VARIED TYPES This Edition, Printed by the Town Talk Press, Is Limited to Seventy-Five Copies, Signed by the Author, of Which This Is VARIED TYPES BY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 by BENJAMIN DE CASSERES

Boolcs and the Book World of The Sun, December 7, 1919. 15 Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 By BENJAMIN DE CASSERES. written, you know. I have just sent down ASTWARD the star of literary cm-- town for one of my books, want 'A J and I pire takes its way. After twenty-liv-e to paste a photograph as well as auto- years Ina Donna Coolbrith, crowned graph in it to mail to you. poet laureate of California by the Panama-P- "The old Oakland literary days! Do acific Exposition, has returned to yon know you were the first. one who ever New York. Her house on Russian Hill, complimented me on my choice of reading San Francisco, the aristocratic Olympus matter? Nobody at home bothered then-hea- of the Musaj of the Pacific slope, stands over what I read. I was an eager, empty. thirsty, hungry little kid and one day It is as though California had closed a k'Prsmmm mm m:mmm at the library I drew out a volume on golden page of literary and artistic mem- Pizzaro in Pern (I was ten years old). ories in her great epic for the life of You got the book and stamped it for me; Miss Coolbrith 'almost spans the life of and as you handed it to me you praised California itself. Her active and acuto me for reading books of that nature. , brain is a storehouse of memories and "Proud ! If you only knew how proud ' anecdote of those who have immortalized your words made me! For I thought a her State in literature Bret Harte, Joa- great deal of you. -

The Outpouring of Support

Sir Harold Evans Sir Harold Evans was the editor of The Sunday Times from 1967 to 1981 and the Times in 1981. From 1990 until 1997, he was the president and publisher of Random House, and later the editorial director for US News and World Report, the New York Daily News, and The Atlantic Monthly. He edited three books by Henry Kissinger, My American Journey by Colin Powell, Game Plan: How to Conduct the U.S. Soviet Contest by Zbiginew Brzezinski; Debt and Danger: The World Economic Crisis by Harold Lever; and The Yom Kippur War by The Insight Team of The Sunday Times. He is additionally the author, in association with Edwin Taylor, of Pictures on a Page. Continuously in print for 37 years, the publication is the culmination of a five-volume series on editing and design featuring interviews by Henri Cartier Bresson, Bert Stern, Harry Benson, Bill Brandt, Eddie Adams, Andre Kertesz, Eugene Smith, and Richard Avedon. Evans' best known work, The American Century, won critical acclaim when published in 1998, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for 10 weeks. The sequel, They Made America (2004), describes the lives of some of the country's most important inventors and innovators, and was named by Fortune as one of the best books in the 75 years of that magazine's publication. The latter was adapted as a four-part television mini-series that same year and as a National Public Radio special in the USA in 2005. sirharoldevans.com Dedicated to the public exploration of the early history of New Amsterdam and New York City April 1, 2020 Hon. -

Contents Part One Page Pioneer Voices

Copyright McClur Co . A . C. g I91 7 em e 1 1 Published N ov b r , 9 7 M . N D L . L . A . L A R . To . M . G J , . TO OTHER FRIENDS I N SANTA BARBARA W HO TAU G HT M E T HE LOVELINESS OF CALIFORNIA CONTENTS P art One PAGE PIONEER VOICES Part T wo VOICES OF THE GREAT SING ERS Part T hree LIVI NG VOICES INTRODUCTION IN PREPARI NG this collection o f verse for publi ha two ! cation , I have d purposes first , to make an — - interesting book the ancient and ever living pur f l e —and pose o al makers O f good literatur second , to give to all who may desire it a volume of poems that sing and celebrate the traditions, the life , and the natural beauty o f one o f the greatest common n r wealths in the union . The roma ce and ha dship, the gayety an d the heroism o f the days o f the padres a and the later pioneers , the adventurous d sh and ’ o f -niners flare the forty , the rich , golden health and prosperity o f all the days that have followed the pioneer period — all these things are most vivid and colorful history an d tradition and have had no smal l part in creating for Californians that heritage o f naive and fierce affection — belligerent devotion to — their commonwealth and its life and customs by which they are known and with which they startle the quieter and cooler hearts o f men and women o f r o f mo e staid and sober states . -

