Robert French, 'Executive Power in Australia' [FINAL VERSION]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting the Constitution — Words, History and Changev

INTERPRETING THE CONSTITUTION — WORDS, HISTORY AND CHANGE* THE HON CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERT FRENCH AC** The Constitution defi nes the essential architecture of our legal universe. Within that framework Parliament makes its laws. Under the authority conferred by the Constitution and by Parliament, the executive makes its regulations and instruments and administers the laws made by the Parliament. Within that framework the courts hear and determine cases including cases about the interpretation of the Constitution and of laws made under it and the extent of legislative and executive powers fl owing from them. Ubiquitous in that universe is the common law, which, as Sir Owen Dixon observed, supplies principles in aid of the interpretation of the Constitution.1 He was not averse to cosmological metaphor. He said of the common law that: ‘[it] is more real and certainly less rigid than the ether with which scientists were accustomed to fi ll interstellar space. But it serves all, and more than all, the purposes in surrounding and pervading the Australian system for which, in the cosmic system, that speculative medium was devised’.2 An updated metaphor for the common law today in lieu of ‘ether’ might be ‘dark energy’. Our metaphorical constitutional universe is not to be likened to the 19th century Newtonian model of the real universe. That is to say, it is not driven by precise laws with determined meanings and a single predictable outcome for each of their applications. Over the last century our view of the real universe has been radically altered, not least by quantum theory which builds uncertainty into the fabric of physical reality. -

The Section 92 Revolution

Encounters with Constitutional Interpretation and Legal Education (2018) James Stellios (ed) Chapter 1 The Section 92 Revolution The Hon Stephen Gageler Nothing could be more disappointing to a legal scholar than to labour over the produc- tion of a treatise on an area of law only to see that treatise almost immediately rendered redundant by a revolutionary decision of an ultimate court. Equally and oppositely, nothing could be more satisfying to a young, ambitious and energetic legal scholar than to take part in the litigation which produces a revolutionary decision of an ultimate court on a topic squarely within his or her field of expertise. Michael Coper experienced the disappointment and the satisfaction. As a junior academic at the University of New South Wales, he turned his doctoral thesis entitled The Judicial Interpretation of Section 92 of the Australian Constitution into a 400-page book, which he published in 1983 as Freedom of Interstate Trade under the Australian Constitution. Just four years later, he accepted a brief to appear with Ron Sackville as junior counsel to the Solicitor-General for New South Wales, Keith Mason QC, on behalf of the Attorney-General for New South Wales intervening in the hearing before the High Court of Cole v Whitfield.1 When Cole v Whitfield was decided in 1988, his academic thesis was largely vindicated, the complexities of the case law which he had sought to tease apart and critique were largely swept away. As the result of the publication of that single judgment, his detailed, insightful and colourfully written book was destined immediately to be remaindered. -

Williams V Commonwealth: Commonwealth Executive Power

CASE NOTE WILLIAMS v COMMONWEALTH* COMMONWEALTH EXECUTIVE POWER AND AUSTRALIAN FEDERALISM SHIPRA CHORDIA, ** ANDREW LYNCH† AND GEORGE WILLIAMS‡ A majority of the High Court in Williams v Commonwealth held that the Common- wealth executive does not have a general power to enter into contracts and spend public money absent statutory authority or some other recognised source of power. This article surveys the Court’s reasoning in reaching this surprising conclusion. It also considers the wider implications of the case for federalism in Australia. In particular, it examines: (1) the potential use of s 96 grants to deliver programs that have in the past been directly funded by Commonwealth executive contracts; and (2) the question of whether statutory authority may be required for the Commonwealth executive to participate in inter- governmental agreements. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 190 II Background ............................................................................................................... 191 III Preliminary Issues .................................................................................................... 194 A Standing ........................................................................................................ 194 B Section 116 ................................................................................................... 196 C Validity of Appropriation .......................................................................... -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Curriculum Vitae of the Honourable Chief Justice Robert French AC 1

