Entire Issue Volume 32, Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

Sons of Confederate Veterans Awards and Insignia Guide 2013 National

Sons of Confederate Veterans Awards and Insignia Guide 2013 National Awards and Officer Insignia Amended by GEC 2012 All previous editions are obsolete. Foreword This booklet has been developed to assist members in becoming familiar with and understanding eligibility for all national awards and officers insignias of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. It includes all awards approved by the General Executive Council through the March 2011. Several awards have been dropped and several new awards have been approved. A new format for the booklet has been chosen to make it easier for concerned individuals to determine the exact criteria, method of selection and presentation for each award. An electronic copy of this booklet will also be kept on the SCV web site at www.scv.org. 1 Table of Contents Award Dates to Remember .............................................................................................................................4 Order of Presentation of Awards ....................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Our Highest Honors .......................................................................................................................6 Confederate Medal of Honor ......................................................................................................................6 Roll of Honor Medal ....................................................................................................................................7 Jefferson -

Confederate Burials in the National Cemetery

CONFEDERATE BURIALS IN THE NATIONAL CEMETERY The Monument Toward Reconciliation The Commission for Marking Graves of Confederate Dead On May 30, 1868, the Grand Army of the Republic decorated began documenting burials in July 1906. No one was able Union and Confederate graves at Arlington National Cemetery. to explain to the Commission how the UDC arrived at the Thirty years later President William McKinley proclaimed: number of 224 unknown listed on the tablet. Few records The Union is once more the common altar of our love and accompanied the burials moved from Rural Cemetery, which loyalty, our devotion and sacrifce . Every soldier’s grave had the greatest number of Confederate burials in the area. made during our unfortunate Civil War is a tribute to American Many records were incomplete and documentation of remains valor . in the spirit of fraternity we should share with you in removed to other states was contradictory. The Commission Citizens Volunteer Hospital in Philadelphia was one of many facilities where Confederate the care of the graves of the Confederate soldiers. prisoners captured at Gettysburg were treated, c. 1865. Library of Congress. agreed that graves could not be matched with individuals. The War Department created the Confederate section at Arlington in 1901, and marked the graves with The Confederate Section distinctive pointed-top marble headstones. Five years All of the Confederate prisoners of war buried here died in a later, Congress created the Commission for Marking Civil War military hospital in or near Philadelphia. All were Graves of Confederate Dead to identify and mark the originally interred near the hospital where they died. -

The Mississippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists Volume 22 | Number 1 Article 5 January 2004 "The iM ssissippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History Lisa Speer Southeast Missouri State University Heather Mitchell State University of New York Albany Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/provenance Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Speer, Lisa and Mitchell, Heather, ""The iM ssissippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History," Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists 22 no. 1 (2004) . Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/provenance/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 51 "The Mississippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History Lisa Speer and Heather Mitchell · The establishment of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) was a cultural milestone for a state that some regarded as backward in the latter decades of the twenti eth century. Alabama and Mississippi emerged as pioneers in the founding of state archives in 1901 and 1902 respectively, representing a growing awareness of the importance of pre serving historical records. American historians trained in Ger many had recently introduced the United States to the applica tion of scientific method to history. -

Patriots Periodical Volume 1, Number 4

Vol. 1, No. 4 Copyright 2014 October 2014 COMMANDER’S CORNER protests occurring in the Midwest with hundreds by Eddie “Spook” Pricer upon hundreds of protesters received all sorts of media coverage. A numerical advantage depicts This month’s Commander’s Corner strength, whether real or imagined. Watch the deals with the definition of strength elected and appointed national figures. When do and its importance to the Sons of Confederate they take action? They react when the public cries Veterans. Before I start, though, I want to thank out in large numbers or when they think that outcry those that are utilizing our Web Site and researching will be forthcoming. Unfortunately, in today’s and submitting articles for the Patriots Periodical modern era it is all too often numbers that matter, Newsletter. It is great to have the Associate Editor not substance. telling you that we may have to carry some articles or portions of articles over into upcoming issues in The capacity for exertion or endurance can also be an effort to keep our newsletter a reasonable and expressed through numbers as well as other enjoyable size. Thanks to everyone and keep the avenues. If you examine a 5 gallon bucket and a articles coming. 10,000 gallon tank filled with water, which one will benefit your garden the most? If you match a four Strength person track relay team against a single runner in a 15,000 meter race, which will win and how soon Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary describes will they be able to race again? Being physically fit strength as (1) the quality or state of being strong, is key, but when you increase the number, you (2) the capacity for exertion or endurance, (3) the increase the ability for exertion and endurance. -