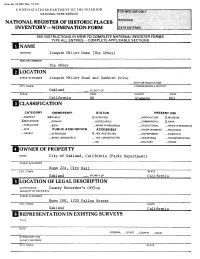

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Joaquin Miller Home (The Abbey) AND/OR COMMON The Abbey LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Joaquin Miller Road and Sanborn Drive _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Oakland _.. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 AT ameda 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XXPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM J^BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Oakland, California (Parks Department) STREET & NUMBER Room 224, City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Oakland VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE, County Recorder ! s Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER Room 100^ 1225 Fallen Street CITY. TOWN STATE Oakland California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE .FEDERAL _STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XXORIGINALSITE _MOVED DATE. X-GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Joaquin Miller House is a small three-part frame building at the foot of the steep hills East of Oakland California. Composed of three single rooms joined together, the so-called "Abbey" must be seen as the most provincial of efforts to impose gothic-revival detail upon the three rooms. -

What the American Medical Association Thinks of the Electronic Reactions of Abrams

WHAT THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION THINKS OF THE ELECTRONIC REACTIONS OF ABRAMS. ALBERT ABRAMS, A. M., M. D., LL. D., F. R. M. S. FOREWORD Dr. Albert Abrams of San Francisco is the latest rocket to blaze a somewhat polychromatic course across the firma ment of pseudo-medicine. The stick will fall, anon. In the field of diagnosis Dr. Abrams claims to have evolved a system of abdominal percussion, practiced in connection with certain electrical apparatus he has made, from which he derives what he is pleased to term the “Electronic Reactions of Abrams” (abbreviated E. R. A.). By means of this system it is claimed that Abrams ‘ ‘ can diagnose the sex, race and disease” of a patient he has never seen. All that he needs is a sample of blood from the individual. A few drops of blood, from a person who must be facing west but who may be a thousand miles or more away, are put on a piece of paper and the paper is placed in what Abrams calls his “Dynamizer.” This is connected with his “Rheostatic Dynamizer,” from which, in turn, wires go to the “Vibratory Rate Rheostat” that is connected with the “Measuring Rheostat!” From the “Measuring Rheo stat” comes a wire at the end of which is an electrode which is pressed to the forehead of a healthy individual (the “subject”) whose abdomen is being percussed. The “subject” must face west, also. The whole arrangement is reminiscent of one of Gold berg’s inimitable cartoons, depicting a fearful and wonder ful device for waking up in the morning or committing suicide or something equally interesting. -

The American Side of the Line: Eagle City's Origins As an Alaska Gold Rush Town As

THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town As Seen in Newspapers and Letters, 1897-1899 National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town National Park Service Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve 2019 Acknowledgments I want to thank the staff of the Alaska State Library’s Historical Collections, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives, the University of Washington’s Special Collections, and the Eagle Historical Society for caring for and making available the photographs in this volume. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska February 2019 Front Cover: Buildings in Eagle’s historic district, 2007. The cabin (left) dates from the late 1890s and features squared-off logs and a corrugated metal roof. The red building with clapboard siding was originally part of Ft. Egbert and was moved to its present location after the fort was decommissioned in 1911. Both buildings are owned by Dr. Arthur S. Hansen of Fairbanks. Photograph by Chris Allan, used with permission. Title Page Inset: Map of Alaska and Canada from 1897 with annotations in red from 1898 showing gold-rich areas. Note that Dawson City is shown on the wrong side of the international boundary and Eagle City does not appear because it does not yet exist. Courtesy of Library of Congress (G4371.H2 1897). Back Cover: Miners at Eagle City gather to watch a steamboat being unloaded, 1899. -

