Fred Harmon, Red Ryder, and Albuquerque's Little Beavertown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kiionize Geparunant Charges; Dr

'V'V, 1*. v if MONDAY, MARCH 21, 194t gpgtttng ijeraUi The Weather Average Dally N at’Fraaa Run FuraaaiM at U. 8. Haathar Buiaus Wm lb s Mm Ui oI Fabmuy. Ift* ahip o f J e m la that H glvoa man morning ineludod tho- nnthema f f,ip*thiwg to live op to,” Bav. Bfl- “Ood So Loved the Wortd" by Cloudy and vary warm this aft- Mrs. Major BlaseU of Stresses Need arannn; eccasloaal rala tonight, wlU be the special "P^okm *t ^ To Be Director gar continnad. * Moore and *T^rd Moat Holy” by 9,713 amllng Wadnrwlay mornlag aad 'jlljboulTo^ Friendship Circle of the Salvation m w maponalMlity la oura. Th to Roaaini sung by the South Ckurch Btambar o l «ko ^ n iM fnliowad by clrariai. Arm y tonight at 7:30 p.m. love thht Jeaua glvea to othom choir and the organ prelude "Ada For Friendship mfleets through their Uvea. Jeaua Baraaa a< OrmdaMaoa ^ ^T M n to a POMlbUtty that tht gio” (SonaU No. 8) by Haydn Manchester-^4 City of Village Charm "Tredowata,” a Polish movie, still glvea ua thla challenge today and the poatlude “Cantablle” (So ilfi^ m eompattUra to Uvo.up to the bbat that U In ua. iM n S tha aaoetln# ot WlU be shown this Sunday after naU No. 8) by Haydn played by noon at 3 o’clock In W hlU B ^ le Rev.’Edgar Preaches the Chapter, Order o( DeMo- "Jeaua aleo gave people aotne- Oeorge G.* Ashton, organist ot the AivtrM M ag an Fags 18) MANiCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, MARCH 22,1949 (FULItlELN FACES) FUICE FOUR CENTS ■-f^ tly. -

2 Buck Chuck Appaloosa Kid Bailey Boy A.M. Wiker Apple Pie Bakwudz

2 Buck Chuck Appaloosa Kid Bailey Boy A.M. Wiker Apple Pie Bakwudz Abbie Rose Arapaho Kid Bald Eagle Aces & Eights* Arctic Annie Bam Bam Acky Mace Arizona Cactus Kid Bandana Kid Adirondack Kid Arizona CoyDog Bandit Adorable Kissable Katie Arizona Desert Rose Bandito Bob Akarate Zach Arizona Nate Banker Bob Alabama Arizona Ranger Banning Bandit Alamo Kid Arizona Shootist Bar Stool Bob Alamo Red Arizona Thumber Barbwire Albuquerque Duke Arkansas Angel Barbwire Bill Alchimista Arkansas Blue Eyes Bar-E Ali Cat Arkansas Josh Bark River Kid Aliby Arkansas Muleskinner Barry James All Over Arkansas Outlaw Bart Star Alleluia Ruah Arkansas Smokey Bashful Alley Oop Artful Dodger Basket Weaver Alonzo Slim Ashes to Ashes Bass Reeves Alotta Lead Auburn Angel Bat Masterson Alvira Sullivan Earp AZ Filly Bean Counter Aly Oakley Aztec Annie Beans Amazing Grace B.A. Bear Amboy Kid B.S. Shooter Beardy Magee Ambrosia Baba Looey Beaver Creek Kid Ambush Baby Blue Bebop American Caliber Baby Boulder Beckaroo Ana Oakley Bacall Bee Stinger Angel Eyes Bad Bud Belle Angel Lady Bad Burro Beller The Kid Angel of Valhalla Bad Diehl Ben Quicker Angry Jonny Bad Eye Burns Ben Rumson Anna Belle Diamond Bad Eye Lefty* Ben Wayde Annabell Burns Bad Leg John Benny the Bullet Annie B. Goode Bad Leroy Bent Barrel Annie Moose Killer Bad Shot Baxter BFI Annie Wells Bad to the Bone Big Al Anton LeBear Badlands Bandit Big Bad John Apache Bob Badlands Ben Big Bear Appalachian Cowboy Badwater Bob Big Bill Appalachian Hillbilly Badwolf Bart Big D.J. Zent Big Ez BlackJack Jason Boulder -

