Soil Report 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report

9th -11th November, 2017 India Expo Mart (IEML) Greater Noida, U.P. (Delhi – NCR), India biofach-india.com FINAL REPORT International patron: Co-organizer: Organizer: Final Report Exhibition name: BIOFACH INDIA together with INDIA ORGANIC 2017 Venue: India Expo Mart Limited (IEML) Greater Noida, U.P., Delhi-NCR, India Date: November 9 - 11, 2017 Organizer: Co-Organizer: International Patron: Contacts for exhibition: Ms. Priya Sharma Project Director T: +91 (0) 11 4716 8830 Email: [email protected] Ms. Tanya Bhardwaj Project Manager T: +91 (0) 11 4716 8826 Email: [email protected] Save the date for BIOFACH INDIA 2018: October 25 - 27, 2018 Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, India To book exhibition space in 2018, please contact one of the representatives mentioned above. www.biofach-india.com Page 2 of 15 Final Report FACTS & FIGURES Gross Space 4000 sqm Exhibitors 184 State Pavilions 17 Indian States participated at the Show Andhra Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh Assam, Bihar Chattisgarh Karnataka Kerala Maharashtra Manipur Meghalaya Nagaland Punjab Sikkim Telangana Tripura Uttarakhand Uttar Pradesh Congress Participants / Congress Participants – 2479 Visitors Trade Visitors ( including farmer groups) 7175 www.biofach-india.com Page 3 of 15 Final Report AN OUTSTANDING EDITION OF BIOFACH INDIA 2017! The ninth edition of India’s largest and most focused event for country, India won the bid to host the event this year against organic products concluded successfully. The fair provided the stiff competition from Russia, China and Brazil. The Organic perfect business platform to organic stakeholders, retailers, World Congress once again played a critical role in strength- exporters / importers, Govt. -

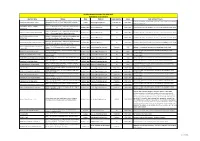

Operator Name Category Country Scope 1 Scope 2 Scope 3 Product Category Address Primary Contact E-Mail Status Plot No

Enlisted certified operations have been certified to OneCert International Organic Standards-Equivalent to EC 834/2007. This list includes certified operations as of February 12, 2020 Please contact [email protected] for information on decertified, suspended, surrendered and revoked operations. Operator Name Category Country Scope 1 Scope 2 Scope 3 Product Category Address Primary Contact E-mail Status Plot No. 3312/18, Phase IV Chhatral GIDC, Taluka-Kalol Amrutva Fine Foods LLP D India Handling Oils & Pastes Hitesh Chotalia [email protected] Certified Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382729 Doi Thong Community Enterprise for Coffee, fruits, nuts, spices A, D Thailand Crop Handling 100 M. 7 T. Doi Kaew, Chomthong District, Chiang Mai 50160 Phanuwat Mongkhon [email protected] Development (Coffee Project) & herbs Certified Doi Thong Community Enterprise for A Thailand Crop Herbs, fruits & vegetables 100 M. 7 T. Doi Kaew, Chomthong District, Chiang Mai 50160 [email protected] Development (Longan Project) Phanuwat Mongkhon Certified Doi Thong Community Enterprise for 101/2 M. 7 T. Doi Kaew, Chomthong District, Chiang Mai A Thailand Crop Rice, Fruits, Herbs, Wheat [email protected] Development (Rice Project) 50160 Phanuwat Mongkhon Certified Spices, Oils & Herbal Kulayan Natural Herbal Pvt Ltd A, D, A Nepal Crop Handling Wild Harvest Mechinagar-10, Kakarbhitta, Bhadrapur, Jhapa District Mukesh Basnet [email protected], Certified Extracts Essential Oils & Herbal [email protected], Khaptar Aroma Industries D, A Nepal Handling Wild Harvest Namua Ga Bi Sa, Godawai Ward No. 1 Lalitpur Certified Extracts Samir Dhangel [email protected], House no-12 A, Arvind Vihar, Baghmugaliya,Bhopal,Madhya Vandana Organic Trade OPC Pvt. -

