Lecture 4: September 15 4.1 Process State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Review for Central Processing Unit Scheduling Algorithm

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 10, Issue 1, No 2, January 2013 ISSN (Print): 1694-0784 | ISSN (Online): 1694-0814 www.IJCSI.org 353 A Comprehensive Review for Central Processing Unit Scheduling Algorithm Ryan Richard Guadaña1, Maria Rona Perez2 and Larry Rutaquio Jr.3 1 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines 2 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines 3 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines Abstract when an attempt is made to execute a program, its This paper describe how does CPU facilitates tasks given by a admission to the set of currently executing processes is user through a Scheduling Algorithm. CPU carries out each either authorized or delayed by the long-term scheduler. instruction of the program in sequence then performs the basic Second is the Mid-term Scheduler that temporarily arithmetical, logical, and input/output operations of the system removes processes from main memory and places them on while a scheduling algorithm is used by the CPU to handle every process. The authors also tackled different scheduling disciplines secondary memory (such as a disk drive) or vice versa. and examples were provided in each algorithm in order to know Last is the Short Term Scheduler that decides which of the which algorithm is appropriate for various CPU goals. ready, in-memory processes are to be executed. Keywords: Kernel, Process State, Schedulers, Scheduling Algorithm, Utilization. 2. CPU Utilization 1. Introduction In order for a computer to be able to handle multiple applications simultaneously there must be an effective way The central processing unit (CPU) is a component of a of using the CPU. -

Parallel Programming in Unix, Many Programs Run in at the Same Time

parallelism parallel programming! to perform a number of tasks simultaneously! these can be calculations, or data transfer or…! In Unix, many programs run in at the same time handling various tasks! we like multitasking…! we don’t like waiting… "1 simplest way: FORK() Each process has a process ID called PID.! After a fork() call, ! there will be a second process with another PID which we call the child. ! The first process, will also continue to exist and to execute commands, we call it the mother. "2 fork() example #include <stdio.h> // printf, stderr, fprintf! ! #include <sys/types.h> // pid_t ! } // end of child! #include <unistd.h> // _exit, fork! else ! #include <stdlib.h> // exit ! { ! #include <errno.h> // errno! ! ! /* If fork() returns a positive number, we int main(void)! are in the parent process! {! * (the fork return value is the PID of the pid_t pid;! newly created child process)! pid = fork();! */! ! int i;! if (pid == -1) {! for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)! fprintf(stderr, "can't fork, error %d\n", {! errno);! printf("parent: %d\n", i);! exit(EXIT_FAILURE);! sleep(1);! }! }! ! exit(0);! if (pid == 0) {! }// end of parent! /* Child process:! ! * If fork() returns 0, it is the child return 0;! process.! } */! int j;! for (j = 0; j < 15; j++) {! printf("child: %d\n", j);! sleep(1);! }! _exit(0); /* Note that we do not use exit() */! !3 why not to fork fork() system call is the easiest way of branching out to do 2 tasks concurrently. BUT" it creates a separate address space such that the child process has an exact copy of all the memory segments of the parent process. -

Technical Evaluation and Legal Opinion of Warden: a Network Forensics Tool, Version 1.0 Author(S): Rod Yazdan, Newton Mccollum, Jennifer Ockerman, Ph.D

NCJRS O FFICE OF JU STI CE PR OG RAM Se ~ N ATIONAL C RIMINAL JUSTICE REFERENCE SERVICE QJA BJS N/J OJJF OVC SMART '~ ..) The author(s) shown below used Federal funding provided by the U.S. Department of Justice to prepare the following resource: Document Title: Technical Evaluation and Legal Opinion of Warden: A Network Forensics Tool, Version 1.0 Author(s): Rod Yazdan, Newton McCollum, Jennifer Ockerman, Ph.D. Document Number: 252944 Date Received: May 2019 Award Number: 2013-MU-CX-K111 This resource has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource is being made publically available through the Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. nl JOHNS HOPKINS ..APPLIED PHYSICS LABORATORY 11100 Johns Hopkins Road • Laurel, Maryland 20723-6099 AOS-18-1223 NIJ RT&E Center Project 15WA October 2018 TECHNICAL EVALUATION AND LEGAL OPINION OF WARDEN: A NETWORK FORENSICS TOOL Version 1.0 Rod Yazdan Newton McCollum Jennifer Ockerman, PhD Prepared for: r I I Nation~/ Institute Nl.I of Justice STRENGTHEN SCIENCE. ADVANCE JUSTICE. Prepared by: The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory 11100 Johns Hopkins Rd. Laurel, MD 20723-6099 Task No.: FGSGJ Contract No.: 2013-MU-CX-K111/115912 This project was supported by Award No. 2013-MU-CX-K111, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. -

