The CDC Guide to Strategies to Support Breastfeeding Mothers and Babies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist Implementation Guide Improving the Quality of Facility-Based Delivery for Mothers and Newborns

BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist Implementation Guide Improving the quality of facility-based delivery for mothers and newborns WHO SAFE CHILDBIRTH CHECKLIST IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE 1 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO safe childbirth checklist implementation guide: improving the quality of facility-based delivery for mothers and newborns. 1.Parturition. 2.Birthing Centers. 3.Perinatal Care. 4.Maternal Health Services. 5.Infant, Newborn. 6.Quality of Health Care. 7.Checklist. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154945 5 (NLM classification: WQ 300) © World Health Organization 2015 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organiza- tion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Common Breastfeeding Questions

Common Breastfeeding Questions How often should my baby nurse? Your baby should nurse 8-12 times in 24 hours. Baby will tell you when he’s hungry by “rooting,” sucking on his hands or tongue, or starting to wake. Just respond to baby’s cues and latch baby on right away. Every mom and baby’s feeding patterns will be unique. Some babies routinely breastfeed every 2-3 hours around the clock, while others nurse more frequently while awake and sleep longer stretches in between feedings. The usual length of a breastfeeding session can be 10-15 minutes on each breast or 15-30 minutes on only one breast; just as long as the pattern is consistent. Is baby getting enough breastmilk? Look for these signs to be sure that your baby is getting enough breastmilk: Breastfeed 8-12 times each day, baby is sucking and swallowing while breastfeeding, baby has 3- 4 dirty diapers and 6-8 wet diapers each day, the baby is gaining 4-8 ounces a week after the first 2 weeks, baby seems content after feedings. If you still feel that your baby may not be getting enough milk, talk to your health care provider. How long should I breastfeed? The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends mothers to breastfeed for 12 months or longer. Breastmilk contains everything that a baby needs to develop for the first 6 months. Breastfeeding for at least the first 6 months is termed, “The Golden Standard.” Mothers can begin breastfeeding one hour after giving birth. -

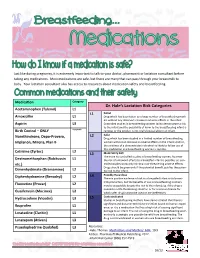

Dr. Hale's Lactation Risk Categories

Just like during pregnancy, it is extremely important to talk to your doctor, pharmacist or lactation consultant before taking any medications. Most medications are safe, but there are many that can pass through your breastmilk to baby. Your lactation consultant also has access to resources about medication safety and breastfeeding. Medication Category Dr. Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories Acetaminophen (Tylenol) L1 L1 Safest Amoxicillin L1 Drug which has been taken by a large number of breastfeeding moth- ers without any observed increase in adverse effects in the infant. Aspirin L3 Controlled studies in breastfeeding women fail to demonstrate a risk to the infant and the possibility of harm to the breastfeeding infant is Birth Control – ONLY Acceptable remote; or the product is not orally bioavailable in an infant. L2 Safer Norethindrone, Depo-Provera, Drug which has been studied in a limited number of breastfeeding Implanon, Mirena, Plan B women without an increase in adverse effects in the infant; And/or, the evidence of a demonstrated risk which is likely to follow use of this medication in a breastfeeding woman is remote. Cetrizine (Zyrtec) L2 L3 Moderately Safe There are no controlled studies in breastfeeding women, however Dextromethorphan (Robitussin L1 the risk of untoward effects to a breastfed infant is possible; or, con- etc.) trolled studies show only minimal non-threatening adverse effects. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the poten- Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) L2 tial risk to the infant. L4 Possibly Hazardous Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) L2 There is positive evidence of risk to a breastfed infant or to breast- milk production, but the benefits of use in breastfeeding mothers Fluoxetine (Prozac) L2 may be acceptable despite the risk to the infant (e.g. -

Melasma (1 of 8)