Annex Curriculum Vitae of The Honourable Chief Justice Robert French AC 1. Personal Background Robert Shenton French is a citizen of Australia, born in Perth, Western Australia on March 19, 1947. He married Valerie French in 1976. They have three sons and two granddaughters. 2. Education Chief Justice French was educated at St Louis Jesuit College, Claremont in Western Australia and then at the University of Western Australia from which he graduated in 1967 with a Bachelor of Science degree majoring in physics and in 1970 with a Bachelor of Laws. He undertook two years of articles of clerkship with a law firm in Perth. 3. Professional History Chief Justice French was admitted to practice in Western Australia in December 1972 as a Barrister and Solicitor – the profession in Western Australia being a fused profession. In 1975, with three friends, he established a law firm in which he practised as both Barrister and Solicitor until 1983 when he commenced practice at the Independent Bar in Western Australia. While in practice he served as a part-time Member of the Western Australian Law Reform Commission, the Western Australian Legal Aid Commission, the Trade Practices Commission (now known as the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) and as Deputy President and later President of the Town Planning Appeal Tribunal of Western Australia. On November 25, 1986, Chief Justice French was appointed as a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. He continued to serve as a Judge of that Court until September 1, 2008. As a Judge of that Court he sat in both its original and appellate jurisdiction dealing with a wide range of civil cases including commercial disputes, corporations, intellectual property, bankruptcy and corporate insolvency, taxation, competition law, industrial law, constitutional law and public administrative law. -

Speech Delivered at the 10Th Anniversary Conference of the Asia-Pacific Regional Arbitration Group, Sofitel, Melbourne, 27 March 2014)

Australia’s Place in the World Remarks of the Honourable Marilyn Warren AC Chief Justice of Victoria to the Law Society of Western Australia Law Summer School 2017, Perth, Western Australia Friday 17 February 2017* Introduction First things first, what is the world in which Australia is placed? The rate of change seen particularly in 2016 with BREXIT and the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency of the United States is astonishing and must have far ranging and reaching consequences beyond the short term. The changes taking place abroad will have an undeniable impact at home. ‘Australia’s place in the world’ was a prescient yet challenging choice of topic by the organisers of this conference as it asks us to draw up a map while the ground is shifting beneath our feet. Page 1 of 48 * The author acknowledges the invaluable assistance of her Research Assistant David O’Loughlin. Supreme Court of Victoria 17 February 2017 Overview Perth is a fitting location to discuss Australia’s place in the world. At the Asia-Pacific Regional Arbitration Group conference some years ago, Chief Justice Martin noted that Perth is closer to Singapore than it is to Sydney, and that it enjoys the same time zone as many Asian commercial centres. He said that to appreciate Western Australia’s orientation to Asia, he need only speak to his neighbours.1 With our location in mind, today I would like set the scene by looking at the shift from the old world to the new. I will look at some recent developments in global politics and trade, including President Trump’s inauguration, Prime Minister May’s Brexit plans, and China’s increasing engagement with the global economy. -

Hybrid Constitutional Courts: Foreign Judges on National Constitutional Courts

Hybrid Constitutional Courts: Foreign Judges on National Constitutional Courts ROSALIND DIXON* & VICKI JACKSON** Foreign judges play an important role in deciding constitutional cases in the appellate courts of a range of countries. Comparative constitutional scholars, however, have to date paid limited attention to the phenomenon of “hybrid” constitutional courts staffed by a mix of local and foreign judges. This Article ad- dresses this gap in comparative constitutional schol- arship by providing a general framework for under- standing the potential advantages and disadvantages of hybrid models of constitutional justice, as well as the factors likely to inform the trade-off between these competing factors. Building on prior work by the au- thors on “outsider” models of constitutional interpre- tation, it suggests that the hybrid constitutional mod- el’s attractiveness may depend on answers to the following questions: Why are foreign judges appoint- ed to constitutional courts—for what historical and functional reasons? What degree of local democratic support exists for their appointment? Who are the foreign judges, where are they from, what are their backgrounds, and what personal characteristics of wisdom and prudence do they possess? By what means are they appointed and paid, and how are their terms in office structured? How do the foreign judges approach their adjudicatory role? When do foreign * Professor of Law, UNSW Sydney. ** Thurgood Marshall Professor of Constitutional Law, Harvard Law School. The authors thank Anna Dziedzic, Mark Graber, Bert Huang, David Feldman, Heinz Klug, Andrew Li, Joseph Marko, Sir Anthony Mason, Will Partlett, Iddo Porat, Theunis Roux, Amelia Simpson, Scott Stephenson, Adrienne Stone, Mark Tushnet, and Simon Young for extremely helpful comments on prior versions of the paper, and Libby Bova, Alisha Jarwala, Amelia Loughland, Brigid McManus, Lachlan Peake, Andrew Roberts, and Melissa Vogt for outstanding research assistance. -

