The Function of the Symposium Theme in Theocritus' I Dyll14 Joan B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Gut-Madness': Gastrimargia in Plato and Beyond

‘GUT-MADNESS’: GASTRIMARGIA IN PLATO AND BEYOND Judy Stove (University of New South Wales) The classical Greeks’ and Romans’ ethical systems focused heavily on virtues, that is to say, on good human attributes. Human vices, in fact, always received much more thorough treatment from Christian writers than pagan writers gave them. Our very notion of a vice is heavily influenced by Christian views of sin. This should not overshadow the fact that pagan writers dealt, to some extent, with habits or actions which later entered the canon of vices or sins (for example, Aristotle in the work commonly called Virtues and Vices). My topic is gastrimargia: the bad habit which, in Greek, means ‘gut-madness’, and which came to be translated as gula in Latin and gluttony in English. Overeating and its visible outcome, obesity, are receiving, in our society, a high level of attention, both official and individual. Yet, to state the obvious, overeating (like drinking too much alcohol) is not something unprecedented in earlier societies. Perhaps not so obviously, it was a feature even of societies of the distant past, in times which we might think were insufficiently wealthy to allow it. Gastrimargia represented, of course, one of those bodily desires the denial of which was critical to both pagan and Christian virtue. In fact, the very commonness of the habit may have been the reason why it seems to have assumed quite an important role in some ethical discussions. Gastrimargia features in two key dialogues of Plato. The first I want to discuss appears in the Phaedo.It is easy to forget how very ascetic Plato makes Socrates, in this dialogue. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Greek Lyric Syllabus

Greek 115 Greek Lyric Grace Ledbetter Fall 2010: Early Greek Poetry and Philosophy This seminar will focus on the development of early Greek poetry and philosophy (including Archilochus, Callinus, Tyrtaeus, Alcaeus, Alcman, Sappho, Hipponax, Mimnermus, Semonides, Solon, Homeric Hymns to Demeter and Apollo, Xenophanes, Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Pindar) paying particular attention to questions of normativity and subversion, exclusivity and inclusion, monstrosity, aristocracy, praise, integration, anxiety, connection, deceit, language, and bees. Required books 1) Hesiod, Theogony. ed. Richard Hamilton, Bryn Mawr Commentary. 2) D. Campbell, Greek Lyric Poetry. 3) Homeric Hymn to Apollo, eds Peter Smith and Lee Pearcy, Bryn Mawr Commentary. 4) Homeric Hymn to Demeter, ed. Julia Haig Gaisser, Bryn Mawr Commentary. 5) Heraclitus: Peri Phuseus, Henry W. Johnston, jr. Bryn Mawr Commentary. 6 Parmenides, eds David Sider and Henry Johnston, Bryn Mawr Commentary. Required work Weekly reading, presentations and discussion Weekly short translation quizzes, marked but not graded Midterm exam Thursday, 10/28 Final exam will be scheduled by registrar (date will be posted Oct. 1) Final Paper due 12/18/10 (topics and drafts due earlier) 1 Week 1 (9/2) Reading: H. Fraenkel, Early Greek Poetry and Philosophy. Individual presentations on Fraenkel Week 2 (9/9) Hesiod. Reading in Greek: Theogony 1‐616 Rest of Theogony in English Works and Days in English M. L. West, Theogony. Introduction + commentary. Week 3 (9/16) Archilochus, Callinus, Tyrtaeus Reading in Greek: all of Archilochus in Campbell + Archilochus, “cologne epode” (text on blackboard) all of Callinus and Tyrtaeus in Campbell Secondary (required) B. Snell, “The Rise of the Individual in the Early Greek Lyric” in his The Discovery of the Mind, ch. -

Aristippus and Xenophon As Plato's Contemporary Literary Rivals and The

E-LOGOS – Electronic Journal for Philosophy 2015, Vol. 22(2) 4–11 ISSN 1211-0442 (DOI 10.18267/j.e-logos.418),Peer-reviewed article Journal homepage: e-logos.vse.cz Aristippus and Xenophon as Plato’s contemporary literary rivals and the role of gymnastikè (γυμναστική) Konstantinos Gkaleas1 Abstrakt: Plato was a Socrates’ friend and disciple, but he wasn’t the only one. No doubt, Socrates had many followers, however, the majority of their work is lost. Was there any antagonism among his followers? Who succeeded in interpreting Socrates? Who could be considered as his successor? Of course, we don’t know if these questions emerged after the death of Socrates, but the Greek doxography suggests that there was a literary rivalry. As we underlined earlier, most unfortunately, we can’t examine all of them thoroughly due to the lack of their work, but we can scrutinize Xenophon’s and Aristippus’ work. All of them, Plato, Xenophon and Aristippus, presented to a certain extent their ideas concerning education. Furthermore, they have not neglected the matter of gymnastikè, but what is exactly the role of physical education in their work? Are there any similarities or any differences between them? Since, Xenophon and Aristippus (as well as Plato) seem to be in favor of gymnastikè, it is necessary to understand its role. Keywords: gymnastikè, Plato, Socrates, Xenophon, Aristippus. 1 Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 12 place du Panthéon, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France, [email protected] Volume 22 | Number 02 | 2015 E-LOGOS – ELECTRONIC JOURNAL FOR PHILOSOPHY 4 Plato is a prominent thinker, whose influence on philosophy is an incontestable fact. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience. -

