Land Title Registration: an English Solution to an American Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nber Working Paper Series De Facto and De Jure Property Rights

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DE FACTO AND DE JURE PROPERTY RIGHTS: LAND SETTLEMENT AND LAND CONFLICT ON THE AUSTRALIAN, BRAZILIAN AND U.S. FRONTIERS Lee J. Alston Edwyna Harris Bernardo Mueller Working Paper 15264 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15264 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2009 For comments we thank Eric Alston, Lee Cronk, Ernesto Dal Bó, John Ferejohn, Stephen Haber, P.J. Hill, Gary Libecap, Henry Smith, Ian Wills and participants at: a seminar on social norms at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton; a conference on “Australian Economic History in the Long Run;” the Research Group on Political Institutions and Economic Policy held at Princeton University; and a seminar at Monash University. Alston and Mueller acknowledge the support of NSF grant #528146. Alston thanks the STEP Program at the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton for their support as a Visiting Research Scholar during 2008/2009 and The Australian National University for support as Research Fellow in 2009. We thank Eric Alston for research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by Lee J. Alston, Edwyna Harris, and Bernardo Mueller. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Mason's Minnesota Statutes 1927

1940 Supplement To Mason's Minnesota Statutes 1927 (1927 to 1940) (Superseding Mason s 1931, 1934, 1936 and 1938 Supplements) Containing the text of the acts of the 1929, 1931, 1933, 1935, 1937 and 1939 General Sessions, and the 1933-34,1935-36, 1936 and 1937 Special Sessions of the Legislature, both new and amendatory, and notes showing repeals, together with annotations from the various courts, state and federal, and the opinions of the Attorney General, construing the constitution, statutes, charters and court rules of Minnesota together with digest of all common law decisions. Edited by William H. Mason Assisted by The Publisher's Editorial Staff MASON PUBLISHING CO. SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA 1940 CH. 64—PLATS §8249 street on a street plat made by and adopted by the plat, or any officer, department, board or bureau of commission. The city council may, however, accept the municipality, may present to the district court a any street not shown on or not corresponding with a petition, duly verified, setting forth that such decision street on an approved subdivision plat or an approved is illegal, in whole or in part, specifying the grounds street plat, provided the ordinance accepting such of the Illegality. Such petition must be presented to street be first submitted to the planning commission the court within thirty days after the filing of the deci- for its approval and, if approved by the commission, sion in the office of the planning commission. be enacted or passed by not less than a majority of Upon the presentation of such petition, the court the entire membership of the council, or, if disapproved may allow a writ of certiorari directed to the planning by the commission, be enacted or passed by not less commission to review such decision of the planning than two-thirds of the entire membership of the city commission and shall prescribe therein the time within council. -

Overreaching: Beneficiaries in Occupation

-The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 188) TRANSFER OF LAND OVERREACHING: BENEFICIARIES IN OCCUPATION Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 December 1989 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE L4.90 net 61 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Right Honourable Lord Justice Beldam, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. OVERREACHING BENEFICIARIES IN OCCUPATION CONTENTS Pa ragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 Background and scope 1.1 1 Recommendations 1.7 2 Structure of this report 1.8 2 PART 11: THE PRESENT LAW 2.1 3 Introductory 2.1 3 Equitable interests 2.3 3 Overreaching 2.9 4 Mortgagees 2.14 5 Personal representatives 2.16 6 Bare trustees 2.17 6 Safeguard for beneficiaries 2.18 7 Registered land 2.2 1 7 Registration of beneficiary’s interests 2.25 8 Beneficiary in occupation: summary 2.28 9 PART 111: NEED FOR REFORM 3.1 10 Change of circumstances 3.1 10 Protecting occupation of property 3.4 10 Bare trusts 3.10 12 PART IV REFORM PROPOSALS 4.1 13 Principal recommendation 4.1 13 Beneficiaries 4.4 13 (a) Interests 4.5 13 (b) Capacity 4.8 14 (c) Occupation 4.11 14 (d) Consent 4.15 15 Conveyances by mortgagees 4.20 16 Conveyances by personal representatives 4.22 16 Conveyances under court order 4.23 17 Conveyancing procedure 4.24 17 Second recommendation: bare trusts 4.27 18 Transitional provisions 4.28 18 Application to the Crown 4.30 18 PART V: SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 5.1 19 APPENDIX A Draft Law of Property (Overreaching) Bill with Explanatory Notes 21 APPENDIX B: Individuals and organisations who com- mented on Working Paper No. -

