Games for a New Climate: Experiencing the Complexity of Future Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God Games’, with the Player Supposedly Given Omnipotent Control Over the Game Environment, Revealing the Enduring Presence of the Second-Creation Narrative

Smith, B. T. L. (2017). Resources, Scenarios, Agency: Environmental Computer Games. Ecozon@, 8(2), 103-120. http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1365 Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Universidad de Alcale at http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1365 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Resources, scenarios, agency: environmental computer games Abstract In this paper I argue that computer games have the potential to offer spaces for ecological reflection, critique, and engagement. However, in many computer games, elements of the games’ procedural rhetoric limit this potential. In his account of American foundation narratives, environmental historian David Nye notes that the ‘second-creation’ narratives that he identifies “retain widespread attention [...] children play computer games such as Sim City, which invite them to create new communities from scratch in an empty virtual landscape…a malleable, empty space implicitly organized by a grid” (Nye, 2003). I begin by showing how grid-based resource management games encode a set of narratives in which nature is the location of resources to be extracted and used. I then examine the climate change game Fate of the World (2011), drawing it into comparison with game-like online policy tools such as the UK Department for Energy and Climate Change’s 2050 Calculator, and models such as the environmental scenario generation tool Foreseer. -

7:30 A.M. – AUDIT CONFERENCE PARK COMMISSIONERS and PARK DISTRICT AUDIT COMMITTEE (Pursuant to Section 121.22 (D) (2) of the Ohio Revised Code)

BOARD OF PARK COMMISSIONERS OF THE CLEVELAND METROPOLITAN PARK DISTRICT THURSDAY, MARCH 14, 2019 Cleveland Metroparks Administrative Offices Rzepka Board Room 4101 Fulton Parkway Cleveland, Ohio 44144 7:30 A.M. – AUDIT CONFERENCE PARK COMMISSIONERS AND PARK DISTRICT AUDIT COMMITTEE (Pursuant to Section 121.22 (D) (2) of the Ohio Revised Code) 8:00 A.M. – REGULAR MEETING AGENDA 1. ROLL CALL 2. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 3. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING FOR APPROVAL OR AMENDMENT • Regular Meeting of February 14, 2019 Page 88339 4. FINANCIAL REPORT Page 01 5. NEW BUSINESS/CEO’S REPORT a. APPROVAL OF ACTION ITEMS i) General Action Items (a) Chief Executive Officer’s Retiring Guest(s): • Terry L. Robison, Director of Natural Resources Page 07 • Stephen J. Schulz, Education Specialist Page 08 • Virginia G. Viscomi, Service Maintenance II Page 08 (b) 2019 Budget Adjustment No. 2 Page 09 (c) Revision of Rates and User Fees Page 10 (d) Club Metro 2019 Financial Request Page 10 (e) RFP #6149: Golf Cars Page 11 (f) Edgewater Marina Operations – Lease Agreement Page 12 (g) Whiskey Island Marina Operations – Management Services Agreement Page 14 (h) Branded Product Sponsor and Suppler of Beverages Agreement – Page 15 Amendment No. 2 (i) Contract Amendment – RFP #6344-B: Bonnie Park Ecological Restoration Page 16 and Site Improvement Project – Mill Stream Run Reservation -GMP 1 (j) Professional Services Agreement – RFQu #6402: Bridge Inspection and Page 18 Engineering Support Program 2019-2014; and 2020 Bridge Inspections and Summary Reports Proposal (k) Authorization of Funds – Whiskey Island Marina Emergency Repair – Page 21 Wind Damage (l) Nomination of Joseph V. -