What Is Executive Power?

1 What is Executive Power? I Introduction In the 1988 case of Davis v Commonwealth, Mason J said of executive power that it is potentially very broad yet ‘its scope [is not] amenable to exhaustive definition.’1 Executive power is a power with significant content but ill-defined limits. It is not the particular power of lawmaking, or of determining disputes but, rather, the general power to carry out all the other functions of government. In the Westminster tradition, all governmental power derived originally from the Crown2 and independent legislative3 and judicial4 functions were a subsequent development. The Coronation Charter of Henry I, the immediate successor to William I and, therefore, the first postconquest king to have a coronation as such, illustrates the breadth of the original power of the Crown (the following excerpts indicating executive, judicial and legislative power respectively): 1 Davis v Commonwealth (1988) 166 CLR 79, 93. 2 Magna Carta 1215 (Imp); NSW v Commonwealth (1975) 135 CLR 337, 480, 487–91 (‘Seas and Submerged Lands Case’) (Jacobs J); J H Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, (Butterworths, 2nd ed, 1979) 12–15; John Gillingham, ‘The Early Middle Ages 1066–1290’ in Kenneth Morgan (ed), The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain (Oxford University Press, 1984), 104; Elizabeth Wicks, The Evolution of a Constitution: Eight Key Moments in British Constitutional History(Hart, 2006) 3–6; cf Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106, 137–8 Mason CJ discussing ‘sovereign power which resides in the people’ by virtue of the mechanism for constitutional amendment being a referendum under s 128 of the Constitution. -

The Toohey Legacy: Rights and Freedoms, Compassion and Honour

57 THE TOOHEY LEGACY: RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS, COMPASSION AND HONOUR GREG MCINTYRE* I INTRODUCTION John Toohey is a person whom I have admired as a model of how to behave as a lawyer, since my first years in practice. A fundamental theme of John Toohey’s approach to life and the law, which shines through, is that he remained keenly aware of the fact that there are groups and individuals within our society who are vulnerable to the exercise of power and that the law has a role in ensuring that they are not disadvantaged by its exercise. A group who clearly fit within that category, and upon whom a lot of John’s work focussed, were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In 1987, in a speech to the Student Law Reform Society of Western Australia Toohey said: Complex though it may be, the relation between Aborigines and the law is an important issue and one that will remain with us;1 and in Western Australia v Commonwealth (Native Title Act Case)2 he reaffirmed what was said in the Tasmanian Dam Case,3 that ‘[t]he relationship between the Aboriginal people and the lands which they occupy lies at the heart of traditional Aboriginal culture and traditional Aboriginal life’. A University of Western Australia John Toohey had a long-standing relationship with the University of Western Australia, having graduated in 1950 in Law and in 1956 in Arts and winning the F E Parsons (outstanding graduate) and HCF Keall (best fourth year student) prizes. He was a Senior Lecturer at the Law School from 1957 to 1958, and a Visiting Lecturer from 1958 to 1965. -

Speech by the Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma at the Networking Dinner Hosted by Tokyo ETO Seoul, Korea 23 September 2019

