Running Head: Sustainable Tourism: Assessing the Potential of Massawa and the Dahlak Archipelago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Futures

This article was downloaded by:[Laouris, Yiannis] On: 7 July 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 794800492] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK World Futures Journal of General Evolution Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713393663 Can Information and Mobile Technologies Serve to Close the Economic, Educational, Digital, and Social gaps and Accelerate Development? Yiannis Laouris a; Romina Laouri b a Cyprus Neuroscience & Technology Institute, Lefkosia, Cyprus b Ashoka: Innovators for the Public, Arlington, Virginia, USA Online Publication Date: 01 May 2008 To cite this Article: Laouris, Yiannis and Laouri, Romina (2008) 'Can Information and Mobile Technologies Serve to Close the Economic, Educational, Digital, and Social gaps and Accelerate Development?', World Futures, 64:4, 254 — 275 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/02604020802189534 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02604020802189534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

ERITREA: Future Transitions and Regional Impacts / July 2016

| REGIONAL ANALYSTS NETWORK Es PROGRAMME HUMANITAIRE & DÉVELOPPEMENT ERITREA: Future Transitions and Regional Impacts July 2016 HUMANITARIAN FORESIGHT THINK TANK 1 HUMANITARIAN FORESIGHT THINK TANK ERITREA: Future Transitions and Regional Impacts / July 2016 INTRODUCTION Often dubbed ‘the North Korea of Africa,’ Eritrea has had a tumultuous history that has included exploitation by various competing powers and an international community that has often turned its back on the country’s trials and tribulations. Since independence, Eritrea has been ruled by one man, Isaias Afwerki, and a shifting cadre of freedom fighters who have managed to ride the waves of his erratic tenure. A disastrous border war with Ethiopia, conflicts with Sudan and Djibouti, and Eritrea’s support to rebel groups including al Shabaab isolated the country both regionally and globally. In 2009 and 2011, the UN Security Council imposed sanctions, effectively making Eritrea a pariah state. For several years, the country’s youth have fled by the thousands in order to escape the severe human rights violations including indefinite national service that have characterized the country since 2001. While the country appeared on the verge of collapse during the drought of 2008/2009, the state managed to hold on and was eventually thrown a lifeline in the form of mineral revenues as well as a changing regional security dynamic as Saudi Arabia went to war in Yemen to overthrow the Shia Houthi rebels who took power in 2015. Eritrea is now poised to come back onto the regional stage -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

Second Stage of the Proceedings Between Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation)

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Second stage of the proceedings between Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation) 17 December 1999 VOLUME XXII pp. 335-410 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2006 Part IV Award of the Arbitral Tribunal in the second stage of the proceedings between Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation) Decision of 17 December 1999 Sentence du Tribunal arbitral rendue au terme de la seconde étape de la procédure entre l'Erythrée et la République du Yémen (Délimitation maritime) Décision du 17 décembre 1999 334 ERITREA / YEMEN AWARD OF THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL IN THE SECOND STAGE OF THE PROCEEDINGS BETWEEN ERITREA AND YEMEN (MARI- TIME DELIMITATION), 17 DECEMBER 1999 SENTENCE DU TRIBUNAL ARBITRAL RENDUE AU TERME DE LA SECONDE ÉTAPE DE LA PROCÉDURE ENTRE L'ERYTHRÉE ET LA RÉPUBLIQUE DU YÉMEN (DÉLIMITATION MARITIME), 17 DÉCEMBRE 1999 Median line and historic median line — Methods of measurement — Principle of equidistance — Baselines: high water-line, low water-line, median line - "normal baseline", "straight baseline" — Geodeic line. — Presence of mid sea islands — Principle of proportionality as a test of equi- tableness and not a method of delimitation — Requirement of an equitable solution. Non-geographical relevant circumstances: fishing, security, principle of non-encroachment — Relevance of fishing in acceptance or rejecting the argument as to the line of delimitation: location of fishing areas, economic dependency on fishing, effect of fishing practices on the lines of delimitation — "catastrophic" and "long usage" tests — "artisanal fishing", "industrial fish- ing", and associated rights. The drawing of the initial boundary line does not depend on the existence and the protec- tion of the traditional fishing regime. -

Lara Olson 97 Cardiff Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada Tel: (403) 220-8557/ Email: [email protected]