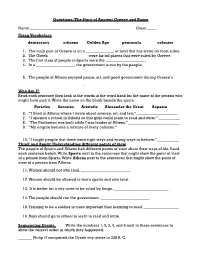

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

The Theoi of Theocritus: Generic Divinity in Idyll 1

The Theoi of Theocritus: Generic Divinity in Idyll 1 It sounds like the beginning of a bad joke: “three gods walk up to a dying cowherd and…” Yet nevertheless, it is under such unusual circumstances that we are first introduced to Theocritus’ bucolic poetry. A programmatic poem designed to establish a new “lower” genre, Idyll 1, in fact, includes more divine figures than mortals. Theocritus’ unusual treatment of divinities begins most strikingly with his portrayal of the Nymphs, but culminates in his depiction of a trio of erotic deities—Hermes, Priapus, and Aphrodite, a set who do not occur together elsewhere in the Idylls. While the invocation of such diverse gods may seem Homeric, the presentation of these divine figures falls short of the expectations and patterns set up by Homer. In their encounters with Daphnis, their divinity is strangely suppressed, and the approaches, attire, and overall portrayal of the gods are reduced to simple, mundane terms that utterly lack the glory of epic. Interpretation of the roles of these gods has varied over time. A. S. F. Gow proposed that Hermes, at least, comes to Daphnis as a fellow herder, a “god of flocks and herds” who reminds the reader of the pastoral environment (1950); Kathryn Gutzwiller, focusing on Daphnis’ conflict with Aphrodite, explains his divine encounters as Theocritus’ attempt to emphasize Daphnis’ mythical prowess in rejecting love (1991); Marco Fantuzzi simply accepted the presence of these deities as a vestige of the mythical background of Daphnis (1998). There is no consensus among scholars; rather, there is a clear dichotomy, as Gow’s interpretation relies on the familiarity of a god and Gutzwiller and Fantuzzi’s on their divinity. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

Pindaric Kleos

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-0319.18.02 Maciej JASZCZYŃSKI PINDARIC KLEOS KLEOS PINDARA Artykuł porusza kwestię funkcjonowania pojęcia sławy - kleos - w Odach zwycięskich Pinda- ra. Pierwszym problemem jest stosunek pomiędzy kleos Pindara a kleos epickim, w szczególności Homeryckim. Staram się odpowiedzieć na pytanie, dlaczego Pindar w bardzo ograniczony sposób korzystał z motywów pochodzących z Iliady i Odysei, natomiast bardzo często sięgał do poezji cyklicznej. Przeprowadzam dokładną analizę ostatnich wersów trzeciej Ody Pytyjskiej w świetle Homeryckiej koncepcji kleos oraz bardzo archaicznej formuły poetyckiej kleos aphthiton. Następ- nie rozważam relację Pindara z wcześniejszymi poetami lirycznymi, głównie na podstawie fragmen - tów z Ibykosa 282a (S151), Elegii Platejskiej Symonidesa, krótko wspominając Stezychora. Staram się pokazać jak koncepcje kleos w tradycji poetyckiej wpłynęły na Pindara. Słowa klucze: Pindar, poezja grecka, tradycja poetycka, kleos. In this article I am going to look at the mechanics of Pindaric In many of his odes, Olympian 1 being a prime example, Pindar was often at pains to renounce the poetic tradition and establish his own authority. However, in terms of conferring glory onto his subject he seems to rely heavily on mythological tradition. In the first part, I shall scrutinise the function of originating from the epic as a means of praise for the victors. Secondly, I shall look at Pindar’s re- lationship to lyric encomiastic tradition, especially Ibycus, Simonides and briefly Stesichorus and their take on in poetry. There are several remark and ob- servations which have to be made before I move on to the discussion. We are not sure about the appropriation of authorship of the cyclic poems in the early fifth century. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC.