Mapping the 24-Hour Emergency Department Cycle to Improve Shari J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist Implementation Guide Improving the Quality of Facility-Based Delivery for Mothers and Newborns

BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist Implementation Guide Improving the quality of facility-based delivery for mothers and newborns WHO SAFE CHILDBIRTH CHECKLIST IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE 1 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO safe childbirth checklist implementation guide: improving the quality of facility-based delivery for mothers and newborns. 1.Parturition. 2.Birthing Centers. 3.Perinatal Care. 4.Maternal Health Services. 5.Infant, Newborn. 6.Quality of Health Care. 7.Checklist. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154945 5 (NLM classification: WQ 300) © World Health Organization 2015 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organiza- tion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

16. Questions and Answers

16. Questions and Answers 1. Which of the following is not associated with esophageal webs? A. Plummer-Vinson syndrome B. Epidermolysis bullosa C. Lupus D. Psoriasis E. Stevens-Johnson syndrome 2. An 11 year old boy complains that occasionally a bite of hotdog “gives mild pressing pain in his chest” and that “it takes a while before he can take another bite.” If it happens again, he discards the hotdog but sometimes he can finish it. The most helpful diagnostic information would come from A. Family history of Schatzki rings B. Eosinophil counts C. UGI D. Time-phased MRI E. Technetium 99 salivagram 3. 12 year old boy previously healthy with one-month history of difficulty swallowing both solid and liquids. He sometimes complains food is getting stuck in his retrosternal area after swallowing. His weight decreased approximately 5% from last year. He denies vomiting, choking, gagging, drooling, pain during swallowing or retrosternal pain. His physical examination is normal. What would be the appropriate next investigation to perform in this patient? A. Upper Endoscopy B. Upper GI contrast study C. Esophageal manometry D. Modified Barium Swallow (MBS) E. Direct laryngoscopy 4. A 12 year old male presents to the ER after a recent episode of emesis. The parents are concerned because undigested food 3 days old was in his vomit. He admits to a sensation of food and liquids “sticking” in his chest for the past 4 months, as he points to the upper middle chest. Parents relate a 10 lb (4.5 Kg) weight loss over the past 3 months. -

Early Skin-To-Skin Contact for Mothers and Their Healthy Newborn Infants (Review)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants (Review) Moore ER, Bergman N, Anderson GC, Medley N Moore ER, Bergman N, Anderson GC, Medley N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD003519. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub4. www.cochranelibrary.com Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants (Review) Copyright © 2016 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 7 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 9 METHODS ...................................... 9 RESULTS....................................... 14 Figure1. ..................................... 15 Figure2. ..................................... 16 Figure3. ..................................... 17 Figure4. ..................................... 21 DISCUSSION ..................................... 27 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 29 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 30 REFERENCES ..................................... 30 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 42 DATAANDANALYSES. 112 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Immediate or Early skin-to-skin versus standard contact for healthy infants, Outcome 1 Breastfeeding 1 month to 4 months post birth. ......... 116 Analysis -

Skilled Nursing Facility 3-Day Rule Billing

Print-Friendly Version Skilled Nursing Facility 3-Day Rule Billing Copyright © 2020, the American Hospital Association, Chicago, Illinois. Reproduced with permission. No portion of the American Hospital Association (AHA) copyrighted materials contained within this publication may be copied without the express written consent of the AHA. AHA copyrighted materials including the UB-04 codes and descriptions may not be removed, copied, or utilized within any software, product, service, solution or derivative work without the written consent of the AHA. If an entity wishes to utilize any AHA materials, please contact the AHA at 312-893-6816. Making copies or utilizing the content of the UB-04 Manual, including the codes and/or descriptions, for internal purposes, resale and/or to be used in any product or publication; creating any modified or derivative work of the UB-04 Manual and/or codes and descriptions; and/or making any commercial use of UB-04 Manual or any portion thereof, including the codes and/or descriptions, is only authorized with an express license from the American Hospital Association. To license the electronic data file of UB-04 Data Specifications, contact Tim Carlson at (312) 893-6816 or Laryssa Marshall at (312) 893-6814. You may also contact us at [email protected]. The American Hospital Association (the “AHA”) has not reviewed, and is not responsible for, the completeness or accuracy of any information contained in this material, nor was the AHA or any of its affiliates, involved in the preparation of this material, or the analysis of information provided in the material. The views and/or positions presented in the material don’t necessarily represent the views of the AHA. -