CRYPTOQUOTE 10 Be of Use 38 Bamboo 17 Appealing to Provide the French Expression Commonly Used in English

BALDO by Cantu & Castellanos DOONESBURY by Garry Trudeau LUANN by Greg Evans MACANUDO by Liniers BEETLE BAILEY by Mort, Greg & Brian Walker FRAZZ by Jef Mallett BLONDIE by Dean Young & John Marshall GARFIELD by Jim Davis NON SEQUITUR by Wiley PEARLS BEFORE SWINE by Stephan Pastis PARDON MY PLANET by Vic Lee ZITS by Scott & Borgman by Mike Argirion & Jeff Knurek JUMBLE SUDOKU CROSSWORD by Thomas Joseph Complete the grid so that every row, column and 3x3 box contains every digit from 1 to 9 inclusively. ISAAC ASIMOV’S SUPER QUIZ 10-7 Score 1 point for each correct answer on the Freshman Level, Across 34 Can’t stand 9 Oboe parts 2 points on the Graduate Level and 3 points on the Ph.D. Level. 1 Uncertain 36 Sunset site 11 Catalog state 37 Hunting choices Subject: French Expressions 6 Flag feature goddess 15 Retina part CRYPTOQUOTE 10 Be of use 38 Bamboo 17 Appealing to Provide the French expression commonly used in English. 11 Caller’s need eater brainiacs (e.g., Literally, “white card.” Answer: Carte blanche.) 12 Rich cake 39 Collectible car 20 “Well, that’s H U X S J R E U H V H U E G K S 13 Corduroy 40 Kind of wave obvious!” Freshman level Graduate level Ph.D. level feature 41 Casual tops 21 “The Raven” 1. Literally, “false step.” 4. Literally, “I don’t 7. Literally, “already 14 Crocus cousin 42 Doesn’t writer 2. My god. know what.” seen.” 15 Jimmy’s budge 24 Book extras 3. Literally, “on the card” 5. -

Thomas Bentley Rue Platinum and Golden Age Comic Book and Adventure Strips Collection 2018.001

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8nc66v5 No online items Guide to the Thomas Bentley Rue Platinum and Golden Age Comic Book and Adventure Strips Collection 2018.001 Ann Galvan Historic Collections, J. Paul Leonard Library 2018 1630 Holloway Ave San Francisco, California 94132-1722 URL: http://library.sfsu.edu/historic-collections asc.2018.001 1 Contributing Institution: Historic Collections, J. Paul Leonard Library Title: Thomas Bentley Rue Platinum and Golden Age Comic Book and Adventure Strips Collection Source: Rue, Thomas Bentley, 1937-2016 Accession number: asc.2018.001 Extent: 18 Cubic Feet (17 boxes, 1 oversize box) Date (inclusive): 1938-1956 Abstract: The Thomas Bentley Rue Platinum and Golden Age Comic Book and Adventure Strips Collection features comics and adventure strips ranging from the 1930s to the 1950s. Language of Material: English Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Preferred Citation [Title], Thomas Bentley Rue Platinum and Golden Age Comic Book and Adventure Strips Archive, Historic Collections, J. Paul Leonard Library. Separated Materials A number of comic book reprints and compilations have been added to the J. Paul Leonard Library's general collection. A collection of Big Little Books are housed in Historic Collections within Special Collections. Immediate Source of Acquisition Gift of Virginia D.H. Rue In Memory of Thomas Bentley Rue, Accession number 2018/001. Conditions Governing Use Copyrighted. Transmission or reproduction of materials protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the copyright owner. In addition, the reproduction of some materials may be restricted by terms of gift or purchase agreements, donor restrictions, privacy and publicity rights, licensing and trademarks. -

