A Review of Movie Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Peanuts Volume I by Charles M. Schulz

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators STUDY GUIDE: THE COMPLETE PEANUTS by Charles M. Schulz Volume One: 1950-1952 Study guide written by Art Baxter Introduction America was in the throes of post-war transition in 1950. Soldiers had returned home, started families and abandoned the cities for the sprawling green lawns of newly constructed suburbia. They had sacrificed during the Great Depression and subsequent war effort and this was their reward. Television was beginning to replace the picture-less radio not to mention live theater, supper clubs and dance halls, as Americans stayed home and raised families. Despite all this “progress” an empty feeling still resided in the pit of the American soul. Psychology, that new science that had recently gone mainstream, tried to explain why. Then, Charles M. Schulz’s little filler comic strip, Peanuts, appeared in the funny pages. Schulz was born in 1922, the solitary child of a barber and his wife, in St. Paul, Minnesota. Sparky, his lifelong nickname, was given to him when he was an infant, by an uncle, after the comic strip character Barney Google’s racehorse Spark Plug. Schulz had an early love and talent for drawing. He enjoyed famous comic strips like Roy Crane’s Wash Tubbs/Captain Easy (1924- 1943), the prototype of the adventure strip; E. C. Segar’s Thimble Theater (1919-1938), and its diverse cast of colorful characters going in and out rollicking adventures; and Percy Crosby’s Skippy (1925-1945) with its wise-for-his-age perceptive child protagonist. Schulz was a bright student and skipped several grades, making him the youngest and smallest in his class. -

A Finding Aid to the Berryman Family Papers, 1829-1984, Bulk 1882-1961, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Berryman Family Papers, 1829-1984, bulk 1882-1961, in the Archives of American Art Jean Fitzgerald 1993 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Clifford and Kate Berryman Papers, 1829-1963, undated........................ 5 Series 2: Florence Berryman Papers, 1902-1984.................................................. 22 Series 3: Jim Berryman Papers, 1919-1964, undated........................................... 26 Berryman family papers AAA.berrfami Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Kiionize Geparunant Charges; Dr

'V'V, 1*. v if MONDAY, MARCH 21, 194t gpgtttng ijeraUi The Weather Average Dally N at’Fraaa Run FuraaaiM at U. 8. Haathar Buiaus Wm lb s Mm Ui oI Fabmuy. Ift* ahip o f J e m la that H glvoa man morning ineludod tho- nnthema f f,ip*thiwg to live op to,” Bav. Bfl- “Ood So Loved the Wortd" by Cloudy and vary warm this aft- Mrs. Major BlaseU of Stresses Need arannn; eccasloaal rala tonight, wlU be the special "P^okm *t ^ To Be Director gar continnad. * Moore and *T^rd Moat Holy” by 9,713 amllng Wadnrwlay mornlag aad 'jlljboulTo^ Friendship Circle of the Salvation m w maponalMlity la oura. Th to Roaaini sung by the South Ckurch Btambar o l «ko ^ n iM fnliowad by clrariai. Arm y tonight at 7:30 p.m. love thht Jeaua glvea to othom choir and the organ prelude "Ada For Friendship mfleets through their Uvea. Jeaua Baraaa a< OrmdaMaoa ^ ^T M n to a POMlbUtty that tht gio” (SonaU No. 8) by Haydn Manchester-^4 City of Village Charm "Tredowata,” a Polish movie, still glvea ua thla challenge today and the poatlude “Cantablle” (So ilfi^ m eompattUra to Uvo.up to the bbat that U In ua. iM n S tha aaoetln# ot WlU be shown this Sunday after naU No. 8) by Haydn played by noon at 3 o’clock In W hlU B ^ le Rev.’Edgar Preaches the Chapter, Order o( DeMo- "Jeaua aleo gave people aotne- Oeorge G.* Ashton, organist ot the AivtrM M ag an Fags 18) MANiCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, MARCH 22,1949 (FULItlELN FACES) FUICE FOUR CENTS ■-f^ tly. -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Aesthetics, Taste, and the Mind-Body Problem in American Independent Comics

