Studentthesis-Andrew Bishop 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Chapter Will Demonstrate How Anglo-Catholicism Sought to Deploy

Building community: Anglo-Catholicism and social action Jeremy Morris Some years ago the Guardian reporter Stuart Jeffries spent a day with a Salvation Army couple on the Meadows estate in Nottingham. When he asked them why they had gone there, he got what to him was obviously a baffling reply: “It's called incarnational living. It's from John chapter 1. You know that bit about 'Jesus came among us.' It's all about living in the community rather than descending on it to preach.”1 It is telling that the phrase ‘incarnational living’ had to be explained, but there is all the same something a little disconcerting in hearing from the mouth of a Salvation Army officer an argument that you would normally expect to hear from the Catholic wing of Anglicanism. William Booth would surely have been a little disconcerted by that rider ‘rather than descending on it to preach’, because the early history and missiology of the Salvation Army, in its marching into working class areas and its street preaching, was precisely about cultural invasion, expressed in language of challenge, purification, conversion, and ‘saving souls’, and not characteristically in the language of incarnationalism. Yet it goes to show that the Army has not been immune to the broader history of Christian theology in this country, and that it too has been influenced by that current of ideas which first emerged clearly in the middle of the nineteenth century, and which has come to be called the Anglican tradition of social witness. My aim in this essay is to say something of the origins of this movement, and of its continuing relevance today, by offering a historical re-description of its origins, 1 attending particularly to some of its earliest and most influential advocates, including the theologians F.D. -

Chapter 4: BISHOP ROBERT GRAY – an ASSESSMENT

A clash of churchmanship? Robert Gray and the Evangelical Anglicans 1847 – 1872 Alan Peter Beckman Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Church and Dogma History) at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. Supervisor: Dr J Newby Co-supervisor: Dr P H Fick May 2011. 2 ABSTRACT This study investigates the initial causes of Anglican division in South Africa in order to assess whether the three Evangelical parishes in the Cape Peninsula were justified in declining to join the Church of the Province of South Africa when it was formally constituted as a voluntary association in January 1870. The research covered the following: Background to the period in England and at the Cape, based on the histories pertinent to the period; An assessment of the differences in churchmanship between the Evangelicals and the Anglo-Catholics, through study of the applicable literature; A critical assessment of the character, churchmanship, aims, and actions of the first bishop of Cape Town, Robert Gray, drawn from the two-volume biography of his life, his journals and documents obtained in the archives; An analysis of the disputes between Bishop Gray and two Evangelical clergymen, analyzed from the published correspondence and archive material. The conclusion of the study is that the differences in churchmanship between the Evangelicals and the Anglo Catholics were very substantial and when coupled with the character, aims and actions of Bishop Gray, left the Evangelicals with little option but to decline the invitation to join his voluntary association. KEY WORDS Anglican Evangelical Anglo-Catholic Tractarian Churchmanship 3 UITREKSEL In hierdie studie word die aanvanklike oorsake van Anglikaanse verdeeldheid in Suid-Afrika ondersoek ten einde te bepaal of die drie Evangeliese gemeentes in die Kaapse Skiereiland geregverdig was om nie aan te sluit by die Church of the Province of South Africa nie toe dit formeel gekonstitueer was as 'n vrywillige vereniging in Januarie 1870. -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an Historical and Theological Examination of the Role of Ecclesiology in the Church of England Since the Second World War

Durham E-Theses Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the church of England since the second world war Bagshaw, Paul How to cite: Bagshaw, Paul (2000) Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the church of England since the second world war, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4258/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the Church of England since the Second World War The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should i)C published in any form, including; Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. -

