Press Making Art out of an Encounter The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Programme As A

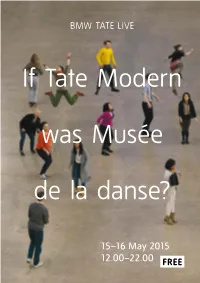

Introduction 15–16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE #dancingmuseum Map Introduction BMW TATE LIVE: If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Tate Modern Friday 15 May and Saturday 16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE Starting with a question – If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Restaurant – this project proposes a fictional transformation of the art museum 6 via the prism of dance. A major new collaboration between Tate Modern and the Musée de la danse in Rennes, France, directed by Members Room dancer and choreographer Boris Charmatz, this temporary 5 occupation, lasting just 48 hours, extends beyond simply inviting the 20 Dancers discipline of dance into the art museum. Instead it considers how the 4 museum can be transformed by dance altogether as one institution 20 Dancers overlaps with another. By entering the public spaces and galleries of 3 Tate Modern, Musée de la danse dramatises questions about how art might be perceived, displayed and shared from a danced and 20 Dancers expo zéro choreographed perspective. Charmatz likens the scenario to trying on 2 a new pair of glasses with lenses that opens up your perception to River Café forms of found choreography happening everywhere. Entrance 1 Shop Shop Turbine Hall Presentations of Charmatz’s work are interwoven with dance À bras-le-corps 0 to manger 0performances that directly involve viewers. Musée de la danse’s Main regular workshop format, Adrénaline – a dance floor that is open Entrance to everyone – is staged as a temporary nightclub. The Turbine Hall oscillates between dance lesson and performance, set-up and take-down, participation and party. -

Danh Vō Bà Rja, Vietnam, 1975 Lives and Works in Berlin, Germany

kurimanzutto danh vō Bà Rja, Vietnam, 1975 lives and works in Berlin, Germany education & residencies 2013 Villa Medici Artist Residency, Rome. 2009 Kadist Art Foundation Residency, Paris. 2006 Villa Aurora Artist Residency, Los Angeles. 2002–2004 Städelschule, Frankfurt. 2000–2001 Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen. grants & awards 2015 Arken Art Prize, Denmark. 2012 Hugo Boss Prize awarded by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, United States. 2009 Nominee for the Nationalgalerie Prize for Young Art, Germany. 2007 BlauOrange Kunstpreis der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken, Germany. solo exhibitions 2020 Danh Vo. Wising Art Place Atelier, Taipei, Taiwan. Danh Vo oV hnaD. The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan. Danh Vo Presents. The Nivaagaard Collection, Denmark. Chicxulub. White Cube Bermondsey, London. 2019 The Mudam Collection and Pinault Collection in dialogue. Mudam, Luxemburg. Dahn Vo: Untitled. South London Gallery. kurimanzutto To Each his Due. Take Ninagawa, Tokyo. We The People. Media Gallery, New York. Danh Vo. kurimanzutto, Mexico. Danh Vo. Cathedral Block Prayer Stage Gun Stock. Marian Goodman, London. 2018 Garden with Pigeons at Flight. Estancia FEMSA – Casa Luis Barragán, Mexico City. Take My Breath Away. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Noguchi for Danh Vo: counterpoint. M+ Pavilion, West Kowloon, Hong Kong. Take My Breath Away, SMK, Copenhagen. Danh Vo. Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, France. 2017 Ng Teng Fong Roof Garden Commission, National Gallery, Singapore. 2016 We the People. Aspen Art Museum, United States. Ng Teng Fong Roof Garden Commission: Danh Vo. National Gallery Singapore. Danh Vo. White Cube, Hong Kong. 2015 Destierra a los sin rostro / Premia tu gracia (Banish the Faceless / Reward your Grace). -