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives Grades: 7-HS Subjects: History, Oregon History, Civics, Social Studies Suggested Time Allotment: 1-2 class periods Lesson Background: Our impressions of events can often be influenced by the manner in which they are reported to us in the media. Begin by staging a class discussion of some recent news event(s) that have caused controversy. Can the students think of any news stories that strongly divide public opinions? Any that have been reported in a variety of different ways, depending on which television channels you watch or magazines you read? Can they think of examples where they thought one way or formed a certain opinion about a certain news event, only to have their minds change and opinion shift later, when more information came to light in the media? Moving on from this discussion, the lesson can demonstrate these issues of perspective. Lesson #1: Joaquin Miller—Genius or Cad? Joaquin Miller was the pen name of Cincinnatus Heine Miller, a colorful and controversial poet of the nineteenth century. (Read a detailed biography of Joaquin Miller on Wikipedia, here.) Known in his day as the ‘Poet of the Sierras,’ the ‘Byron of the Rockies,’ and the ‘Bard of Oregon,’ Miller became a celebrity throughout the United States, and especially in England. He was an associate of such enduring literary figures as Ambrose Bierce and Brett Hart. However, it could be argued that Miller’s fame came more from the popular image he created for himself—frontiersman, outdoorsman—than from the actual quality of his literary work. -

The Pioneer News, 1916 - 1917, J

The Pioneer News, 1916 - 1917, J. W. Barrall, Editor Transcribed from Microfilm by Edith Blissett in the year 2003 January 5, 1917 Trustee Sex Barger. grandchild, Lewis Earl Colvin, and Mr. and Mrs. H. T. Miller. Mrs. Mary Masden, of Lebanon ***Educational Jottings She received many handsome Junction, was recently married to presents, among them a beautiful Misses Lillian Thompson, Gladys Mr. John Boots, a well-known bouquet of carnations given by Welch, Edna Starks, Varina farmer of Belmont. The bride is her daughter, Mrs. Clara Joyce of Mudd, Elizabeth Cash, Zella the mother of Miss Blanche Mt. Eden. We are glad to say that Owens and a few other live Masden, primary teacher at Mrs. Miller is in perfect health teachers gave their pupils a Lebanon Junction, KY. and wish her many more happy Christmas tree Friday before the Miss Maggie Stallings and Harley birthdays. holidays and at all places a big Proctor, Miss Mollie Martin and crowd of anxious parents and ***New Shop at Salt River Robert Deavers, Miss Geneva happy children were in attendance Deagon and Clyde Harned, Miss Mr. E. W. Johnson, who for many and the good St. Nick left Mae Cundiff and Edw. Brown, all years had a shop and general store presents there for the whole of this county, were also married at Mt. Eden and who has moved community, thus again just before the holiday, while to Salt River, will soon open a encouraging community spirit and Miss Lena Ice and Curren general blacksmith and repair making our schools real life social Troutwine were married shop at that place. -

6 My Bright Abyss: Thoughts on Modern Belief 34 Why Science

EXPLORING THE INTEGRATION OF FAITH, JUSTICE, AND THE INTELLECTUAL LIFE IN JESUIT, CATHOLIC explore HIGHER EDUCATION P UBLISHED BY THE I GNATIAN C ENTER AT S ANTA C LARA U NIVERSITY SPRING 2014 VOL. 17 6 My Bright Abyss: 18 Why Is God for 34 Why Science 46 The Fragility Thoughts on Christians Good Needs God of Faith Modern Belief for Nothing? Published by the Ignatian Center for Jesuit Education at Santa Clara University SPRING 2014 EXPLORING THE INTEGRATION OF FAITH, JUSTICE, AND THE INTELLECTUAL LIFE IN JESUIT, CATHOLIC HIGHER EDUCATION Michael C. McCarthy, S.J. ’87 Executive Director Theresa Ladrigan-Whelpley Editor Elizabeth Kelley Gillogly ’93 Managing Editor Amy Kremer Gomersall ’88 Design Ignatian Center Advisory Board Margaret Taylor, Chair Katie McCormick Gerri Beasley Charles Barry Dennis McShane, M.D. Patti Boitano Russell Murphy Jim Burns Mary Nally Ternan Simon Chin Saasha Orsi 4 Dialogue and Depth: Nicole Clawson William Rewak, S.J. Michael Engh, S.J. Exploring What Good Is God? Jason Rodriguez Frederick Ferrer Richard Saso Introduction to Spring 2014 explore Javier Gonzalez Robert Scholla, S.J. Michael Hack BY THERESA LADRIGAN-WHELPLEY Gary Serda Catherine Horan-Walker Catherine Wolff Tom Kelly Michael Zampelli, S.J. Michael McCarthy, S.J. 6 My Bright Abyss: Thoughts on Modern Belief explore is published once per year by the Ignatian Center for Jesuit Education at Santa Clara University, BY CHRISTIAN WIMAN 500 El Camino Real, Santa Clara, CA 95053-0454. 408-554-6917 (tel) 408-551-7175 (fax) www.scu.edu/ignatiancenter 10 On Modern Faith: “Out of the The views expressed in explore do not necessarily represent the views of the Ignatian Center. -