Another Anglican View 11 C

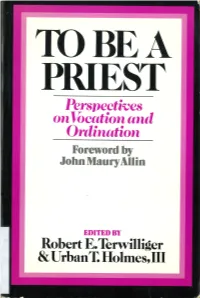

TO BE A PRIEST Perspectives on Vocation and Ordination edited by RaBERT E. TERWILLIGER URBAN T. HOLMES, ItrI with a Foreword by John Maury Allin A Crossroad Book THE SEABURY PRESS O NEW YORK The Seabury Press 815 Second Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 Copyright O 1975 by The Seabury Press, Inc. Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical reviews and articles. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CÄTALOGING IN PUBLIC.A,TION DAT.A Main entry under title: To be a priest. "A Crossroad book." Bibliography: p. 1. Priests-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Priesthood-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Ter- wilÌiger, Robert E. II. Holmes, Urban Tigner, 1930- 8V662.T6 262'.r4 75-28248 ISBN 0-8164-2592-2 contents FOREWORD John Maurg AIIín rx c. PREFACE Robert E. Teruillíger and Urban T' Holmes be reproduced in any manner whatsoever ter, except for brief quotations in cri;ic; Pørt L What ís a Príest? 1. One Anglican View Robert E. TerwíIlíger 2. Another Anglican View 11 C. FitøSímons AIIíson 3. An Orthodox Statement 2L Thomas HoPko 4. A Roman Catholic Catechism 29 Quentín Quesnell Pørt IL The Príesthood ín the Bíble ønd Hístory 5. Priesthood in the History of Religions 45 loseph Kítagaua 6. The Priesthood of Christ 55 MEIes M' Bourke 7. Priesthood in the New Testament 63 ,UBLICATION DATA Louís Weil 8. Presbyters in the EarlY Church 7L MasseE H. ShePherd, Jr' 9. -

The Beginnings of Anglican Theological Education in South Africa, 1848–1963

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 63, No. 3, July 2012. f Cambridge University Press 2012 516 doi:10.1017/S0022046910002988 The Beginnings of Anglican Theological Education in South Africa, 1848–1963 by PHILIPPE DENIS University of KwaZulu-Natal E-mail: [email protected] Various attempts at establishing Anglican theological education were made after the arrival in 1848 of Robert Gray, the first bishop of Cape Town, but it was not until 1876 that the first theological school opened in Bloemfontein. As late as 1883 half of the Anglican priests in South Africa had never attended a theological college. The system of theological education which developed afterwards became increasingly segregated. It also became more centralised, in a different manner for each race. A central theological college for white ordinands was established in Grahamstown in 1898 while seven diocesan theological colleges were opened for blacks during the same period. These were reduced to two in the 1930s, St Peter’s College in Johannesburg and St Bede’s in Umtata. The former became one of the constituent colleges of the Federal Theological Seminary in Alice, Eastern Cape, in 1963. n 1963 the Federal Theological Seminary of Southern Africa, an ecumenical seminary jointly established by the Anglican, Methodist, I Presbyterian and Congregational churches, opened in Alice, Eastern Cape. A thorn in the flesh of the apartheid regime, Fedsem, as the seminary was commonly called, trained theological students of all races, even whites at a later stage of its history, in an atmosphere -

The Anglo-Catholic Tradition in Australian Anglicanism Dr David

The Anglo-Catholic Tradition in Australian Anglicanism Dr David Hilliard Reader in History, Flinders University Adelaide, Australia Anglicanism in Australia has had many Anglo-Catholics but no single version of Anglo-Catholicism.1 Anglo-Catholics have comprised neither a church nor a sect, nor have they been a tightly organised party. Within a framework of common ideas about the apostolic succession, the sacraments and the central role of ‘the Church’ in mediating salvation, they were, and remain, diverse in outlook, with few organs or institutions to link them together and to promote common goals. Since the mid-nineteenth century, in Australia as in England, two very different trends in the movement can be identified. There were Anglo- Catholics who were primarily concerned with personal religion and the relationship of the individual soul to God, and those, influenced by Incarnational theology, who were concerned to draw out the implications of the Catholic 1 Published works on Anglo-Catholicism in Australia include: Brian Porter (ed.), Colonial Tractarians: The Oxford Movement in Australia (Melbourne, 1989); Austin Cooper, ‘Newman—The Oxford Movement—Australia’, in B.J. Lawrence Cross (ed.), Shadows and Images: The Papers of the Newman Centenary Symposium, Sydney, August 1979 (Melbourne, 1981), pp. 99-113; Colin Holden, ‘Awful Happenings on the Hill’: E.S. Hughes and Melbourne Anglo-Catholicism before the War (Melbourne, 1992) and From Tories at Prayer to Socialists at Mass: St Peter’s, Eastern Hill, Melbourne, 1846-1990 (Melbourne, 1996); Colin Holden (ed.), Anglo-Catholicism in Melbourne: Papers to Mark the 150th Anniversary of St Peter’s, Eastern Hill, 1846-1996 (Melbourne, 1997); L.C Rodd, John Hope of Christ Church St Laurence: A Sydney Church Era (Sydney 1972); Ruth Teale, ‘The “Red Book” Case’, Journal of Religious History, vol. -