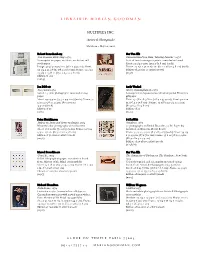

L I B R a I R I E M a R I a N G O O D M

L I B R A I R I E M A R I A N G O O D M A N MULTIPLES INC. Artists & Photographs March 20 – May 22, 2021 Robert Rauschenberg Ger Van Elk Two Reasons Birds Sing, 1979, Conversation Piece from "Missing Persons", 1976 Screenprint on paper, on fabric, on Arches roll A set of two chromogenic prints, mounted on board stock paper Sheet: 23 1/4 x 33 in. (59.1 x 83.8 cm) (each); Image: 30 3/4 x 19 1/2 in. (78.1 x 49.5 cm); Sheet: Frame: 24 1/2 x 31 x 1 1/2 in. (62.2 x 78.7 x 3.8 cm) (each) 30 3/4 x 23 1/8 in. (78.1 x 58.7 cm); Frame: 33 1/2 x Edition of 45 plus 10 artist's proofs 25 3/4 x 1 7/8 in. (85.1 x 65.4 x 4.8 cm) (0158) Edition of 100 (2069) Jan Dibbets Andy Warhol Sea / Land, 1974 Merce Cunningham II, 1979 Set of 2; 5 color photographs, mounted on rag Screenprint on Japanese deacidified imported Florentine paper gift paper Sheet: 29 x 39 in. (73.7 x 99.1 cm) (each); Frame: 31 Plate: 27 1/8 x 18 7/8 in. (68.9 x 47.9 cm); Sheet: 30 x 20 1/2 x 41 5/8 x 1 3/4 in. (80 x 105.7 x in. (76.2 x 50.8 cm) ; Frame: 32 5/8 x 22 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. -

Press Dan Graham: Whitney Museum of American Art Artforum, October

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Dan Graham: WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART By Hal Foster (October 2009) OF ACTIVE ARTISTS over the age of sixty in the United States, Dan Graham may be the most admired figure among younger practitioners. Though never as famous as his peers Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, and Bruce Nauman, Graham has now gained, as artist-critic John Miller puts it, a “retrospective public.” Why might this be so? “Dan Graham: Beyond,” the excellent survey curated by Bennett Simpson of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (the show’s inaugural venue), and Chrissie Iles of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, offers ample reasons. If Minimalism was a crux in postwar art, a final closing of the modernist paradigm of autonomous painting and a definitive opening of practices involving actual bodies in social spaces, its potential still had to be activated, and with his colleagues Graham did just that. (This moment is nicely narrated by Rhea Anastas in the catalogue for the show.) “All my work is a critique of Minimal art,” Graham states (in an intriguing interview with artist Rodney Graham also in the catalogue); “it begins with Minimal art, but it’s about spectators observing themselves as they’re observed by other people.” Hence many of the forms associated with his work: interactions between two performers; performances by the artist that directly engage audiences; films and videos reflexive about the space of their making; installations involving viewers in partitions, mirrors, and/or videos; architectural models; and pavilions of translucent and reflective glass. -

