Torres Strait Bepotaim: an Overview of Archaeological and Ethnoarchaeological Investigations and Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

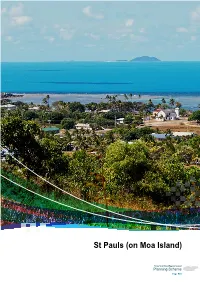

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

How Torres Strait Islanders Shaped Australia's Border

11 ‘ESSENTIALLY SEA‑GOING PEOPLE’1 How Torres Strait Islanders shaped Australia’s border Tim Rowse As an Opposition member of parliament in the 1950s and 1960s, Gough Whitlam took a keen interest in Australia’s responsibilities, under the United Nations’ mandate, to develop the Territory of Papua New Guinea until it became a self-determining nation. In a chapter titled ‘International Affairs’, Whitlam proudly recalled his government’s steps towards Papua New Guinea’s independence (declared and recognised on 16 September 1975).2 However, Australia’s relationship with Papua New Guinea in the 1970s could also have been discussed by Whitlam under the heading ‘Indigenous Affairs’ because from 1973 Torres Strait Islanders demanded (and were accorded) a voice in designing the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Whitlam’s framing of the border issue as ‘international’, to the neglect of its domestic Indigenous dimension, is an instance of history being written in what Tracey Banivanua- Mar has called an ‘imperial’ mode. Historians, she argues, should ask to what extent decolonisation was merely an ‘imperial’ project: did ‘decolonisation’ not also enable the mobilisation of Indigenous ‘peoples’ to become self-determining in their relationships with other Indigenous 1 H. C. Coombs to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), 11 April 1973, cited in Dexter, Pandora’s Box, 355. 2 Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 4, 10, 26, 72, 115, 154, 738. 247 INDIGENOUS SELF-determinatiON IN AUSTRALIA peoples?3 This is what the Torres Strait Islanders did when they asserted their political interests during the negotiation of the Australia–Papua New Guinea border, though you will not learn this from Whitlam’s ‘imperial’ account. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Card Operated Meter Information

Purchasing a power card for your card-operated meter Power cards are available from the following sales outlets: Community Retail Agent Address Arkai (Kubin) Community T.S.I.R.C. - Kubin KUBIN COMMUNITY, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Arkai (Kubin) Community CEQ - Kubin IKILGAU YABY RD, KUBIN VILLAGE, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Aurukun Island & Cape 39 KANG KANG RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Aurukun Supermarket Aurukun Kang Kang Café 502 KANG KAND RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Badu Hotel 199 NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Island & Cape Badu MAIRU ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Supermarket (Bottom Shop) Badu (Mulgrave) Island J & J Supermarket 341 CHAPMAN ST, BADU ISLAND QLD (Top Shop) 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Badu NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Bamaga Bamaga BP Service AIRPORT RD, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Station Bamaga Cape York Traders 201 LUI ST, BAMAGA QLD 4876 – Bamaga Store Bamaga CEQ – Bamaga 105 ADIDI AT, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island CEQ – Boigu TOBY ST, BOIGU QLD 4875 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Boigu 66 CHAMBERS ST, BOIGU ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) Daido Tavern PILOT ST, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) T.S.I.R.C. - Darnley COUNCIL OFFICE, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Dauan Island (Mt CEQ - Dauan MAIN ST, DAUAN ISLAND QLD 4875 Cornwallis) Supermarket Dauan Island (Mt T.S.I.R.C. - Dauan COUNCIL OFFICE, MAIN ST, DAUAN Cornwallis) ISLAND QLD 4875 Doomadgee CEQ – Doomadgee 266 GUNNALUNJA DR, DOOMADGEE QLD Supermarket 4830 Doomadgee Doomadgee 1 GOODEEDAWA RD, DOOMADGEE -

7. Locating Seven Rivers

7. Locating Seven Rivers Fiona Powell 1. Introduction In December 1890, while on patrol down the west coast of northern Cape York Peninsula (NCYP), accompanied by Senior-Constable Conroy and a few native troopers of the Thursday Island Water Police, Sub-Inspector Charles Savage visited ‘the Seven Rivers’.1 From this place, the party went south to the mouth of the Batavia (now Wenlock) River. There they met the chief or mamoose of the Seven Rivers tribe,2 a man identified as Tongambulo (variations Tong-ham-blow,3 Tongamblow4 and Tong-am-bulo5) and also known as Charlie in one account.6 At the time of this meeting, Sub-Inspector Savage was seeking another candidate for induction into government policies intended ‘to civilize the Natives of Cape York Peninsula’.7 The first NCYP Aboriginal person to have had this experience was Harry, also known as King Yarra-ham-quee, and described as the ‘mamoose of the Jardine River’.8 This man had been taken to Thursday Island earlier in the year: where he underwent a course of instruction and when he had sufficiently understood what was required of him was taken back and made king, his subjects and several visitors, Natives of Prince of Wales Island, being present.9 1 ‘Conciliating the Natives’, Torres Straits Pilot, 6 December 1890, and published in The Queenslander, Saturday 27 December 1890: 1216 [hereafter ‘Conciliating the Natives’ Torres Straits Pilot]. 2 Savage, Charles 1891, Letter to the Honourable John Douglas, Government Resident Thursday Island, dated 11 February 1891, Queensland State Archives, Item D 143032, File - Reserve. -