Central Institute of Post Harvest Engineering & Technology Ludhiana

Central Institute of Post Harvest Engineering & Technology Ludhiana Our Slogan: Produce, Process and Prosper CIPHET E – Newsletter for September, 2009 Vol. 4 No. 9 Director’s Column Dear All, CIPHET family joins rest of the world in expressing our sorrow and condolences on the sad demise of Prof. Norman Borlaug, father of green revolution in India and whose discoveries have been estimated to have saved over one billion lives worldwide. The major event this month was transfer of the technology of Pomegranate Aril Extractor for commercial manufacture. We have been receiving requests for hand tool as well as for motorized machine from different parts of the country as well as from abroad and licensing of manufacturing to a firm will make available machines for commercial use. The National Seminar on “Nutritional Strategies for Improving Quality of Life” was held GBPUA&T, Pantnagar. The Food and Nutrition Security of the growing population is a multi-disciplinary task and we all have to concentrate on conducting useful research on the crop commodities we grow. The example of voluminous processing research in case of wheat, rice and soybean versus little research on hundreds of our precious commodities like ber, pomegranate, amla, and millets should be an eye opener for us. I was invited for inauguration of Agricultural Technology Week, which was celebrated by Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Nandurbar in Maharashtra. It is very good initiative started by Extension Division of Indian Council of Agricultural Research at all its KVKs. The KVK Nandurbar has been doing excellent work introducing new crops, production techniques, mechanization in production agriculture, developing and storing quality seeds with farmer participation etc. -

[Harnessing the Power of Technology for Blended Value Creation

[HARNESSING THE POWER OF TECHNOLOGY FOR BLENDED VALUE CREATION A CONTEXTUAL AND PRACTICAL ANALYSIS OF TECHNOLOGY-RELATED SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP VENTURES] Daphne Leger SENIOR CAPSTONE ADVISOR: NANETTE LEVINSON UNIVERSITY HONORS IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES AMERICAN UNIVERSITY SPRING 2008 L e g e r | 1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................... 2 PART 1: CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS ................................................................. 3 1.1 Social Entrepreneurship.................................................................................................3 1.2 The Bottom of the Pyramid.............................................................................................4 1.3 For-Profit Social Entrepreneurship ...............................................................................6 1.4 Need for Technology in Development............................................................................8 1.5 Best Practices and Success Factors ................................................................................9 1.6 Challenges for Technology Ventures ..........................................................................11 1.7 Conclusions ...................................................................................................................12 PART 2: CASE STUDY...................................................................................... 15 2.1 Environmental Assessment...........................................................................................15 -

Organic Yellow Pages Esvasa

2nd Edition India’s Largest Information Hub for Organic Food & Lifestyle eSvasa Organic Yellow Pages India’s Guide to all things Organic Partners Connect with us at www.eSvasa.com or email us at [email protected] Disclaimer and Terms & Conditions This is the 2nd edition of the eSvasa Yellow Pages (referred to as eYP2), and is published in 2014. The eYP2 contains information and advertisements provided by third parties & collected by eSvasa through email, reliable contacts, internet research and personal field trips. Despite best efforts, and attempts to verify all the data, there may be typographical or other errors, technical inaccuracies, programming bugs or viruses, or any other types of inadequacies in the paper or digital format of the eYP2. eSvasa reserves the right to edit/ include/ exclude any information about businesses sent to us/ or taken from our research sources, to make it compatible with the eSvasa Yellow Pages. In case any organic stakeholder has inadvertently been left out/ omitted, we would try and accommodate them in the reprint/ next edition, as feasible. The information is ‘as is’, and the reader should use his/ her own judgement & exercise due diligence while connecting with any listed parties. Readers are strongly advised to check the veracity of the listed parties – including their being organic, certified etc as per their own requirement. Please also note that some stores may also have closed down since work started on the eYP2; their listing will be removed asap. Trademarks and copyright violations eSvasa reserves the right to all the data in the eYP2, and no part of the paper or digital eYP2 may be copied, reproduced or transmitted in part or whole by any means without the permission of eSvasa. -

For a Healthier Tomorrow F + 91 22 2674 4903 [email protected] [email protected] India Organics Pvt