Lara Olson 97 Cardiff Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada Tel: (403) 220-8557/ Email: [email protected] SUMMARY I have combined leading roles in practitioner-focused research, training, and evaluation of international peacebuilding efforts with academic research and teaching on international peacebuilding and civil wars at the University of Calgary. My goals are to produce insights based on rigorous social science research on peacebuilding processes to advance scholarship as well as inform practical frameworks that improve the effectiveness of international support for peace. EDUCATION DPhil, International Relations, Department of Politics and International Relations (ongoing) University of Oxford, U.K., October 1, 2014-present. I have completed all required coursework, conducted most of my fieldwork and aim to complete the doctorate by 2019. My thesis is titled, “Linking Good and Bad Civil Society: How Local Networks Promote Peace or Renewed Violence in Civil Wars”. The study examines the role of in-group networks and influence in the dynamics of civil wars and peacebuilding and shows how these are impacted by dominant models of transnational support for civil society peacebuilding through studies of Georgia and Kosovo. M.Sc. International Relations (With Distinction) London School of Economics, UK. September 1, 1990–August 31, 1991. I graduated the top student in my year in the M.Sc. program with coursework focused on international political economy and Eastern European and Soviet studies. My thesis, “Midwives to the Market” focused on the role of joint ventures as cooperative economic instruments in shifting East-West political and economic relations. Advanced Russian Language Diploma Lenin Pedagogical Institute, Moscow & University of Alberta, Canada. -

Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa

STUDIES IN AFRICAN SECURITY Turkey, United Arab Emirates and other Middle Eastern States Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa This text is a part of the FOI report Foreign military bases and installations in Africa. Twelve state actors are included in the report: China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, Spain, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States. Middle Eastern states are increasing their military region. Turkey’s political interests are in line with those presence in Africa. Turkey and the United Arab of Qatar on the question of political Islam and the MB, Emirates (UAE), two influential Sunni powers with but clash with the agenda of the UAE and Saudi Arabia. contrary views on regional order and political Islam, The conflict among the Sunni powers has intensified since are expanding their foothold in north-eastern Africa. the Arab Spring in 2010, in particular since the UAE-led Turkey has opened a military training facility in blockade against Qatar in 2017. Eastern Africa has thus Somalia and may build a naval dock for military use become an arena for the rivalry between regional powers in Sudan. The UAE has established bases in Eritrea of the Middle East. and Libya, and is currently constructing a base in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AK party have Somaliland. However, Turkey and UAE are not the strengthened the Sunni Muslim identity of the Turkish only Middle Eastern countries with a military presence state, while de facto approving a neo-Ottoman foreign in Africa. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel, and Iran, also policy that implies a growing focus on the Middle East seem to have military activities on the Horn of Africa. -

Ngos and Conflict Management

RESPONSES TO INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE MANAGING CHAOS CONFERENCE NGOS AND CONFLICT MANAGEMENT Pamela R. Aall UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE CONTENTS Key Points v Preface 1 1 Reframing the Issues 3 2 The Changing Nature of NGOs 5 3 New Roles for NGOs 7 4 The Challenge of Coordination 11 5 NGOs as Conflict Managers 14 Contributors 15 Managing Chaos Conference Agenda 18 About the Author 24 About the Institute 25 v approaches outside of military intervention, including humanitarian relief, preventive ac- tion and conflict resolution, development as- sistance, and institution-building. = Because of the nature of their basic mission, humanitarian relief NGOs are often the first to KEY POINTS arrive on the scene of complex emergencies. Consequently, they are often trapped in the midst of these conflicts as they attempt to carry out their relief operations. Accordingly, this type of NGO has had to broaden its tradi- tional role to include ensuring political stabil- ity and fulfilling basic governmental functions in states plagued with severe crisis. = The changing nature of both conflict and hu- manitarian relief has sparked an examination within the NGO community as well as among officials of the United Nations and its member Reframing the Issues governments of the roles that NGOs should play in preventing, managing, and resolving = The nature of conflict has changed substan- conflict. tially in the post–Cold War era. Instead of wars among nation-states, conflict most often ap- The Changing Nature of NGOs pears now as struggles for power and domi- nance within states, pitting ethnic group = United by a commitment to improving condi- against ethnic group, religion against religion, tions around the world, NGOs otherwise rep- and neighbor against neighbor. -