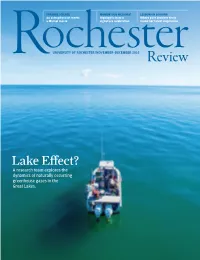

Lake E≠Ect? a Research Team Explores the Dynamics of Naturally Occurring Greenhouse Gases in the Great Lakes

STRANGE SCIENCE MOMENTOUS MELIORA! LESSONS IN LOOKING An astrophysicist meets Highlights from a Where poet Jennifer Grotz a Marvel movie signature celebration found her latest inspiration UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER /NovembER–DecembER 2016 Lake E≠ect? A research team explores the dynamics of naturally occurring greenhouse gases in the Great Lakes. RochRev_Nov2016_Cover.indd 1 11/1/16 4:38 PM “You have to feel strongly about where you give. I really feel I owe the University for a lot of my career. My experience was due in part Invest in PAYING IT to someone else’s generosity. Through the George Eastman Circle, I can help students what you love with fewer resources pursue their career “WE’RE BOOMERS. We think we’ll be aspirations at Rochester.” around forever—but finalizing our estate FORWARD gifts felt good,” said Judy Ricker. Her husband, —Virgil Joseph ’01 | Vice President-Relationship Manager, Ray, agrees. “It’s a win-win for us and the Canandaigua National Bank & Trust University,” he said. “We can provide for FOR FUTURE Rochester, New York ourselves in retirement, then our daughter, Member, George Eastman Circle Rochester Leadership Council and the school we both love.” GENERATIONS Supports: School of Arts and Sciences The Rickers’ charitable remainder unitrust provides income for their family before creating three named funds at the Eastman School of Music. Those endowed funds— two professorships and one scholarship— will be around forever. They acknowledge Eastman’s celebrated history, and Ray and Judy’s confidence in the School’s future. Judy’s message to other boomers? “Get on this bus! Join us in ensuring the future of what you love most about the University.” Judith Ricker ’76E, ’81E (MM), ’91S (MBA) is a freelance oboist, a business consultant, and former executive vice president of brand research at Market Probe. -

Campbell and Captain Conquer Barrel Daze

BARREL RACING REPORT - Fast Horses, Fast News since 2007 - Volume 5, Issue 15 www.barrelracingreport.com April 12, 2011 Campbell and Captain Conquer Barrel Daze VGBRA Barrel Daze Futurity April 8-10, 2011, Walla Walla, WA DASH FOR CASH FIRST DOWN DASH SI 114 Futurity Average SI 105 FIRST PRIZE ROSE 1D 1 KR Captain Jack, Danyelle Campbell, , 28.662, $2,686.60 SI 98 07 g. Dash Ta Fame-Tiny Cultured Pearl DASH TA FAME SI 113 THE RUNDOWN: DANYELLE CAMPBELL TINY’S GAY SUDDEN FAME SI 106 HORSE: KR Captain Jack SI 98 Bay Gelding, 4 Years Old, 15.2 hands, 1250 lbs. BAR DEARIE SI 90 HORSE HISTORY: I actually bought him last year from Bo Hill, she KR CAPTAIN JACK was the one who started him on the barrels. I wasn’t looking for a 2007 BAY GELDING horse when I saw him because I usually don’t buy started horses EASY JET and people told me they didn’t think she’d sell him. When I saw EASY SAINT SI 100 him, he just caught my eye, so I walked up to her and I told her I SI 107 know everything you have is for sale so what do you want for him. LA JOLLA He just really grabs peoples attention. I have never had a horse so TINY CULTURED PEARL SI 90 SI 87 many people wanted to buy. It has taken a while to get him used to GOOD PACIFIC my training, but he always tries hard. Bo did an amazing job start- GOODS TINY COAT SI 82 ing him and getting him going and a lot of the credit for him goes to her. -