Patrick John Cosgrove

i o- 1 n wm S3V NUI MAYNOOTH Ollfctel na t-Ciraann W* huatl THE WYNDHAM LAND ACT, 1903: THE FINAL SOLUTION TO THE IRISH LAND QUESTION? by PATRICK JOHN COSGROVE THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr Terence Dooley September 2008 Contents Acknowledgements Abbreviations INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: THE ORIGINS OF THE WYNDHAM LAND BILL, 1903. i. Introduction. ii. T. W. Russell at Clogher, Co. Tyrone, September 1900. iii. The official launch of the compulsory purchase campaign in Ulster. iv. The Ulster Farmers’ and Labourers’ Union and Compulsory Sale Organisation. v. Official launch of the U.I.L. campaign for compulsory purchase. vi. The East Down by-election, 1902. vii. The response to the 1902 land bill. viii. The Land Conference, ix. Conclusion. CHAPTER TWO: INITIAL REACTIONS TO THE 1903 LAND BILL. i. Introduction. ii. The response of the Conservative party. iii. The response of the Liberal opposition to the bill. iv. Nationalist reaction to the bill. v. Unionist reaction to the bill. vi. The attitude of Irish landlords. vii. George Wyndham’s struggle to get the bill to the committee stage. viii. Conclusion. CHAPTER THREE: THE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES THAT FORGED THE WYNDHAM LAND ACT, 1903. i. Introduction. ii. The Estates Commission. iii. The system of price‘zones’. iv. The ‘bonus’ and the financial clauses of Wyndham’s Land Bill. v. Advances to tenant-purchasers. vi. Sale and repurchase of demesnes. vii. The evicted tenants question. viii. The retention of sporting and mineral rights. -

Adverse Possession and the Transmissibility of Possessory Rights – the Dark Side of Land Registration? Mark Pawlowski* *Barris

Adverse Possession and the Transmissibility of Possessory Rights – The Dark Side of Land Registration? Mark Pawlowski* *Barrister, Professor of Property Law, Scholl of Law, University of Greenwich James Brown** **Barrister, Senior Lecturer in Law, Aston University It is trite law that, if unregistered land is adversely possessed for a period of 12 years, the title of the paper owner is automatically barred under s.15 of the Limitation Act 1980. Where the land is registered, however, there is no automatic barring of title by adverse possession1 – instead, after being in adverse possession for a minimum of 10 years,2 the adverse possessor can apply to be registered as the proprietor in place of the registered proprietor of the land.3 Upon receipt of such an application, the Land Registry is obliged to notify various persons interested in the land, including the registered proprietor.4 Those persons then have 65 business days5 within which to object to the registration6 and, in the absence of any objection, the adverse possessor is entitled to be registered as the new proprietor of the land. 7 In these circumstances, the registered proprietor is assumed to have abandoned the land. If, on the other hand, there is an objection, the possessor will not be registered as the proprietor unless he falls within one of the three exceptional grounds listed in paragraph 5, Schedule 6 to the Land Registration Act 2002, where: (1) it would be unconscionable for the registered proprietor to object to the application; (2) the adverse possessor is otherwise entitled to the land; or (3) if the possessor is the owner of adjacent property and has been in adverse possession of the subject land under the mistaken, but reasonable belief, that he is its owner. -

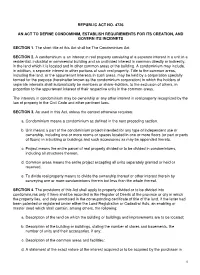

The Condominium Act

REPUBLIC ACT NO. 4726 AN ACT TO DEFINE CONDOMINIM, ESTABLISH REQURIEMENTS FOR ITS CREATION, AND GOVERN ITS INCIDNETS SECTION 1. The short title of this Act shall be The Condominium Act. SECTION 2. A condominium is an interest in real property consisting of a separate interest in a unit in a residential, industrial or commercial building and an undivided interest in common directly or indirectly, in the land which it is located and in other common areas of the building. A condominium may include, in addition, a separate interest in other portions of such real property. Title to the common areas, including the land, or the appurtenant interests in such areas, may be held by a corporation specially formed for the purpose (hereinafter known as the condominium corporation) in which the holders of separate interests shall automatically be members or share−holders, to the exclusion of others, in proportion to the appurtenant interest of their respective units in the common areas. The interests in condominium may be ownership or any other interest in real property recognized by the law of property in the Civil Code and other pertinent laws. SECTION 3. As used in this Act, unless the context otherwise requires: a. Condominium means a condominium as defined in the next preceding section. b. Unit means a part of the condominium project intended for any type of independent use or ownership, including one or more rooms or spaces located in one or more floors (or part or parts of floors) in a building or buildings and such accessories as may be appended thereto. -