Ricardo René Larémont Professor of Political Science & Sociology SUNY

1 Ricardo René Larémont Professor of Political Science & Sociology SUNY Binghamton 192 Rutland Road, Brooklyn, NY 11225 Phone: 607-232-0776 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Education Yale University, Ph. D., Political Science, 1995 New York University Law School, J.D., 1979 New York University School of Arts & Sciences, B.A., cum laude, 1976 Academic Positions SUNY Binghamton (Harpur College of Arts & Sciences) Professor of Political Science & Sociology (2006-Present) Associate Professor of Political Science & Sociology (2002-2006) Assistant Professor of Political Science & Sociology (1997-2002) Vassar College Visiting Assistant Professor of Political Science (1995-1996) Administrative Positions SUNY Binghamton Interim Dean, Harpur College of Arts & Sciences (2007-2008) Chair, Sociology Department (2002-2007) Associate Director, Institute of GloBal Cultural Studies (1997-2002) Columbia University Associate Director, Institute of African Studies (1996-1997) 2 Non-Academic Positions WDZZ-FM/WFDF-AM (Flint, Michigan) Station Manager (1987-1990) Health Care Lobbyist and Political Consultant (Washington, DC) Clients included Senator Ted Kennedy, Senator Gary Hart & Mayor and Secretary of State Andrew Young (1984-1987) United House of Representatives, Select Committee on Narcotics (Washington, DC) Professional Staff Member (1980-1984) Awards Carnegie Corporation Scholar on Islam (2007) SUNY Chancellor Award for Excellence in Teaching (2001) Fulbright Research Fellow to Algeria and France (1993) Research Grants 2017 Binghamton University $25,000 2017 Georgetown University CIRS $25,000 2009-2012 Office of Naval Research $1,592,115 2007-2009 Carnegie Corporation $100,000 2000 Carnegie Corporation $260,200 1999 Ford Foundation $173,000 1997 Rockefeller Foundation $17,600 1999 United States Institute of Peace $37,000 1997 United States Department of Education $750,000 Research Fields Islamic Politics; Islamic Law; Ethnic and Religious Conflict; Civil Wars; Conflict Resolution; Civil- Military Relations; Democratization; Migration. -

HRACH GREGORIAN, Ph.D. 1928 Beulah Rd. Vienna, VA 22182 USA Telephone: (571) 214-5293 Fax: (703) 255-6578 E-Mail: Hgregorian@I

HRACH GREGORIAN, Ph.D. 1928 Beulah Rd. Vienna, VA 22182 USA Telephone: (571) 2145293 Fax: (703) 2556578 Email: [email protected] SUMMARY A conflict analysis and management expert, a security and defense analyst, and an organizational management, leadership training and change management specialist with thirty years of experience in the public and private sectors. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1996 – Present Institute of World Affairs, Washington, D.C. President Oversee and manage all operations for an international nongovernmental organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. Responsibilities include strategic planning, program design, program administration, client development, fund-raising, personnel management, budgetary control and public outreach. Design and implement training programs to enhance professional skills in negotiation, mediation, and other forms of conflict management. Design and develop distance education programs. 1999 – Present de novo group, Washington, D.C. President and CEO Owner and operator of a management consulting firm that works with government and commercial clients to enhance organizational performance through well coordinated transformation consultation. Client services include: executive coaching; leadership development; organization behavior assessment and analysis; and design, development, and delivery of management and employee training programs. 2006 – Present Gettysburg Integrated Solutions, Gettysburg, PA -1- Founding Partner An intellectual capital formation and brokering firm specializing in integrated solutions to global security challenges. The firm develops high quality, individually tailored and cost- effective information solutions for government and business clients. An international network of subject matter experts across a wide range of disciplines forms the backbone of business operations. The firm interfaces with research institutes, academic institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and professional societies throughout the world. -

