Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chesley Bonestell: Imagining the Future Privacy - Terms By: Don Vaughan | July 20, 2018

HOW PRINT MYDESIGNSHOP HOW DESIGN UNIVERSITY EVENTS Register Log In Search DESIGN TOPICS∠ DESIGN THEORY∠ DESIGN CULTURE∠ DAILY HELLER REGIONAL DESIGN∠ COMPETITIONS∠ EVENTS∠ JOBS∠ MAGAZINE∠ In this roundup, Print breaks down the elite group of typographers who have made lasting contributions to American type. Enter your email to download the full Enter Email article from PRINT Magazine. I'm not a robot reCAPTCHA Chesley Bonestell: Imagining the Future Privacy - Terms By: Don Vaughan | July 20, 2018 82 In 1944, Life Magazine published a series of paintings depicting Saturn as seen from its various moons. Created by a visionary artist named Chesley Bonestell, the paintings showed war-weary readers what worlds beyond our own might actually look like–a stun- ning achievement for the time. Years later, Bonestell would work closely with early space pioneers such as Willy Ley and Wernher von Braun in helping the world understand what exists beyond our tiny planet, why it is essential for us to go there, and how it could be done. Photo by Robert E. David A titan in his time, Chesley Bonestell is little remembered today except by hardcore sci- ence fiction fans and those scientists whose dreams of exploring the cosmos were first in- spired by Bonestell’s astonishingly accurate representations. However, a new documen- tary titled Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With The Future aims to introduce Bonestell to con- temporary audiences and remind the world of his remarkable accomplishments, which in- clude helping get the Golden Gate Bridge built, creating matte paintings for numerous Hol- lywood blockbusters, promoting America’s nascent space program, and more. -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme Nr. 94 (Mai 2010)

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme -Kurzübersicht- Detaillierte Informationen finden Sie auf unserer Website und in unse- rem 14tägigen Newsletter Nr. 94 (Mai 2010) LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS Talstr. 11 - 70825 Korntal Tel.: (0711) 83 21 88 - Fax: (0711) 8 38 05 18 INTERNET: www.laserhotline.de e-mail: [email protected] Katalog DVD BRD (Spielfilme) Nr. 94 Mai 2010 (500) Days of Summer 10 Dinge, die ich an dir 20009447 25,90 EUR 12 Monkeys (Remastered) 20033666 20,90 EUR hasse (Jubiläums-Edition) 20009576 25,90 EUR 20033272 20,90 EUR Der 100.000-Dollar-Fisch (K)Ein bisschen schwanger 20022334 15,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags 20032742 18,90 EUR Die 10 Gebote 20000905 25,90 EUR 20029526 20,90 EUR 1000 - Blut wird fließen! (Traum)Job gesucht - Will- 20026828 13,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags - High Noon kommen im Leben Das 10 Gebote Movie (Arthaus Premium, 2 DVDs) 20033907 20,90 EUR 20032688 15,90 EUR 1000 Dollar Kopfgeld 20024022 25,90 EUR 20034268 15,90 EUR .45 Das 10 Gebote Movie Die 120 Tage von Bottrop 20024092 22,90 EUR (Special Edition, 2 DVDs) Die 1001 Nacht Collection – 20016851 20,90 EUR 20032696 20,90 EUR Teil 1 (3 DVDs) .com for Murder 20023726 45,90 EUR 13 - Tzameti (k.J.) 20006094 15,90 EUR 10 Items or Less - Du bist 20030224 25,90 EUR wen du triffst 101 Dalmatiner (Special [Rec] (k.J.) 20024380 20,90 EUR Edition) 13 Dead Men 20027733 18,90 EUR 20003285 25,90 EUR 20028397 9,90 EUR 10 Kanus, 150 Speere und [Rec] (k.J.) drei Frauen 101 Reykjavik 13 Dead Men (k.J.) 20032991 13,90 EUR 20024742 20,90 EUR 20006974 25,90 EUR 20011131 20,90 EUR 0 Uhr 15 Zimmer 9 Die 10 Regeln der Liebe 102 Dalmatiner 13 Geister 20028243 tba 20005842 16,90 EUR 20003284 25,90 EUR 20005364 16,90 EUR 00 Schneider - Jagd auf 10 Tage die die Welt er- Das 10te Königreich (Box 13 Semester - Der frühe Nihil Baxter schütterten Set) Vogel kann mich mal 20014776 20,90 EUR 20008361 12,90 EUR 20004254 102,90 EUR 20034750 tba 08/15 Der 10. -