Deaf-Friendly

Hospitals, Doctors & You: All Working Together Matthew J. Starr, MPH Denise Thew, PhD Rochester, NY Rochester, NY Contributors Mike McKee, MD, MPH Scott Smith, MD, MPH Who Are We? Deaf since birth Deaf at age 2 Born in New York City Born in Vancouver, BC P.S. 47 & Lexington (Early Grades) Mainstreamed Schools NTID at RIT (1979) University of North Dakota Worked at Hospital (10 years) Interned at Regions Hospital Worked at Deaf Interned MSAD & Hard of Hearing Services (18 years) Deaf Wellness Center at Currently at NCDHR University of Rochester Medical Center and NCDHR Workshop Process Informal Can ask questions anytime Presenters will sign questions from participants before answering Internet Links Where can I have this workshop information? What will I learn? How to get best health care Different types of health care Inappropriate Emergency Department use Working with medical interpreters Family Health History End-of-life Issues Taking care of yourself Types of Health Care Primary Care Specialty Care Emergent Care Urgent Care Preventive Health Care Emergent Care Demand an immediate attention & action to save a life and/or minimize permanent injury. Examples: Heart attack, burns, car accident, seizures* Golden Hour Emergency Department (ED) Found in hospitals 24/7 How to get there? (No appointments) Ambulance Walk-in Doctor referral Helicopter GO to an Emergency Department! If you have this, call 9-1-1! Loss of consciousness Unexplained drowsiness or disorientation Shortness of breath Sudden, -

Urgent Care / Same-Day Clinics Emergency Rooms (Open 24 Hours)

Urgent Care / Same-Day Clinics Emergency Rooms (Open 24 Hours) (*) CVS MinuteClinic (Kent) (*/#) UH Kent Health Center (Emergency Room) (330) 678-4009 (330) 677-7680 500 South Water St. Kent, Ohio 44240 411 Devon Place, Kent, Ohio 44240 1.9 mi—about 8 minutes 3.4 mi—about 9 minutes Hours: M-F 9 am—8 pm, Sat 9 am—5:30 pm Sun 10 am—5:30 pm (*/#) University Hospitals Portage Medical Center (330) 297-0811 (*) AxessPointe Community Health Center 6847 North Chestnut St. Ravenna, Ohio 44266 (330) 673-1016 6.91 mi—about 13 minutes 143 Gougler Ave., Kent, Ohio 44240-7609 2 mi—about 8 minutes (*/#) Akron General Health & Wellness Center Hours: M-F 8 am—6 pm, Sat 8 am—2pm (330) 945-9300 4300 Allen Rd. Stow, Ohio 44224 (*/#) UH Kent Health Center (Urgent Care) 9.91 mi—about 20 minutes (330) 677-7681 411 Devon Place, Kent, Ohio 44240 (*/#) Western Reserve Hospital 3.4 mi—about 9 minutes (330) 971-7000 Hours: 9 am—9 pm, 7 days a week 1900 23rd St. Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio 44223 11.05 mi—about 20 minutes (*/#) Cleveland Clinic Akron General Express Care (330) 344-1600 (*) Cleveland Clinic Family Health & Surgery Center 4494 State Route 43 Kent, Ohio 44240 (330) 888-4000 4.8 mi—about 10 minutes 8701 Darrow Rd. Twinsburg, Ohio 44087 Hours: M-F 8 am—9 pm Sat 8 am—4 pm 15 mi—about 20 minutes Closed Sunday (*/#) Summa Akron City Hospital (*/#) Western Reserve Hospital Urgent Care (330) 375-3361 (330) 688-7900 525 East Market St. -

The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies

Strategies to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity For Free Copies Download http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding E-mail [email protected] Write The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1600 Clifton Rd. Atlanta, GA 30333 Call 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636); TTY: 1-888-232-6348 Suggested Citation Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategies to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases: The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. Web site addresses of nonfederal organizations are provided solely as a service to readers. Provision of an address does not constitute an endorsement of this organization by CDC or the federal government, and none should be inferred. CDC is not responsible for the content of other organizations’ Web pages. Strategies to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity ii Contents Using This Guide ........................................................................................................................... -

Doctor, Retail Clinic, Urgent Care Or ER?