PAPER TOWER: AESTHETICS, TASTE, AND THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM IN AMERICAN INDEPENDENT COMICS William Timothy Jones A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton © 2014 William Timothy Jones All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Comics studies, as a relatively new field, is still building a canon. However, its criteria for canon-building has been modeled largely after modernist ideas about formal complexity and criteria for disinterested, detached, “objective” aesthetic judgment derived from one of the major philosophical debates in Western thought: the mind-body problem. This thesis analyzes two American independent comics in order to dissect the aspects of a comic work that allow it to be categorized as “art” in the canonical sense. Chris Ware’s Building Stories is a sprawling, Byzantine comic that exhibits characteristically modernist ideas about the subordination of the body to the mind and art’s relationship to mass culture. Rob Schrab’s Scud: The Disposable Assassin provides a counterpoint to Building Stories in its action-heavy stylistic approach, developing ideas about the merging of the mind and the body and the artistic and the commercial. Ultimately, this thesis advocates for a re -evaluation of comics criticism that values the subjective, emotional, and the popular as much as the “objective” areas of formal complexity and logic. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anna O’Brien, for the original germ of this idea and hours of enlightening conversation and companionship. To Jeremy Wallach and Esther Clinton, whose emphatic response to the paper that eventually became this thesis was instrumental to my belief in the quality of my work. -

2 Buck Chuck Appaloosa Kid Bailey Boy A.M. Wiker Apple Pie Bakwudz

2 Buck Chuck Appaloosa Kid Bailey Boy A.M. Wiker Apple Pie Bakwudz Abbie Rose Arapaho Kid Bald Eagle Aces & Eights* Arctic Annie Bam Bam Acky Mace Arizona Cactus Kid Bandana Kid Adirondack Kid Arizona CoyDog Bandit Adorable Kissable Katie Arizona Desert Rose Bandito Bob Akarate Zach Arizona Nate Banker Bob Alabama Arizona Ranger Banning Bandit Alamo Kid Arizona Shootist Bar Stool Bob Alamo Red Arizona Thumber Barbwire Albuquerque Duke Arkansas Angel Barbwire Bill Alchimista Arkansas Blue Eyes Bar-E Ali Cat Arkansas Josh Bark River Kid Aliby Arkansas Muleskinner Barry James All Over Arkansas Outlaw Bart Star Alleluia Ruah Arkansas Smokey Bashful Alley Oop Artful Dodger Basket Weaver Alonzo Slim Ashes to Ashes Bass Reeves Alotta Lead Auburn Angel Bat Masterson Alvira Sullivan Earp AZ Filly Bean Counter Aly Oakley Aztec Annie Beans Amazing Grace B.A. Bear Amboy Kid B.S. Shooter Beardy Magee Ambrosia Baba Looey Beaver Creek Kid Ambush Baby Blue Bebop American Caliber Baby Boulder Beckaroo Ana Oakley Bacall Bee Stinger Angel Eyes Bad Bud Belle Angel Lady Bad Burro Beller The Kid Angel of Valhalla Bad Diehl Ben Quicker Angry Jonny Bad Eye Burns Ben Rumson Anna Belle Diamond Bad Eye Lefty* Ben Wayde Annabell Burns Bad Leg John Benny the Bullet Annie B. Goode Bad Leroy Bent Barrel Annie Moose Killer Bad Shot Baxter BFI Annie Wells Bad to the Bone Big Al Anton LeBear Badlands Bandit Big Bad John Apache Bob Badlands Ben Big Bear Appalachian Cowboy Badwater Bob Big Bill Appalachian Hillbilly Badwolf Bart Big D.J. Zent Big Ez BlackJack Jason Boulder -

DON DAVIS: –40 Horsepower and Again Going Back to Cajun Ingenuity, Which I Bet Your Grandfather Can Help Us With–