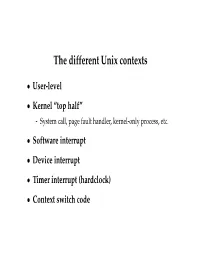

The Different Unix Contexts

The different Unix contexts • User-level • Kernel “top half” - System call, page fault handler, kernel-only process, etc. • Software interrupt • Device interrupt • Timer interrupt (hardclock) • Context switch code Transitions between contexts • User ! top half: syscall, page fault • User/top half ! device/timer interrupt: hardware • Top half ! user/context switch: return • Top half ! context switch: sleep • Context switch ! user/top half Top/bottom half synchronization • Top half kernel procedures can mask interrupts int x = splhigh (); /* ... */ splx (x); • splhigh disables all interrupts, but also splnet, splbio, splsoftnet, . • Masking interrupts in hardware can be expensive - Optimistic implementation – set mask flag on splhigh, check interrupted flag on splx Kernel Synchronization • Need to relinquish CPU when waiting for events - Disk read, network packet arrival, pipe write, signal, etc. • int tsleep(void *ident, int priority, ...); - Switches to another process - ident is arbitrary pointer—e.g., buffer address - priority is priority at which to run when woken up - PCATCH, if ORed into priority, means wake up on signal - Returns 0 if awakened, or ERESTART/EINTR on signal • int wakeup(void *ident); - Awakens all processes sleeping on ident - Restores SPL a time they went to sleep (so fine to sleep at splhigh) Process scheduling • Goal: High throughput - Minimize context switches to avoid wasting CPU, TLB misses, cache misses, even page faults. • Goal: Low latency - People typing at editors want fast response - Network services can be latency-bound, not CPU-bound • BSD time quantum: 1=10 sec (since ∼1980) - Empirically longest tolerable latency - Computers now faster, but job queues also shorter Scheduling algorithms • Round-robin • Priority scheduling • Shortest process next (if you can estimate it) • Fair-Share Schedule (try to be fair at level of users, not processes) Multilevel feeedback queues (BSD) • Every runnable proc. -

Name Synopsis Description

Perl version 5.10.0 documentation - vmsish NAME vmsish - Perl pragma to control VMS-specific language features SYNOPSIS use vmsish; use vmsish 'status';# or '$?' use vmsish 'exit'; use vmsish 'time'; use vmsish 'hushed'; no vmsish 'hushed'; vmsish::hushed($hush); use vmsish; no vmsish 'time'; DESCRIPTION If no import list is supplied, all possible VMS-specific features areassumed. Currently, there are four VMS-specific features available:'status' (a.k.a '$?'), 'exit', 'time' and 'hushed'. If you're not running VMS, this module does nothing. vmsish status This makes $? and system return the native VMS exit statusinstead of emulating the POSIX exit status. vmsish exit This makes exit 1 produce a successful exit (with status SS$_NORMAL),instead of emulating UNIX exit(), which considers exit 1 to indicatean error. As with the CRTL's exit() function, exit 0 is also mappedto an exit status of SS$_NORMAL, and any other argument to exit() isused directly as Perl's exit status. vmsish time This makes all times relative to the local time zone, instead of thedefault of Universal Time (a.k.a Greenwich Mean Time, or GMT). vmsish hushed This suppresses printing of VMS status messages to SYS$OUTPUT andSYS$ERROR if Perl terminates with an error status. and allowsprograms that are expecting "unix-style" Perl to avoid having to parseVMS error messages. It does not suppress any messages from Perlitself, just the messages generated by DCL after Perl exits. The DCLsymbol $STATUS will still have the termination status, but with ahigh-order bit set: EXAMPLE:$ perl -e"exit 44;" Non-hushed error exit%SYSTEM-F-ABORT, abort DCL message$ show sym $STATUS$STATUS == "%X0000002C" $ perl -e"use vmsish qw(hushed); exit 44;" Hushed error exit $ show sym $STATUS $STATUS == "%X1000002C" The 'hushed' flag has a global scope during compilation: the exit() ordie() commands that are compiled after 'vmsish hushed' will be hushedwhen they are executed. -

