Bamboo Management 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaster Management Plan – 2020-21

Chairman, District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Cum, Deputy Commissioner, Chikkamagaluru - 577 101 District Disaster Management Authority, Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka 08262-230401 (O), 231499 (ADC), 231222 (Fax) [email protected], deo@[email protected], [email protected] F O R E W O R D The bounty of nature with land, water, hills and so on are the beautiful creation of God which the so-called modern human beings cannot create or replicate despite advances in science and technology. The whole responsibility lies on us to maintain God's creation in its pristine state without disturbing or intervening in the ecological balance. It is observed that the more we rise in science and technology, the less we care about protecting and maintaining our environment. Indiscriminate, improper and injudicious use of environment will result in mother nature deviating from its original path and cause hazard to human life and property in the form of disasters. Chikkamagaluru district is one of the hazard prone district in Karnataka on account of landslides, drought, floods etc. The whole of the district has faced unprecedented rains in August 2019 and 2020 which has resulted in loss of human lives and destruction of property which has taught a lesson of prudence and sustainable growth to human beings. This District Disaster Management Plan devises a strategy for reducing the hazards and dangers of all kinds of disasters and accidents. It is a dedicated effort by the DDMA, Chikkamagaluru to prepare a comprehensive District Disaster Management Plan under the leadership of the District Administration. It contains the District Profile, an assessment of vulnerability and a list of possible disasters, risk assessment, the institutional and infrastructural mechanism for facing such disasters, the preparedness of the district to overcome the disasters, an effective communication plan containing the contact numbers of Officers and the standard operating procedures for effectively dealing with the disasters which are likely to occur. -

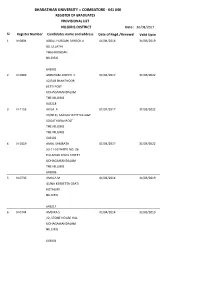

COIMBATORE - 641 046 REGISTER of GRADUATES PROVISIONAL LIST NILGIRIS DISTRICT Date : 30/08/2017 Sl

BHARATHIAR UNIVERSITY :: COIMBATORE - 641 046 REGISTER OF GRADUATES PROVISIONAL LIST NILGIRIS DISTRICT Date : 30/08/2017 Sl. Register Number Candidates name and address Date of Regd./Renewal Valid Upto 1 N-0804 ABDUL HUSSAIN FAROOK A 01/04/2014 31/03/2019 80, ULLATHI THALAKUNDAH NILGIRIS 643005 2 N-0999 ABRAHAM JOSEPH C 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 12/318 SHANTHOOR KETTI POST UDHAGAMANDALAM THE NILGIRIS 643218 3 N-1153 AKILA A 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 20/90 FI, SAKKALHATTY VILLAGE SOGATHORAI POST THE NILGIRIS THE NILGIRIS 643102 4 N-1019 AMAL SAMBATH 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 53-11-53 WARD NO: 26 PILLAIYAR KOVIL STREET UDHAGAMANDALAM THE NILGIRIS 643006 5 N-0736 AMALA M 01/04/2014 31/03/2019 45/NA KERBETTA OSATI KOTAGIRI NILGIRIS 643217 6 N-0744 AMBIKA S 01/04/2014 31/03/2019 22, STONE HOUSE HILL UDHAGAMANDALAM NILGIRIS 643001 BHARATHIAR UNIVERSITY :: COIMBATORE - 641 046 REGISTER OF GRADUATES PROVISIONAL LIST NILGIRIS DISTRICT Date : 30/08/2017 Sl. Register Number Candidates name and address Date of Regd./Renewal Valid Upto 7 N-1240 AMUDESHWARAN A 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 12/40 A1A, ATHIPALLY ROAD KALAMBUZHA GUDALUR THE NILGIRIS 643212 8 N-0750 ANAND S 01/04/2014 31/03/2019 KOOKAL VILL &PO OOTY NILGIRIS 9 N-1008 ANANDARAJ R 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 3/239 B, KADANAD VILLAGE & POST GUDALUR THE NILGIRIS THE NILGIRIS 643206 10 N-1073 ANITHA D 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 18/65 KALLIMARA EPPANADU OOTY THE NILGIRIS 643006 11 N-1246 ANITHA P K 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 1143/6 MARIAMMAN AVENUE, C1 ESTATE, ARUVANKADU, COONOOR, THE NILGIRIS 643202 12 N-1156 ANTIHA A 01/04/2017 31/03/2022 1/191 AARUVA HOSSATTY NADUHATTY KATTABETTU THE NILGIRIS 643214 BHARATHIAR UNIVERSITY :: COIMBATORE - 641 046 REGISTER OF GRADUATES PROVISIONAL LIST NILGIRIS DISTRICT Date : 30/08/2017 Sl. -