ALL Code Sheets

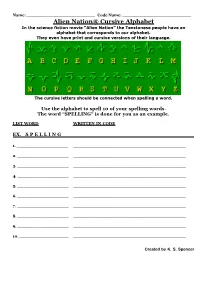

Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Cursive Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. The cursive letters should be connected when spelling a word. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD WRITTEN IN CODE EX. S P E L L I N G 1. ___________________ __________________________________________ 2. ___________________ __________________________________________ 3. ___________________ __________________________________________ 4. ___________________ __________________________________________ 5. ___________________ __________________________________________ 6. ___________________ __________________________________________ 7. ___________________ __________________________________________ 8. ___________________ __________________________________________ 9. ___________________ __________________________________________ 10. __________________ __________________________________________ Created by K. S. Spencer Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Print Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Chapter 1 1. Jeffrey Mirel, “The Traditional High School: Historical Debates over Its Nature and Function,” Education Next 6 (2006): 14–21. 2. US Census Bureau, “Education Summary––High School Gradu- ates, and College Enrollment and Degrees: 1900 to 2001,” His- torical Statistics Table HS-21, http://www.census.gov/statab/ hist/HS-21.pdf. 3. Andrew Monument, dir., Nightmares in Red, White, and Blue: The Evolution of American Horror Film (Lux Digital Pictures, 2009). 4. Monument, Nightmares in Red. Chapter 2 1. David J. Skal, Screams of Reason: Mad Science and Modern Cul- ture (New York: Norton, 1998), 18–19. For a discussion of this more complex image of the mad scientist within the context of postwar film science fiction comedies, see also Sevan Terzian and Andrew Grunzke, “Scrambled Eggheads: Ambivalent Represen- tations of Scientists in Six Hollywood Film Comedies from 1961 to 1965,” Public Understanding of Science 16 (October 2007): 407–419. 2. Esther Schor, “Frankenstein and Film,” in The Cambridge Com- panion to Mary Shelley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 63; James A. W. Heffernan, “Looking at the Monster: Frankenstein and Film,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (Autumn 1997): 136. 3. Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe (New York: Basic Books, 1987). 4. Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism and American Life (New York: Knopf, 1963); Craig Howley, Aimee Howley, and Edwine D. Pendarvis, Out of Our Minds: Anti-Intellectualism and Talent 178 Notes Development in American Schooling (New York: Teachers Col- lege Press: 1995); Merle Curti, “Intellectuals and Other People,” American Historical Review 60 (1955): 259–282. -

Frankenstein Au Cinéma

La Revue du Ciné-club universitaire, 2016, no 3 It’s alive! Frankenstein au cinéma Ciné-club UniversitaireACTIVITÉS CULTURELLES Illustration Sommaire 1ère de couverture: Frankenstein, James Whale, 1931 Histoire d’une créature fictionnelle Groupe de travail du Ciné-club universitaire Julien Dumoulin, Emilien Gür, Michel Porret et Julien Dumoulin, Emilien Gür, Cerise Dumont, Michel Porret, Olinda Testori ..................................................................... 3 Olinda Testori, Thibault Zanoni, Francisco Marzoa, Jeanne Richard Survie de la créature au cinéma Activités culturelles de l’Université Emilien Gür .........................................................................13 responsable: Ambroise Barras coordination: Christophe Campergue édition et graphisme: Véronique Wild et Julien Jespersen Quelques réflexions sur les films de Whale Julien Dumoulin ...............................................................25 L’acteur derrière le masque du monstre Francisco Marzoa .............................................................35 Le moment Hammer Michel Porret .................................................................... 41 Le laboratoire à la croisée des mondes Cerise Dumont ...................................................................59 Monstre, qui es-tu? Jeanne Richard ..................................................................65 Abnormal brain: «l’âme» déformée de la créature Thibault Zanoni ................................................................ 73 «Frankenstein» et «The Curse»: -

Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick's <Em>2001: a Space Odyssey</Em> and Andrei Tark

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-1-2010 Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky‘s Solaris Keith Cavedo University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Cavedo, Keith, "Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky‘s Solaris" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1593 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky‘s Solaris by Keith Cavedo A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Lawrence Broer, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Silvio Gaggi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 1, 2010 Keywords: Film Studies, Science Fiction Studies, Alien Identity, Human Identity © Copyright 2010, Keith Cavedo Dedication I dedicate this scholarly enterprise with all my heart to my parents, Vicki McCook Cavedo and Raymond Bernard Cavedo, Jr. for their unwavering love, support, and kindness through many difficult years. Each in their own way a lodestar, my parents have guided me to my particular destination. -

EU Page 01 COVER.Indd

JACKSONVILLE NING! OPE temples & tombs new exhibit at the cummer start planning for new year’s entertaining u newspaper INSIDE: fun events to fi nish the year free weekly guide to entertainment and more | december 21-27, 2006 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 december 21-27, 2006 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents feature New Years/Gator Bowl ..............................................................PAGES 16-19 Last Minute Gifts ............................................................................. PAGE 21 movies The History Boys (movie review) ....................................................... PAGE 6 Rocky Balboa (movie review) ............................................................ PAGE 8 Movies In Theatres This Week ....................................................PAGES 8-12 The Good Shepherd (movie review) ................................................... PAGE 9 Seen, Heard, Noted & Quoted ............................................................ PAGE 9 Charlotte’s Web (movie review) ....................................................... PAGE 10 Dreamgirls (movie review)............................................................... PAGE 11 Night At The Museum (movie review) .............................................. PAGE 12 Southeastern Film Critics Awards .................................................... PAGE 14 at home My Boys & 10 Items Or Less (TV preview) ...................................... PAGE 15 All A-Twitter (Wild Birds Unlimited)..................................................