Interpreting the Constitution — Words, History and Changev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae of the Honourable Chief Justice Robert French AC 1

Annex Curriculum Vitae of The Honourable Chief Justice Robert French AC 1. Personal Background Robert Shenton French is a citizen of Australia, born in Perth, Western Australia on March 19, 1947. He married Valerie French in 1976. They have three sons and two granddaughters. 2. Education Chief Justice French was educated at St Louis Jesuit College, Claremont in Western Australia and then at the University of Western Australia from which he graduated in 1967 with a Bachelor of Science degree majoring in physics and in 1970 with a Bachelor of Laws. He undertook two years of articles of clerkship with a law firm in Perth. 3. Professional History Chief Justice French was admitted to practice in Western Australia in December 1972 as a Barrister and Solicitor – the profession in Western Australia being a fused profession. In 1975, with three friends, he established a law firm in which he practised as both Barrister and Solicitor until 1983 when he commenced practice at the Independent Bar in Western Australia. While in practice he served as a part-time Member of the Western Australian Law Reform Commission, the Western Australian Legal Aid Commission, the Trade Practices Commission (now known as the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) and as Deputy President and later President of the Town Planning Appeal Tribunal of Western Australia. On November 25, 1986, Chief Justice French was appointed as a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. He continued to serve as a Judge of that Court until September 1, 2008. As a Judge of that Court he sat in both its original and appellate jurisdiction dealing with a wide range of civil cases including commercial disputes, corporations, intellectual property, bankruptcy and corporate insolvency, taxation, competition law, industrial law, constitutional law and public administrative law. -

Speech Delivered at the 10Th Anniversary Conference of the Asia-Pacific Regional Arbitration Group, Sofitel, Melbourne, 27 March 2014)

Australia’s Place in the World Remarks of the Honourable Marilyn Warren AC Chief Justice of Victoria to the Law Society of Western Australia Law Summer School 2017, Perth, Western Australia Friday 17 February 2017* Introduction First things first, what is the world in which Australia is placed? The rate of change seen particularly in 2016 with BREXIT and the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency of the United States is astonishing and must have far ranging and reaching consequences beyond the short term. The changes taking place abroad will have an undeniable impact at home. ‘Australia’s place in the world’ was a prescient yet challenging choice of topic by the organisers of this conference as it asks us to draw up a map while the ground is shifting beneath our feet. Page 1 of 48 * The author acknowledges the invaluable assistance of her Research Assistant David O’Loughlin. Supreme Court of Victoria 17 February 2017 Overview Perth is a fitting location to discuss Australia’s place in the world. At the Asia-Pacific Regional Arbitration Group conference some years ago, Chief Justice Martin noted that Perth is closer to Singapore than it is to Sydney, and that it enjoys the same time zone as many Asian commercial centres. He said that to appreciate Western Australia’s orientation to Asia, he need only speak to his neighbours.1 With our location in mind, today I would like set the scene by looking at the shift from the old world to the new. I will look at some recent developments in global politics and trade, including President Trump’s inauguration, Prime Minister May’s Brexit plans, and China’s increasing engagement with the global economy. -

Hybrid Constitutional Courts: Foreign Judges on National Constitutional Courts

Hybrid Constitutional Courts: Foreign Judges on National Constitutional Courts ROSALIND DIXON* & VICKI JACKSON** Foreign judges play an important role in deciding constitutional cases in the appellate courts of a range of countries. Comparative constitutional scholars, however, have to date paid limited attention to the phenomenon of “hybrid” constitutional courts staffed by a mix of local and foreign judges. This Article ad- dresses this gap in comparative constitutional schol- arship by providing a general framework for under- standing the potential advantages and disadvantages of hybrid models of constitutional justice, as well as the factors likely to inform the trade-off between these competing factors. Building on prior work by the au- thors on “outsider” models of constitutional interpre- tation, it suggests that the hybrid constitutional mod- el’s attractiveness may depend on answers to the following questions: Why are foreign judges appoint- ed to constitutional courts—for what historical and functional reasons? What degree of local democratic support exists for their appointment? Who are the foreign judges, where are they from, what are their backgrounds, and what personal characteristics of wisdom and prudence do they possess? By what means are they appointed and paid, and how are their terms in office structured? How do the foreign judges approach their adjudicatory role? When do foreign * Professor of Law, UNSW Sydney. ** Thurgood Marshall Professor of Constitutional Law, Harvard Law School. The authors thank Anna Dziedzic, Mark Graber, Bert Huang, David Feldman, Heinz Klug, Andrew Li, Joseph Marko, Sir Anthony Mason, Will Partlett, Iddo Porat, Theunis Roux, Amelia Simpson, Scott Stephenson, Adrienne Stone, Mark Tushnet, and Simon Young for extremely helpful comments on prior versions of the paper, and Libby Bova, Alisha Jarwala, Amelia Loughland, Brigid McManus, Lachlan Peake, Andrew Roberts, and Melissa Vogt for outstanding research assistance. -