The Spirituality of Andrew Murray Jr. (1828-1917). a Theological-Critical Assessment

THE SPIRITUALITY OF ANDREW MURRAY JR. (1828-1917). A THEOLOGICAL-CRITICAL ASSESSMENT HEE-YOUNG LEE THESIS PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (THEOLOGY) PROMOTER: PROF. DR. R.M. BRITZ DEPARTMENT OF ECCLESIOLOGY FACULTY OF THEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF THE FREE STATE NOVEMBER 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Hallelujah! Now this study is complete. A lot of time and effort was put into the work before it could be finished. Prayer, kindness, intellectual supervision and all kinds of support from my family, teachers, pastors, and colleagues are an integral part of this thesis. Without any one of them, this thesis could not have been produced. To begin with I want to give many thanks to God who led me to do this work and to finish it on time. Although there were various difficulties during the study, I was able to overcome those difficulties and to proceed with my studies by the grace of God. I confess that this work is nothing but a result of His lavish grace upon an unworthy sinner. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor, Professor Dr. Rudolph M. Britz who has sincerely and patiently promoted me up to now. His kind, intellectual and detailed supervision, which can be summarised as many hours of patient guidance, editorial scrutiny, and caring encouragement from beginning to end, went beyond what was simply required and provided the best form of guidance in my efforts. His precious advice; “Do not study ideologically. Let primary sources tell and let them guide your study!” was to be a valuable motto, especially considering my goal of being a church- historian. -

Anglican Women Missionaries and Ecclesiastical Politics in 20Th-Century South Africa

“A spirit of comradeship in work”? Anglican women missionaries and ecclesiastical politics in 20th-century South Africa Deborah Gaitskell School of Oriental and African Studies, London University, London, United Kingdom Abstract In the first half of the twentieth century, between one and two hundred British women at any one time were serving among South Africa’s black population as paid Anglican missionaries. From 1913, they joined together in a Society of Women Missionaries, holding regular conferences until 1955 and producing an informative journal. These missionaries, often lifelong church employees and occasionally deaconesses, were the first women whom the church hierarchy accommodated as actual lay representatives in its previously all-male preserves of mission consultation and governance, 50 years before women could be elected to Provincial Synod. The SWM Journal’s coverage of its dealings with the Provincial Missionary Conference and Board of Missions encompasses struggles over female inclusion, the inspiration derived from involvement, and key issues raised – especially evangelistic training for women and the hope of comradeship with men in shared missionary work. This period of white female mission leader- ship and modest official recognition merits greater acknow- ledgement in the history of both Anglican church government in South Africa and the development of female ministry, inclu- ding ordination to the priesthood. Introduction: Mission, church representation and women’s ministry Miss J Batcham, a British woman missionary at work in South Africa at the end of the 1930s, voiced great hopes for projected parallel male and female Anglican cultural investigations into African adolescent rites of passage: One of the immediate results of the discussion on Father Amor’s paper is a Resolution asking the S.W.M to form a Committee, and present a report to the next P.M.C. -

Reproduced by Permission on Project Canterbury, 2006 HIGH CHURCH VARIETIES Continuity and Discontinui

