One Inning Is Not a Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ........................... -

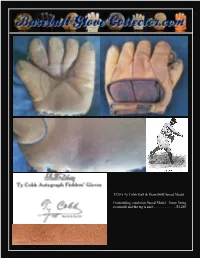

1920'S Ty Cobb Stall & Dean 8045 Speed

= 1920’s Ty Cobb Stall & Dean 8045 Speed Model Outstanding condition Speed Model. Inner lining is smooth and the tag is nice……...………...$5,250 1924-28 Babe Pinelli Ken Wel 550 Glove One of the more desirable Ken Wel NEVERIP models, this example features extremely supple leather inside and out. It’s all original. Can’t find any flaws in this one. The stampings are super decent and visible. This glove is in fantastic condition and feels great on the hand…….…………………………………………………………………..……….$500 1960’s Stall & Dean 7612 Basemitt = Just perfect. Gem mint. Never used and still retains its original shape………………………………………………...$95 1929-37 Eddie Farrell Spalding EF Glove Check out the unique web and finger attachments. This high-end glove is soft and supple with some wear (not holes) to the lining. Satisfaction guaranteed….………………………………………………………………………………..$550 1929 Walter Lutzke D&M G74 Glove Draper Maynard G74 Walter Lutzke model. Overall condition is good. Soft leather and good stamping. Does have some separations and some inside liner issues……………………………………………………………………..…$350 = 1926 Christy Mathewson Goldsmith M Glove Outstanding condition Model M originally from the Barry Halper Collection. Considered by many to be the nicest Matty example in the hobby....……………...$5,250 = 1960 Eddie Mathews Rawlings EM Heart of the Hide Glove Extremely rare Eddie Mathews Heart of the Hide model. You don’t see this one very often…………………………..$95 1925 Thomas E. Wilson 650 Glove This is rarity - top of the line model from the 1925 Thomas E. Wilson catalog. This large “Bull Dog Treated Horsehide” model glove shows wear and use with cracking to the leather in many areas. -

Awards Victory Dinner

West Virginia Sports Writers Association Victory Officers Executive committee Member publications Wheeling Intelligencer Beckley Register-Herald Awards Bluefield Daily Telegraph Spirit of Jefferson (Charles Town) Pendleton Times (Franklin) Mineral Daily News (Keyser) Logan Banner Dinner Coal Valley News (Madison) Parsons Advocate 74th 4 p.m., Sunday, May 23, 2021 Embassy Suites, Charleston Independent Herald (Pineville) Hampshire Review (Romney) Buckhannon Record-Delta Charleston Gazette-Mail Exponent Telegram (Clarksburg) Michael Minnich Tyler Jackson Rick Kozlowski Grant Traylor Connect Bridgeport West Virginia Sports Hall of Fame President 1st Vice-President Doddridge Independent (West Union) The Inter-Mountain (Elkins) Fairmont Times West Virginian Grafton Mountain Statesman Class of 2020 Huntington Herald-Dispatch Jackson Herald (Ripley) Martinsburg Journal MetroNews Moorefield Examiner Morgantown Dominion Post Parkersburg News and Sentinel Point Pleasant Register Tyler Star News (Sistersville) Spencer Times Record Wally’s and Wimpy’s Weirton Daily Times Jim Workman Doug Huff Gary Fauber Joe Albright Wetzel Chronicle (New Martinsville) 2nd Vice-President Secretary-Treasurer Williamson Daily News West Virginia Sports Hall of Fame Digital plaques with biographies of inductees can be found at WVSWA.org 2020 — Mike Barber, Monte Cater 1979 — Michael Barrett, Herbert Hugh Bosely, Charles L. 2019 — Randy Moss, Chris Smith Chuck” Howley, Robert Jeter, Howard “Toddy” Loudin, Arthur 2018 — Calvin “Cal” Bailey, Roy Michael Newell Smith, Rod -

Estimated Age Effects in Baseball

ESTIMATED AGE EFFECTS IN BASEBALL By Ray C. Fair October 2005 Revised March 2007 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 1536 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.econ.yale.edu/ Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair¤ Revised March 2007 Abstract Age effects in baseball are estimated in this paper using a nonlinear xed- effects regression. The sample consists of all players who have played 10 or more full-time years in the major leagues between 1921 and 2004. Quadratic improvement is assumed up to a peak-performance age, which is estimated, and then quadratic decline after that, where the two quadratics need not be the same. Each player has his own constant term. The results show that aging effects are larger for pitchers than for batters and larger for baseball than for track and eld, running, and swimming events and for chess. There is some evidence that decline rates in baseball have decreased slightly in the more recent period, but they are still generally larger than those for the other events. There are 18 batters out of the sample of 441 whose performances in the second half of their careers noticeably exceed what the model predicts they should have been. All but 3 of these players played from 1990 on. The estimates from the xed-effects regressions can also be used to rank players. This ranking differs from the ranking using lifetime averages because it adjusts for the different ages at which players played. It is in effect an age-adjusted ranking. -