Powered by Julie Mehretu Lot 1

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS Manal Abu-Shaheen Andrea Galvani Yoko Ono Golnar Adili Ethan Greenbaum Kenneth Pietrobono Elia Alba Camille Henrot Claudia Peña Salinas Hope Atherton Brigitte Lacombe Leah Raintree Firelei Báez Anthony Iacono Gabriel Rico Leah Beeferman Basim Magdy Paul Mpagi Sepuya Agathe de Bailliencourt Shantell Martin Arlene Shechet Ali Banisadr Takesada Matsutani Rudy Shepherd Mona Chalabi Josephine Meckseper Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir/Shoplifter Kevin Cooley Julie Mehretu Elisabeth Smolarz William Cordova Sarah Michelson Sarah Cameron Sunde N. Dash Richard Mosse Michael Wang Sandra Erbacher Vik Muniz Meg Webster Liana Finck Rashaad Newsome Tim Wilson AUCTION COMMITTEE Waris Ahluwalia, Designer and Actor Anthony Allen, Director, Paula Cooper Gabriel Calatrava, Founder, CAL Andrea Cashman, Director, David Zwirner Brendan Fernandes, Artist Michelle Grey, Executive Creative and Brand Director, Absolut Art Prabal Gurung, Designer, Founder and Activist Peggy Leboeuf, Director, Galerie Perrotin Michael Macaulay, SVP, Sotheby's Yoko Ono, Artist Bettina Prentice, Founder and Creative Director, Prentice Cultural Communications Olivier Renaud-Clément Olympia Scarry, Artist and Curator Andrea Schwan, Andrea Schwan Inc. Brent Sikkema, Founder and Owner, Sikkema Jenkins & Co Powered by Julie Mehretu Lot 1 Mind-Wind Fusion Drawings #5 2019 Ink and acrylic on paper 26 x 40 in (66 x 101.6 cm) Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York Estimated value: $80,000 Mehretu’s work is informed by a multitude of sources including politics, literature and music. Most recently her paintings have incorporated photographic images from broadcast media which depict conflict, injustice, and social unrest. These graphic images act as intellectual and compositional points of departure; ultimately occluded on the canvas, they remain as a phantom presence in the highly abstracted gestural completed works. -

Exhibiting Performance Art's History

EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART’S HISTORY Harry Weil 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov 2009), a group show at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York, November 1, 2009 –May 3, 2010 and Off the Wall: Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions, a group show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, July 1–September 19, 2010. he past decade has born witness 100 Years, curated by MoMA PS1 cura- to the proliferation of perfor- tor Klaus Biesenbach and art historian mance art in the broadest venues RoseLee Goldberg, structured a strictly Tyet seen, with notable retrospectives of linear history of performance art. A Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, Allan five-inch thick straight blue line ran the Kaprow, and Tino Sehgal held in Europe length of the exhibition, intermittently and North America. Performance has pierced by dates written in large block garnered a space within the museum’s letters. The blue path mimics the simple hallowed halls, as these institutions have red and black lines of Alfred Barr’s chart hurriedly begun collecting performance’s on the development of modern art. Barr, artifacts and documentation. As such, former director of MoMA, created a museums play an integral role in chroni- simple scientific chart for the exhibition cling performance art’s little-detailed Cubism and Abstract Art (1935) that history. 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov streamlines the genealogy of modern 2009) at MoMA PS1 and Off the Wall: art with no explanatory text, reduc- Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions at ing it to a chronological succession of the Whitney Museum of American avant-garde movements. -

Ari Benjamin Meyers

ARI BENJAMIN MEYERS Born 1972 (New York, USA) Lives and works in Berlin, Germany EDUCATION 1996–1998 Fullbright Grant: Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler, Berlin, Germany, Certificate in Conducting 1994–1996 The Peabody Institue, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, MM Conducting 1990–1994 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, BA Composition (Cum Laude) 1990–1997 The Juilliard School Pre-College Division, New York, New York, USA, Composition and Piano SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2019 In Concert, OGR – Officine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2018 Kunsthalle for Music, Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands 2017 An exposition, not an exhibition, Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, China Solo for Ayumi, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany 2016 The Name Of This Band is The Art, RaebervonStenglin, Zurich, Switzerland 2015 Atlas of Melodies, abc Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2013 Black Thoughts, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany Songbook, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Musikwerke Bildene Künstler, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Germany Oscillations, Trafo Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland 2015 music, Fahrbereitschaft – Haubrok Collection, Berlin, Germany Artists’ Weekend, Ngorongoro, Berlin, Germany The Verismo Project, Kunst im Kino, Kino International, Berlin, Germany 2014 Supergroup, Tanzhaus NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany I Take Part and the Part Takes Me, Gallery Tanja Wagner, Berlin, Germany The New Empirical, Hatje Cantz & Du Moulin im Bikini, Berlin, Germany 2012 I Wish This Was a Song. Music in Contemporary Art, -