HIGH CHURCH VARIETIES Continuity and Discontinuity in Anglican Catholic Thought MATTIJS PLOEGER Westcott House, Cambridge, 1998 Originally published as: Mattijs Ploeger, High Church Varieties: Three Essays on Continuity and Discontinuity in Nineteenth-Century Anglican Catholic Thought (Publicatiereeks Stichting Oud-Katholiek Seminarie, volume 36), Amersfoort NL: Stichting Oud-Katholiek Boekhuis, Sliedrecht NL: Merweboek, 2001. For other volumes of the Publication Series of the Old Catholic Seminary, see www.okkn.nl/?b=494. For this 2006 internet edition the author has integrated the original three essays into one text consisting of three chapters. The Revd Mattijs Ploeger, M.A, studied at the Theological Faculty of Leiden University and the Old Catholic Seminary at Utrecht University (the Netherlands). Additionally he spent five months at the Anglican theological college Westcott House, Cambridge (United Kingdom), where the present text was written. In 1999 he was ordained to the diaconate and the presbyterate in the Old Catholic diocese of Haarlem (the Netherlands), where he serves as a parish priest. Fr Matt is a member of several ecumenical liturgical organisations in the Netherlands and is preparing a dissertation on liturgical/eucharistic ecclesiology at Utrecht University. He has published articles in the Dutch liturgical journal Eredienstvaardig and in the Old Catholic theological quarterly Internationale Kirchliche Zeitschrift. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his gratitude to the Archbishop of Utrecht, the Most Revd Dr Antonius Jan Glazemaker, and the Bishop of Haarlem, the Rt Revd Dr Jan-Lambert Wirix- Speetjens, who allowed him to study at the Anglican theological college of Westcott House, Cambridge, during Easter Term and the summer of 1998. -

Exculpation of Colenso Both from a Theological Point of View but Also Because of the Situation in the Anglican Communion at This Particular Moment

Some comments on the possible “exculpation” of Bishop Colenso from Various sources. By D Pratt Bishop John William Colenso (1814-1883) was the first Anglican Bishop of Natal. A graduate of St. John's College, Cambridge and a Broad Churchman, he was appointed to the newly created diocese of Natal in 1853, as both bishop to the colonists and missionary bishop to the Zulu. Applying his Broad Church principles to the missionary context, he increasingly questioned conventional and theologically conservative missionary teaching and preaching, culminating in the publication, in 1861, of his study of St. Paul's Epistle to the Romans: newly translated and explained from a missionary point of view, in which he rejected the doctrines of both substitutionary atonement and everlasting punishment. The following year he also published the first part of his study of The Pentateuch and Book of Joshua Critically Examined, in which he challenged the historicity of the biblical narrative and applied historical critical methods to the text of the Pentateuch. Accused of heresy by his fellow bishops in Southern Africa, excommunicated by the Bishop of Cape Town, and also rejected by the overwhelming majority of the bishops of the Church of England, Colenso nevertheless established his legal right to remain Bishop of Natal. He continued as Bishop of Natal - despite the presence of a second and rival Bishop - until his death in 1883. His study of The Pentateuch and Book of Joshua Critically Examined eventually ran to seven large volumes, the last of which was published in 1879. In his later years he also took up the cause of the Zulu, arguing that they had been betrayed and mistreated by the British and colonial authorities. -

Salvation in Christ.Qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 53

Salvation in Christ.qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 53 Anglican Soteriology: Incarnation, Worship, and the Property of Mercy Douglas J. Davies Douglas J. Davies is a professor of religion in the Department of Theology, University of Durham, England. he birth of Anglicanism can be told with many tongues and motives. Kingly lust, political independence, the love of pure doctrine, martyred saints and scholars, and the free- Tdom of a new vernacular liturgy all play their part in the emergence of Anglicanism as a Protestant form of Catholic Chris- tianity. Anglicanism is marked less by doctrinal innovation, over sal- vation at least, than by its choice and complementarity of doctrine and practice. The task of writing on salvation in Anglicanism is not easy. For example, we might agree with Stephen Neill’s classic study whose fif- teenth and final chapter observed that no “special section” was devoted to Anglican theology precisely because “there is no particular Anglican theology.” He rehearses the importance of the Catholic Faith, of the Holy Scriptures, of the Creeds and first four General Councils of the undivided Church as furnishing everything that is “necessary to 53 Salvation in Christ.qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 54 Salvation in Christ salvation.”1 He also highlights a certain “Anglican attitude and an Angli- can atmosphere” that “defies analysis” and must be “felt and experienced in order to be understood.”2 While he further lists episcopacy, learning, continuity with the past, and tolerance as additional Anglican features, Neill emphasizes