International Journal for Scientific Research & Development

IJSRD - International Journal for Scientific Research & Development| Vol. 3, Issue 11, 2016 | ISSN (online): 2321-0613 Landslide Susceptibility Zonation in Kallar Halla, Upper Coonoor, Lower Coonoor, Upper Katteri and Lower Katteri Watershed in Part of Nilgiris District, Tami Nadu,India using Remote Sensing and GIL Backiaraj S1 Ram MohanV2 Ramamoorthy P3 1,2,3Department of Geology 1,2University of Madras, Guindy Campus, Chennai - 600 025, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract— Landslides play an important role in the were grown and the death toll was 4 due to a 1 km long evolution of landforms and represent a serious hazard in debris slide in Selas near Ketti. Settlements where less many areas of the World. In places, fatalities and economic damaged as they were in safe zones. Since, 1978-79, the damage caused by landslides are larger than those caused by frequency of landslides has increased and the landslide other natural hazards, including earthquakes, volcanic during October, 1990, buried more than 35 families in a eruptions and floods. The Nilgiris district is located in the place called Geddai and in 1993, the landslide in southern state of Tamilnadu in India, bounded on the north Marappalam killed 12 persons, 15 were reported missing by the state of Karnataka, on the east by Coimbatore and and 21 persons were killed when two busses were washed Erode districts, on the south by Coimbatore district and on away down steep slopes (Ganapathy, Hada, 2012). In 2009, the west by the state of Kerala. Although most parts of heavy rains resulted in the death of 42 persons. -

District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP)

District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) FOR CHIKKAMAGALURU DISTRICT 2019-20 Approved by: Chairman, District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Cum. Deputy Commissioner Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Preparerd by: District Disaster Management Authority Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Ph: 08262-230401(O); 231499 (ADC); 231222 (Fax) e.mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 1 P R E F A C E Chikkamagaluru district is a district with varied climatic and geographic conditions. While part of the district falls in the Malnad region, another part falls in the plain lands. Therefore the problems faced by these areas may also be different and diverse. Due to unlimited human intervention with nature and exploitation of nature, the frequency and probability of the disasters and accidents have increased drastically in the recent times. The heavy rains of August 2019 has taught the Administration to be alert and prepared for such type of disasters which are unforeseen. On the one hand heavy rains may cause floods, water logging and intense landslides, there may also be situations of drought and famine. In view of this the district has to be ready and gear itself up to meet any situation of emergency that may occur. The District Disaster Management Plan is the key for management of any emergency or disaster as the effects of unexpected disasters can be effectively addressed. This plan has been prepared based on the experiences of the past in the management of various disasters that have occurred in the district. This plan contains the blue print of the precautionary measures that need to be taken for the prevention of such disasters as well as the steps that have to be taken for ensuring that the human suffering and misery is reduced by appropriate and timely actions in rescuing the affected persons, shifting them to safer places and providing them with timely medical care and attention. -

Women's Participation and MGNREGP with Special Reference to Coonoor in Nilgiris District: Issues and Challenges

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Women’s Participation and MGNREGP with Special Reference to Coonoor in Nilgiris District: Issues and Challenges C, Dr. Jeeva Providence College for Women, Coonoor, Tamilnadu, India December 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/107315/ MPRA Paper No. 107315, posted 02 Jun 2021 14:12 UTC WOMEN’S PARTICIPATION AND MGNREGP WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO COONOOR IN NILGIRIS DISTRICT: ISSUES AND CHALLENGES Mrs. C.JEEVA. MA, M.Phil.NET Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Providence College for Women, Coonoor, Tamilnadu, India Email. [email protected], contact No. 9489524836 ABSTRACT: The MGNREGA 2005, plays a significant role to meet the practical as well as strategic needs of women’s participation. It is a self –targeting programme, intended in increasing outreach to the poor and marginalized sections of the society such as women and helping them towards the cause of financial and economic inclusion in the society. In the rural milieu, it promises employment opportunities for women and their empowerment. While their hardships have been reduced due to developmental projects carried out in rural areas, self-earnings have improved their status to a certain extent. However, women’s decision for participation and their share in MNREGP jobs is hindered by various factors. Apart from some structural problems, inattentiveness and improper implementation of scheme, social attitudes, exploitation and corruption have put question marks over the intents of the programme. At this juncture, the litmus test of the policy will have an impact on the entire process of rural development and women employment opportunities in India. There is excitement as well as disappointment over the implementation on the Act. -