India Organics Pvt. Ltd. Suminter India Organics Pvt Ltd X Cube Building, 3rd Floor New Link Road, Andheri (West) Mumbai 400 053. India Works: Bergwerff Organic India Pvt Ltd C 36/38, SEZ Phase 1, Sector 3 Pithampur Dist. Dhar, Madhya Pradesh 454 775. India T + 91 22 4202 9000 E [email protected] For a healthier tomorrow F + 91 22 2674 4903 [email protected] [email protected] India Organics Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] www.suminter.com Closed size: w 7” x h 9.5” massive strides green footprints From the sugar in your cookies to the cinnamon in your apple pie, Suminter’s products touch the lives of millions of consumers in endless ways, every day. Suminter India Organics was built on the idea of creating an efficient bridge between small farmers in India and buyers across Safer Products the world seeking high-quality organic produce. What started out as a small Happier Farmers trading company sourcing and supplying organic produce from India to buyers A Healthier Planet internationally, is today one of India’s leading exporters with an exhaustive range of 100% organic products. Our Products Organic Spices Mace * Cloves TBC & CS * Thyme * Organic Oil Seeds Organic Cereals Ajwain Whole Mace Powder * Cardamom TBC & CS * Rosemary * Black Mustard Bold Amaranthus Seeds Arrowroot Powder Nutmeg Powder * Nutmeg TBC & CS * Lemon Grass * Hulled Sesame Seeds Brown Basmati Rice Pusa Black Pepper (Cracked) * Nutmeg w/o Shell * Black Pepper TBC & CS * Centella Asiatica/Brahmi * Natural Sesame Seeds Brown Basmati Rice -

Sir Ratan Tata Trust & Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust

Sir Ratan Tata Trust & Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust Annual Report 2007 - 2008 June 12, 2008 MESSAGE The year 2007-08 saw an amalgamation of the grant initiatives of the Sir Ratan Tata Trust and the Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust, both working towards achieving unified goals. The year also marked the first year of operations under the Strategic Plan 2011, which provides the framework for the Trusts’ grant making operations over the next five year period. Consequently, the combined disbursals of the Trusts during the year touched Rs. 1.11 billion (US $ 27.70 million). Notably, disbursals have been rising appreciably every year, vindicating the Group’s vision of sharing its wealth amidst the disadvantaged sections within India. Disbursals within the Rural Livelihoods & Communities (RLC) portfolio have historically constituted a major proportion vis-à-vis disbursals across other thematic areas. The year under review was no exception, with over 60% of the total grant outlay falling within this portfolio. The Trusts have focused on ‘inclusiveness in growth’ and ‘regaining agricultural relevance’ across grant making efforts within the RLC thematic area, in an attempt to align their goals and ideals with the tenets and national approach of the eleventh Five Year Plan of the nation. The Trusts continued their commitment towards the establishment of the Rs. 2.50 billion cancer hospital in Kolkata, specializing in the detection and treatment of cancer, through an endowment grant of Rs. 250 million, towards building up the corpus of the Tata Medical Centre Trust, responsible for this project. With Rs. 450 million already having being invested by the Trusts towards the Hospital during 2005-06 and 2006-07, their total commitment to date is to the tune of Rs. -

FOOD PROCESSING for Value Addition

JUNE 2021 VOLUME XXIV | ISSUE 06 FOOD PROCESSING For Value Addition June 2021 AGRICULTURE TODAY 1 Contributing with unique solutions to the EcoAgriculture Revolution All AlgaEnergy MicroAlgae solutions India Pvt Ltd products in India Noida One, Unit 216 & 217 are EcoCert Plot No-8, Block-B, Tower C, Sector-62 2 certificated AGRICULTURE TODAY NoidaJune 2021 · India June 2021 +911202975513 · [email protected] From the CEO’s Desk... President Dr. MJ Khan CEO & Group Editor Mamta Jain Group Executive Editor Food Processing - Route to Sustainability Rajni Shaleen Chopra Editor Agri News Food Processing is the transformation of any raw product of Sanjay Kumar agriculture, dairy, meat, poultry or fishing for an escalated commercial and consumption value along with shelf life. The Food Andhra Pradesh Processing Industry (FPI) is of enormous significance as it provides Satish Babu Gadde vital linkages and synergies between the two pillars of the economy, Assam i.e. agriculture and industry. Jyoti Bikash Nath Bihar Food processing has numerous advantages which are specific to Girendra Narayan the Indian context. Haryana · It provides direct and indirect Bijender Singh Dalal Employment Generation: employment opportunities because it acts as a bridge between Himachal Pradesh Agriculture and Industry. Rakesh Kumar · Doubling Farmers’ Income: With value addition through food Karnataka processing, there will be a commensurate rise in the price paid to Santosh Langer Maharashtra the farmer, increasing his income. Pasha Patel · Reduce food wastage: NITI Aayog estimated the annual post- Madhya Pradesh harvest losses of close to Rs 90,000 crore. With greater thrust on Rakesh Dubey proper sorting and grading close to the farm gate, and diverting Punjab extra produce to FPI, this wastage can be reduced, leading to better Puneet Singh Thind price realisation for farmers, e.g. -

