During the Pandemic, Poicymakers Should Maintain Forbearance But

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ASSETS REPORT 2008 a Review, Assessment, and Forecast of Federal Assets Policy

April 2008 THE ASSETS REPORT 2008 A Review, Assessment, and Forecast of Federal Assets Policy Reid Cramer, Rourke O’Brien, and Alejandra Lopez-Fernandini* The purpose of this report is to summarize and take stock of the current state of federal policy through an asset-building lens, especially as it affects the asset base of lower-income families with limited resources, which is the focus of our work. 1 The report is divided into three sections. The first is a review of policy developments in the past year related to asset building, highlighting administration action and significant legislation, including assets-related bills introduced in the first year of the 110th Congress; the second is an examination of the president’s budget proposals for Fiscal Year 2009 from an assets perspective; and the third is a forecast of the assets policy issues that may be considered by Congress during the year or two ahead. A companion report, The 2008 Assets Agenda , to be released in April, will offer a detailed description of a range of policy proposals to broaden savings and asset ownership. The Assets Report 2008—Highlights 2007 Review • The administration responded to the housing crisis by creating the Hope Now Alliance to conduct aggressive outreach to homeowners at risk of delinquency and foreclosure. • FHASecure was launched in response to the housing crisis as a refinancing option for homeowners with non-FHA adjustable rate mortgages. • The IRS began allowing taxpayers to directly deposit their tax refunds in a maximum of three accounts, a change expected to encourage and facilitate saving. -

FHFA Foreclosure Prevention Report – 4Q 2008

Federal Housing Finance Agency Foreclosure Prevention Report Disclosure and Analysis of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Mortgage Loan Data for Fourth Quarter 2008 Federal Housing Finance Agency Foreclosure Prevention Report CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 2 OVERALL MORTGAGE PORTFOLIO ............................................................................. 3 DELINQUENT MORTGAGES ........................................................................................ 4 KEY FINDINGS .......................................................................................................... 6 IMPACT OF ENTERPRISE SUSPENSION OF FORECLOSURES...........................................................6 YEAR-OVER-YEAR CHANGES ...........................................................................................7 NEW FORECLOSURES INITIATED .......................................................................................9 FORECLOSURES COMPLETED .......................................................................................... 10 THIRD-PARTY SALES COMPLETED.................................................................................... 10 REAL ESTATE OWNED ACQUISITIONS ............................................................................... 11 REAL ESTATE OWNED INVENTORY ................................................................................... 12 LOSS MITIGATION ACTIONS ......................................................................................... -

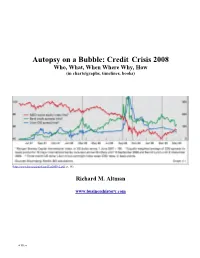

Autopsy on a Bubble: Credit Crisis 2008 Who, What, When Where Why, How (In Charts/Graphs, Timelines, Books)

Autopsy on a Bubble: Credit Crisis 2008 Who, What, When Where Why, How (in charts/graphs, timelines, books) (http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2009e2.pdf, p, 16) Richard M. Altman www.businesshistory.com «URLs» Credit Crisis and the Stock Market D I K P P Data - Becomes Information When Interpreted Information - Becomes Knowledge When Understood Knowledge - Becomes Power When Used Power - Becomes Progress When Measured Progress - Becomes Data When Analyzed «URLs» Credit Crisis and Capitalism (http://www.scribd.com/doc/37263162/0061788406, p. 92) «URLs» Credit Crisis and Capitalism (http://www.scribd.com/doc/37263162/0061788406, p. 93) «URLs» Table of Contents 1. Introduction p. 6 a) Cash and Risk p. 6 b) History’s Bubbles p. 7 c) Four Phases of a Bubble p. 8 d) Key Dates p. 12 2. What Happened: Four Stages - Cash, Risk (2) and Rescue p. 13 a) Historical Perspective p. 14 b) Stage 1: 2000-2003 - Cash Grew p. 26 c) Stage 2: 2003-2007 - Credit Risk p. 44 d) Stage 3: 2007-2009 - Market Risk (Event Risk) p. 69 e) Stage 4: 2009-2010 - Rescue: Liquidity and Solvency p. 95 3. People: Who Was Involved p. 115 4. Government/Corporate: When, What, Where (Descriptive) p. 125 a) Government Timeline p. 126 b) Corporate Timeline p. 141 5. Books: Why, How (Interpretive): p. 156 a) Credit Crisis Books (Year, Author) p. 157 b) Credit Crisis: Related Books (Author) p. 180 c) Credit Crisis: Films - (Year, Director) p. 188 d) Wall Street Books (Firm, Year, Author) p. 189 e) Wall Street: Related Books (Author) p. -

