Management and Conservation of Renewable Marine Resources in the Indian Ocean Region: Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of Alcyonacean Corals Along Tuticorin Coast of Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 43(4), April 2014, pp. 666-675 Status of Alcyonacean corals along Tuticorin coast of Gulf of Mannar, Southeastern India S. Rajesh, K. Diraviya Raj, G. Mathews, T. Sivaramakrishnan & J.K. Patterson Edward Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute 44-Beach Road, Tuticorin – 628 001, Tamil Nadu, India [E-mail: [email protected]] Received 28 November 2012; revised 7 December 2012 In this study, the assessment of alcyonaceans was conducted in Tuticorin coast of the Gulf of Mannar during the period between 2010 and 2012 in 5 locations; Vaan, Koswari, Kariyachalli and Vilanguchalli islands and mainland Punnakayal patch reef. Average alcyonacean coral cover in Tuticorin coast was 6.76% during 2011-12 which was 5.61% during 2010- 2011. Percentage cover of alcyonacean corals increased in all the study locations; Kariyachalli 12.04 to 13.96%; Vilanguchalli 8.94 to 10.23%; Koswari 1.6 to 3.69; Vaan 0.53 to 0.72; mainland Punnakayal patch reef 4.95 to 5.21% was documented. In total, 15 species from 7 genera were recorded during the study period. Though anthropogenic threats in Tuticorin coast are comparatively high, the abundance of alcyonacean corals has increased considerably showing their resilience and adaptability. [Keywords: Alcyonacean corals, Status, Diversity, Tuticorin, Gulf of Mannar] Introduction experience all the natural and anthropogenic threats. Alcyonacean corals (soft corals and gorgonians) Reef ecosystems of Gulf of Mannar are heavily are modular cnidarians composed of polyps that stressed due to various human induced threats like always have eight tentacles and are oftentimes destructive and over fishing practices, coral mining, connected by vessels classified under subclass domestic and industrial pollution, seaweed and other Octocorallia while hard corals have six tentacles resource collection in reef areas and invasion of (which are hexa corals). -

Reef Encounter Reef Encounter

Volume 30, No. 2 September 2015 Number 42 REEF ENCOUNTER REEF ENCOUNTER United Nations Climate Change Conference Education about Reefs and Climate Change Climate Change: Reef Fish Ecology, Genetic Diversity and Coral Disease Society Honors and Referendum Digital Underwater Cameras Review The News Journal of the International Society for Reef Studies ISSN 0225-27987 REEF ENCOUNTER The News Journal of the International Society for Reef Studies ISRS Information REEF ENCOUNTER Reef Encounter is the magazine style news journal of the International Society for Reef Studies. It was first published in 1983. Following a short break in production it was re-launched in electronic (pdf) form. Contributions are welcome, especially from members. Please submit items directly to the relevant editor (see the back cover for author’s instructions). Coordinating Editor Rupert Ormond (email: [email protected]) Deputy Editor Caroline Rogers (email: [email protected]) Editor Reef Perspectives (Scientific Opinions) Rupert Ormond (email: [email protected]) Editor Reef Currents (General Articles) Caroline Rogers (email: [email protected]) Editors Reef Edge (Scientific Letters) Dennis Hubbard (email: [email protected]) Alastair Harborne (email: [email protected]) Edwin Hernandez-Delgado (email: [email protected]) Nicolas Pascal (email: [email protected]) Editor News & Announcements Sue Wells (email: [email protected]) Editor Book & Product Reviews Walt Jaap (email: [email protected]) INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR REEF STUDIES The International Society for Reef Studies was founded in 1980 at a meeting in Cambridge, UK. Its aim under the constitution is to promote, for the benefit of the public, the production and dissemination of scientific knowledge and understanding concerning coral reefs, both living and fossil. -