Speech by The Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma at the Networking Dinner hosted by Tokyo ETO Seoul, Korea 23 September 2019 The Rule of Law, the Common Law and Business: a Hong Kong Perspective 1. With the recent troubling events in Hong Kong, the focus has been on the rule of law. This concept is as important here in Korea as it is in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is a part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). On 1 July 1997, the PRC resumed the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong. The constitutional position of Hong Kong is contained in a constitutional document called the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. 1 It is significant in at least the following two respects: first, it states the principles reflecting the implementation of the PRC’s basic policies towards Hong 1 Promulgated and adopted by the National People’s Congress under the Constitution of the PRC. - 2 - Kong2 – the main one being the policy of “One Country Two Systems”; and secondly, for the first time in Hong Kong’s history, fundamental rights are expressly set out. These fundamental rights include the freedom of speech, the freedom of conscience, access to justice etc. 2. The theme of the Basic Law was one of continuity, meaning that one of its primary objectives was the continuation of those institutions and features that had served Hong Kong well in the past and that would carry on contributing to Hong Kong’s success in the future. -

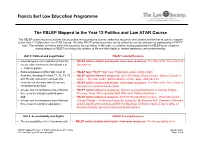

2020JAN Yr 12 PAL ATAR Course Mapped to the FBLEP.Docx

Francis Burt Law Education Programme The FBLEP Mapped to the Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course The FBLEP online resources include classroom/pre and post-visit resources, reference resources and student and teacher resources mapped to the Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course. All of the FBLEP online resources can be utilised by schools that are not participating in FBLEP visits. The activities and tasks within the resources are not reliant, in the main, on students having participated in FBLEP tours. However, participating in a FBLEP tour brings the syllabus to life and adds depth to student awareness and understanding. Unit 3: Political and Legal Power FBLEP Activity/Resource • Lawmaking process in parliament and the • FBLEP online student and teacher classroom resources: The Role of the Three Arms of courts, with reference to the influence of Government • Political parties • Roles and powers of the High Court of • FBLEP tour: FBLEP High Court Programme (when sitting in WA) Australia, including Sections 71, 72, 73, 75 • FBLEP online reference resources: 2010 Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture: ‘Being a Chapter 3 and 76 with reference to at least one Judge’ – The Hon. Justice Michael Barker, Lecture paper and Video file common law decision and at least one • FBLEP online student and teacher classroom resources: The Role of the Three Arms of constitutional decision Government (constitutional decision) • at least one contemporary issue (the last • FBLEP online reference resources: Non-Consensual Distribution of Intimate Images three years) relating -

1 Indigenous Recognition Or Is It a Doomed Mission?

Indigenous recognition or is it a doomed mission? Proposals to Constitutionally recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their language are often divided into the symbolic as either amending the preamble or standalone provision(s) which acknowledge Indigenous identity and the more substantive such as a constitutional ban on racial discrimination or a First Nation’s voice to Parliament. While all Australian States have now adopted purely symbolic Indigenous recognition provisions, it has generally fallen out of favour at the national level. Are there any good reasons to adopt purely symbolic forms of Constitutional recognition? One should compare the experience of reforms in the Australian States. I Necessity and broader movements The present state of non-recognition of indigenous culture and language in the national Constitution can inflict harm and act as a form of oppression, As Taylor states, this can imprison individuals and groups in a false, distorted and reduced mode of being.1 Australian First Nation Peoples (FNP) as a minority group experience marginalisation from mainstream social, political and economic discourse.2 A preamble or standalone provision(s) recognising indigenous culture and language may assist in changing societal and legislative measures in favour of substantive equality. With the intended function of redeeming the document, unifying communities and reducing or eliminating barriers to entry in the otherwise marginalized activities. The proposal has national approval in principle by all major political parties, with intentions of furthering national reconciliation and to guard Australia’s reputation internationally through indigenous wellbeing.3 Instilling in the Constitution a restorative justice theory, whereby in the interests of equality indigenous are treated differently4 by their positive inclusion.