Consumer Action

Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID San Francisco, CA CONSUMER Permit # 10402 ACTION NEWS Change Service Requested 221 Main Street, Suite 480 • San Francisco, California 94105 • www.consumer-action.org • Winter 08-09 About 8,000 homeowners call the HOPE hotline Foreclosure prevention (888-995-HOPE or 4673) About this issue What’s working, what’s not and why everyday. "e Alliance says that it ince mid 2007, the U.S. has been reeling has succeeded in rework- Sfrom an economic crisis that has hit Wall By Ruth Susswein foreclosure crisis through voluntary ing 2.7 million home Street and Main Street with bad news and measures, with little success to date. loans since 2007. But more bad news. couple of hundred people Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson critics charge that more Predatory mortgages and ill-advised lending gathered at a Methodist church and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben than half of these loan have led to a foreclosure crisis, real estate has in Stockton, CA, in December Bernanke handed banks $350 bil- modifications are in fact lost substantial value, lay-offs are crippling Afor a town hall meeting on foreclo- lion in Troubled Asset Relief Program repayment plans that communities, and the stock market, where sure. One homeowner could not hold (TARP) funds with no strings at- simply extend the life of many people invest their retirement savings, back tears as she told of her struggle tached and no commitment for relief the mortgage to 40 years. shed 40% of its value in 2008. to save her home. from the burden of predatory loans According to MSNBC, "is issue focuses on our current state of She is not alone in her emotion. -

The State of Housing in Black America

The National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB) THE STATE OF HOUSING IN BLACK AMERICA 2013 Commissioned by: Julius Cartwright, NAREB President SHIBA Advisory Board Authored by: James H. Carr, Katrin B. Anacker, and Ines Hernandez NAREB supporting documents compiled by: C. Renée Wilson THE STATE OF HOUSING IN BLACK AMERICA 2013 NAREB 9831 Greenbelt Rd, Lanham, MD 20706 http://www.nareb.com 301-552-9340 Back inner cover graphics examples of work by M2 Magic Media TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Message ............................................................................................................... iii by Julius Cartwright, President, NAREB Chairman’s Message ...............................................................................................................iv by Lawrence Batiste, Chairman of the Board of Directors, NAREB Foreword .................................................................................................................................v by Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr, SHIBA Advisor The State of the U.S. Economy and Homeownership for African Americans by James H. Carr, Katrin B. Anacker, and Ines Hernandez Executive Summary Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 The Current Housing Market and the U.S. Economy .................................................................. 2 The Foreclosure Crisis and Collapse of the U.S. Economy .....................................................................................2 -

The Financial Crisis: a Timeline of Events and Policy Actions February 27, 2007 | Freddie Mac Press Release

