2. Consolidation Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Wanna Be Me”

Introduction The Sex Pistols’ “I Wanna Be Me” It gave us an identity. —Tom Petty on Beatlemania Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being. —Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition here fortune tellers sometimes read tea leaves as omens of things to come, there are now professionals who scrutinize songs, films, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular culture for what they reveal about the politics and the feel W of daily life at the time of their production. Instead of being consumed, they are historical artifacts to be studied and “read.” Or at least that is a common approach within cultural studies. But dated pop artifacts have another, living function. Throughout much of 1973 and early 1974, several working- class teens from west London’s Shepherd’s Bush district struggled to become a rock band. Like tens of thousands of such groups over the years, they learned to play together by copying older songs that they all liked. For guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook, that meant the short, sharp rock songs of London bands like the Small Faces, the Kinks, and the Who. Most of the songs had been hits seven to ten 1 2 Introduction years earlier. They also learned some more current material, much of it associated with the band that succeeded the Small Faces, the brash “lad’s” rock of Rod Stewart’s version of the Faces. Ironically, the Rod Stewart songs they struggled to learn weren’t Rod Stewart songs at all. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Quantum Leap Stormdrum 3 Manual

Quantum Leap Stormdrum 3 Virtual Instrument Users’ Manual QUANTUM LEAP STORMDRUM 3 VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not rep- resent a commitment on the part of East West Sounds, Inc. The software and sounds described in this document are subject to License Agreements and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by East West Sounds, Inc. All product and company names are ™ or ® trademarks of their respective owners. Solid State Logic (SSL) Channel Strip, Transient Shaper, and Stereo Compressor licensed from Solid State Logic. SSL and Solid State Logic are registered trademarks of Red Lion 49 Ltd. © East West Sounds, Inc., 2013. All rights reserved. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA 1-323-957-6969 voice 1-323-957-6966 fax For questions about licensing of products: [email protected] For more general information about products: [email protected] http://support.soundsonline.com ii QUANTUM LEAP STORMDRUM 3 VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT 1. Welcome 2 About EastWest and Quantum Leap 3 Producer: Nick Phoenix 4 Percussionist: Mickey Hart 5 Credits 6 How to Use This and the Other Manuals 7 Online Documentation and Other Resources Click on this text to open the Master Navigation Document 1 QUANTUM LEAP STORMDRUM 3 VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT Welcome About EastWest and Quantum Leap Founder and producer Doug Rogers has over 35 years experience in the audio industry and is the recipient of many recording industry awards including “Recording Engineer of the Year.” In 2005, “The Art of Digital Music” named him one of “56 Visionary Artists & Insiders” in the book of the same name. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

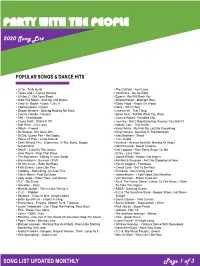

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Immigrant Musicians on the New York Jazz Scene by Ofer Gazit A

Sounds Like Home: Immigrant Musicians on the New York Jazz Scene By Ofer Gazit A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Benjamin Brinner, Chair Professor Jocelyne Guilbault Professor George Lewis Professor Scott Saul Summer 2016 Abstract Sounds Like Home: Immigrant Musicians On the New York Jazz Scene By Ofer Gazit Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Benjamin Brinner, Chair At a time of mass migration and growing xenophobia, what can we learn about the reception, incorporation, and alienation of immigrants in American society from listening to the ways they perform jazz, the ‘national music’ of their new host country? Ethnographies of contemporary migrations emphasize the palpable presence of national borders and social boundaries in the everyday life of immigrants. Ethnomusicological literature on migrant and border musics has focused primarily on the role of music in evoking a sense of home and expressing group identity and solidarity in the face of assimilation. In jazz scholarship, the articulation and crossing of genre boundaries has been tied to jazz as a symbol of national cultural identity, both in the U.S and in jazz scenes around the world. While these works cover important aspects of the relationship between nationalism, immigration and music, the role of jazz in facilitating the crossing of national borders and blurring social boundaries between immigrant and native-born musicians in the U.S. has received relatively little attention to date. -