District Statistical Handbook 2018-19

DISTRICT STATISTICAL HANDBOOK 2018-19 DINDIGUL DISTRICT DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF STATISTICS DISTRICT STATISTICS OFFICE DINDIGUL Our Sincere thanks to Thiru.Atul Anand, I.A.S. Commissioner Department of Economics and Statistics Chennai Tmt. M.Vijayalakshmi, I.A.S District Collector, Dindigul With the Guidance of Thiru.K.Jayasankar M.A., Regional Joint Director of Statistics (FAC) Madurai Team of Official Thiru.N.Karuppaiah M.Sc., B.Ed., M.C.A., Deputy Director of Statistics, Dindigul Thiru.D.Shunmuganaathan M.Sc, PBDCSA., Divisional Assistant Director of Statistics, Kodaikanal Tmt. N.Girija, MA. Statistical Officer (Admn.), Dindigul Thiru.S.R.Arulkamatchi, MA. Statistical Officer (Scheme), Dindigul. Tmt. P.Padmapooshanam, M.Sc,B.Ed. Statistical Officer (Computer), Dindigul Selvi.V.Nagalakshmi, M.Sc,B.Ed,M.Phil. Assistant Statistical Investigator (HQ), Dindigul DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK 2018-19 PREFACE Stimulated by the chief aim of presenting an authentic and overall picture of the socio-economic variables of Dindigul District. The District Statistical Handbook for the year 2018-19 has been prepared by the Department of Economics and Statistics. Being a fruitful resource document. It will meet the multiple and vast data needs of the Government and stakeholders in the context of planning, decision making and formulation of developmental policies. The wide range of valid information in the book covers the key indicators of demography, agricultural and non-agricultural sectors of the District economy. The worthy data with adequacy and accuracy provided in the Hand Book would be immensely vital in monitoring the district functions and devising need based developmental strategies. It is truly significant to observe that comparative and time series data have been provided in the appropriate tables in view of rendering an aerial view to the discerning stakeholding readers. -

Feasibility Studies of New Ghat Road Project Chainage 50+050 to Chainage 55+290 in the State of Maharashtra

ISSN (Online): 2455-366 EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR) - Peer Reviewed Journal Volume: 6 | Issue: 7 | July 2020 || Journal DOI: 10.36713/epra2013 || SJIF Impact Factor: 7.032 ||ISI Value: 1.188 FEASIBILITY STUDIES OF NEW GHAT ROAD PROJECT CHAINAGE 50+050 TO CHAINAGE 55+290 IN THE STATE OF MAHARASHTRA Sahil S. Shinde1 Tushar R. Bagul2 1PG Student, 2Assistant Professor, Civil Department (C&M), Civil Department (C&M), Dr. D.Y. Patil College of Engineering, Dr. D.Y. Patil College of Engineering, Pune, Pune, India India ABSTRACT Feasibility studies are carried out to validate expenditure on infrastructure projects. In spite the importance of the studies in supporting decisions related to public expenditure on infrastructure projects, there are no attempts to assess such studies after construction. Ghat Roads are approach routes into the mountainous region like Western and Eastern Ghats. They generally served to connect to sea side regions with the upper region Deccan plateau of the Indian Subcontinent. An analysis of a feasibility study for a state highway ghat road construction project is presented in this paper with an emphasis on the estimates, and forecasts presented in that study to weigh expected benefits from the project against expected costs. The Ghat road will improve connectivity between two tahsils, reducing the travel distance by 40.00 KMS. The Proposed road aims to reduce the Distance and travel time between two districts. This would facilitate trade, and commerce between two districts and reduce the traffic pressure on present roads passing through the existing ghats which are used to travel in kokan presently. -