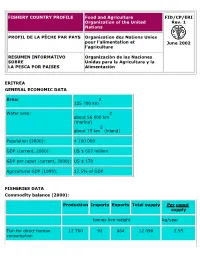

Eritrea General Economic Data

FISHERY COUNTRY PROFILE Food and Agriculture FID/CP/ERI Organization of the United Rev. 1 Nations PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE PAR PAYS Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentation et June 2002 l'agriculture RESUMEN INFORMATIVO Organización de las Naciones SOBRE Unidas para la Agricultura y la LA PESCA POR PAISES Alimentación ERITREA GENERAL ECONOMIC DATA Area: 2 125 700 km Water area: 2 about 56 000 km (marine) 2 about 15 km (inland) Population (2000): 4 100 000 GDP (current, 2000): US $ 607 million GDP per caput (current, 2000): US $ 170 Agricultural GDP (1999): 17.5% of GDP FISHERIES DATA Commodity balance (2000): Production Imports Exports Total supply Per caput supply tonnes live-weight kg/year Fish for direct human 12 700 92 664 12 098 2.95 consumption Fish for animal feed and 1 700 - - 1 700 other purposes Estimated employment (2002): (i) Primary sector: 3 500 (ii) Secondary sector: 10 000 (part time, estimated) Gross value of fisheries output (at ex-vessel prices) 2000: US $5 500 000 (estimated) Trade (2000), estimated: Value of imports US $ 0.1 million Value of exports US $ 2.1 million THE STRUCTURE AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INDUSTRY Marine fisheries 2 Located at the widest part of the Red Sea, Eritrea has an EEZ of 121 000 km . Its mainland coastline is about 1 900 km from the Sudan border to the Jibouti border. Eritrea has a 2 continental shelf of 56 000 km with a plateau containing 360 islands that define the Dahlak Archipelago. The latter add another 1 300 km of coastline. -

ETHIOPIA, RED SEA, and NILE RIVER Previous Science Focus! Articles Have Discussed a Particular Phenomenon That Is Visible in Seawifs Data and Imagery

SCIENCE FOCUS: ETHIOPIA, RED SEA, AND NILE RIVER Previous Science Focus! articles have discussed a particular phenomenon that is visible in SeaWiFS data and imagery. In this case, however, SeaWiFS has provided superb views of a distant region of the world that has many unique geological and physical features. Furthermore, this region of Africa has both archaeological and anthropological significance. Hominid fossils found here indicate that this region may be the origin of humanity's presence on Earth, and the Nile River valley and delta are the home of numerous archaeological sites from the time of the Pharaohs. The SeaWiFS image below is centered on Ethiopia. The sites that are labeled will be discussed on the following pages. The image without labels appears on page 4. Starting at the top right, the capital city of Sudan, Khartoum, is located at the convergence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile. Although the Blue Nile is much shorter than the White Nile, it contributes about 80% of the flow of the river. Moving west, the Dahlak Archipelago is seen off the Red Sea coast of Eritrea. Because of their isolation, the numerous coral reefs of the Dahlak Archipelago are some of the most pristine remaining in the world. Portions of the Dahlak Archipelago are in the Dahlak Marine National Park. Directly south of the Dahlak Archipelago, in the inhospitable desert region of the Afar Triangle and the Danakil Depression, is the active shield volcano Erta Ale. The summit crater of Erta Ale holds an active lava lake. South of Erta Ale, the terminal delta of the Awash River can be seen. -

Lara Olson Dphil Candidate, International Relations, University of Oxford, U.K

Lara Olson DPhil Candidate, International Relations, University of Oxford, U.K. Research Fellow, CMSS, University of Calgary, Canada Consultant, Peacebuilding & Conflict Sensitive Development Email: [email protected], [email protected] SUMMARY I have combined leading roles in practitioner-focused research, training, and evaluation of international peacebuilding efforts with academic research and teaching at the University of Calgary. My goals are to merge field-based research focused on local experiences of international aid with innovative methodologies in the social sciences. My work aims to advance peacebuilding scholarship as well as inform practical frameworks to improve international-national partnerships in peacebuilding and the overall effectiveness of international interventions to support peace. EDUCATION DPhil, International Relations, Department of Politics and International Relations (ongoing) University of Oxford, U.K., October 1, 2014-present. My research explores the dynamics of engagement between transnational actors and local civil society in areas of conflict entitled - Linking Good and Bad Civil Society; How Local Networks Promote Peace or Renewed Violence in Civil Wars. It examines how international aid for civil society promotion impacts the legitimacy of the resulting local civil society and its influence on restraining and controlling violence generated from within its own community. M.Sc. International Relations (With Distinction) London School of Economics, UK. September 1, 1990–August 31, 1991. I specialized in international political economy, and Eastern European/Soviet studies. My thesis, “Midwives to the Market” focused on the role of joint ventures in shifting East-West political and economic relations. Advanced Russian Language Diploma Lenin Pedagogical Institute, Moscow & University of Alberta, Canada.