Trusts, Equitable Interests and the New Zealand Statute of Frauds

TRUSTS, EQUITABLE INTERESTS AND THE NEW ZEALAND STATUTE OF FRAUDS ROBERT BURGESS* The Property Law Amendment Act 1980 1 contains provisions which effectively patriate sections 7-9 of the Statute of Frauds 1677, replacing the "archaically worded and often obscure provisions"2 of the original English statute with a more modern set of provisions which again have an English derivation being "taken almost word for word"3from that country's Law of Property Act 1925. 4 The new provisions take effect as section 49A of the Property Law Act 1952 and, in so far as they concern the law of trusts, read as follows: 49A(2) A declaration of trust respecting any land or any interest in land shall be manifested and proved by some writing signed by some person who is able to declare such trust or by his will. (3) A disposition of an equitable interest or trust subsisting at the time of the disposition shall be in writing signed by the person disposing of the same or by his agent lawfully authorised in that behalf, or by will. (4) This section does not affect the creation or operation of resulting, implied or constructive trusts. Section 49A is stated5 as being "in substitution for" the corresponding provisions of 1677 and represents a consolidation of those provisions, although perhaps not, as has been suggested, 6 a "true consolidation". The point is that the structure of section 49A would appear to indicate that the ambit of its application is different from that of its predecessor. In particular, the provision contained in section 49A(4) appears to have an application within the context of the section as a whole whereas under * LLB Hons (London), PhD (Edinburgh), Reader in Law, University of East Anglia. -

LAND REGISTRATION for the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY a Conveyancing Revolution

LAND REGISTRATION FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A Conveyancing Revolution LAND REGISTRATION BILL AND COMMENTARY Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 9 July 2001 LAW COMMISSION H M LAND REGISTRY LAW COM NO 271 LONDON: The Stationery Office HC 114 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. THE COMMISSIONERS ARE: The Honourable Mr Justice Carnwath CVO, Chairman Professor Hugh Beale Mr Stuart Bridge· Professor Martin Partington Judge Alan Wilkie QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers Her Majesty’s Land Registry, a separate department of government and now an Executive Agency, maintains the land registers for England and Wales and is responsible for delivering all land registration services under the Land Registration Act 1925. The Chief Land Registrar and Chief Executive is Mr Peter Collis The Solicitor to H M Land Registry is Mr Christopher West The terms of this report were agreed on 31 May 2001. The text of this report is available on the Internet at: http://www.lawcom.gov.uk · Mr Stuart Bridge was appointed Law Commissioner with effect from 2 July 2001. The terms of this report were agreed on 31 May 2001, while Mr Charles Harpum was a Law Commissioner. ii LAW COMMISSION HM LAND REGISTRY LAND REGISTRATION FOR THE TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY A Conveyancing Revolution CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: THE LAND REGISTRATION BILL AND -

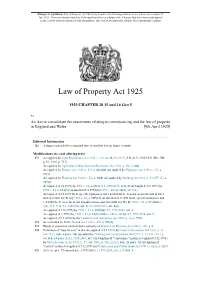

Law of Property Act 1925 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 01 July 2021

Changes to legislation: Law of Property Act 1925 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 01 July 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Law of Property Act 1925 1925 CHAPTER 20 15 and 16 Geo 5 X1 An Act to consolidate the enactments relating to conveyancing and the law of property in England and Wales. [9th April 1925] Editorial Information X1 A dagger appended to a marginal note means that it is no longer accurate Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act applied by Land Registration Act 1925 (c. 21), ss. 36, 38, 69(3), S.R. & O. 1925/1093 (Rev. XII, p. 81: 1925, p. 717) Act applied by Agriculture (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1941 (c. 50), s. 8(4) Act applied by Finance Act 1949 (c. 47), s. 40(4)(b) Act applied by Highways Act 1959 (c. 25), s. 81(3) Act applied by Housing Act 1964 (c. 56), s. 80(5) Act applied by Building Act 1984 (c. 55, SIF 15), s. 107(2) Act applied (1.11.1993) by 1993 c. 28, s. 69(3); S.I. 1993/2134, arts. 25 Act applied (5.1.1994) by 1990 c. 43, s. 81A(8) (as inserted (5.1.1994) by 1993 c. 40, ss. 10(2), 12(1)(2) Act applied (21.9.1995 for E. specified purposes and 1.4.2000 for E. -