Doctor, Retail Clinic, Urgent Care or ER? Quick reference guide for PPO network treatment resources Sometimes it’s easy to know when you should go to an emergency room (ER), such as when you have severe chest pain or unstoppable bleeding. At other times, it’s less clear. Where do you go when you have an ear infection or are not feeling well? The emergency room is an option, but it can be an expensive one. You have choices for receiving in-network care that works with your schedule and gives you access to the kind of care you need. Know when to use each for nonemergency treatment. Care Option Hours Your Relative Cost* Description Doctor’s Office Office hours vary Usually lower Your doctor’s office is generally the best place to go for out-of-pocket cost to nonemergency care such as health exams, colds, flu, sore throats you than urgent care and minor injuries. Retail Health Clinic Similar to retail Usually lower Walk-in clinics are often located in stores and pharmacies to provide store hours out-of-pocket cost to convenient, low-cost treatment for minor medical problems like ear you than urgent care infections, athlete’s foot, bronchitis and some vaccinations. Urgent Care Provider Generally includes Usually lower cost than Urgent care centers can provide care when your doctor is not evenings, weekends an ER visit available and you don’t have a true emergency, but need immediate and holidays care. For example, they can treat sprained ankles, fevers, and minor cuts and injuries. Emergency Room (ER) 24 hours, seven days Highest out-of-pocket For medical emergencies, call 911 or your local emergency a week cost to you services first. -

St. Francis Tire

& Bird City Times $125 8 Pages Thursday, November 19, 2020 136th Year, Number 47 Holiday event being planned By Amanda Moberly [email protected] Several St. Francis residents are working together to make sure there is a parade, Santa Claus and Christmas fun planned this year. The three local banks, along with some help from local businesses, have planned a Holidaze 2020 celebration for Thursday, Dec. SENIOR INDIAN SHADRYON BLANKA, 12, pushes his way through the Bluejay defenders with the help of teammates in 10! There will be a parade that both the above and below pictures. Photos by Rian Zimbal evening, complete with Santa and Mrs. Claus, followed by a Christ- mas Cruise down Main Street. Look for more information Bankwest, FNB Bank, and on the upcoming event in The Western State Bank are working St. Francis Herald and Bird City Indians blow away Bluejays, together with other local Times. businesses and organizations If thereto is anyone willing to bring the Christmas eventsdonate towardsto the event, please the community. The Christmas contact one of the banks. celebration this year, which they Everyone else, please mark advancing team to sub-state! are calling Holidaze 2020, will down Holidaze in St. Francis on be unlike in past years. This year, your calendars for Dec. 10 for By Adam Krien expect something different! some Christmas cheer! The wind did not slow down the Indians in their Saturday af- ternoon game played against the Caldwell Bluejays. The Indians started on defense and was able to get a quick three and out to get the ball and march down the field to score. -

Let's Talk Motherhood: a Guide to Postpartum from GEHA

Let’s talk motherhood A postpartum guide Adapted from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Contents 02 Contents 03 Introduction 06 Healthy baby information 12 Healing after labor and delivery 19 Exercise and nutrition 22 Resources Congratulations on your new baby! You are about to enter an exciting new phase of life. There will be plenty of sleepless nights, heartwarming cuddles and new challenges. This guide is intended to help keep you on track as your baby’s health progresses, make you feel less alone as your body changes after pregnancy and provide resources for further help. GEHA is proud to be your partner in this new life chapter. Adapted from Your Pregnancy and Childbirth Month to Month 02 geha.com/Maternity | Elevate and Elevate Plus by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Introduction Your first well-child visit should be two or three days after coming home from the hospital. Schedule of well-baby visits As a parent, you want your child to be healthy and develop normally. That’s why well-child doctor visits are so important, particularly in the first 15 months of life. Your child’s doctor can help you identify developmental milestones in your child’s physical, mental, language and social skills. Each well-child visit will include a complete physical examination. The doctor will check your baby’s growth and development and record your child’s height, weight and other important information. Tests for hearing, vision and other functions will be part of some visits. First year visits Second year visits Visits occur at ages one, two, four, six and Visits occur at ages 12, 15, 18 and 24 months. -