Part 7 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Sea Transport Safety The marine investigation unit of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) was contacted for information pertaining to recent accidents and incidents with large trading vessels in the region. The data provided related to five incidents that occurred after July 1995 and before 2004: a) A man overboard from the vessel Murshidabad in 1996; b) A close quarters situation between the Maersk Taupo and a small dive runabout off Ackers Shoal Beacon in 1997; c) The grounding of the vessel Thebes on Larpent Bank in 1997; d) The grounding of the vessel Dakshineshwar on Larpent Bank in 1997; and e) The grounding of the vessel NOL Amber on Larpent Bank in 1997. Figure 3.7 shows the location of marine accidents that have occurred in northern Queensland in 2004. Figure 3.7 Location of Marine Accidents in Northern Queensland (2004) Source: MSQ: 2005 Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 21 Figure 3.8 Existing Ferry Services Torres Strait Transport Ugar (Stephen) Island Infrastructure Plan Papua New Guinea Ferry Routes ° Saibai (Kaumag) Island Dauan Island Erub (Darnley) Island Map 1 - Saibai (Kaumag) Island to Dauan Island 1:200,000 Map 2 - Ugar (Stephen) Island to Erub (Darnley) Island 1:150,000 Hammond Waiben Map 1 Island (Thursday) Island Map 2 Nguruppai (Horn) Island Muralug (Prince of Wales) Island Map 3 Seisia Seisia Map 3 - Thursday Island 1:300,000 -

Week16 E-Record .Indd

PINEAPPLE HOTEL CUP E-FOOTY RECORD ROUND 16 E-Footy RECORD 2nd August 2008 Issue 16 Editorial with Marty King GET INTO THE SPIRIT OF KICK AROUND AUSTRALIA DAY Next Thursday, 7th August, is the 150th anniversary of the fi rst recorded match of Australian Football between Melbourne schools Scotch College and Melbourne Grammar at Richmond Paddock, at what is now Yarra Park next to the MCG. As part of the celebrations of this wonderful occasion the AFL is staging ‘Kick Around Australia Day’ and I hope footy fans throughout Queensland will join the party. It’s an opportunity for all Australians to come together through football, and to wear your team colours or club scarf and have a kick of the famous Sherrin. There will be a stack of celebrations right across the country, but please, wherever you are and whatever you are doing, be part of it. Introduce friends, workmates and school friends to AFL and all that makes it the No.1 sport in Australia. Schools around the country have been busy making preparations for the day, with thousands of kids set to take part in football themed lessons, designed in line with the curriculum. Businesses and community organizations, too, are encouraged to get into the spirit and help recognize football’s 150th birthday, which is part of the Tom Wills Round, dedicated to one of the founding forefathers of our game. For further information on this and other 150th year celebrations, visit www.150years.com.au AND CONGRATULATIONS TO THE QUEENSLAND COUNTRY SIDE Special congratulations to the Queensland Country side which won the division two title at last week’s Australian Country Championships in Shepparton, Victoria. -

1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY 1997~1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2 ©Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISSN 1324–163X This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. Annual Report 1997~98 PUPUA NEW GUINEA SAIBAI ISLAND (Kaumag Is) BOIGU ISLAND UGAR (STEPHEN) ISLAND DAUAN ISLAND TORRES STRAIT DARNLEY ISLAND YAM ISLAND MASIG (YORKE) ISLAND MABUIAG ISLAND MER (MURRAY) ISLAND BADU ISLAND PORUMA (COCONUT) ISLAND ST PAULS WARRABER (SUE) ISLAND KUBIN MOA ISLAND HAMMOND ISLAND THURSDAY ISLAND (Port Kennedy, Tamwoy) HORN ISLAND PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND SEISIA BAMAGA CAPE YORK TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY Senator the Hon. John Herron Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Suite MF44 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister In accordance with section 144ZB of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989, I am delighted to present you with the fourth Annual Report of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). -