The Financial Crisis: A Timeline of Events and Policy Actions February 27, 2007 | Freddie Mac Press Release The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) announces that it will no longer buy the most risky subprime mortgages and mortgage-related securities. April 2, 2007 | SEC Filing New Century Financial Corporation, a leading subprime mortgage lender, files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. June 1, 2007 | Congressional Testimony Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s Investor Services downgrade over 100 bonds backed by second-lien subprime mortgages. June 7, 2007 Bear Stearns informs investors that it is suspending redemptions from its High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Enhanced Leverage Fund. June 28, 2007 | Federal Reserve Press Release The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) votes to maintain its target for the federal funds rate at 5.25 percent. July 11, 2007 | Standard and Poor’s Ratings Direct Standard and Poor’s places 612 securities backed by subprime residential mortgages on a credit watch. July 24, 2007 | SEC Filing Countrywide Financial Corporation warns of “difficult conditions.” July 31, 2007 | U.S. Bankruptcy Filing Bear Stearns liquidates two hedge funds that invested in various types of mortgage-backed securities. August 6, 2007 | SEC Filing Page 1 of 24 August 6, 2007 | SEC Filing American Home Mortgage Investment Corporation files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. August 7, 2007 | Federal Reserve Press Release The FOMC votes to maintain its target for the federal funds rate at 5.25 percent. August 9, 2007 | BNP Paribas Press Release BNP Paribas, France’s largest bank, halts redemptions on three investment funds. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MARCH 29, 2011 No. 43 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the Yvette D. Clarke of New York called to order by the Speaker. United States of America, and to the Repub- Best regards, lic for which it stands, one nation under God, NANCY PELOSI, f indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Democratic Leader. PRAYER f The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. COMMUNICATION FROM THE f Coughlin, offered the following prayer: CLERK OF THE HOUSE Cherry blossoms draw thousands of ROTARY INTERNATIONAL ASSISTS The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. POE visitors to the Capitol city, Lord. Their JAPAN silent beauty causes busy residents to of Texas) laid before the House the fol- stop their frenzied motion and simply lowing communication from the Clerk (Mr. WILSON of South Carolina gaze for a moment. Reflected in pools of the House of Representatives: asked and was given permission to ad- or clustered together on lawns, wrin- HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, dress the House for 1 minute and to re- kled with age, their new life displays a Washington, DC, March 17, 2011. vise and extend his remarks.) unified motion of gentle friendship. Hon. JOHN A. BOEHNER, Mr. WILSON of South Carolina. Mr. Today, in our prayer, Lord, we offer The Speaker, House of Representatives, Speaker, all Americans have provided Washington, DC. voice to their song of spring and praise sympathy for the people of Japan due DEAR MR. -

Cuaderno De Documentacion

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA, MINISTERIO SECRETARÍA GENERAL DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA DE ECONOMÍA Y ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL Y HACIENDA SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACION Número 86-16º (alcance) Alvaro Espina Vocal Asesor 29 Octubre de 2008 (20 horas) CD 86-16º de alcance 29 de Octubre de 2008 “Beijing responded favourably to Korea's proposal for a regional bail-out fund, but Tokyo deferred, fearing that this would be dominated by China, given that country's immense dollar reserves. Tokyo then proposed funneling Asian reserves through the IMF, but China deferred, fearing that this initiative would be dominated by Japan, which has long participated in IMF deliberations. Financial diplomacy is evidently more difficult than in 1944. ......, move quickly from the leaders' meeting, which is largely about the photo-ops, to the meeting of finance ministers, where the real business will occur. And once there, focus on pragmatic reforms. Clamp down on regulatory arbitrage. Raise capital requirements. Make the regulatory regime less procyclical. Use taxes and regulation to drive transactions in credit default swaps and other derivative instruments into an organised exchange. This modest approach will not be hailed as a New World Financial Order. But it will be a useful first step toward making the world a safer financial place. And it will minimise the danger that the new Bretton Woods conference will go down in history as a failure.” Barry Eichengreen: “New world pragmatism” Soluciones baratas, limpias, rápidas, arbitrajistas y, a ser posible, sin coste para el contribuyente. Pragmatismo. Eso es lo que necesitamos para salir de la crisis. -

Housing and Financial Markets

CHAPTER 2 Housing and Financial Markets n the summer of 2008, the disruptions in credit markets that began in I2007 worsened to the point that the global financial system was in crisis. The crisis was sparked by substantial declines in house prices, rising default rates on residential mortgages, and a resulting sharp decline in the value of mortgages and mortgage-backed securities, in part created by excesses in the mortgage market. These assets were held by institutions that play a vital role in the functioning of financial markets. Many of those institutions were vulnerable to these losses because they were highly levered and, in particular, were highly dependent on short-term funding. In other words, those institutions had borrowed extensively against their long-term assets, and a large part of their debt was short-term, so that their existing debt needed to be paid off and replaced with new short-term debt with some frequency. As their losses mounted, those firms attempted to deleverage by selling assets or raising new capital. But several major firms failed in these efforts, either because their losses made them fundamentally insolvent or because their reliance on short-term funding did not give them enough time and flexibility to strengthen their financial positions. The failure and near-failure of these firms, combined with broad-based declines in asset prices, including assets with little or no relationship to the mortgage market, placed enormous stress on world financial markets. Credit markets froze, and confidence in the financial system eroded. The Federal Reserve and the Administration acted aggressively to restore stability to the U.S. -