Albert Abrams, MD

The King of Quacks: Albert Abrams, M.D. One of the greatest quacks of all time was Albert Abrams, M.D. Abrams earned the dubious distinction of "the dean of twentieth century charlatans" by the American Medical Association. J.D. HAINES, M.D. he physician is the most convincing of all quacks. He has both the knowledge and the authority to pro- Tmote his claims, no matter how outlandish. In the history of physician-quacks, the undisputed king is Dr. Albert Abrams. This Stanford professor was given the dubi- ous distinction as the "dean of twentieth century charla- tans," according to the American Medical Association in 1924 (Cramp 1936). Quack is short for quacksalver, which means one who "quacks," or makes a loud noise, about a remedy, such as a salve (Randi 1995). The requirements for a convincing quack are threefold. First, he must pretend to have knowl- edge of some remarkable medical remedy. Second, he must SKEPTICAL INQUIRER May/June 2002 45 be a convincing liar. And finally, he must have a gullible vic- (Splanchnic Neurasthenia) in 1904, Diseases of the Lungs in tim. As Benjamin Franklin once said, "There are no greater 1905, and Man and His Poisons in 1906. liars in the world than quacks—except for their patients" In The Blues, he set forth his theory that neurasthenia (sim- (Randi 1995). ilar to nervous exhaustion) resulted in part from stagnation of Even though history has revealed multitudes of charlatans, the blood in the abdominal veins. Treatment consisted of phys- their victims often remain their most ardent supporters. -

Americana Bibliographies Books in All Fields

Sale 490 Thursday, October 11, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Literature - Americana Bibliographies Books in All Fields Auction Preview Tuesday, October 9, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, October 10, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, October 11, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Mary Austin, "The High Priestess of Regional Literature": a Review Essay

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 55 Number 4 Article 6 10-1-1980 Mary Austin, "The High Priestess of Regional Literature": A Review Essay Necah Stewart Furman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Furman, Necah Stewart. "Mary Austin, "The High Priestess of Regional Literature": A Review Essay." New Mexico Historical Review 55, 4 (2021). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol55/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. MARY A US TIN, "THE HIGH PRIESTESS OF REGIONAL LITERATURE": A REVIEW ESSAY NECAHSTEWARTFURMAN LITERARY AMERICA 1903-1934: THE MARY AUSTIN LETTERS. Edited by T. M. Pearce. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1979. Pp. xv, 296. Illus., appen dix, index. $17.95. ROOM AND TiME ENOUGH: THE LAND OF MARY AUSTIN. Lines by Mary Austin. Edited and Introduction by Augusta Fink. Photographs by Morley Baer. Flagstaff, Ariz.: Northland Press, 1979. Pp. vi, 75. Illus. $20.00. RECENT PUBLICATIONS INDICATE a resurgence of interest in the life and works of Mary Hunter Austin. The person most responsible for this revival is T. M. Pearce, who has contributed the largest share to the collection of writings about Mary Austin with publication of his Beloved House in 1940, Mary Hunter Austin in 1970, and with Literary America 1903-1934: The Mary Austin Letters in 1979. While Pearce's previous studies have been largely biographical in nature, Literary America helps to place Austin in perspective among her peers as one of the most highly-respected writers of the first three decades of the twentieth cen tury.