The Enigma of Moent

March, 2005 ������������������������������������������������������� The Enigma of Moent he first recorded introduced toponyms on the Australian continent were bestowed by Willem Janszoon (more commonly known as Jansz) in 1606 along the north-west Tcoast and tip of Cape York Peninsula. Jansz was sent out from Banda in the Duyfken by the V.O.C. (Dutch East India Company) to extend their knowledge of “the great land of Nova Guinea and other East- and Southlands” and to look for potential markets for trade. Unfortunately his log is no longer extant and the only verification we have of this voyage are two diary entries, some V.O.C. correspondence, and some cartographic evidence in the form of an anonymous copy (circa 1670) of Jansz’s original chart (Schilder 1976:43-44) (see Fig. 1).1 The Duyfken chart is held in the National Library of Austria in Vienna; however, a copy of it may also be found in the Mitchell Library, NSW. Its legend states: “This chart shows the route taken by the pinnace Duifien on the outward as well as on the return voyage when she visited the countries east of Banda up to New Guinea […]”. Jansz’s course is very clearly marked, and shows where he made the first recorded European landfall on the Australian continent at R[ivier] met het Bosch (River with Bush). It is a remarkable coincidence that Australia’s first recorded European toponym should contain the word bush, a term which now has such a distinct Australian meaning and forms such an important facet of the Australian psyche. -

Stone on Stone : Story of Hammond Island Mission

STONE ON STONE Story of Hammond Island Mission * compiled by B D312.37 Tyrone C. Deere S1 Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007, B D312.37/S1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library Published by Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church, Thursday Island Qld 4875 Printed by Hillside Securities Pty. Ltd. (A.C.N. 056 773 721) Trading as TORRES NEWS. Thursday Island Queensland 4875 © Tyrone Cornelius Deere August 1994 All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Cover: St. Joseph's Church Hammond Island. Standing on top of the hill it can be seen from Thursday Island, and by those people travelling the waters of the Strait. Deere. Tyrone Cornelius 01.01.1912 Stone on Stone Building Stone Church - Hammond Is. Qld - History letters Hammond Island Mission - General Interest ISBN 86420 028 6 Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007, B D312.37/S1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library INTRODUCTION "Stone on Stone" began as the simple reprinting of the story of the building of St. Joseph's Church, Hammond Island as told by the builder Fr. Tom Dixon, and Fr. Paul Power an assistant priest, to the editor of "Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Annals" and printed there in 1953-1954. -

Northern Mix Featuring Torres Strait Artists Billy Missi, Ben Hodges & Glen Mackie

Copyright © Billy Missi 2009 Northern Mix featuring Torres Strait artists Billy Missi, Ben Hodges & Glen Mackie 14th August ~ 3rd October 2009 NORTHERN MIX Woolloongabba Art Gallery is proud to present a selection BEN HODGES of artists from the Torres Strait Islands. Billy Missi is I have developed my art and design practice over the past featured with two emerging artists from the region, decade and I am acknowledged in my community as an Ben Hodges and Glen Mackie. This show aims to emerging artist who is versatile across a range of mediums highlight the rich cultural history of Queensland’s which I use to explore my beliefs, cultural heritage and most northern islands. links to the natural environment. Growing up in mainly in the city, I possess a rich balance of cultural and urban BILLY MISSI influences and have been able to express this through Billy Missi comes from ‘Maluilgal’ country in ‘Zenadth Kes’ the use of traditional motifs together with contemporary (Western Torres Strait). He is apart of Wagedagam Tribe materials, technologies and imagery. The salt water air of with major totem of Kodal (crocodile) and an associate my culture passes through my lungs and the bloodlines of member to Dhanghal (dugong) clan of Panai to the East my descendants run through my veins yet I restrict myself and ‘Kaigas’ (shovel nose ray) clan of Geomu to the south from painting traditional stories. I tell my stories from on the Island of ‘Mabuiag’. my individual experiences, struggles and triumphs as a son, grandson, brother, father, uncle, living in the urban Billy has grown up in the traditional customary ways surroundings of mainstream society. -

(2005) Indigenous Subsistence Fishing at Injinoo Aboriginal Community, Northern Cape York Peninsula

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Phelan, Michael John (2005) Indigenous subsistence fishing at Injinoo Aboriginal Community, northern Cape York Peninsula. Masters (Research) thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/1281/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/1281/ INDIGENOUS SUBSISTENCE FISHING AT INJINOO ABORIGINAL COMMUNITY, NORTHERN CAPE YORK PENINSULA Thesis submitted by Michael John PHELAN BSc Qld in December 2005 for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Tropical Environment Studies and Geography, James Cook University INDIGENOUS SUBSISTENCE FISHING AT INJINOO ABORIGINAL COMMUNITY, NORTHERN CAPE YORK PENINSULA "This is a story of how Aboriginal hunt for dugong in the early days. The markings tell of how dugong feed and bear their young offspring." Artist: Roy Solomen, Injinoo Aboriginal Community STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses Network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. Or I wish this work to be embargoed until: Or I wish the following restrictions to be placed on this work: ___21/06/06_________________________ Signature Date II STATEMENT OF SOURCES I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education.