Orissa Review

ORISSA REVIEW VOL. LXVII NO. 11 JUNE - 2011 SURENDRA NATH TRIPATHI, I.A.S. Principal Secretary BAISHNAB PRASAD MOHANTY Director-cum-Joint Secretary LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Bikram Maharana Production Assistance Debasis Pattnaik Sadhana Mishra Manas R. Nayak Cover Design & Illustration Hemanta Kumar Sahoo D.T.P. & Design Raju Singh Manas Ranjan Mohanty Photo The Orissa Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Orissa’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Orissa Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Orissa. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Orissa, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Orissa Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Visit : http://orissa.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shree Shree Jagannathastakam Shri Shankaracharya ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 10 Indian Culture Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Celebration of Raja: True Manifestation of Woman Empowerment Bikram Maharana ... 18 The Role of FDI in Economic Growth : A Study Dr. Rashmita Sahoo About Odisha Soumendra Patra ... 20 Black Soils of Orissa and their Management Dr. Antaryami Mishra, Dr. B.B.Dash & D. Das ... 24 Malkangiri — The Treasure of Tribal Tourism and Culture Dasharathi Patra ... 27 Odisha and Climate Change Action Plan Gurukalyan Mohapatra ... 32 Development and Cultural Change Among the Kandh Tribals of Kandhamal Raghunath Rath ... 34 NGOs and the Development of the Tribal People – A Case Study of Keonjhar District Subhrabala Behera .. -

Fraser Odonata3

THE FAUNA OF BRITISH INDIA, INCLnDINS CEYLON AND BURMA PUBUSHKI) riKOBll THE AOTHOUITY OF THM SBCItETARY OF Statu: Fon Tnuta rN OoutfciL. EDITED BT LT.-COL. B. B. S. SEWELI,, C.I.E., So.D., P.E.S., I.M.8. (reL). ODONATA. VOL, III. Lt.-Col. F. C. eraser, I,M S. (Ret.). TAYLOR AND PEANCIS, LTD., RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET, LONDON, E.G. 4, 21«JZ>ece»i&er, 1936. PBINTED BY TAYLOE AND FEANCIS, LTD., BBD tlOK QOVB.T, PUSET STREET. CONTENTS. Page Peeface T Addenda BT CoBEiGENDA TO Volumes I-III. ... vii Systematic Index ix Anisopteba (continued) 1 Cordulegasteridae 1 CMorogomphinse 3 Cordulegasterinse 28 ^shnidse 53 LibeUuUdse 156 Corduliinse 158 LibeUulinse 240 Alphabetical Index 463 PREFAGE. ' The first volume of The Tauna of British India ' dealing with the Order Odonata was published in 1933, and dealt with the first family of the Zygoptbra ; the second volume, pubhshed in 1934, completed the Zy&OPTESA, and dealt with the Gomphidse, or first family of the Anisoptera. In this volume the remaining three famiHes of the Anisoptbea— the Cordulegasteridje, ^shnidss, and LibeUuUdse—are dealt with, and 197 further species are described, inoludiag one which was omitted by oversight in Volume I, bringiog the total number found within our faunal limits up to 537. That we have not yet exhausted the full number of species to be found appears probable from the fact that new ones continued to be found whilst this book was in course of preparation. It is certain that new species will be found along the eastern frontiers of Burma and Assam, this area not having been worked at all for Odonata, and bordering on one of the richest faunal areas of the world. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2010 [Price: Rs. 19.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 20] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MAY 26, 2010 Vaikasi 12, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 875-921 Notice .. 873 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES I, Rashidhsabi, wife of Thiru B. Fakhruddin, born My son, R. Umesh, born on 18th January 1997 on 9th September 1970 (native district: Chinnai), residing at (native district: Chennai), residing at Old No. 13, New No. 3, No. 15, Angappa Naicken Street, Mannady, Chennai- Rekha Nagar Main Road, Madhavaram Milk Colony, 600 001, shall henceforth be known as RASHIDHA, F. Chennai-600 051, shall henceforth be known RASHIDHSABI. as C.R. UMESHADHITHYA. Chennai, 17th May 2010. D. RATTHNAKUMAR. Chennai, 17th May 2010. (Father.) My son, S. Dineshkumaran, born on 26th September 2006 (native district: Erode), residing at No. 37-A, I, J. Meena, wife of Thiru T. Jeyamkondaan, born on Palaniappa Cross II, Thavittupalayam, Anthiyur Post, Erode- 31st May 1966 (native district: Pudukkottai), residing at 638 501, shall henceforth be known as K.S. DINESHPRANAV. Old No. 30, New No. 14, East Second Street, K.K. Nagar, Madurai-625 020, shall henceforth be known as J. -