Processes Process States

Processes • A process is a program in execution • Synonyms include job, task, and unit of work • Not surprisingly, then, the parts of a process are precisely the parts of a running program: Program code, sometimes called the text section Program counter (where we are in the code) and other registers (data that CPU instructions can touch directly) Stack — for subroutines and their accompanying data Data section — for statically-allocated entities Heap — for dynamically-allocated entities Process States • Five states in general, with specific operating systems applying their own terminology and some using a finer level of granularity: New — process is being created Running — CPU is executing the process’s instructions Waiting — process is, well, waiting for an event, typically I/O or signal Ready — process is waiting for a processor Terminated — process is done running • See the text for a general state diagram of how a process moves from one state to another The Process Control Block (PCB) • Central data structure for representing a process, a.k.a. task control block • Consists of any information that varies from process to process: process state, program counter, registers, scheduling information, memory management information, accounting information, I/O status • The operating system maintains collections of PCBs to track current processes (typically as linked lists) • System state is saved/loaded to/from PCBs as the CPU goes from process to process; this is called… The Context Switch • Context switch is the technical term for the act -

Chapter 3: Processes

Chapter 3: Processes Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013 Chapter 3: Processes Process Concept Process Scheduling Operations on Processes Interprocess Communication Examples of IPC Systems Communication in Client-Server Systems Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition 3.2 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013 Objectives To introduce the notion of a process -- a program in execution, which forms the basis of all computation To describe the various features of processes, including scheduling, creation and termination, and communication To explore interprocess communication using shared memory and message passing To describe communication in client-server systems Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition 3.3 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013 Process Concept An operating system executes a variety of programs: Batch system – jobs Time-shared systems – user programs or tasks Textbook uses the terms job and process almost interchangeably Process – a program in execution; process execution must progress in sequential fashion Multiple parts The program code, also called text section Current activity including program counter, processor registers Stack containing temporary data Function parameters, return addresses, local variables Data section containing global variables Heap containing memory dynamically allocated during run time Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition 3.4 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013 Process Concept (Cont.) Program is passive entity stored on disk (executable -

Comparing Systems Using Sample Data

Operating System and Process Monitoring Tools Arik Brooks, [email protected] Abstract: Monitoring the performance of operating systems and processes is essential to debug processes and systems, effectively manage system resources, making system decisions, and evaluating and examining systems. These tools are primarily divided into two main categories: real time and log-based. Real time monitoring tools are concerned with measuring the current system state and provide up to date information about the system performance. Log-based monitoring tools record system performance information for post-processing and analysis and to find trends in the system performance. This paper presents a survey of the most commonly used tools for monitoring operating system and process performance in Windows- and Unix-based systems and describes the unique challenges of real time and log-based performance monitoring. See Also: Table of Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Real Time Performance Monitoring Tools 2.1 Windows-Based Tools 2.1.1 Task Manager (taskmgr) 2.1.2 Performance Monitor (perfmon) 2.1.3 Process Monitor (pmon) 2.1.4 Process Explode (pview) 2.1.5 Process Viewer (pviewer) 2.2 Unix-Based Tools 2.2.1 Process Status (ps) 2.2.2 Top 2.2.3 Xosview 2.2.4 Treeps 2.3 Summary of Real Time Monitoring Tools 3. Log-Based Performance Monitoring Tools 3.1 Windows-Based Tools 3.1.1 Event Log Service and Event Viewer 3.1.2 Performance Logs and Alerts 3.1.3 Performance Data Log Service 3.2 Unix-Based Tools 3.2.1 System Activity Reporter (sar) 3.2.2 Cpustat 3.3 Summary of Log-Based Monitoring Tools 4. -

UNIX X Command Tips and Tricks David B

SESUG Paper 122-2019 UNIX X Command Tips and Tricks David B. Horvath, MS, CCP ABSTRACT SAS® provides the ability to execute operating system level commands from within your SAS code – generically known as the “X Command”. This session explores the various commands, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and their alternatives. The focus is on UNIX/Linux but much of the same applies to Windows as well. Under SAS EG, any issued commands execute on the SAS engine, not necessarily on the PC. X %sysexec Call system Systask command Filename pipe &SYSRC Waitfor Alternatives will also be addressed – how to handle when NOXCMD is the default for your installation, saving results, and error checking. INTRODUCTION In this paper I will be covering some of the basics of the functionality within SAS that allows you to execute operating system commands from within your program. There are multiple ways you can do so – external to data steps, within data steps, and within macros. All of these, along with error checking, will be covered. RELEVANT OPTIONS Execution of any of the SAS System command execution commands depends on one option's setting: XCMD Enables the X command in SAS. Which can only be set at startup: options xcmd; ____ 30 WARNING 30-12: SAS option XCMD is valid only at startup of the SAS System. The SAS option is ignored. Unfortunately, ff NOXCMD is set at startup time, you're out of luck. Sorry! You might want to have a conversation with your system administrators to determine why and if you can get it changed. -