DEMO Magazine

ISSUE 18 SPRING/SUMMER 2013 DEMOThe Alumni Magazine of Columbia College Chicago The avant-garde fashion designs of AGNES HAMERLIK Revitalizing Detroit with PHILLIP COOLEY Lessons learned on KICKSTARTER May 17, 2013 ALUMNI AT Want to perform? Volunteer? Or just come out and be a part of the awesome Manifest audience? If you are an alumnus and would like an application to perform on the Alumni Stage, contact Cyn Vargas at [email protected]. Stop by, sit back, and ALUMNI LOUNGE relax in our alumni ALUMNI & lounge! You'll enjoy your Noon – 7PM fellow alumni performers GRADUATION PARTY singing, reciting, dancing, 623 South Wabash and other cool stuff. 8PM – 11PM Quincy Wong Center Hilton Chicago for Artistic Expression 720 S. Michigan Ave. Grand Ballroom colum.edu/alumnimanifest Art: Thumy Phan, Manifest Creative Director Creative Phan, Manifest Art: Thumy ’12) Jacob Boll (BA Photos: CONTENTS DEMO ISSUE 18 SPRING/SUMMER 2013 18 11 FEATURES PORTFOLIO SPOT ON DEpaRTMENTS 8 22 30 Justin “Nordic Thunder” 03 Vision A question for Howard (BA ’07) reigns as President Carter KICKSTART MY ART LIFE DURING king in the competitive world Columbia alumni, students, WARTIME of air guitar. 04 Wire News from the and faculty share lessons Photographer Andrew Nelles Columbia community learned on their way to crowd- (BA ’08) recounts his days 32 Karine Saporta (BA ’72), funding success. covering American troops in knighted in France, 38 Alumni News & Notes By Stephanie Ewing (MA ’12) Afghanistan. As told to Andrew stays in demand as a Featuring class news, notes, Greiner (BA ’05) dancer, choreographer, and networking 14 and photographer. -

Vlaams Audiovisueel Fonds

VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS . jaarverslag 2018 VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS . jaarverslag 2018 uitgegeven door het .VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS vzw huis van de vlaamse film bischoffsheimlaan 38 - 1000 brussel [email protected] vaf.be Met de steun van de Vlaamse minister van Cultuur, Media, Jeugd en Brussel en de Vlaamse minister van Onderwijs INHOUD . jaarverslag 2018 VOORWOORDEN FINANCIEEL CREATIE TALENT- ONTWIKKELING •4 •7 •15 •26 COMMUNICATIE & PUBLIEKSWERKING GAMEFONDS SCREEN PROMOTIE FLANDERS •39 •47 •53 •67 DUURZAAM KENNISOPBOUW WERKING VLAAMSE FILM FILMEN IN CIJFERS •73 •77 •81 •89 Toen ik in mei vorig jaar op het Festival Deze maatregelen zullen ongetwijfeld om op dit vlak lessen te trekken. van Cannes de film Girl te zien kreeg, hun vruchten afwerpen. Toch wil ik een Het is duidelijk dat we erin geslaagd zijn voelde ik aan de stilte in de zaal bij warme oproep doen aan de volgende om ook dit jaar als VAF op verschillende de aftiteling welke magie er uitging Vlaamse Regering voor extra middelen vlakken toonaangevend te zijn. Hopelijk VOORWOORD van het brengen van zo’n mooi en in de nieuwe bestuursperiode. Er kunnen we in de toekomst op dit elan ontroerend verhaal. De tsunami aan werden in het verleden reeds extra doorgaan. Met het huidige team van Alles start met een prijzen die de film in ontvangst mocht middelen vrijgemaakt voor het VAF/ medewerkers heb ik er als voorzitter nemen, was ongezien. We mogen als Mediafonds en het VAF/Gamefonds die alvast het volste vertrouwen in. n goed verhaal VAF bijzonder fier zijn dat we mee aan zeker een boost gegeven hebben. -