Baseball All-Time Stars Rosters

BASEBALL ALL-TIME STARS ROSTERS (Boston-Milwaukee) ATLANTA Year Avg. HR CHICAGO Year Avg. HR CINCINNATI Year Avg. HR Hank Aaron 1959 .355 39 Ernie Banks 1958 .313 47 Ed Bailey 1956 .300 28 Joe Adcock 1956 .291 38 Phil Cavarretta 1945 .355 6 Johnny Bench 1970 .293 45 Felipe Alou 1966 .327 31 Kiki Cuyler 1930 .355 13 Dave Concepcion 1978 .301 6 Dave Bancroft 1925 .319 2 Jody Davis 1983 .271 24 Eric Davis 1987 .293 37 Wally Berger 1930 .310 38 Frank Demaree 1936 .350 16 Adam Dunn 2004 .266 46 Jeff Blauser 1997 .308 17 Shawon Dunston 1995 .296 14 George Foster 1977 .320 52 Rico Carty 1970 .366 25 Johnny Evers 1912 .341 1 Ken Griffey, Sr. 1976 .336 6 Hugh Duffy 1894 .440 18 Mark Grace 1995 .326 16 Ted Kluszewski 1954 .326 49 Darrell Evans 1973 .281 41 Gabby Hartnett 1930 .339 37 Barry Larkin 1996 .298 33 Rafael Furcal 2003 .292 15 Billy Herman 1936 .334 5 Ernie Lombardi 1938 .342 19 Ralph Garr 1974 .353 11 Johnny Kling 1903 .297 3 Lee May 1969 .278 38 Andruw Jones 2005 .263 51 Derrek Lee 2005 .335 46 Frank McCormick 1939 .332 18 Chipper Jones 1999 .319 45 Aramis Ramirez 2004 .318 36 Joe Morgan 1976 .320 27 Javier Lopez 2003 .328 43 Ryne Sandberg 1990 .306 40 Tony Perez 1970 .317 40 Eddie Mathews 1959 .306 46 Ron Santo 1964 .313 30 Brandon Phillips 2007 .288 30 Brian McCann 2006 .333 24 Hank Sauer 1954 .288 41 Vada Pinson 1963 .313 22 Fred McGriff 1994 .318 34 Sammy Sosa 2001 .328 64 Frank Robinson 1962 .342 39 Felix Millan 1970 .310 2 Riggs Stephenson 1929 .362 17 Pete Rose 1969 .348 16 Dale Murphy 1987 .295 44 Billy Williams 1970 .322 42 -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1956-08-09

owan Serving the State University of Iowa and the People of Iowa City ~-t-a-b-lls~he--d~j-n-I-~----~F~iv-e~Cc-n~u--a~Co~p-y--------~--~~----------~~----------------~M~e~~~r~o~f~A~s=~~w~t=ed~P~r=e~--~A~P~Le=ascd==:;~W~ir-e--ao-d~P~h-o~to~Se-r-v-lc-r------------------------------~~~------------~Io=w=a~C~il=y,~Io=w=a~,~TMh=u=rsd~a:y~,~A:u:g=US:t~9~,~I~~~ 562 Get Degree$ 'af Summer Comm.enc,ement- . , ,. of , • . I Ie :-":on o~ml 'ty " I indep~dence l Iowa Regents O,ppose AMajor Goal, 'StuBent Building Fee Speaker Says DES MOINES 1.4'1 - A student building Cee suggested Cor support oC Prof. Robert S. Michaelsen, dl· SUI and other state coUege building programs~as opposcd by memo r clor of the SUI School of Re bers oC \he Board of Regent.s Wednesday in appearances before the Iowa Taxation Study Committee. ligion. addressed 600 pectators / The committee is studying methods oC financing thc proposed $55 mil· and 562 graduates In Commence· lion building program Cor SUI, ment exercise in the SUI Field· Iowa State College and Iowa State hOuse W~nes~ay night. Suez Matter Teachers College over a to·year Speaking on "Freedom and Con· , period, No decisions were reached, . Cormlj.Y," Dr. Michaelsen urged Some time ago, a subcommittee graduates to resist "drifting with of the tax study group had sug· Of Life, Death gested, for discussion, that a nat thc current." We need to excrcise building fcc oC $90 a year bc charg· that God·gi\,('/1 frcedom which also ed against studel1ts to pay for h IPI' to make u more human; we Says Eden needed new buildings anticipllted BASS PLAYERS in the SUI O,.cMst,.o ....t ond i1willt tholr tum whll. -