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

Information Exchange for Marine Educators

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Educational Programs, Activities, and Websites Environmental and Ocean Literacy Environmental literacy is key to preserving the nation's natural resources for current and future use and enjoyment. An environmentally literate public results in increased stewardship of the natural environment. Many organizations are working to increase the understanding of students, teachers, and the general public about the environment in general, and the oceans and coasts in particular. The following are just some of the large-scale and regional initiatives which seek to provide standards and guidance for our educational efforts and form partnerships to reach broader audiences. (In the interest of brevity, please forgive the abbreviations, the abbreviated lists of collaborators, and the lack of mention of funding institutions). The lists are far from inclusive. Please send additional entries for inclusion in future newsletters. Background Documents Environmental Literacy in America - What 10 Years of NEETF/Roper Research and Related Studies Say About Environmental Literacy in the U.S. http://www.neetf.org/pubs/index.htm The U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy devoted a full chapter on promoting lifelong ocean education, Ocean Stewardship: The Importance of Education and Public Awareness. It reviews the current status of ocean education and provides recommendations for strengthening national educational capacity. http://www.oceancommission.gov/documents/full_color_rpt/08_chapter8.pdf Environmental and Ocean Literacy and Standards Mainstreaming Environmental Education – The North American Association for Environmental Education is involved with efforts to make high-quality environmental education part of all education in the United States and has initiated the National Project for Excellence in Environmental Education. -

Coral Species ID

Coral Species ID Colony shape (branching, mound, plates, column, crust, etc) Colony surface (bumpy, smooth, ridges) Polyp/Corallite Size (small, big) Polyp/Corallite shape (round/elliptical, irregular, y- shaped, „ innies vs outies‟ ridge/valley) Polyp color (green, brown, tan, yellow, olive, red) Different Corallite Shapes and Sizes Examples of Massive Stony Corals Montastraea Montastraea Suleimán © W.Harrigan © faveolata cavernosa S. © Diploria strigosa Porites astreoides © M. White© Montastraea faveolata MFAV Small, round polyps Form very large mounds, plates or crusts (to 4-5 m /12-15 ft) © S. ThorntonS. © Montastraea faveolata MFAV Surfaces smooth, ridged, or with bumps aligned in vertical rows © W. Harrigan © M. Weber © R. Steneck Montastraea faveolata MFAV Colonies are flattened, massive- plates with smooth surfaces under conditions of low light. Montastrea annularis MANN How similar to M. faveolata Small polyps Smooth surface How different Colonies are subdivided into numerous mounds or columns with live polyps at their summits. Plates at colony bases under low light conditions. (to 3-4 m/9-12 ft) Which is which? M. annularis M. faveolata MANN MFAV Montastrea franksi MFRA How similar to M. faveolata Small polyps and bumps Close-up How different Some polyps in bumps are larger, irregularly shaped, and may lack zooxanthellae. More aggressive spatial competitor. © P. Humann Montastrea franksi MFRA How similar to M. faveolata Form mounds, short columns, crusts, and/or plates. How different Bumps are scattered over colony surface. (to 3-4 m/9-12 ft) Montastrea franksi MFRA Flattened, massive plate morphology in low light conditions. Solenastrea bournoni SBOU How similar to M. annularis Small round polyps Mounds How different Lighter colors in life, Walls of some polyps are more distinct (“outies”) Bumpy colony surface (to ~1/2 m/<20 in) Solenastrea hyades SHYA How similar to S. -

Solomon Islands Marine Life Information on Biology and Management of Marine Resources

Solomon Islands Marine Life Information on biology and management of marine resources Simon Albert Ian Tibbetts, James Udy Solomon Islands Marine Life Introduction . 1 Marine life . .3 . Marine plants ................................................................................... 4 Thank you to the many people that have contributed to this book and motivated its production. It Seagrass . 5 is a collaborative effort drawing on the experience and knowledge of many individuals. This book Marine algae . .7 was completed as part of a project funded by the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation Mangroves . 10 in Marovo Lagoon from 2004 to 2013 with additional support through an AusAID funded community based adaptation project led by The Nature Conservancy. Marine invertebrates ....................................................................... 13 Corals . 18 Photographs: Simon Albert, Fred Olivier, Chris Roelfsema, Anthony Plummer (www.anthonyplummer. Bêche-de-mer . 21 com), Grant Kelly, Norm Duke, Corey Howell, Morgan Jimuru, Kate Moore, Joelle Albert, John Read, Katherine Moseby, Lisa Choquette, Simon Foale, Uepi Island Resort and Nate Henry. Crown of thorns starfish . 24 Cover art: Steven Daefoni (artist), funded by GEF/IWP Fish ............................................................................................ 26 Cover photos: Anthony Plummer (www.anthonyplummer.com) and Fred Olivier (far right). Turtles ........................................................................................... 30 Text: Simon Albert, -