Organic Food Guide for Consumers

An ORGANIC FOOD GUIDE FOR CONSUMERS CONSUMER EDUCATION AND RESEARCH CENTRE, AHMEDABAD. INDIA 1 An Organic Food Guide for Consumers Researched and compiled by Consumer Education and Research Centre Ahmedabad, Gujarat Year: 2015 Supported by Consumers International, London 24 Highbury Crescent London N5 1RX United Kingdom Published by Consumer Education and Research Centre "Suraksha Sankool", Thaltej, Sarkhej-Gandhinagar Highway Ahmedabad 380 054 Gujarat (India) Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.cercenvis.nic.in, www.cercindia.org An ORGANIC FOOD GUIDE 2 FOR CONSUMERS Preface he right to safe, healthy, affordable and Consequently, commissioned by CI, London in sustainable food is a fundamental partnership with the Swedish Society for Thuman right. Availability of such food Nature and Conservation (SSNC), CERC becomes even more vital with growing global conducted a detailed study in 2015 for the population and increasing environmental purpose of creating this simple, easy to use concerns. Guide Book that aims to demystify the world of organic foods for consumers in India. The demand for organic foods is increasing in the country especially in urban areas, as Consumer Education and Research Centre people look for healthier, pesticide-free, (CERC), Ahmedabad now has the pleasure of environmentally friendly and sustainable releasing the Guide Book “An Organic Food lifestyle alternatives. Whilst, in part, the Guide for Consumers” under Green Action increase in demand for organic food might Fund (GAF) theme for 2015: Safer, More seem like an up-market fad, for most Sustainable Food for All. consumers of organic foods, the market place offers dilemma and confusion in abundant The Guide aims to help the consumer identify measure. -

TQ CERT ORGANIC CLIENT LIST-2020-2021 Updated As on 31

TQ CERT ORGANIC CLIENT LIST-2020-2021 Updated as on 31-12-2020 Operator Name Address State EMAIL ID Scope Operation Scope Major certified Products Address: Plot No - 1006 B, Laxmi Sagar, Near Khan Chicken Center, Beetroot, foxtail millet, soyabean white, kodo millet, finger millet, barnyard millet, ORGANIC GROWER GROUP - JAJPUR Bhubaneswar,751006, Pin:751006, State: Odisha And District: Odisha [email protected] Production- ICS NPOP & NOP sunflower, turmeric fresh Khordha SARVMANGAL ORGANIC FARMERS Address: 77- Bhaktambar Colony, Radhika Hills, Ahmadabad Road, Madhya Pradesh [email protected] ICS NPOP & NOP Maize(corn other tha seed), soyabean, sunflower seeds, bengal gran whole, wheat ASSOCIATION Pin:454001,State: Madhya Pradesh, And District: Dhar. Address: 77- Bhaktambar Colony, Radhika Hills, Ahmedabad Road, NIRMAL ORGANIC FARMERS ASSOCIATION Madhya Pradesh [email protected] ICS NPOP & NOP Maize(corn other tha seed), soyabean, sunflower seeds, bengal gran whole, wheat Dhar, Pin:454001, State: Madhya Pradesh, District: Dhar NIRMAL JIVAN ORGANIC FARMERS Address: 77- Bhaktambar Colony, Radhika Hills,Ahmadabad Road, Madhya Pradesh [email protected] ICS NPOP & NOP Maize(corn other tha seed), soyabean, sunflower seeds, bengal gran whole, wheat ASSOCIATION Pin:454001,State: Madhya Pradesh And District: Dhar Address: 77- Bhaktambar Colony, Radhika Hills, Ahmadabad Road, MAHI SAGAR ORGANIC FARMERS ASSOCIATION Madhya Pradesh [email protected] ICS NPOP & NOP Maize(corn other tha seed), soyabean, sunflower seeds, bengal gran -