The Toohey Legacy: Rights and Freedoms, Compassion and Honour

57 THE TOOHEY LEGACY: RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS, COMPASSION AND HONOUR GREG MCINTYRE* I INTRODUCTION John Toohey is a person whom I have admired as a model of how to behave as a lawyer, since my first years in practice. A fundamental theme of John Toohey’s approach to life and the law, which shines through, is that he remained keenly aware of the fact that there are groups and individuals within our society who are vulnerable to the exercise of power and that the law has a role in ensuring that they are not disadvantaged by its exercise. A group who clearly fit within that category, and upon whom a lot of John’s work focussed, were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In 1987, in a speech to the Student Law Reform Society of Western Australia Toohey said: Complex though it may be, the relation between Aborigines and the law is an important issue and one that will remain with us;1 and in Western Australia v Commonwealth (Native Title Act Case)2 he reaffirmed what was said in the Tasmanian Dam Case,3 that ‘[t]he relationship between the Aboriginal people and the lands which they occupy lies at the heart of traditional Aboriginal culture and traditional Aboriginal life’. A University of Western Australia John Toohey had a long-standing relationship with the University of Western Australia, having graduated in 1950 in Law and in 1956 in Arts and winning the F E Parsons (outstanding graduate) and HCF Keall (best fourth year student) prizes. He was a Senior Lecturer at the Law School from 1957 to 1958, and a Visiting Lecturer from 1958 to 1965. -

Speech by the Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma at the Networking Dinner Hosted by Tokyo ETO Seoul, Korea 23 September 2019

Speech by The Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma at the Networking Dinner hosted by Tokyo ETO Seoul, Korea 23 September 2019 The Rule of Law, the Common Law and Business: a Hong Kong Perspective 1. With the recent troubling events in Hong Kong, the focus has been on the rule of law. This concept is as important here in Korea as it is in Hong Kong. Hong Kong is a part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). On 1 July 1997, the PRC resumed the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong. The constitutional position of Hong Kong is contained in a constitutional document called the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. 1 It is significant in at least the following two respects: first, it states the principles reflecting the implementation of the PRC’s basic policies towards Hong 1 Promulgated and adopted by the National People’s Congress under the Constitution of the PRC. - 2 - Kong2 – the main one being the policy of “One Country Two Systems”; and secondly, for the first time in Hong Kong’s history, fundamental rights are expressly set out. These fundamental rights include the freedom of speech, the freedom of conscience, access to justice etc. 2. The theme of the Basic Law was one of continuity, meaning that one of its primary objectives was the continuation of those institutions and features that had served Hong Kong well in the past and that would carry on contributing to Hong Kong’s success in the future. -

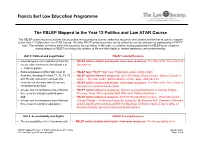

2020JAN Yr 12 PAL ATAR Course Mapped to the FBLEP.Docx

Francis Burt Law Education Programme The FBLEP Mapped to the Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course The FBLEP online resources include classroom/pre and post-visit resources, reference resources and student and teacher resources mapped to the Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course. All of the FBLEP online resources can be utilised by schools that are not participating in FBLEP visits. The activities and tasks within the resources are not reliant, in the main, on students having participated in FBLEP tours. However, participating in a FBLEP tour brings the syllabus to life and adds depth to student awareness and understanding. Unit 3: Political and Legal Power FBLEP Activity/Resource • Lawmaking process in parliament and the • FBLEP online student and teacher classroom resources: The Role of the Three Arms of courts, with reference to the influence of Government • Political parties • Roles and powers of the High Court of • FBLEP tour: FBLEP High Court Programme (when sitting in WA) Australia, including Sections 71, 72, 73, 75 • FBLEP online reference resources: 2010 Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture: ‘Being a Chapter 3 and 76 with reference to at least one Judge’ – The Hon. Justice Michael Barker, Lecture paper and Video file common law decision and at least one • FBLEP online student and teacher classroom resources: The Role of the Three Arms of constitutional decision Government (constitutional decision) • at least one contemporary issue (the last • FBLEP online reference resources: Non-Consensual Distribution of Intimate Images three years) relating -