EXTENDED COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS of PRESENT and FUTURE USE of INDONESIAN CORAL REEFS an Empirical Approach to Sustainable Management of Tropical Marine Resources

Aus dem Institut für Agrarökonomie der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel EXTENDED COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF PRESENT AND FUTURE USE OF INDONESIAN CORAL REEFS An Empirical Approach to Sustainable Management of Tropical Marine Resources Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Agrar-und Ernährungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Magister of Science Achmad Fahrudin aus Jakarta (Indonesien) Kiel, November 2003 Dekan : Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Taube Erster Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. Christian Noell Zweiter Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. Franciscus Colijn Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 06.11.2003 i Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Agrar- und Ernährungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel ii Zusammenfassung Korallen stellen einen wichtigen Faktor der indonesischen Wirtschaft dar. Im Vergleich zu anderen Ländern weisen die Korallenriffe Indonesiens die höchsten Schädigungen auf. Das zerstörende Fischen ist ein Hauptgrund für die Degradation der Korallenriffe in Indonesien, so dass das Gesamtsystem dieser Fangpraxis analysiert werden muss. Dazu wurden im Rahmen dieser Studie die Standortbedingungen der Korallen erfasst, die Hauptnutzungen mit ihren jeweiligen Auswirkungen und typischen Merkmale der Nutzungen bestimmt sowie die politische Haltung der gegenwärtigen Regierung gegenüber diesem Problemfeld untersucht. Die Feldarbeit wurde in der Zeit von März 2001 bis März 2002 an den Korallenstandorten Seribu Islands (Jakarta), Menjangan Island (Bali) und Gili Islands -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

CORAL REEF DEGRADATION in the INDIAN OCEAN Status Report 2005

Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean Status Report 2005 Coral Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean. The coastal ecosystem of the Indian Ocean includes environments such as mangroves, sea- Program Coordination grass beds and coral reefs. These habitats are some CORDIO Secretariat Coral Reef Degradation of the most productive and diverse environments Olof Lindén on the planet. They form an essential link in the David Souter Department of Biology and Environmental food webs that leads to fish and other seafood in the Indian Ocean Science providing food security to the local human University of Kalmar population. In addition coral reefs and mangrove 29 82 Kalmar, Sweden Status Report 2005 forests protect the coastal areas against erosion. (e-mail: [email protected], Unfortunately, due to a number of human activi- [email protected]) Editors: DAVID SOUTER & OLOF LINDÉN ties, these valuable environments are now being degraded at an alarming rate. The use of destruc- CORDIO East Africa Coordination Center David Obura tive fishing techniques on reefs, coral mining and P.O. Box 035 pollution are examples of some of these stresses Bamburi, Mombasa, Kenya from local sources on the coral reefs. Climate (e-mail: [email protected], change is another stress factor which is causing [email protected]) additional destruction of the reefs. CORDIO is a collaborative research and CORDIO South Asia Coordination Center development program involving expert groups in Dan Wilhelmsson (to 2004) Status Report 2005 countries of the Indian Ocean. The focus of Jerker Tamelander (from 2005) IUCN (World Conservation Union) CORDIO is to mitigate the widespread degrada- 53 Horton Place, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka tion of the coral reefs and other coastal eco- (e-mail: [email protected]) systems by supporting research, providing knowledge, creating awareness, and assist in CORDIO Indian Ocean Islands developing alternative livelihoods. -

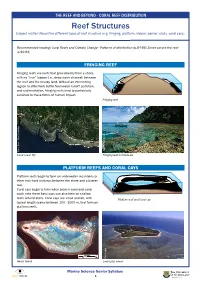

Reef Structures Subject Matter: Recall the Different Types of Reef Structure (E.G

THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures Subject matter: Recall the different types of reef structure (e.g. fringing, platform, ribbon, barrier, atolls, coral cays). Recommended reading: Coral Reefs and Climate Change - Patterns of distribution (p.84-85) Zones across the reef (p.92-94) FRINGING REEF Fringing reefs are reefs that grow directly from a shore, with no “true” lagoon (i.e., deep water channel) between the reef and the nearby land. Without an intervening lagoon to effectively buffer freshwater runoff, pollution, and sedimentation, fringing reefs tend to particularly sensitive to these forms of human impact. Fringing reef Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Planet Dove - Allen Coral Atlas Allen Coral Planet Dove - Coral coast, Fiji Fringing reef in Indonesia. PLATFORM REEFS AND CORAL CAYS Platform reefs begin to form on underwater mountains or other rock-hard outcrops between the shore and a barrier reef. Coral cays begin to form when broken coral and sand wash onto these flats; cays can also form on shallow reefs around atolls. Coral cays are small islands, with Platform reef and Coral cay typical length scales between 100 - 1000 m, that form on platform reefs, Dave Logan Heron Island Lady Elliot Island Marine Science Senior Syllabus 8 THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures BARRIER REEFS BARRIER REEFS are coral reefs roughly parallel to a RIBBON REEFS are a type of barrier reef and are unique shore and separated from it by a lagoon or other body of to Australia. The name relates to the elongated Reef water.The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against bodies starting to the north of Cairns, and finishing to the waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, east of Lizard Island. -

Damage on South African Coral Reefs and an Assessment of Their Sustainable Diving Capacity Using a Fisheries Approach

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 67(3): 1025–1042, 2000 CORAL REEF PAPER DAMAGE ON SOUTH AFRICAN CORAL REEFS AND AN ASSESSMENT OF THEIR SUSTAINABLE DIVING CAPACITY USING A FISHERIES APPROACH Michael H. Schleyer and Bruce J. Tomalin ABSTRACT Coral reefs in a marine reserve at Sodwana Bay (27°30'S) make it a premier dive resort. Corals are at the southern limits of their African distribution on these reefs which are dominated by soft corals. The coastline is exposed and turbulent. An assessment of the degree to which sport diving damages the reefs is needed for their management. This study showed that recognizable diver damage is generally concentrated in heavily dived areas. This damage and that of unknown cause probably attributable to divers exceeded natural damage on the reefs, despite the normally rough seas. Fishing line discarded in angling areas also caused considerable damage by tangling around branching corals which become algal fouled and die. Heaviest damage was caused in isolated areas by a minor crown-of-thorns outbreak. A linear regression indicated that 10% diver damage occurs at 9000 dives per dive site p.a. Taking uncertainty into account, a precautionary limit of 7000 dives per dive site p.a. was recommended. Further recommendations are that the reefs be zoned in terms of their sensitivity to diver damage, depth and use by divers according to qualification, and a ban be placed on the use of diving gloves to reduce handling of the reefs. The complexity and beauty of coral reefs make them an attractive and valuable re- source for ecotourism (Davis and Tisdell, 1995). -

Biodiversity

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument Biodiversity Management Issue Managers require adequate information on the status of biodiversity in order to effectively protect resources of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM or Monument). Description The Monument is the single largest conservation area under the U.S. flag, encompassing 137,797 square miles of the Pacific Ocean. The reefs of the Monument are considered to be in nearly pristine condition. Comprehensive information on the biodiversity of the Monument is needed in order to protect these valuable resources. As an example of how little is known about biodiversity in the Monument, a 2006 Census of Marine Life cruise which focused on non-coral invertebrates and algae found hundreds of new records and several new species. Given that this work occurred only within three miles of French Frigate Shoals, it is reasonable to expect that a similar intensive effort at other areas of the Monument would likely yield comparable results. Furthermore, to date much of the work that has been completed has been focused on shallow-water (<100 ft.) reef ecosystems, research focused on underexplored habitats such as deep reefs, sand habitats, and algal beds will certainly also reveal new records and species. It is clear that much more effort needs to be put into establishing baseline biodiversity data as an essential first step to understanding the ecosystems of the Monument. Questions and Information Needs 1) What is the baseline biodiversity at different sites within the Monument?