Home Plate: a Private Collection of Important Baseball Memorabilia

RESULTS | NEW YORK | 16 DECEMBER 2020 | FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HOME PLATE: A PRIVATE COLLECTION OF IMPORTANT BASEBALL MEMORABILIA TOTAL: $6,545,625 88% SOLD BY LOT | 95% SOLD BY VALUE Important 1931 Lou Gehrig New York Yankees Professional Model Home Jersey PRICE REALIZED: $1,440,000 New York – Christie’s and Hunt Auctions’ historic sale Home Plate: A Private Collection of Important Baseball Memorabilia achieved a total of $6,545,625 with 88% sold by lot, 95% sold by value. The top lot of the sale was the important 1931 Lou Gehrig New York Yankees professional model home jersey, which achieved $1,440,000. Other top results included a scarce and important Babe Ruth Boston Red Sox Era Professional Model Baseball Bat (c. 1916-18) that sold for $600,000 and a highly important Lou Gehrig document archive from Dr. Paul O'Leary of The Mayo Clinic with relation to "ALS: Lou Gehrig Disease" (c.1939-41), which achieved $450,000. The strong selection of vintage baseball cards was led by the 1909-11 T-206 Ty Cobb card which totaled $437,500. A poignant handwritten letter by Marilyn Monroe to Joe DiMaggio written on the reverse of a dry-cleaning receipt circa 1954, sold for $425,000, above its estimate of $50,000-100,000. Eighteen Presidential baseballs signed by 13 U.S. Presidents were led by a rare, Franklin D. Roosevelt-signed ball which sold for $100,000, more than doubling its high estimate. The selection of artefacts from the 1934 All-Star Tour of Japan was led by a significant and very rare 1934 U.S. -

Estimated Age Effects in Baseball

Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports Volume 4, Issue 1 2008 Article 1 Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair, Yale University Recommended Citation: Fair, Ray C. (2008) "Estimated Age Effects in Baseball," Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 1. DOI: 10.2202/1559-0410.1074 ©2008 American Statistical Association. All rights reserved. Brought to you by | Yale University Library New Haven (Yale University Library New Haven) Authenticated | 172.16.1.226 Download Date | 3/28/12 11:34 PM Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair Abstract Age effects in baseball are estimated in this paper using a nonlinear fixed-effects regression. The sample consists of all players who have played 10 or more "full-time" years in the major leagues between 1921 and 2004. Quadratic improvement is assumed up to a peak-performance age, which is estimated, and then quadratic decline after that, where the two quadratics need not be the same. Each player has his own constant term. The results show that aging effects are larger for pitchers than for batters and larger for baseball than for track and field, running, and swimming events and for chess. There is some evidence that decline rates in baseball have decreased slightly in the more recent period, but they are still generally larger than those for the other events. There are 18 batters out of the sample of 441 whose performances in the second half of their careers noticeably exceed what the model predicts they should have been. All but 3 of these players played from 1990 on. -

Sheet1 Hank Aaron 1959-63 Steve Carlton 1969-73 John Evers 1906

Sheet1 2020 APBA BASEBALL HALL OF FAME SET Hank Aaron 1959-63 Steve Carlton 1969-73 John Evers 1906-10 Billy Hamilton 1891-95 Babe Adams 1909-13 Gary Carter 1980, 1982-85 Buck Ewing 1888-90,92-93 Bucky Harris 1921-25 Pete Alexander 1913-17 Orlando Cepeda 1960-64 Red Faber 1920-24 Gabby Hartnett 1933-37 Dick Allen 1964-68 Frank Chance 1903-07 Bob Feller 1938-41, 1943 Harry Heilmann 1923-27 Robby Alomar 1997-2001 Oscar Charleston Rick Ferrell 1932-36 Rickey Henderson 1981-85 Cap Anson 1886-1890 Jack Chesbro 1901-05 Rollie Fingers 1974-78 Billy Herman 1935-39 Luis Aparicio 1960-64 Fred Clarke 1905-09 Carlton Fisk 1974-78 Keith Hernandez 1978-82 Luke Appling 1933-37 John Clarkson 1887-91 Elmer Flick 1903-07 Orel Hershiser 1985-89 Richie Ashburn 1954-58 Roger Clemens 1986-90 Curt Flood 1961-65 Pete Hill Earl Averill 1932-36 Roberto Clemente 1965-69 Whitey Ford 1961-65 Gil Hodges 1951-55 Jeff Bagwell 1994-98 Ty Cobb 1909-13 Rube Foster Trevor Hoffman 1996-2000 Harold Baines 1982-86 Mickey Cochrane 1930-34 Bill Foster Harry Hooper 1918-22 Frank Baker 1910-14 Rocky Colavito 1958-62 Nellie Fox 1956-59 Rogers Hornsby 1921-25 Beauty Bancroft 1920-24 Eddie Collins 1909-13 Jimmy Foxx 1932-36 Elston Howard 1961-65 Ernie Banks 1955-59 Jimmy Collins 1901-05 John Franco 1984-88 Waite Hoyt 1921-25 Jake Beckley 1890-94 Earle Combs 1927-31 Bill Freehan 1967-71 Carl Hubbell 1932-36 Cool Papa Bell David Cone 1993-97 Frankie Frisch 1923-27 Catfish Hunter 1971-75 Albert Belle 1992-96 Roger Connor 1885-89 Jim "Pud" Galvin 1880-84 Monte Irvin 1950-54 Johnny Bench -

CAWS Career Gauge Measure for Best Players of the Live Ball

A Century of Modern Baseball: 1920 to 2019 The Best Players of the Era Michael Hoban, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus (mathematics) – The City U of NY Author of DEFINING GREATNESS: A Hall of Fame Handbook (2012) “Mike, … I appreciate your using Win Shares for the purpose for which it was intended. …thanks … Bill (James)” Contents Introduction 3 Part 1 - Career Assessment The Win Shares System 12 How to Judge a Career 18 The 250/1800 Benchmark - Jackie Robinson 27 The 180/2400 Benchmark - Pedro and Sandy 30 The 160/1500 Benchmark - Mariano Rivera 33 300 Win Shares - A New “Rule of Thumb” 36 Hall of Fame Elections in the 21st Century 41 Part 2 - The Lists The 21st Century Hall of Famers (36) 48 Modern Players with HOF Numbers at Each Position 52 The Players with HOF Numbers – Not Yet in the Hall (24) 58 The Pitchers with HOF Numbers – Not Yet in the Hall (6) 59 The 152 Best Players of the Modern Era 60 The Complete CAWS Ranking for Position Players 67 The Complete CAWS Ranking for Pitchers 74 The Hall of Famers Who Do Not Have HOF Numbers (52) 78 2 Introduction The year 2019 marks 100 years of “the live-ball era” (that is, modern baseball) – 1920 to 2019. This monograph will examine those individuals who played the majority of their careers during this era and it will indicate who were the best players. As a secondary goal, it will seek to identify “Hall of Fame benchmarks” for position players and pitchers – to indicate whether a particular player appeared to post “HOF numbers” during his on-field career. -

National@ Pastime

================~~==- THE --============== National @ Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY Iftime is a river, justwhere are we now Fifty years from now some of our SABR members of to as we float with the current? Where day will write the history of 1991, as they look backfrom the TNPII have we been? Where may we begoing vantage point of 2041. How will we and our world look to on this journey? their grandchildren, who will read those histories? What I thought itwould be fun to take readings ofour position stories will they cover-RickeyHenderson and Nolan Ryan? by looking at where ourgame, and by extension, our coun Jose Canseco and Cecil Fielder?TheTwins and the Braves? try, and our world were one, two, three, and more Toronto's 4 million fans? Whatthings do we take for granted generations ago. that they will find quaint? Whatkind ofgame will the fans of Mark Twain once wrote that biography is a matter of that future world be seeing? What kind of world, beyond placing lamps atintervals along a person's life. He meantthat sports, will they live in? no biographercan completely illuminate the entire story. But It's to today's young people, the historians of tomorrow, ifwe use his metaphor and place lamps at 25-year intervals and to theirchildren and grandchildren thatwe dedicate this in the biography ofbaseball, we can perhaps more dramati issue-fromthe SABR members of1991 to the SABR mem cally see our progress, which we sometimes lose sight ofin bers of 2041-with prayers that you will read it in a world a day-by-day or year-by-year narrative history.