Melasma (1 of 8) 1 Patient presents w/ symmetric hyperpigmented macules, which can be confl uent or punctate suggestive of melasma 2 DIAGNOSIS No ALTERNATIVE Does clinical presentation DIAGNOSIS confirm melasma? Yes A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Monotherapy • Hydroquinone or • Tretinoin TREATMENT Responding to No treatment? See next page Yes Continue treatment © MIMSas required Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. Specifi c prescribing information may be found in the latest MIMS. B94 © MIMS 2019 Melasma (2 of 8) Patient unresponsive to initial therapy MELASMA A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Dual Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin or • Azelaic acid Responding to Yes Continue treatment treatment? as required No A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen • Laser therapy • Dermabrasion B Pharmacological therapy Triple Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin plus • Topical steroid Chemical peels 1 MELASMA • Acquired hyperpigmentary skin disorder characterized by irregular light to dark brown macules occurring in the sun-exposed areas of the face, neck & arms - Occurs most commonly w/ pregnancy (chloasma) & w/ the use of contraceptive pills - Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis are photosensitizing medications, genetic factors, mild ovarian or thyroid dysfunction, & certain cosmetics • Most commonly aff ects Fitzpatrick skin phototypes III & IV • More common in women than in men • Rare before puberty & common in women during their reproductive years • Solar & ©ultraviolet exposure is the mostMIMS important factor in its development Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. -

The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration: Empowering the Healthcare Team

The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration: Empowering the Healthcare Team By Kathryn A. Spiegel A Master’s Paper submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in the Public Health Leadership Program. Chapel Hill 2009 ___________________________ Advisor signature/printed name ________________________________ Second Reader Signature/printed name ________________________________ Date The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration 2 Abstract Experts and scientists agree that human milk is the best nutrition for human babies, but are healthcare professionals (HCPs) seizing the opportunity to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding? Not only are HCPs influential to the breastfeeding dyad, they hold a responsibility to perform evidence-based interventions to lengthen the duration of breastfeeding due to the extensive health benefits for mother and baby. This paper examines current HCPs‘ education, practices, attitudes, and extraneous factors to surface any potential contributing factors that shed light on necessary actions. Recommendations to empower HCPs to provide consistent, evidence-based care for the breastfeeding dyad include: standardized curriculum in medical/nursing school, continued education for maternity and non-maternity settings, emphasis on skin-to-skin, enforcement of evidence-based policies, implementation of ‗Baby-Friendly USA‘ interventions, and development of peer support networks. Requisite resources such as lactation consultants as well as appropriate medication and breastfeeding clinical management references aid HCPs in providing best practices to increase breastfeeding duration. The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration 3 The key to increasing breastfeeding duration: Empowering the healthcare team During the colonial era, mothers breastfed through their infants‘ second summer. -

Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 1 Virtual Lactation

Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 1 Virtual Lactation Support for Breastfeeding Mothers During the Early Postpartum Period Shakeema S. Jordan College of Nursing, East Carolina University Doctor of Nursing Practice Program Dr. Tracey Bell April 30, 2021 Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 2 Notes from the Author I want to express a sincere thank you to Ivy Bagley, MSN, FNP-C, IBCLC for your expertise, support, and time. I also would like to send a special thank you to Dr. Tracey Bell for your support and mentorship. I dedicate my work to my family and friends. I want to send a special thank you to my husband, Barry Jordan, for your support and my two children, Keith and Bryce, for keeping me motivated and encouraged throughout the entire doctorate program. I also dedicate this project to many family members and friends who have supported me throughout the process. I will always appreciate all you have done. Through my personal story and the doctorate program journey, I have learned the importance of breastfeeding self-efficacy and advocacy. I understand the impact an adequate support system, education, and resources can have on your ability to reach your individualized breastfeeding goals. Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 3 Abstract Breastmilk is the clinical gold standard for infant feeding and nutrition. Although maternal and child health benefits are associated with breastfeeding, national, state, and local rates remain below target. In fact, 60% of mothers do not breastfeed for as long as intended. During the early postpartum period, mothers cease breastfeeding earlier than planned due to common barriers such as lack of suckling, nipple rejection, painful breast or nipples, latching or positioning difficulties, and nursing demands. -