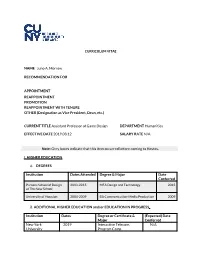

NAME Juno A. Morrow RECOMMENDATION FOR

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Juno A. Morrow RECOMMENDATION FOR APPOINTMENT REAPPOINTMENT PROMOTION REAPPOINTMENT WITH TENURE OTHER (Designation as Vice President, Dean, etc.) CURRENT TITLE Assistant Professor of Game Design DEPARTMENT Humanities EFFECTIVE DATE 2019.08.12 SALARY RATE N/A Note: Grey boxes indicate that this item occurred before coming to Hostos. I. HIGHER EDUCATION A. DEGREES Institution Dates Attended Degree & Major Date Conferred Parsons School of Design 2013-2015 MFA Design and Technology 2015 at The New School University of Houston 2004-2009 BA Communication-Media Production 2009 B. ADDITIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION and/or EDUCATION IN PROGRESS Institution Dates Degree or Certificate & (Expected) Date Major Conferred New York 2019 Interactive Telecom. N/A University Program Camp II. EXPERIENCE A. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Institution Department Rank Dates CUNY—Eugenio María de Hostos Humanities Assistant Professor 2015- Community College Present Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Technology Part-time Lecturer 2015 Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Technology Teaching Fellow 2014 Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Teaching Assistant 2014 Technology B. OTHER EXPERIENCE Institution Department Rank or title role Dates (Independent/Freelance) N/A Photographer/Designer 2009- Present Try The World N/A Front-End Web Developer 2015 Parsons School of Design gadgITERATION Graduate Research 2014-2015 Assistant Reed Elsevier Universal Access Research Coordinator 2012-2013 HASH magazine Photography Staff Photographer 2012-2013 HRP/CoxReps -

Annual Report 2012

BRINGING How we have performed KNOWLEDGE FIN ANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS • Record adjusted diluted EPS up 7.7% to 40.7p (2011: 37.8p), ahead of market expectations TO LIFE • Full year dividend increased by 10.1% – second interim dividend of 12.5p giving a total 2012 dividend of 18.5p (2011: 16.8p) Businesses, professionals and • Revenue broadly flat despite Robbins Gioia and European academics worldwide turn to Informa Conference disposals – £1.23bn (2011: £1.28bn) for unparalleled knowledge, up-to- • Adjusted operating profit up 4.0% to £349.7m the minute information and highly (2011: £336.2m); organic growth of 2.8% specialist skills and services. • Record adjusted operating margin of 28.4% (2011: 26.4%) Our ability to deliver high quality • Adjusted profit before tax of £317.4m up 7.3% (2011: £295.9m) knowledge and services through • Statutory profit after tax of £90.7m (2011: £74.3m) multiple channels, in dynamic and rapidly changing environments, • Strong cash generation – operating cash flow up 5.7% to £329.0m (2011: £311.2m) makes our offer unique and • Balance sheet strength maintained – net debt/EBITDA extremely valuable to individuals ratio of 2.1 times (2011: 2.1 times) and organisations. OPEAI R T ONAL HIGHLIGHTS • Proactive portfolio management drives significant Annual Report & Financial Statements for the year ended December 31 2012 improvement in the quality of Group earnings • Total product rationalisation reduced Group revenue by 2% • Investment in new products, geo-cloning and platform development • Acquisition of MMPI and Zephyr -

Art Architecture Design New Titles the MIT Press Picturing Science and Engineering Felice C

Art Architecture Design New Titles The MIT Press Picturing Science and Engineering Felice C. Frankel “As we create ever more sophisticated tools to explore the micro and macro universe, it’s easy to become detached from agape understanding and appreciation of what we can’t see, feel, and sense. Felice Frankel’s work brings those worlds within reach, so that we can appreciate not only the technical marvels but also the enormous beauty and infinite variety of creation, both natural and manmade.”—Yo-Yo Ma “With the clarity of an expert and the passion of a true aficionado, Frankel once again proves to be crucial in bridging scientific discovery and public consciousness.” —Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, Architecture & Design, Director, Research & Development, The Museum of Modern Art One of the most powerful ways for scientists to document and communicate their work is through photography. In this book, celebrated science photographer Felice Frankel offers a guide for creating science images that are both accurate and visually stunning. Picturing Science and Engineering provides detailed instructions for making science photographs using the DSLR camera, the flatbed scanner, and the phone camera. The book includes a series of step-by-step case studies, describing how final images were designed for cover submissions and other kinds of visualizations. Lavishly illustrated in color throughout, the book encourages the reader to learn by doing, following Frankel as she recreates the stages of discovery that lead to a good science visual. Felice C. Frankel is an award-winning science photographer whose photographs have appeared in many publications. A research scientist in the Department of Chemical Engineering at MIT, she is the author of Envisioning Science (MIT Press), No Small Matter (with G. -

The Internet As Playground and Factory November 12–14, 2009 at the New School, New York City