Crown Land Legislation Amendment Act 2017

Crown Land Legislation Amendment Act 2017 As at 10 April 2018 See also: Transport Administration Amendment (Sydney Metro) Bill 2018 Note: Amending Acts and amending provisions are subject to automatic repeal pursuant to sec 30C of the Interpretation Act 1987 No 15 once the amendments have taken effect. Long Title An Act to amend certain legislation consequent on the enactment of the Crown Land Management Act 2016. 1 Name of Act This Act is the Crown Land Legislation Amendment Act 2017. 2 Commencement (1) This Act commences on the day on which the Crown Lands Act 1989 is repealed by the Crown Land Management Act 2016, except as provided by this section. (2) Schedule 1 commences on the date of assent to this Act. Schedule 1 (Repealed) Schedule 2 Amendment of legislation referring to reserve trusts 2.1 – Betting and Racing Act 1998 No 114 Section 4 Definitions Omit paragraph (c) of the definition of "approved body" in section 4 (1). Insert instead: (c) a statutory land manager within the meaning of the Crown Land Management Act 2016. 2.2 – Cemeteries and Crematoria Act 2013 No 105 [1] Section 3 Objects of Act Omit "section 11 of the Crown Lands Act 1989 " from section 3 (f). Insert instead "section 1.4 of the Crown Land Management Act 2016 ". [2] Section 4 Interpretation Omit section 4 (3). Insert instead: (3) An expression that is used in this Act and that is defined in the Crown Land Management Act 2016 (not being an expression that is defined in this Act) has the same meaning in this Act in relation to a Crown cemetery or Crown cemetery operator as it has in that Act in relation to dedicated or reserved Crown land or a person responsible for the care, control and management of dedicated or reserved Crown land, respectively. -

An Introduction to Wills and Administration Percy Bordwell

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1929 An Introduction to Wills and Administration Percy Bordwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bordwell, Percy, "An Introduction to Wills and Administration" (1929). Minnesota Law Review. 2068. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2068 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW Journal of the State Bar Association VOLUMIE XIV DECE-MBERP, 1929 No. I AN INTRODUCTION TO WILLS AND ADMINISTRATIONt By PERcy BORDWELL* F REEDOm of testamentary disposition has become second nature to Americans and all others brought up under the influence of Anglo-American law. While the testator cannot take his prop- erty with him nor have rights after he is dead,' yet it is the almost universal rule that by his will he may control the subse- quent course of his property even to the extent of leaving his children penniless.' So extreme a power of testamentary dis- position is probably not to be found elsewhere,' and even in Anglo-American law is, as legal history goes, of comparatively recent date. Up until 1692 it was the law in the northern of the two ecclesiastical provinces into which England is divided that where a testator had wife and children he was entitled to dispose of only one third of his goods and chattels, one third going to the wife and the remaining third to his children.' And such was the custom of London until 1724. -

SJC: Land Registration Not a Factor in Right-Of-Way Dispute Key Ruling Continues Court’S ‘Balanced’ Approach to Easement Law

Established 1872 Reprinted from the issue of March 10th, 2014 www.BankerandTradesman.com T HE R EAL E S T A T E , B ANKING AND C OMME rc IAL W EEKLY FO R M ASSA C HUSE tt S A PUBLICATION OF THE WARREN GROUP PROPERTY LAW SJC: Land Registration Not A Factor In Right-Of-Way Dispute Key Ruling Continues Court’s ‘Balanced’ Approach To Easement Law BY ASHLEY H. BROOKS SPECIAL TO BANKER & TRADESMAN land. dimensions of all easements easement, (b) increase the n a recent major real es- Clifford Martin owns a va- appurtenant to it … are immu- burdens on the owner of the tate law ruling, the Massa- cant lot of registered land table, and Martin has a right of easement in its use and enjoy- Ichusetts Supreme Judicial in an industrial/commercial access over the full width of ment, or (c) frustrate the pur- Court (SJC) extended owners subdivision on the Medford– [the easement].” pose for which the easement of registered land the same Somerville line. The lot has no The SJC disagreed, how- was created.” flexibility frontage on a public way, but ever, and reiterated the Land And even though the dis- that own- is accessible via a right of way Court judge’s finding that pute in Martin v. Simmons ers of un- easement on property owned there is “no principled distinc- Properties involved registered registered by Simmons Properties, which tion between easements on land, the court said: “We dis- land have easement is noted on the cer- registered land and easements cern nothing in the land reg- to defend tificate of registration issued on unrecorded land … ” istration act … to support a easement by the Land Court for Martin’s different understanding of the claims.