2020 Jbba National Show and Convention Show And

2020 JBBA NATIONAL SHOW AND CONVENTION SHOW AND CONTEST RESULTS National Show National Heifer Show Class: 01 - Heifers born March 1 - March 31, 2020 Brooks, Weston - 218 Entry# Name: CF 0436 C1124339 DOB: 3/2/2020 Green Sire: 1 China, TX 969 CF Bravado C1073659 Calf DOB: Dam: CF 843/5 C1059725 Calf ID: Division Cham Scherer, Caeden - 29 Entry# Name: CF 434/0 C1123541 DOB: 3/26/2020 Green Sire: 2 Brenham, TX 471 CF Riptide C1045544 Calf DOB: Dam: CF 701/3 C1034227 Calf ID: Bouchard, Graicie - 77 Entry# Name: BB Sandy C1123543 DOB: 3/20/2020 Green Sire: 3 Azle, TX 1020 Shiner Britches C1092159 Calf DOB: Dam: BB Faith C1093989 Calf ID: Byers, Camrin - 33 Entry# Name: Diamond B Poppy C1123249 DOB: 3/14/2020 Green Sire: 4 Henrietta, TX 828 Logan's Britches C1072112 Calf DOB: Dam: Sprinkles C1041434 Calf ID: Dallmeyer, Keely - 106 Entry# Name: Phoebe C1123879 DOB: 3/12/2020 Green Sire: 5 Ledbetter, TX 1055 Teddy Bear C1049053 Calf DOB: Dam: Babycakes C1049811 Calf ID: Scherer, Caeden - 29 Entry# Name: CF 438/0 C1124711 DOB: 3/3/2020 Green Sire: 6 Brenham, TX 470 CF Riptide C1045544 Calf DOB: Dam: C1051524 Calf ID: Scherer, Caeden - 29 Entry# Name: CHS 043 C1123538 DOB: 3/10/2020 Green Sire: 7 Brenham, TX 472 CF Riptide C1045544 Calf DOB: Dam: CF 641/5 C1050140 Calf ID: Calaway, Lynleigh - 137 Entry# Name: LC-Denali C1121861 DOB: 3/17/2020 Green Sire: 8 Ivanhoe, TX 68 55/16 C1072453 Calf DOB: Dam: WR Bee Bee C1094766 Calf ID: Low, Makenzie - 149 Entry# Name: L5 Ella C1122624 DOB: 3/11/2020 Green Sire: 9 Alto, TX 47 EMS Bet on Bubba C1053095 -

Editor & Publisher International Year Books

Content Survey & Selective Index For Editor & Publisher International Year Books *1929-1949 Compiled by Gary M. Johnson Reference Librarian Newspaper & Current Periodical Room Serial & Government Publications Division Library of Congress 2013 This survey of the contents of the 1929-1949 Editor & Publisher International Year Books consists of two parts: a page-by-page selective transcription of the material in the Year Books and a selective index to the contents (topics, names, and titles) of the Year Books. The purpose of this document is to inform researchers about the contents of the E&P Year Books in order to help them determine if the Year Books will be useful in their work. Secondly, creating this document has helped me, a reference librarian in the Newspaper & Current Periodical Room at the Library of Congress, to learn about the Year Books so that I can provide better service to researchers. The transcript was created by examining the Year Books and recording the items on each page in page number order. Advertisements for individual newspapers and specific companies involved in the mechanical aspects of newspaper operations were not recorded in the transcript of contents or added to the index. The index (beginning on page 33) attempts to provide access to E&P Year Books by topics, names, and titles of columns, comic strips, etc., which appeared on the pages of the Year Books or were mentioned in syndicate and feature service ads. The headings are followed by references to the years and page numbers on which the heading appears. The individual Year Books have detailed indexes to their contents. -