OASIS Questions and Answers

OASIS Coordinators' Conference Reference Manual Tab 7: OASIS Questions and Answers Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services RM-429 OASIS Coordinators' Conference Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services RM-430 OASIS Coordinators' Conference CATEGORY 1 – APPLICABILITY [Q&A EDITED 09/09] Q1. To whom do the OASIS requirements apply? A1. The comprehensive assessment and OASIS data collection requirements apply to Medicare certified home health agencies (HHAs) and to Medicaid home health providers in States where those agencies are required to meet the Medicare Conditions of Participation. The comprehensive assessment requirement currently applies to all patients regardless of pay source, including Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare managed care (now known as Medicare Advantage), Medicaid managed care, and private pay/including commercial insurance. The comprehensive assessment must include OASIS items for all skilled Medicare, Medicaid, and Medicare or Medicaid managed care patients with the following exceptions: patients under the age of 18, patients receiving maternity services, patients receiving only chore or housekeeping services, and patients receiving only a single visit in a quality episode. Section 704 of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 temporarily suspended OASIS data collection for non-Medicare and non-Medicaid patients. OASIS requirements for patients receiving only personal care (non-skilled) services have been delayed since 1999. The transmission requirement currently applies to Medicare and Medicaid patients receiving skilled care only. Note: The Medicare PPS reimbursement system requires a PPS (HHRG/HIPPS) code to be submitted on the claim of any Medicare PPS patient under 18 or receiving maternity services. While the OASIS data set was not designed for these population types, and is not required by regulation to be collected, in these rare instances, HHAs desiring to receive payment under Medicare PPS would need to collect the data necessary to generate a HHRG/ HIPPS code. -

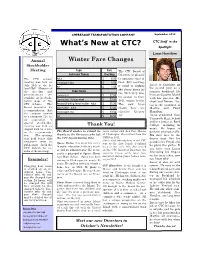

What's New at CTC?

CHEBEAGUE TRANSPORTATION COMPANY September 2012 What’s New at CTC? CTC Staff in the Spotlight Lucas Hamilton Annual Winter Fare Changes Stockholder Meeting Type Fare The CTC Board of Individual Tickets One Way Directors is pleased The CTC annual Adult $ 6.50 to announce that at meeting was held on Child (Age 6-11)) $ 1.50 their July meeting, July 28th at the Is- it voted to reduce Lucas is finishing up Pet $ 1.50 his second year as a land Hall. Minutes of the ferry fares for the meeting and Ticket Books summer deckhand. He the 2012-2013 win- presentations are Commuters $ 27.00 lives on Cousins Island available on the Stock- ter season to their with his parents, Mi- Commuters - Holiday week $ 22.00 holder page of the 2011 winter levels. chael and Denise. Lu- CTC website. The Resident/Parking Permit Holder - Adult $ 35.00 The new fares cas is the grandson of Board presented its Stockholder - Adult $ 52.00 shown here are Martha and Floyd recommendation that effective October Hamilton. the company convert Child (Age 6-11)) $ 23.50 1st. Lucas graduated from to a non-profit 501 (c) Pet $ 26.50 Yarmouth High School (3) corporation. A special stockholder and is a junior at Bard meeting was held on Thank You! College, majoring in August 25th for a vote music. He hopes to on the recommenda- The Board wishes to extend its route carrier and then Post Master perform professionally. tion. (The meeting thanks to the Directors who left of Chebeague. She retired from the His first love is the was held before this the CTC Board during 2012.