FRED SANDBACK Born 1943 in Bronxville, New York

This document was updated on April 27, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. FRED SANDBACK Born 1943 in Bronxville, New York. Died 2003 in New York, New York. EDUCATION 1957–61 Williston Academy, Easthampton, Massachusetts 1961–62 Theodor-Heuss-Gymnasium, Heilbronn 1962–66 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, BA 1966–69 Yale School of Art and Architecture, New Haven, Connecticut, MFA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1968 Fred Sandback: Plastische Konstruktionen. Konrad Fischer Galerie, Düsseldorf. May 18–June 11, 1968 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. October 24–November 17, 1968 1969 Fred Sandback: Five Situations; Eight Separate Pieces. Dwan Gallery, New York. January 4–January 29, 1969 Fred Sandback. Ace Gallery, Los Angeles. February 13–28, 1969 Fred Sandback: Installations. Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld. July 5–August 24, 1969 [catalogue] 1970 Fred Sandback. Dwan Gallery, New York. April 4–30, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galleria Françoise Lambert, Milan. Opened November 5, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. Opened November 13, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. 1970 1971 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. January 27–February 13, 1971 Fred Sandback. Galerie Reckermann, Cologne. March 12–April 15, 1971 Fred Sandback: Installations; Zeichnungen. Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zurich. November 4–December 8, 1971 1972 Fred Sandback. Galerie Diogenes, Berlin. December 2, 1972–January 27, 1973 Fred Sandback. John Weber Gallery, New York. December 9, 1972–January 3, 1973 Fred Sandback. Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zürich. Opened December 19, 1972 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. 1972 Fred Sandback: Neue Arbeiten. Galerie Reckermann, Cologne. -

Steve Mcqueen

Steve McQueen Born in London, England, 1969 Lives and works in London, England, and Amsterdam, Netherlands Education Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, New York NY, 1994 Goldsmith's College, London, England, 1993 Chelsea School of Art, London, England, 1990 Solo Exhibitions 2022 Forthcoming: Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, Italy 2021 Forthcoming: Ashes, Turner Contemporary, Margate, England 2020 Steve McQueen, Tate Modern, London, England 2019 Year 3, Tate Britain, London, England 2018 Gravesend, Groundwork by CAST, Helston, Cornwall, England 2017 Steve McQueen: End Credits, Perez Art Museum Miami, Miami FL Steve McQueen: Ashes, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, England Remember Me, Een Werk, Amsterdam, Netherlands Steve McQueen: End Credits, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago IL Inbox: Steve McQueen, Museum of Modern Art, New York NY Steve McQueen: Ashes, Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, Boston MA 2016 Open Plan: Steve McQueen, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY Steve McQueen, Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris, France 2014 Steve McQueen: Ashes, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England Drumroll, MOCA Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles CA Steve McQueen, Espace Louis Vuitton, Tokyo, Japan 2013 Steve McQueen: Works, Schaulager, Basel, Switzerland Steve McQueen: Rayners Lane, xavierlaboulbenne, Berlin, Germany 2012 Blues Before Sunrise, Site-specific installation, Temporary Stedelijk 3, Vondelpark, Amsterdam, Netherlands Steve McQueen: Works, Art Institute of Chicago, Regenstein Hall, Chicago IL 2010 Steve McQueen, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York NY 2009 Steve McQueen. Giardini, British Pavilion, Biennale di Venezia 53, Venice, Italy Steve McQueen. Gravesend/Unexploded, De Pont Museum of Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands Steve McQueen. Girls, Tricky, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago IL Steve McQueen. -