2020 Residential Sales Report

2020 RESIDENTIAL SALES REPORT PARCEL #: 004-01-0494-000 C-300 ADDRESS: 511 N HOLBROOK SQ FT: 2,282 SALE DATE: 07/28/2017 GAR SQ FT: 624 SALE PRICE: $325,000.00 SELLER: HUDDAS, PATRICIA A BUYER: SEEKE, SCOTT-ELIZABETH PARCEL #: 010-08-0013-000 R-010 ADDRESS: 1432 PALMER SQ FT: 2,540 SALE DATE: 12/03/2018 GAR SQ FT: 504 SALE PRICE: $485,000.00 SELLER: GIERADA, KYLE- STEPHANIE BUYER: BURR, ELIZABETH PARCEL #: 010-08-0011-000 R-010 ADDRESS: 1400 PALMER SQ FT: 1,746 SALE DATE: 08/08/2018 GAR SQ FT: 516 SALE PRICE: $360,000.00 SELLER: PIERCE FAMILY TRUST BUYER: STENGLE, DANIEL- MARILYN PARCEL #: 010-08-0014-000 R-010 ADDRESS: 1448 PALMER SQ FT: 1,944 SALE DATE: 04/30/2018 GAR SQ FT: 462 SALE PRICE: $365,000.00 SELLER: PURSELL, PHILIP-PAVLA BUYER: PARDINGTON, CLAIRE PARCEL #: 010-08-0028-000 R-010 ADDRESS: 1480 HARTSOUGH SQ FT: 1,705 SALE DATE: 12/11/2017 GAR SQ FT: 420 SALE PRICE: $285,000.00 SELLER: ASAM, SUSAN E BUYER: LANG-KAZI, KYLE-VILAYATHUSEN PARCEL #: 010-08-0044-000 R-010 ADDRESS: 1381 PALMER SQ FT: 1,963 SALE DATE: 05/13/2017 GAR SQ FT: 388 SALE PRICE: $327,000.00 SELLER: NICHOLS, BERNICE BUYER: SULLIVAN III, EDWARD 2020 RESIDENTIAL SALES REPORT PARCEL #: 011-04-0028-000 R-030 ADDRESS: 655 BYRON SQ FT: 1,040 SALE DATE: 07/13/2018 GAR SQ FT: 280 SALE PRICE: $275,000.00 SELLER: COLE, MATHEW D- BRITTANY BUYER: MILLER, JEFF WHALEN PARCEL #: 011-04-0039-000 R-030 ADDRESS: 620 BYRON SQ FT: 1,284 SALE DATE: 04/06/2018 GAR SQ FT: 440 SALE PRICE: $225,000.00 SELLER: GOLOVOY, AMY JO (LIVING TRUST) BUYER: MERRIFIELD PROPERTIES PARCEL #: 011-04-0009-000 -

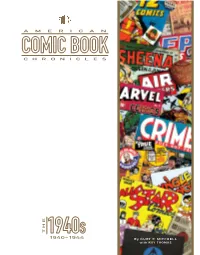

A M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S the 1940-1944

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1940-1944 By KURT F. MITCHELL with ROY THOMAS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles ................. 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data ......................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowledgements ............. 6 Chapter One: 1940 Rise of the Supermen ......................................... 8 Chapter Two: 1941 Countdown to Cataclysm ...............................62 Chapter Three: 1942 Comic Books Go To War................................ 122 Chapter Four: 1943 Relax: Read the Comics ................................ 176 Chapter Five: 1944 The Paper Chase ............................................. 230 Works Cited ...................................................... 285 Index ................................................................. 286 Rise of the Supermen America on January 1, 1940, was a nation on edge. Still suffering the aftershocks of the Great Depression despite Franklin D. Roosevelt’s progressive New Deal nos- trums—unemployment stood at 17% for 1939—Americans eyed the expanding wars in Europe and Asia nervously. Some tried to dismiss Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini as comic opera buffoons, decrying the hostilities as a “phony war” because not much had happened since the blitzkrieg dismemberment of Poland the previous September. These naysayers did not see it for what it was: the calm before the storm. Before the first year of the new decade was out, Nazi Germany seized Norway, Denmark, Belgium, the Nether- lands, and ultimately France, while attempting to bomb the United Kingdom into subjection. The British held out defiantly, and Hitler reluctantly abandoned his plans to invade England. That small victory brought no cheer to the conquered nations, where Der Führer’s relentless oppres- sion of Jews and other scapegoated minorities was in full force. Il Duce, too, continued his aggression, as Fascist Italy invaded Egypt and Greece. -