FIRST IN A SERIES OF BIENNIAL CONFERENCES ABOUT THE POLITICS OF DIGITAL MEDIA THE INTERNET AS PLAYGROUND AND FACTORY NOVEMBER 12–14, 2009 AT THE NEW SCHOOL, NEW YORK CITY www.digitallabor.org The conference is sponsored by Eugene Lang College The New School for Liberal Arts and presented in cooperation with the Center for Transformative Media at Parsons The New School for Design, Yale Information Society Project, 16 Beaver Group, The New School for Social Research, The Change You Want To See, The Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New York University’s Council for Media and Culture, and n+1 Magazine. Acknowledgements General Event Support Lula Brown, Alison Campbell, Alex Cline, Conference Director Patrick Fannon, Keith Higgons, Geoff Trebor Scholz Kim, Ellen-Maria Leijonhufvud, Stephanie Lotshaw, Brie Manakul, Lindsey Medeiros, Executive Conference Production Farah Momin, Heather Potts, Katharine Trebor Scholz, Larry Jackson Relth, Jesse Ricke, Joumana Seikaly, Ndelea Simama, Andre Singleton, Lisa Conference Production Taber, Yamberlie Tavarez, Brandon Tonner- Deepthie Welaratna, Farah Momin, Connolly, Jolita Valakaite, Cynthia Wang, Julia P. Carrillo Deepthi Welaratna, Tatiana Zwerling Production of Video Series Voices from Registration Staff The Internet as Playground and Factory Alison Campbell, Alex Cline, Keith Higgons, Assal Ghawami Geoff Kim, Stephanie Lotshaw, Brie Manakul, Overture Video Lindsey Medeiros, Heather Potts, Jesse Assal Ghawami Ricke, Joumana Seikaly, Andre Singleton, Deepthi Welaratna, Tatiana Zwerling Video -

Game Changer: Investing in Digital Play to Advance Children’S Learning and Health, New York: the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop

Game 2 changer: June 2009 Investing in digital play to advance children's learning and health Ann My Thai David Lowenstein Dixie Ching David Rejeski The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop © The Joan Ganz Cooney Center !""#. All rights reserved. The mission of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop is to foster innovation in children’s learning through digital media. The Center supports action research, encourages partnerships to connect child development experts and educators with interactive media and technology leaders, and mobilizes public and private investment in promising and proven new media technologies for children. For more information, visit www.joanganzcooneycenter.org. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center is committed to disseminating useful and timely research. Working closely with our Cooney Fellows, national advisers, media scholars, and practitioners, the Center publishes industry, policy, and research briefs examining key issues in the $eld of digital media and learning. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.joanganzcooneycenter.org. Individual print copies of this publication are available for %&' via check, money order, or purchase order sent to the address below. Bulk-rate prices are available on request. For permission to reproduce excerpts from this report, please contact: Attn: Publications Department The Joan Ganz Cooney Center Sesame Workshop One Lincoln Plaza New York, NY &""!( p: !&! '#' ()'* f: !&! +,' ,("+ [email protected] Suggested citation: Thai, A., Lowenstein, D., Ching, D., & Rejeski, D. -