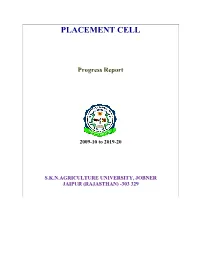

Placement Cell

PLACEMENT CELL Progress Report 2009-10 to 2019-20 S.K.N.AGRICULTURE UNIVERSITY, JOBNER JAIPUR (RAJASTHAN) -303 329 Information of Placement Cell SKNAU, Jobner University has a well established placement cell managed by faculty members. The cell looks after the guidance to the students about job opportunities and higher education in different areas. The cell organizes special lectures, personality development workshops, trainings on communication skills and campus placements. This has been helpful for the students in their placement in different organizations including public and private organization. Placement cell developed online data base of all the students of B.Sc.(Ag) final year/M.Sc(Ag)./ Ph.D. for their placement. Placement of Students (2009-10 to 2019-20) Placement Places Years Total 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013- 2014 2015- 2016 2017 2018 2019 -10 -11 -12 -13 14 -15 16 -17 -18 -19 -20 Government 75 (ARO, AARO, Seed Officer, AAO, Ag. 10 92 06 268 10 90 72 15 15 30 683 Supervisor, NSC, NHB, SFCI, Lab Technician) University/ICAR 6 (Assistant Professor, SMS, SRF/Ag. 07 07 90 40 05 04 03 15 68 84 329 Scientist) IFFCO, RAJEEVIKA - 3 - 06 02 - - 03 04 06 2 26 KRIBHCO,FCI,CWC Banks (Ag. Field Officer) 12 13 12 03 13 30 09 08 16 18 15 149 Private Companies & NGO 32 23 18 10 05 07 23 10 14 01 16 159 Self Farming 09 08 - 05 - 02 10 12 8 10 5 69 Employed Business 02 02 - 01 - 05 03 05 4 05 4 31 Education 40 50 45 50 - 10 14 10 12 09 5 245 Total 194 115 435 119 113 133 81 81 154 137 129 1691 Average package Year Highest Package Average Package 2013 6,00,000/- 5,25,000/- 2014 6,00,000/- 4,60,885/- 2015 6,00,000/- 3,25,000/- 2016 6,00,000/- 3,75,000/- 2017 6,00,000/- 3,75,000/- 2018 6,00,000/- 3,60,000/- 2019 6,00,000/- 3,60,000/- 2020 6,00,000/- 3,60,000/- Name of companies/organization Interacted for Placement of students during 2013-2019 SNo. -

The Indian Organic Food Market

THE INDIAN ORGANIC FOOD MARKET 2 Contents Organic- Concept Statement Global- Organic Farming & Food India- Organic Farming & Food SWOT - Organic Sector Roadmap 3 Definition of “Organic” An Organic label indicates to the consumer that a product was produced using certain production methods. In other words, Organic is a process claim rather than a product claim. The International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), a non-governmental organization, internationally networking and promoting Organic agriculture, has established guidelines that have been widely adopted for Organic production and processing. Codex Committee on Food Labeling has debated "Draft Guidelines for the Production, Processing, Labeling and Marketing of Organically Produced Foods“ for adoption of a single definition for Organic agriculture by the Codex Alimentarius Commission at its meeting in June, 1999. 4 According to the proposed Codex definition, "Organic agriculture is a holistic production management system which promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity. It emphasizes the use of management practices in preference to the use of off-farm inputs, taking into account that regional conditions require locally adapted systems. This is accomplished by using, where possible, agronomic, biological, and mechanical methods, as opposed to using synthetic materials, to fulfill any specific function within the system." 5 Organic Agriculture Organic agriculture systems and products are not always certified and are referred to as “Non-certified Organic agriculture or products". Certified Organic products are generally more expensive than their conventional counterparts for a number of reasons : . Production cost for Organic food is typically higher because of greater labour inputs per unit of output.