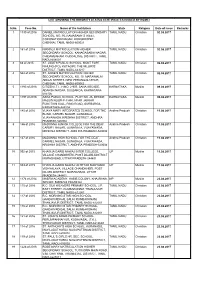

S.No. Case No. Name of the Institution State Religion Date of Issue

LIST SHOWING THE MINORITY STATUS CERTIFICATES ISSUED BY NCMEI S.No. Case No. Name of the Institution State Religion Date of Issue Remarks 1 1330 of 2016 DANIEL MATRICULATION HIGHER SECONDARY TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 SCHOOL, NO. 36, RAMASAMY STREET, CORONATION NAGAR, KORUKKUPET, CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU-600021 2 161 of 2016 NIRMALA MATRICULATION HIGHER TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 SECONDARY SCHOOL, KANAGASABAI NAGAR, CHIDAMBARAM, CUDDALORE DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU-608001 3 68 of 2015 ST. JUDE’S PUBLIC SCHOOL, MONT FORT, TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 NIHUNG (PO), KOTAGIRI, THE NILGIRIS DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU-643217 4 544 of 2016 ST. ANNE’S MATRICULATION HIGHER TAMIL NADU Christian 02.08.2017 SECONDARY SCHOOL, NO. 10, MARAIMALAI ADIGAI STREET, NEW PERUNGALATHUR, CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU-600063 5 1193 of 2016 CITIZEN I.T.I., H.NO. 2-907, SANA ARCADE, KARNATAKA Muslim 09.08.2017 ADARSH NAGAR, GULBARGA, KARNATAKA- 585105 6 1197 of 2016 ASRA PUBLIC SCHOOL, PLOT NO. 26, BESIDE KARNATAKA Muslim 09.08.2017 MASJID NOOR-E-ILAHI, NEAR JABBAR FUNCTION HALL, RING ROAD, GURBARGA, KARNATAKA-585104 7 145 of 2016 VIJAYA MARY INTEGRATED SCHOOL FOR THE Andhra Pradesh Christian 11.08.2017 BLIND, CARMEL NAGAR, GUNADALA, VIJAYAWADA, KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH-520004 8 146 of 2016 MADONNA JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR THE DEAF, Andhra Pradesh Christian 11.08.2017 CARMEL NAGAR, GUNADALA, VIJAYAWADA, KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH-520004 9 147 of 2016 MADONNA HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE DEAF, Andhra Pradesh Christian 11.08.2017 CARMEL NAGAR, GUNADALA, VIJAYAWADA, KRISHNA DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH-520004 10 992 of 2015 KHAWJA GARIB NAWAJ INTER COLLEGE, UP Muslim 11.08.2017 VILLAGE CHANDKHERI, POST DILARI, DISTRICT MORADABAD, UTTAR PRADESH-244401 11 993 of 2015 KHAWJA GARIB NAWAJ UCHTTAR MADYAMIK UP Muslim 11.08.2017 VIDHYALAYA, VILLAGE CHANDKHERI, POST DILARI, DISTRICT MORADABAD, UTTAR PRADESH-244401 12 1174 of 2014 MABFM ACADEMY, HABIB COLONY, KHAJRANA, MP Muslim 23.08.2017 INDORE, MADHYA PRADESH 13 115 of 2016 R.C. -

Easychair Preprint Safety in Ghat Section Using Rolling Barrier

EasyChair Preprint № 2827 Safety in Ghat Section using Rolling Barrier Sohail Khan and Soham Bhagwat EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. March 3, 2020 National Conference on "Role of Engineers in Nation Building" organized by VIVA Institute of Technology, Mumbai (6th and 7th March 2020) International Journal of Engineering Research & Science (IJOER) ISBN:[ 978-93-5391-287-1] ISSN: [2395-6992] [Vol-5, Issue-3, March- 2020] Safety in Ghat Section using Rolling Barrier 1Khan Sohail, 2Bhagwat Soham 1Department of civil engineering, Mumbai university, Mumbai [email protected] 2Department of civil engineering, Mumbai university, Mumbai [email protected] Abstract— This paper highlights on the need for cost effective road safety investments using 'rolling barrier' systems which can redirect the deviated automobiles onto the right path and also prevent the overturning of vehicles. The Road accidents are an outcome of the interplay of various factors, some of which are length of road networks, vehicle population, in case of our paper the topography of ghats and curvature of turns also plays a part along with human population adherence/enforcement of road safety regulations etc. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the Rolling Barrier and to understand the Rolling Barrier‟s characteristics of crash cushioning. The Rolling Barrier can be effectively used in curved roads sections as seen in various test done on performance of Rolling Barriers. Keywords—Hairbend turns, Ghat Roads, Barriers, Rolling Barriers, Shock absorbent Barriers. I. INTRODUCTION Most of the ghat roads in Maharashtra exist in Sahyadri ranges.