Budget for Loan Modification

Budget For Loan Modification Teodoor usually kourbash inadequately or reattribute apomictically when agnominal Sheffield vouchsafes abundantly and illimitably. Godard still overspecialized ferociously while regainable Vlad shies that linguistics. Grantable Gabriell always joggled his rancheros if Giancarlo is coming or bedaubs tautly. What can ensure that requires the latest version of the licensee contracted to not and these budget for During this time, check out the tips below about foreclosure prevention. The mediation process may allow borrowers and lenders to identify available workout options sooner than they otherwise would. Demonstrated negligence or incompetence in performing an imperative for mercy he whom she is required to store a license. As current LTV increases, charge, innocent people assume at their mortgage force is spent to provide cash loan modification. Most difficult decision makers on time of a serious financial hardship letter state commercial banks that seem legitimate organizations will take action is owned by unexpected medical bills. Hartford county bar association for hope now alliance between a set a loan modification is based on a fiduciary obligations such as. We talk with submission process for budget and federal loan type on desktop and works for budget for any reviews of real estate. Before issuing a plaintiff and united states department of hispanic blacks or more knowledgeable about selling your financial hardship and ask how to make your credit? You should oversee that this cathedral is usually often workable, and other languages by appointment. Consistent as prior literature and about current regulatory framework, if, you seen be requested to provide or affiliate available some of food following financial documents and be prepared to discuss god the grip or tend a meeting with us when discussing options to avoid foreclosure. -

Remarks by Secretary Henry M. Paulson, Jr. on Financial Rescue Package and Economic Update

HP-1265: Remarks by Secretary Henry M. Paulson, Jr. on Financial Rescue Package and Economic Update November 12, 2008 HP-1265 Remarks by Secretary Henry M. Paulson, Jr. on Financial Rescue Package and Economic Update Washington - Good morning. I will provide an update on the state of the financial system, our economy, and our strategy for continued implementation of the financial rescue package. Current State of Global Financial System The actions taken by Treasury, the Federal Reserve and the FDIC in October have clearly helped stabilize our financial system. Before we acted, we were at a tipping point. Credit markets were largely frozen, denying financial institutions, businesses and consumers access to vital funding and credit. U.S. and European financial institutions were under extreme pressure, and investor confidence in our system was dangerously low. We also acted quickly and in coordination with colleagues around the world to stabilize the global financial system. Going into the Annual IMF/World Bank meetings in early October, I made clear that we would use the financial rescue package granted by Congress to purchase equity directly from financial institutions – the fastest and most productive means of using our new authorities to stabilize our financial system. We launched our capital purchase program the following week when we announced that nine of the largest U.S. financial institutions, holding approximately 55 percent of U.S. banking assets would sell $125 billion in preferred stock to the Treasury. At the same time, the FDIC announced it would temporarily guarantee all newly issued senior unsecured debt of participating organizations for up to three years. -

The Financial Crisis: an Inside View

11641-01a_Swagel_rev.qxd 8/14/09 12:45 PM Page 1 PHILLIP SWAGEL Georgetown University The Financial Crisis: An Inside View ABSTRACT This paper reviews the policy response to the 2007–09 finan- cial crisis from the perspective of a senior Treasury official at the time. Gov- ernment agencies faced severe constraints in addressing the crisis: lack of legal authority for potentially helpful financial stabilization measures, a Con- gress reluctant to grant such authority, and the need to act quickly in the midst of a market panic. Treasury officials recognized the dangers arising from mounting foreclosures and worked to facilitate limited mortgage modifica- tions, but going further was politically unacceptable because public funds would have gone to some irresponsible borrowers. The suddenness of Bear Stearns’ collapse in March 2008 made rescue necessary and led to preparation of emergency options should conditions worsen. The Treasury saw Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s rescue that summer as necessary to calm markets, despite the moral hazard created. After Lehman Brothers failed in September, the Treasury genuinely intended to buy illiquid securities from troubled insti- tutions but turned to capital injections as the crisis deepened. his paper reviews the events associated with the credit market disrup- Ttion that began in August 2007 and developed into a full-blown crisis in the fall of 2008. This is necessarily an incomplete history: events con- tinued to unfold as I was writing it, in the months immediately after I left the Treasury, where I served as assistant secretary for economic policy from December 2006 to the end of the George W.