Whitewashing Or Amnesia: a Study of the Construction

WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES A DISSERTATION IN Sociology and History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by DEBRA KAY TAYLOR M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2005 B.L.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2000 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 DEBRA KAY TAYLOR ALL RIGHTS RESERVE WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES Debra Kay Taylor, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT This inter-disciplinary dissertation utilizes sociological and historical research methods for a critical comparative analysis of the material culture as reproduced through murals and monuments located in two counties in Missouri, Bates County and Cass County. Employing Critical Race Theory as the theoretical framework, each counties’ analysis results are examined. The concepts of race, systemic racism, White privilege and interest-convergence are used to assess both counties continuance of sustaining a racially imbalanced historical narrative. I posit that the construction of history of Bates County and Cass County continues to influence and reinforces systemic racism in the local narrative. Keywords: critical race theory, race, racism, social construction of reality, white privilege, normality, interest-convergence iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, have examined a dissertation titled, “Whitewashing or Amnesia: A Study of the Construction of Race in Two Midwestern Counties,” presented by Debra Kay Taylor, candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

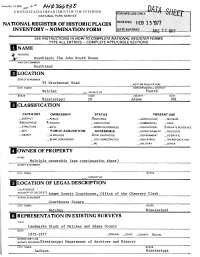

Hclassification

Form No 10-300 ^ \Q-1^ f*H $ *3(0(0 ?3 % UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Routhland; The John Routh House AND/OR COMMON Routhland 92 Winchester Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Natchez _. VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Adams 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) ?_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple ownership (see continuation sheet) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Adams County Courthouse, Office of the Chancery Clerk STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Square CITY. TOWN STATE Natchez Mississippi REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Landmarks Study of Natchez and Adams County DATE 1972-1977 —FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY J?LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY, TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi j DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .^EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE____ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Routhland is located in the old suburbs lying just southeast of the original town of Natchez. The house occupies the summit of a high but gently-rounded hill in a large landscaped park. -

Viewing Guide

VIEWING GUIDE RAPPAHANNOCK COUNTY Harrison Opera House, Norfolk What’s Inside: VAF Sponsors 2 Historical Sources 8 About the Piece 3 Civil War Era Medicine 9 The Voices You Will Hear 4 Real Life Civil War Spies 10 What is Secession? 5 What is Contraband? 11 Topogs 6 Music During the Civil War 12-13 Manassas 7 Now That You’ve Seen Rappahannock County 14 vafest.org VAF SPONSORS 2 The 2011 World Premiere of Rappahannock County in the Virginia Arts Festival was generously supported by Presenting Sponsors Sponsored By Media Sponsors AM850 WTAR Co-commissioned by the Virginia Arts Festival, Virginia Opera, the Modlin Center for the Arts at the University of Richmond, and Texas Performing Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. This project supported in part by Virginia Tourism Corporation’s American Civil War Sesquicentennial Tourism Marketing Program. www.VirginiaCivilWar.org VIRGINIA ARTS FESTIVAL // RAPPAHANNOCK COUNTY ABOUT THE PIECE 3 RAPPAHANNOCK COUNTY A new music theater piece about life during the Civil War. Ricky Ian Gordon Mark Campbell Kevin Newbury Rob Fisher Composer Librettist Director Music Director This moving new music theater work was co- Performed by five singers playing more than 30 commissioned by the Virginia Arts Festival roles, the 23 songs that comprise Rappahannock th to commemorate the 150 anniversary of the County approach its subject from various start of the Civil War. Its creators, renowned perspectives to present the sociological, political, composer Ricky Ian Gordon (creator of the and personal impact the war had on the state of Obie Award-winning Orpheus & Euridice and Virginia. -