From Guy Warren to Kofi Ghanaba: a Life of Transatlantic (Dis)Connections

Individual Life From Guy Warren to Kofi Ghanaba: A Life of Transatlantic (Dis)Connections Robin D. G. Kelley “ here has never been anybody in the history of Jazz music like me . I am Tto Jazz music what Kwame Nkrumah was to modern African politics.”1 These bold words belong to the late Kofi Ghanaba, the Ghanaian-born drum- mer who pioneered jazz-African fusion music during the era of decolonization. Anyone familiar with Ghanaba and his music, whether as the wise African in Haile Gerima’s celebrated film “Sankofa,” or as the young, dynamic percussion- ist Guy Warren who had taken London, Chicago, and New York by storm in the 1950s, will immediately recognize his legendary hubris. But there is a grain of truth here beyond his conceit. Their lives might be read as parallel stories of two important Ghanaian-born intellectuals whose transatlantic travels between the United States, the United Kingdom, and West Africa profoundly shaped their politics, ideas, and identities. Both men studied at Achimota College in the Gold Coast; both men spent time in the United Kingdom where they encountered an African diasporic community whose politics and art widened their horizons; and both men spent several years in the United States, which they initially envi- sioned as a land of freedom and possibility in an era when the United Kingdom’s imperial fortunes were declining and the so-called American Century was beginning. Nkrumah first arrived in London in 1935, just after Italy invaded Ethiopia. Although he was passing through en route to the United States, Nkrumah fell in with a group of like-minded activists mobilizing against the occupation and demanding that the League of Nations protect Ethiopia’s sovereignty. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Model Music Curriculum: Key Stages 1 to 3 Non-Statutory Guidance for the National Curriculum in England

Model Music Curriculum: Key Stages 1 to 3 Non-statutory guidance for the national curriculum in England March 2021 Foreword If it hadn’t been for the classical music played before assemblies at my primary school or the years spent in school and church choirs, I doubt that the joy I experience listening to a wide variety of music would have gone much beyond my favourite songs in the UK Top 40. I would have heard the wonderful melodies of Carole King, Elton John and Lennon & McCartney, but would have missed out on the beauty of Handel, Beethoven and Bach, the dexterity of Scott Joplin, the haunting melody of Clara Schumann’s Piano Trio in G, evocations of America by Dvořák and Gershwin and the tingling mysticism of Allegri’s Miserere. The Model Music Curriculum is designed to introduce the next generation to a broad repertoire of music from the Western Classical tradition, and to the best popular music and music from around the world. This curriculum is built from the experience of schools that already teach a demanding and rich music curriculum, produced by an expert writing team led by ABRSM and informed by a panel of experts – great teachers and musicians alike – and chaired by Veronica Wadley. I would like to thank all involved in producing and contributing to this important resource. It is designed to assist rather than to prescribe, providing a benchmark to help teachers, school leaders and curriculum designers make sure every music lesson is of the highest quality. In setting out a clearly sequenced and ambitious approach to music teaching, this curriculum provides a roadmap to introduce pupils to the delights and disciplines of music, helping them to appreciate and understand the works of the musical giants of the past, while also equipping them with the technical skills and creativity to compose and perform. -

Adf Musicians Live in Concert

Presents ADF MUSICIANS LIVE IN CONCERT Adam Crawley Jeff Dalby Andy Hasenpflug Terrence Karn Amadou Kouyate Eric Mullis West Oxking Sherone Price Atiba Rorie Khalid Saleem Del Ward Tuesday, July 7 at 7:00pm Live Stream While My Bellows Gently Squeeze Composed and performed by Terrence Karn From A to B, Through C, avoiding D wherever possible Composed by Adam Crawley Performed by DJ Plie She Said Darlin You Don’t Know Nothin at All Composed by Jefferson Dalby Performed by Jeff Dalby Music for the Majestic Kora Selected and performed by Amadou Kouyate If You Were Coming in the Fall Composed and performed by Andy Hasenpflug Poetry: If You Were Coming in the Fall by Emily Dickinson Conditions Composed and performed by Del Ward The Rhythm Collective Composed and performed by Khalid Saleem, Atiba Rorie, Sherone Price, and friends The Most Originally Mine Composed and performed by Eric Mullis For Joy Davis Mammaw’s House Composed by Jefferson Dalby Performed by Jeff Dalby El Color de la Paz Composed and performed by West Oxking ADAM CRAWLEY is a musician from Muncie, IN, where he composes, accompanies, teaches, and performs in the dance department at Ball State University. His music can be found on most streaming platforms with a more complete library and contact information at DjPlie.com. He has been a part of the ADF community since 2013 as well as working with other festivals, companies, and individuals nationwide. A relic of the past, JEFF DALBY has accompanied Daniel Nagrin, Ruth Currier, James Truitte, Violette Verdy, and Erik Bruhn.