Breastfeeding Guide Lactation Services Department Breastfeeding: Off to a Great Start

Breastfeeding Guide Lactation Services Department Breastfeeding: Off to a Great Start Offer to feed your baby: • when you see and hear behaviors that signal readiness to feed. Fussiness and hand to mouth motions may signal hunger. At other times, your baby is asking to be held or changed. He may be showing signs of being over-stimulated or tired. • until satisfied. In the early weeks and months, feeding lengths vary from 10 to 40 minutes per side. Offer both breasts at each feeding. Your baby may not always take the second side. Expect your baby to cluster feed to increase your milk supply, especially when going through growth spurts. • at least every 1 ½ to 3 hours during the day and a little less frequently at night. Time feedings from the start of one feeding to the start of the next. Most mothers are able to produce enough milk and do NOT need to supplement with formula. • using proper positioning. Turn your baby toward you while breastfeeding. With a wide open mouth, she takes in the areola along with the nipple. The cheeks and chin are touching the breast. Expect your baby to pause between suckle bursts. It is okay to gently stimulate her to suckle throughout the feeding. Your baby is getting enough breastmilk IF: • you hear audible swallows when your baby pauses between suckle bursts. You will hear them more often as your milk changes 24 Hours from colostrum to mature milk. st at least 6 feedings • there are 6 or more wet diapers by day 6. This number will 1 1 wet and 1 stool remain fairly constant after the first week. -

16. Questions and Answers

16. Questions and Answers 1. Which of the following is not associated with esophageal webs? A. Plummer-Vinson syndrome B. Epidermolysis bullosa C. Lupus D. Psoriasis E. Stevens-Johnson syndrome 2. An 11 year old boy complains that occasionally a bite of hotdog “gives mild pressing pain in his chest” and that “it takes a while before he can take another bite.” If it happens again, he discards the hotdog but sometimes he can finish it. The most helpful diagnostic information would come from A. Family history of Schatzki rings B. Eosinophil counts C. UGI D. Time-phased MRI E. Technetium 99 salivagram 3. 12 year old boy previously healthy with one-month history of difficulty swallowing both solid and liquids. He sometimes complains food is getting stuck in his retrosternal area after swallowing. His weight decreased approximately 5% from last year. He denies vomiting, choking, gagging, drooling, pain during swallowing or retrosternal pain. His physical examination is normal. What would be the appropriate next investigation to perform in this patient? A. Upper Endoscopy B. Upper GI contrast study C. Esophageal manometry D. Modified Barium Swallow (MBS) E. Direct laryngoscopy 4. A 12 year old male presents to the ER after a recent episode of emesis. The parents are concerned because undigested food 3 days old was in his vomit. He admits to a sensation of food and liquids “sticking” in his chest for the past 4 months, as he points to the upper middle chest. Parents relate a 10 lb (4.5 Kg) weight loss over the past 3 months. -

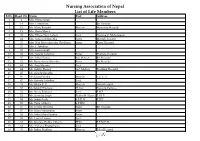

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Breastfeeding Contraindications