Marian Goodman Gallery

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY TINO SEHGAL Born: London, England, 1976 Lives and works in Berlin Awards: Golden Lion, Venice Biennale, 2013 Shortlist for the Turner Prize, 2013 American International Association of Art Critics: Best Show Involving Digital Media, Video, Film Or Performance, 2011 SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Enoura Observatory, Odawara Art Foundation, Japan Accelerator Stockholms University, Stockholm, Sweden Tino Sehgal, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York 2018 Tino Sehgal, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Germany This Success, This Failure, Kunsten, Aalborg, Denmark This You, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., USA Oficine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2017 Tino Sehgal, Fondation Beyeler, Switzerland V-A-C Live: Tino Sehgal, the New Tretyakov Gallery and the Schusev State Museum of Architecture, Moscow Russia 2016 Carte Blanche to Tino Sehgal, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France Jemaa el-Fna, Marrakesh, Morocco Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Lichthof, Germany Sehgal / Peck / Pite / Forsythe, Opéra de Paris, Palais Garnier, France 2015 A Year at the Stedelijk: Tino Sehgal, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tino Sehgal, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany Tino Sehgal, Helsinki Festival, Finland 2014 This is so contemporary, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney These Associations, CCBB, Centro Cultural Banco de Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil These Associations, Pinacoteca do Estado de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil 2013 Tino Sehgal, Musee d'Art Contemporain de Montreal, Montreal, Canada Tino Sehgal: This Situation, -

Tino Sehgal's

KALDOR PUBLIC ART PROJECT 29: TINO SEHGAL’S THIS IS SO CONTEMPORARY For the 29th Kaldor Public Art Project, internationally acclaimed artist Tino Sehgal presents This is so contemporary, from 6 – 23 February 2014 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Kaldor Public Art Projects and the Art Gallery of New South Wales have a long-standing relationship, which began with Project 3: Gilbert and George in 1973. This is so contemporary, the third project Kaldor Public Art Projects has presented in the Gallery’s classical vestibule, is spontaneous and contagiously uplifting, directly engaging the Gallery’s visitors. Sehgal has pioneered a radical and captivating way of making art. He orchestrates interpersonal encounters through dance, voice and movement, which have become renowned for their intimacy. This is so contemporary, first presented at the 2005 Venice Biennale and making its Australian debut, is no exception. In 2013, Sehgal was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, one of the world’s most prestigious art awards, and was shortlisted for the Tate Modern’s Turner Prize. Key recent exhibitions include This Progress at the Guggenheim New York in 2010, These Associations at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2012 and This Variation at dOCUMENTA 13. Sehgal leaves no material traces, creating something that is at once valuable and entirely immaterial in a world already full of objects. His works reside only in the space and time they occupy, and in the memory of the work and its reception. In order to focus all the attention on the physical evidence, the artist does not allow his work to be photographed or illustrated - no documentation or reproduction is permitted. -

PROJECT 27 13 Rooms 2013 13 Rooms 11 – 21 April 2013 Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney

PROJECT 27 13 Rooms 2013 13 Rooms 11 – 21 April 2013 Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney BIOGRAPHIES HANS ULRICH OBRIST Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist is Co-director of Exhibitions and Programs and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London. He has previously served as curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Museum in Progress, Vienna. KLAUS BIESENBACH Klaus Biesenbach is Director of MoMA PS1 in New York and a Chief Curator at Large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He was the Founding Director of both the Kunst- Werke Institute of Contemporary Art in Berlin and the Berlin Biennale. Key international exhibitions organised by Biesenbach include MoMA’s landmark show Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present (2010) and Hybrid Workspace at documenta X (Kassel, 1997 ). EXHIBITING ARTISTS Marina Abramović; John Baldessari; Joan Jonas; Damien Hirst; Tino Sehgal; Allora and Calzadilla; Simon Fujiwara; Xavier Le Roy; Laura Lima; Roman Ondak; Santiago Sierra; Xu Zhen; Clark Beaumont FACTS It’s not called 13 Performances because it’s not 13 performances. It’s not called 13 Artists because that would be irritating. It’s not called 13 Sculptures because that would be misleading. Instead it’s called 13 Rooms. – Klaus Biesenbach Exhibitions are fundamentally a medium of social encounter. – Hans Ulrich Obrist 13 Rooms ran for 11 days at Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney. The exhibition was originally commissioned as 11 Rooms by Manchester International Festival, the International Arts Festival RUHRTRIENNALE 2012- 2014 and Manchester Art Gallery. In addition to the 12 international artists selected to participate in the project, Australian artist duo Clark Beaumont were invited by the curators to present work in a new thirteenth room.