The EBRARY Platform

One eContent platform. Many ways to use it. Subscribe, Purchase or Customize Share, Archive & Distribute Integrate THE EBRARY PLatFORM Our eContent Your eContent eBooks, reports, journals, Theses, dissertations, images, journals, sheet music, and more eBooks – anything in PDF Subscribe Purchase Customize Share Archive Distribute SULAIR Select Collections SUL EBRARY COLLECTIONS Select Collections TABLE OF CONTENTS Infotools All ebrary Collections CONTRIBUTORS Byron Hoyt Sheet Music (Browse) INTRODUCTION Immigration Commision Reports (Dillingham) Contents BUSINESS: A USER’S GUIDE Women and Child Wage Earners in the U.S. CSLI Linguistics and Philosophy BEST PRACTICE SUL Books in the Public Domain MANAGEMENT CHECKLISTS Medieval and Modern Thought Text Project ACTIONLISTS MANAGEMENT LIBRARY BUSINESS THINKERS AND MANA DICTIONARY WORLD BUSINESS ALMANAC Highlights Notes BUSINESS INFORMATION SOURC INDEX CREDITS InfoTools Integrates Define Explain Locate multiple online Translate Search Document... resources Search All Documents... Search Web Search Catalog with one Highlight Add to Bookshelf customizable Copy Text... Copy Bookmark interface. Print... Print Again Toggle Automenu Preferences... Help About ebrary Reader... EASY TO USE. Subscribe, Purchase AFFORDABLE. or Customize your ALW ay S AVAILABLE. eBook selection NO CHECK-OUTS. Un I Q U E S U B SC R I B E T O G R OWI ng E B O O K D ataba S E S W I T H SIMULtanEOUS, MULTI-USER ACCESS. RESEARCH TOOLS. ACADEMIC DATABASES Academic Complete includes all academic databases listed below. FREE MARCS. # of # of Subject Titles* Subject Titles* Business & Economics 6,300 Language, Literature 3,400 & Linguistics “ebrary’s content is Computers & IT 2,800 Law, International Relations 3,800 multidisciplinary and Education 2,300 & Public Policy Engineering & Technology 3,700 supports our expanding Life Sciences 2,000 (includes Biotechnolgy, History & Political Science 4,800 Agriculture, and (also includes a bonus selection faculty and curriculum. -

UPDATED Activate Outlook 2021 FINAL DISTRIBUTION Dec

ACTIVATE TECHNOLOGY & MEDIA OUTLOOK 2021 www.activate.com Activate growth. Own the future. Technology. Internet. Media. Entertainment. These are the industries we’ve shaped, but the future is where we live. Activate Consulting helps technology and media companies drive revenue growth, identify new strategic opportunities, and position their businesses for the future. As the leading management consulting firm for these industries, we know what success looks like because we’ve helped our clients achieve it in the key areas that will impact their top and bottom lines: • Strategy • Go-to-market • Digital strategy • Marketing optimization • Strategic due diligence • Salesforce activation • M&A-led growth • Pricing Together, we can help you grow faster than the market and smarter than the competition. GET IN TOUCH: www.activate.com Michael J. Wolf Seref Turkmenoglu New York [email protected] [email protected] 212 316 4444 12 Takeaways from the Activate Technology & Media Outlook 2021 Time and Attention: The entire growth curve for consumer time spent with technology and media has shifted upwards and will be sustained at a higher level than ever before, opening up new opportunities. Video Games: Gaming is the new technology paradigm as most digital activities (e.g. search, social, shopping, live events) will increasingly take place inside of gaming. All of the major technology platforms will expand their presence in the gaming stack, leading to a new wave of mergers and technology investments. AR/VR: Augmented reality and virtual reality are on the verge of widespread adoption as headset sales take off and use cases expand beyond gaming into other consumer digital activities and enterprise functionality. -

June 2009 University of Illinois at Chicago, School of Art and Design

LINDSAY D. GRACE | PROFESSORGRACE.COM EDUCATION June 2009 University of Illinois at Chicago, School of Art and Design Master of Fine Art, Electronic Visualization (focus: interactive systems) Grade Point Average: 3.75/4.0 September 2005-January 2007 University of Illinois at Chicago, School of Engineering Ph.D. Computer Science, Electronic Visualization Lab (degree not completed-chose to pursue MFA) August 2003 Northwestern University, School of Engineering Master of Science in Computer Information Systems Grade point average: 3.94 / 4.0 June 1998 Northwestern University, College of Arts and Science B.A. in English with a concentration in Drama ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE: August 2018-present University of Miami, Miami, FL Knight Chair in Interactive Media and Associate Professor School of Communication § Conduct and support research at the apex of journalism and interactive media, create new courses in eSports, game studies and varied initiatives. June 2014-August 2018 American University Game Lab Studio, Washington, DC Director § Found and direct independent academic game studio, providing creative and strategic leadership for a portfolio in excess of $850,000+ in contracts between 2014-2018. Clients include the World Bank, WGBH-Boston, Education Testing Services (ETS), National Institutes of Mental Health, et al. Funders include James L and John S. Knight Foundation and the Institute of Museum and Library Sciences (IMLS) § Direct architects and interior designers for construction of new 2800 square ft game facility (1 classroom, open format