WIC Policy & Procedures Manual POLICY: NED: 06.00.00 Page 1 of 1 Subject: Breastfeeding Contraindications Effective Date: October 1, 2019 Revised from: October 1, 2015 Policy: There are very few medical reasons when a mother should not breastfeed. Identify contraindications that may exist for the participant. Breastfeeding is contraindicated when: • The infant is diagnosed with classic galactosemia, a rare genetic metabolic disorder. • Mother has tested positive for HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome) or has Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). • The mother has tested positive for human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type I or type II (HTLV-1/2). • The mother is using illicit street drugs, such as PCP (phencyclidine) or cocaine (exception: narcotic-dependent mothers who are enrolled in a supervised methadone program and have a negative screening for HIV and other illicit drugs can breastfeed). • The mother has suspected or confirmed Ebola virus disease. Breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated when: • The mother is infected with untreated brucellosis. • The mother has an active herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection with lesions on the breast. • The mother is undergoing diagnostic imaging with radiopharmaceuticals. • The mother is taking certain medications or illicit drugs. Note: mothers should be provided breastfeeding support and a breast pump, when appropriate, and may resume breastfeeding after consulting with their health care provider to determine when and if their breast milk is safe for their infant and should be provided with lactation support to establish and maintain milk supply. Direct breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated and the mother should be temporarily isolated from her infant(s) but expressed breast milk can be fed to the infant(s) when: • The mother has untreated, active Tuberculosis (TB) (may resume breastfeeding once she has been treated approximately for two weeks and is documented to be no longer contagious). -

Lawrlwytho'r Atodiad Gwreiddiol

Operational services structure April 2021 14/04/2021 Operational Leadership Structures Director of Operations Director of Nursing & Quality Medical Director Lee McMenamy Joanne Hiley Dr Tessa Myatt Medical Operations Operations Clinical Director of Operations Deputy Director of Nursing & Deputy Medical Director Hazel Hendriksen Governance Dr Jose Mathew Assistant Clinical Director Assistant Director of Assistant Clinical DWiraerctringor ton & Halton Operations Corporate Corporate Lorna Pink Assistant Assistant Director Julie Chadwick Vacant Clinical Director of Nursing, AHP & Associate Clinical Director Governance & Professional Warrington & Halton Compliance Standards Assistant Director of Operations Assistant Clinical Director Dr Aravind Komuravelli Halton & Warrington Knowsley Lee Bloomfield Claire Hammill Clare Dooley Berni Fay-Dunkley Assistant Director of Operations Knowsley Associate Medical Director Nicky Over Assistant Clinical Director Allied Health Knowsley Assistant Director of Sefton Professional Dr Ashish Kumar AssiOstapenrta Dtiironesc tKnor oofw Oslpeeyr ations Sara Harrison Lead Nicola Over Sefton James Hester Anne Tattersall Assistant Clinical Director Associate Clinical Director Assistant Director of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients St Helens Operations Sefton Debbie Tubey Dr Raj Madgula AssistanAt nDniree Tcatttore ofrs aOllp erations Head of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients Safeguarding Tim McPhee Assistant Clinical Director Sarah Shaw Assistant Director of Associate Medical Director Operations St Helens Mental Health -

Registration

Location Registration REGISTRATION Please register early! San Diego County Midwives Our format includes the required three hours of 15644 Pomerado Road, S-302 lactation training to assist you in completing your Name Poway, CA 92064 DONA Certification. Address 858.278.2930 Complete this registration form and submit the Parking is available in front, come right in. We full amount or a $250 deposit to reserve a spot in City/State/Zip look forward to seeing you soon! Occasionally, a the workshop (balance due by the first meeting). change of venue is necessary. Please check Registration postmarked ONE week prior to Phone emails regularly course will be only $475. Late registration (on a Email Meals, snacks, beverages space available basis) is possible, for an additional fee of $40. Profession You may bring lunches and dinner for yourself Important Cancellation Information: If (refrigerator & microwave available) or there are cancellation is received in writing by one week Any birth experiences? many eating establishments nearby. prior to workshop, a full refund less a $50.00 Payment Methods: administrative fee will be refunded. After that • Stripe, CashApp or PayPal – if you would Please bring something to share on Saturday and time, no refunds will be given; however, you may like to use this option, let Lisa know and a Sunday with your fellow doula students. designate a substitute to use your registration or request for payment will be sent to you. transfer it to another training within 1 year of the • Check/money order payable to Gerri Ryan For further information: cancelled training. can be sent to Lisa’s address below: • Lisa – 619-988-3911 call/text or Lisa Simpkins [email protected] Workshop Preparation 825 W Beech Street, #104, San Diego, CA 92101 • Gerri – I.