature provide the only evidence of classical dress.