DON DAVIS: –40 horsepower and again going back to Cajun ingenuity, which I bet your grandfather can help us with– CLIFFORD SMITH: Oh without a doubt. DAVIS: –they just figured out how to put it in but it had a – I don‟t know if you‟ve ever seen it yet – he‟d crank them this way. Alright, well you had to get up and crank them. Well if you miscranked you broke your arm. And I‟m sure and so before we leave we‟d like very much if you don‟t mind giving us the contact information and if you wouldn‟t object to just, you know, college professor types coming in and doing exactly what we‟re doing here. CARL BRASSEAUX: Harassing him like that. DD: But if we don‟t it‟s gonna stay in the DeHart family and fifty years from now when that kind of information will be probably very important we‟ll have nobody to talk to. CS: He can give you the whole history of the mechanical application– DD: Aw that‟s– CS: –of engines from the – I‟m telling you he grew up down the bayou. I bet you would – her grandfather grew up – her grandfather about the same age as I am and he probably can remember cause, I mean, he grew up down the bayou. I mean, I grew up on the bayou. He can tell you about people living in houseboats. They didn‟t live on the land; they lived in houseboats. They lived, again, they would oar out to (? 01:26) because, again, he knows this, his grandfather knows this, but before you had an engine that boomed a boat continuously – you didn‟t have a trawl. -

Mtv and Transatlantic Cold War Music Videos

102 MTV AND TRANSATLANTIC COLD WAR MUSIC VIDEOS WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH INTRODUCTION In 1986 Music Television (MTV) premiered “Peace Sells”, the latest video from American metal band Megadeth. In many ways, “Peace Sells” was a standard pro- motional video, full of lip-synching and head-banging. Yet the “Peace Sells” video had political overtones. It featured footage of protestors and police in riot gear; at one point, the camera draws back to reveal a teenager watching “Peace Sells” on MTV. His father enters the room, grabs the remote and exclaims “What is this garbage you’re watching? I want to watch the news.” He changes the channel to footage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the 1986 nuclear arms control summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. The son, perturbed, turns to his father, replies “this is the news,” and lips the channel back. Megadeth’s song accelerates, and the video re- turns to riot footage. The song ends by repeatedly asking, “Peace sells, but who’s buying?” It was a prescient question during a 1980s in which Cold War militarism and the nuclear arms race escalated to dangerous new highs.1 In the 1980s, MTV elevated music videos to a new cultural prominence. Of course, most music videos were not political.2 Yet, as “Peace Sells” suggests, dur- ing the 1980s—the decade of Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and a robust nuclear arms race—music videos had the potential to relect political concerns. MTV’s founders, however, were so culturally conserva- tive that many were initially wary of playing African American artists; addition- ally, record labels were hesitant to put their top artists onto this new, risky chan- 1 American President Ronald Reagan had increased peace-time deicit defense spending substantially. -

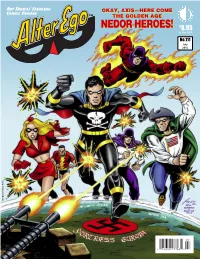

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brian S. Mosher for the degree of Master of Arts in English on May 28, 2013 Title: Comics in the Classroom Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________________________ Lisa S. Ede As the necessity grows for undergraduate English teachers to incorporate various multimodal texts into their course material due to the changing landscape of what is considered English studies, comics can be an increasingly viable source for such texts. This thesis introduces several formal qualities of comics available for teachers to draw upon and add to their own arsenal of critical and terminological vocabulary in order to deploy comics-specific pedagogical material. A history of comics' problematic history and growth is provided as well as several examples of the sophistication of comics texts. In addition, specific information is given on how several comics might be incorporated into common undergraduate courses, and guidance for teachers is provided through extended examples of comics' value for English courses. ©Copyright by Brian S. Mosher May 28, 2013 All Rights Reserved Comics in the Classroom by Brian S. Mosher A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented May 28, 2013 Commencement June 2013 Master of Arts thesis of Brian S. Mosher presented on May 28, 2013. APPROVED: _________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English _________________________________________________________ Director of the School of Writing, Literature, and Film _________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes release of my thesis to any reader upon request.