Jacob Nicholls Clark - Revolutionary War Soldier by Wilma J

Jacob Nicholls Clark - Revolutionary War Soldier By Wilma J. Clark of Deltona, Florida Jacob Nicholls Clark, born 13 October 1754, followed his brother James Clark into military service in the Revolutionary War in January of 1776. James had enlisted from Baltimore, Maryland in 1775. Jacob enlisted under Captain Samuel Smith in the First Regiment of the Maryland Line, in Baltimore Maryland, which was commanded by Colonel William Smallwood.1 Jacob’s Regiment marched from Baltimore, through Pennsylvania and New Jersey to the American Army Headquarters in New York City. 27 August 1776 he fought in the Battle of Long Island, which was commanded by Lord Sterling, and then retreated with the troops to Fort Washington, York Island, New York. The British and Hessians attacked Fort Washington 16 November 1776, overpowering the American Army, and forcing a surrender of Fort Washington to the Hessians. Jacob and other surviving American soldiers fled across the Hudson River to Fort Lee, New Jersey, only to find that Fort Lee had also been captured 20 November 1776. After these defeats, the Continental Army was exhausted, demoralized and uncertain of its future. It was a cold winter and many of the soldiers were now walking barefoot in the snow, leaving trails of blood. Believing that the need to raise the hopes and spirits of the troops and people was imperative, General George Washington, Commander in Chief, ordered a massive surprise attack on the Hessian held city of Trenton, New Jersey. Colonel Smallwood’s First Maryland Regiment marched into the Battle of Trenton under the command of Major General Nathaniel Greene, 26 December 1776,2 and Jacob was once again engaged in battle. -

To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look for Assistance:” Confederate Welfare in Mississippi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 "To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi Lisa Carol Foster University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Foster, Lisa Carol, ""To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi" (2017). Master's Theses. 310. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/310 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster August 2017 Approved by: _________________________________________ Dr. Susannah Ural, Committee Chair Professor, History _________________________________________ Dr. Chester Morgan, Committee -

Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Articles Faculty Publications 1-2004 "The Mississippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History Lisa K. Speer Heather Mitchell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles Part of the Public History Commons "The Mississippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History Lisa Speer and Heather Mitchell The establishment of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) was a cultural milestone for a state that some regarded as backward in the latter decades of the twenti eth century. Alabama and Mississippi emerged as pioneers in the founding of state archives in 1901 and 1902 respectively, representing a growing awareness of the importance of pre serving historical records. American historians trained in Ger many had recently introduced the United States to the applica tion of scientific method to history. The method involved care ful inspection of primary documents and writings to produce objective answers to large historical questions.' The challenges involved in ferreting out primary docu ments, however, often frustrated the research efforts of histo rians. Some states, like Massachusetts, had well-established historical societies that functionedas primary source reposito ries. In other states individuals held historical records in pri vate libraries, and public records were scattered among the ' Peter Novick, The Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 37-40. PROVENANCE, vol. XXII, 2004 PROVENANCE 2004 _ c:reating agencies.2 In the 1880s the American Historical =�-iau:·on (AHA) sponsored the first organized national ef . -

On the Imperishable Face of Granite: Civil War Monuments and the Evolution of Historical Memory in East Tennessee 1878-1931

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2011 On the Imperishable Face of Granite: Civil War Monuments and the Evolution of Historical Memory in East Tennessee 1878-1931. Kelli Brooke Nelson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, Kelli Brooke, "On the Imperishable Face of Granite: Civil War Monuments and the Evolution of Historical Memory in East Tennessee 1878-1931." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1389. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1389 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “On the Imperishable Face of Granite”: Civil War Monuments and the Evolution of Historical Memory in East Tennessee, 1878-1931, _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _____________________ by Kelli B. Nelson December 2011 _____________________ Dr. Steven E. Nash, Chair Dr. Andrew L. Slap Dr. Stephen G. Fritz Dr. Tom D. Lee Civil War, East Tennessee, memory, monuments ABSTRACT “On the Imperishable Face of Granite”: Civil War Monuments and the Evolution of Historical Memory in East Tennessee, 1878-1931 by Kelli B.