HP Decset for Openvms Guide to the Module Management System

HP DECset for OpenVMS Guide to the Module Management System Order Number: AA–P119J–TE July 2005 This guide describes the Module Management System (MMS) and explains how to get started using its basic features. Revision/Update Information: This is a revised manual. Operating System Version: OpenVMS I64 Version 8.2 OpenVMS Alpha Version 7.3–2 or 8.2 OpenVMS VAX Version 7.3 Windowing System Version: DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS I64 Version 1.5 DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS Alpha Version 1.3–1 or 1.5 DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS VAX Version 1.2–6 Software Version: HP DECset Version 12.7 for OpenVMS Hewlett-Packard Company Palo Alto, California © Copyright 2005 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. Confidential computer software. Valid license from HP required for possession, use or copying. Consistent with FAR 12.211 and 12.212, Commercial Computer Software, Computer Software Documentation, and Technical Data for Commercial Items are licensed to the U.S. Government under vendor’s standard commercial license. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The only warranties for HP products and services are set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. HP shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. Intel and Itanium are trademarks or registered trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries in the United States and other countries. Java is a US trademark of Sun Microsystems, Inc. Microsoft, Windows, and Windows NT are U.S. registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. -

CS 450: Operating Systems Sean Wallace <[email protected]>

Deadlock CS 450: Operating Systems Computer Sean Wallace <[email protected]> Science Science deadlock |ˈdedˌläk| noun 1 [ in sing. ] a situation, typically one involving opposing parties, in which no progress can be made: an attempt to break the deadlock. –New Oxford American Dictionary 2 Traffic Gridlock 3 Software Gridlock mutex_A.lock() mutex_B.lock() mutex_B.lock() mutex_A.lock() # critical section # critical section mutex_B.unlock() mutex_B.unlock() mutex_A.unlock() mutex_A.unlock() 4 Necessary Conditions for Deadlock 5 That is, what conditions need to be true (of some system) so that deadlock is possible? (Not the same as causing deadlock!) 6 1. Mutual Exclusion Resources can be held by process in a mutually exclusive manner 7 2. Hold & Wait While holding one resource (in mutex), a process can request another resource 8 3. No Preemption One process can not force another to give up a resource; i.e., releasing is voluntary 9 4. Circular Wait Resource requests and allocations create a cycle in the resource allocation graph 10 Resource Allocation Graphs 11 Process: Resource: Request: Allocation: 12 R1 R2 P1 P2 P3 R3 Circular wait is absent = no deadlock 13 R1 R2 P1 P2 P3 R3 All 4 necessary conditions in place; Deadlock! 14 In a system with only single-instance resources, necessary conditions ⟺ deadlock 15 P3 R1 P1 P2 R2 P2 Cycle without Deadlock! 16 Not practical (or always possible) to detect deadlock using a graph —but convenient to help us reason about things 17 Approaches to Dealing with Deadlock 18 1. Ostrich algorithm (Ignore it and hope it never happens) 2. -

Windows Operations Agent User Guide

Windows Operations Agent User Guide 1.6 VMC-WAD VISUAL Message Center Windows Operations Agent User Guide The software described in this book is furnished under a license agreement and may be used only in accordance with the terms of the agreement. Copyright Notice Copyright © 2013 Tango/04 All rights reserved. Document date: August 2012 Document version: 2.31 Product version: 1.6 No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, electronic mechani- cal, magnetic, optical, chemical, manual, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Tango/04. Trademarks Any references to trademarked product names are owned by their respective companies. Technical Support For technical support visit our web site at www.tango04.com. Tango/04 Computing Group S.L. Avda. Meridiana 358, 5 A-B Barcelona, 08027 Spain Tel: +34 93 274 0051 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents.............................................................................. iii How to Use this Guide.........................................................................x Chapter 1 Introduction ......................................................................................1 1.1. What You Will Find in this User Guide............................................................2 Chapter 2 Configuration ....................................................................................3 2.1. Monitor Configuration......................................................................................3