'Executive Power' Issue of the UWA Law Review

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA LAW REVIEW Volume 43(2) March 2018 EXECUTIVE POWER ISSUE Introduction Dr Murray Wesson ............................................................................................................. 1 Executive Power in Australia - Nurtured and Bound in Anxiety The Hon Robert French AC ............................................................................................ 16 The Strange Death of Prerogative in England Thomas Poole .................................................................................................................... 42 Judicial Review of Non-Statutory Executive Action: Australia and the United Kingdom Amanda Sapienza .............................................................................................................. 67 Section 61 of the Commonwealth Constitution and an 'Historical Constitutional Approach': An Excursus on Justice Gageler's Reasoning in the M68 Case Peter Gerangelos ............................................................................................................. 103 Nationhood and Section 61 of the Constitution Dr Peta Stephenson ........................................................................................................ 149 Finding the Streams' True Sources: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication and Executive Power Joshua Forrester, Lorraine Finlay and Augusto Zimmerman .................................. 188 A Comment on How the Implied Freedom of Political Communication Restricts Non-Statutory Executive Power -

Justice John Toohey

Justice John Toohey During the April Holidays John XXIII College was privileged to host the memorial service for esteemed Alumni, Justice John Toohey. The following is a tribute published in the St Aloysius Newsletter, The Gonzagan on 1 May 2015. Another son of Western Australia died over the recent holidays. Former High Court Judge John Toohey, one of the fathers of native title, was part of the six-one majority in the Mabo case who triggered a subsequent revolution in land law in our nation. The Mabo Decision overturned the concept of terra nullius – that Australia was an empty land before European settlement – and stimulated the Commonwealth Government under Prime Minister Paul Keating to regulate the new legal environment under the Native Title Act. Justice Toohey served on the High Court from 1987 to 1998. What was not widely reported in the wake of Justice Toohey’s passing, was that he was the product of a Jesuit education. Toohey was born in 1930 and completed his secondary education at St Louis – the Jesuit boys’ school that operated between 1938 and 1976 in the western suburbs of Perth (in 1977 St Louis amalgamated with Loreto, Claremont to form the co-educational John XXIII College.) Justice Toohey completed Law and Arts at the University of Western Australian and, upon graduation, quickly became one of the leading young members of Western Australia’s small legal community. He founded his own law firm at the age of 24 and by the ages of 31, had appeared in the High Court as leading counsel. He took silk one year after going to the WA independent bar, however not before giving up his practice as a Perth barrister to establish the first Aboriginal Legal Office in Port Hedland. -

Could Rock Star Lawyers Carry Right Style for Barnaby Question? Advertisement

Today's Paper Markets Data SUBSCRIBE Home News Business Markets Street Talk Real Estate Opinion Technology Personal Finance Leadership Lifestyle All Home / Business / Legal Aug 17 2017 at 7:03 PM Updated Aug 17 2017 at 11:51 PM Save Article Print License Article Could rock star lawyers carry right style for Barnaby question? Advertisement Revellers at the High Court constitutional battle... no, wait, at Law Rocks last year. While we all wait for the High Court to declare Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce (and ever-growing company) qualified to sit in Parliament — we all know it "will so hold" because Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull says so — it does raise a serious access to justice question. by Katie Walsh Why can't matters of such public interest be determined, not by reference to nuanced arguments based on decades-old dissenting judgments*, but using a language everyone understands: music. Our lawyers, at least, are practising at this. On Thursday night, lawyers from some of the nation's biggest law firms took to the stage at Sydney's Oxford Art Factory to prove their mettle (and metal) in the court of public opinion, for the annual Law Rocks charity play-off to raise money for The Smith Family. This year Allens, Ashurst, Clayton Utz, DLA Piper, Johnson Winter & Slattery, King & Wood Mallesons, MinterEllison and Norton Rose Fulbright battled for honours. Related articles We eagerly await news of the final countdown – whether Aggravated Damage from Banks struggle to puzzle out the accountability jigsaw Clayton Utz lived up to its name, those grunge masters at 60FU overruled (calm down; that's obviously short for 60 Floors Up, where the KWM crew including M&A mix- Chevron settles ATO dispute for $1b plus master David Friedlander and banking DJ Ken Astridge reside in Governor Phillip AUSTRAC confirms terror links in CBA Tower), or last year's winners The Thorns (a name so good, Norton Rose is sticking case with it) pricked off everyone by taking the title again. -

Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture Judicial Review: Populism, the Rule of Law, Natural Justice and Judicial Independence

Francis Burt Law Education Programme Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture Judicial Review: Populism, the rule of law, natural justice and judicial independence Tuesday, 1 August 2017 5.30pm to 7.00pm Central Park Building Theatrette, Podium Level, 152-158 St Georges Terrace, Perth WA 6000 ABOUT THE PRESENTER Year 12 Politics and Law ATAR Course syllabus items to be addressed: The Hon Robert French AC was appointed Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia on Unit 3: Political and Legal Power 1 September 2008 and retired from that office • at least one contemporary issue (the last three years) relating on 29 January 2017. He is a graduate of the to political power and University of Western Australia in science and law. He was admitted in 1972 and practised • at least one contemporary issue (the last three years) relating as a barrister and solicitor in Western Australia to legal power until 1983 when he went to the Independent Unit 4: Accountability and rights Bar. He was appointed a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia in November 1986, an office he held until his • the accountability of the Commonwealth Parliament through appointment as Chief Justice on 1 September 2008. From 1994 judicial review to 1998 he was the President of the National Native Title Tribunal. In 2010, he was made a Companion in the Order of Australia and • the accountability of the Executive and public servants a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia. He is a through judicial review Founding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Law, a member of • the ways in which Australia and one other country can the American Law Institute, and an Honorary Life Member of the both uphold and/or undermine democratic principles, with Australasian Law Teachers Association, the Australasian Institute reference to: of Judicial Administration and the Australian Bar Association. -

Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture (Pdf 102Kb)

SIR RONALD WILSON LECTURE 19 MAY 2011 The Hon Justice Murray, Senior Judge, Supreme Court of WA THE DELIVERY OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE: BUILDING ON THE PAST TO MEET THE CHALLENGES OF THE FUTURE INTRODUCTION Mr President, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen. It is a very great honour to have been asked to deliver the Sir Ronald Wilson Lecture this year, although I appreciate that I am very much the second choice, and that I only got the gig because his Honour the Chief Justice is in Europe, attending a Court of the Future Program on courthouse design in the perhaps over-optimistic expectation that what he learns will be useful when, or if, the Supreme Court is provided with new accommodation of an appropriate standard to go with the 1903 Courthouse and to replace our tenancy in the former Royal Commission into WA Incorporated premises in an office building in the city. Of course, the mention of those premises recalls another link to Sir Ronald Wilson who, with the Hon Justice Kennedy, seconded from the Court, and the then recently retired judge, the Hon Peter Brinsden QC, served on that Royal Commission, which made such momentous findings on a wide range of Government activities and the people involved in them. I feel particularly intimidated when I observe that previous presenters of this lecture include people such as Sir Ronald himself, the Rt Hon Lord MacKay of Clashfern, the Rt Hon Sir Ninian Stephen, the Rt Hon Sir Zelman Cowen, Justice Michael Kirby, as he then was, and others, including local luminaries, the Hon Justice Robert French, as he then was, the Hon Justice Carmel McLure, Chief Judge Antoinette Kennedy, and the Hon Justice Michael Barker. -

Executive and Legislative Power in the Implementation of Intergovernmental Agreements

Advance Copy CRITIQUE AND COMMENT EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE POWER IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERGOVERNMENTAL AGREEMENTS T HE HON ROBERT FRENCH AC* The proliferation of intergovernmental agreements between the Commonwealth and the states raises questions about their characterisation as an exercise of Commonwealth exec- utive power and the legislative power necessary to give effect to them. This lecture, which celebrates Sir Anthony Mason’s outstanding contribution to the legal profession and the common law of Australia, reflects on the principal issues and outstanding questions relating to the implementation of such intergovernmental agreements. CONTENTS I Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 II Federalism and the Need for Cooperation ................................................................ 3 III Constitutional Provisions Requiring Intergovernmental Agreements .................. 5 IV The Use of Intergovernmental Agreements ............................................................. 10 V The Commonwealth Is Not Just Another Person ................................................... 12 VI A Question for Reflection .......................................................................................... 15 I INTRODUCTION This is the second occasion on which I have had the honour of delivering the Sir Anthony Mason Lecture at Melbourne University Law School. I have some- times complained about being asked to deliver lectures in honour of