A Review of Movie Comics

Nicolas Labarre, ‘Coming to Life: A Review of Movie Comics: THE COMICS GRID Page to Screen/Screen to Page’ (2017) 7(1): 3 The Comics Journal of comics scholarship Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, DOI: https://doi. org/10.16995/cg.105 REVIEW Coming to Life: A Review of Movie Comics: Page to Screen/Screen to Page Movie Comics: Page to Screen/Screen to Page, Blair Davis, Rutgers University Press, 295 pages, 2017, ISBN: 978-0- 8135-7225-3 Nicolas Labarre University Bordeaux Montaigne, FR [email protected] This book review provides an overview of Movie Comics: Page to Screen/ Screen to Page by Blair Davis (Rutgers University Press, 2017) a book which examines the reciprocal adaptations of film into comics and com- ics into films from 1930 to 1960. This review argues that Movie Comics provides a useful and finely-textured cultural history of that phenomenon, which help contextualize scholarly studies of contemporary adaptations and transmedia constructions. Keywords: adaptation; comics; film; serials; transmedia Movie Comics: Page to Screen/Screen to Page (Davis 2017; Figure 1) is part of an ongoing surge of academic interest for the adaptation of comics into movies. In 2016 alone, books such as The Modern Superhero in Film and Television (Brown 2016), Mar- vel Comics into Film (McEniry et al. 2016), Panel to the Screen (Morton 2016), The Comic Book Film Adaptation (Burke 2016) and Comic – Film – Gender (Sina 2016) have all sought to examine the intermedial relationship between film and comics, from a variety of angles. Several other publications have also tackled the sprawling transmedia narratives elaborated around contemporary superhero films, of which comics are a vital component. -

Footwear Clearance

-•sr k o »Y W i!fr r WEOME8DAT, FEBRUARY 25 ,1 9 4 8 ...... iOanrtrrBtfr £t>rnitt0 ll^rald A vtiaft Daily areatathm J . V , be Ika Maatk at Jaanafg. 1M8 | Luther Oiapia, of STS Middle Dr. Matthew Splnka, urofaasor Plan to Discuss TurepUM, east, has undargona a of (jhrUtlaa History at the Hart 9 ,4 5 2 Al>ont Town second o^ratkm at tbs U. 8. Ma ford Theological Seminary, win be rina hoi^tal at (3ifton. SUtan the speaker at the meeting tomor Parking Problem Island, New York. Hia prograsa row evening at i o’clock in On- CRAFTSMAN Mr. M i Mtm. John F. Ptcklos of has baen conalderaUy slower than ter church. This will be the third M anchetier-^A City o f Village Charm SOB Otnet rocolTad atwo of tbo in the series on "Our Faith, Our An open forum on the parking was expected. Mr. diapin wlahas P B K l f O I J i * Mrth yooUrdoy o f tbolr oocoimI to thank hla friends who aent FeUowshlp, Our Freedom." Dr. problem will b* held at the next (EIGHTEEN PAGES) grandchUO, • oon, bom at Aultman cards and letters to him at the Spinks's topic will be "Beginnings meeting of the Manchetser Im AUTO BOOT SHOP A4aartlMsg mm Fage 14) MANCHESTER, CONNn THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 26,1948 bMiUl, duton, Ohio, to Mr. and of CongregationaUam in America." provement aasociatlon, acheduled yO L. LXV n., NO. 12S Mra. W im m Howard Plcklea. hoepital. DUEEWr BEOTHEE8 SS3-SS4 CHABTEB OAE ST. Mlaa Louise Lehr wUl be the aolo- to be held at Lithuanian hall on EXPEBT PAINTINO AND COLOB BLENOtMO lira.