ARTICLE Justice Rabinowitz and Personal Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGAGED PRACTICE PLAN OPENS DOORS for STUDENT ARTISTS New Requirement Helps Bring Their Work Into the World

Founded in 1882, Cleveland Institute of Art is an independent college of art and design committed to leadership and vision in all forms of visual arts education. CIA makes enduring contributions to art and education and connects to the community through gallery exhibitions, lectures, a continuing education program and Link the Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque. FALL 2016 NEWS FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF ART ENGAGED PRACTICE PLAN OPENS DOORS FOR STUDENT ARTISTS New requirement helps bring their work into the world Classrooms and studios are an art comes in,” Whittey says. “Students go out “Students go out into the world, more bubbly and happy,” Brantley says. student’s best friends, but nothing into the world, meet with people they’ve “With another person, he had a very strong broadens perspective like field learning. never met with before, work for them, meet with people they’ve personality, so I drew him in a very dramatic With that in mind, CIA academic leaders work with them, and do problem solving never met with before, work setting so that would come across. Then I this fall introduced a new measure to together. They learn how to be professional, made his facial features a little stronger.” ensure that students earn at least three however they define that.” for them, work with them, and Brantley brings away from the course Engaged Practice credits by graduation. For more than 20 years, CIA’s Industrial some practical lessons, like scheduling The requirement will give them experience Design students have worked with teams at do problem solving together.” visits and working within a medical working with a range of professional Fisher Price and Little Tikes to gain experi- environment. -

Shelter from the Storm: the Case for Guaranteed Income

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAY|JUN21 GAZETTE Shelter from the Storm: The Case for Guaranteed Income The Long Road to mRNA Vaccines Memoirs for All Ages Virtual Healthcare Gets Real DIGITAL + IPAD The Pennsylvania Gazette DIGITAL EDITION is an exact replica of the print copy in electronic form. Readers can download the magazine as a PDF or view it on an Internet browser from their desktop computer or laptop. And now the Digital Gazette is available through an iPad app, too. THEPENNGAZETTE.COM/DIGIGAZ Digigaz_FullPage.indd 4 12/22/20 11:52 AM THE PENNSYLVANIA Features GAZETTE MAY|JUN21 Fighting Poverty The Vaccine Trenches with Cash Key breakthroughs leading to the Several decades since the last powerful mRNA vaccines against big income experiment was 42 COVID-19 were forged at Penn. 34 conducted in the US, School of That triumph was almost 50 years in the Social Policy & Practice assistant making, longer on obstacles than professor Amy Castro Baker has helped celebration, and the COVID-19 vaccines deliver promising data out of Stockton, may only be the beginning of its impact on California, about the effects of giving 21st-century medicine. By Matthew De George people no-strings-attached money every month. Now boosted by a new research center at Penn that she’ll colead, more Webside Manner cities are jumping on board to see if Virtual healthcare by smartphone guaranteed income can lift their residents or computer helps physicians out of poverty. Will it work? And will 50 consult with and diagnose patients policymakers listen? much more quickly, while offering them By Dave Zeitlin convenience and fl exibility. -

House Votes $70 Million for El Salvador

Tax platform divides Mrs. Chaves,-81, Decker’s stumble GOP planning committee still avid bowler Is a costly one ... page 4 ... page 11 ... page 15 Mostly cloudy; Manchester, Conn. chance of showers Saturday. August 11. 1984 — See page 2 iiattrliralpr Hrralh Single copy: 25C: House votes $70 million for El Salvador By Robert Shepard dispute that threatened passage of issue back to the House for another give democracy a chance." fiscal year ending Sept. 30, The two lesser amount. United Press International the $6.2 billion supplemental vote. Speaker Thomas O'Neill, who houses were about $2 billion apart A $90 million compromise was spending bill needed to keep most Rep. Clarence Long, D-Md., continued to oppose the aid, said in their original versions of the bill, offered during the conference if WASHINGTON - The House government agencies operating chairman of the House Appropria earlier Friday the House probably but the confehutee committee committee meeting Thursday abandoned its opposition to more until the end of the fiscalyearSept. tions subcommittee on foreign would agree to a compromise came up with a $5.8 billion night, but was rejected by most of military aid for El Salvador this 30. operations who originally opposed figure. compromise on the non-aid the majority Democrats oh the year and voted Friday for $70 The action also cleared the way any additional aid, eased his O'Neill said that since the provisions. panel. A $70 million offer also was million of the $117 million sought for Congress to recess until after position and offered an amend previous House vote some key The most urgent item was $700 rejected. -

A Revolt in the Ranks: the Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight*

ARTICLES A Revolt in the Ranks: The Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight* PAMELA CRAVEZ** This Article details the post-statehood controversy between the Alaska Supreme Court and the Alaska Bar Association known as the "court-barfight." First,the Article discusses United States v. Stringer, a 1954 attorney discipline case illustrating the territorial courts' perceived inability to regulate adequately the legal Copyright © 1996 by Alaska Law Review * This article is excerpted from Pamela Cravez, Seizing the Frontier, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers (1984) (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). The author would like to thank Professor Thomas West of Catholic University for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and Jeffrey Mayhook for his insightful editing. She would also like to thank Senior U.S. District Court Judge James M. Fitzgerald, Anchorage District Court Judge James Wanamaker, Glenn Cravez, Joyce Bamberger, Averil Lerman and Patsy Romack for their careful reviews and the Anchorage Bar Association for its generous support of Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History. Editor's note: The author has drawn much of the material for this article from Anchorage Bar Ass'n, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History, an unpublished series of taperecorded interviews commissioned by the Anchorage Bar Association and conducted by the author. The audiocassettes are located at the former U.S. District Courthouse in Anchorage, Alaska. Unless otherwise indicated by citation, the information and quotations in this article have been drawn from this source. The editors, however, have not independently verified the information derived from the oral history. Accordingly, we rely on the author's representations as to the authenticity and accuracy of the statements drawn therefrom. -

Document Resume

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 352 222 RC 018 866 TITLE Alaskan Rural Justice: A Selected Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION Alaska Judicial Council, Anchorage. PUB DATE May 91 NOTE 170p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alaska Natives; Alcohol Abuse; American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; *Courts; Crime; Eskimos; *Justice; *Law Enforcement; *Local Government; *Rural Areas; Self Determination IDENTIFIERS *Alaska; Tribal Government ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography lists approximately 300 documents and source materials directly or indirectly related to the problem of access to justice in rural Alaska. Written materials about the state's history, geography, economics, and culture have often touched upon the justice system and its role in the development of the state. Other works have focused specifically on the courts and law enforcement, detailing the problems created by resource allocation, political exigencies, and commingling of cultures. This bibliography includes annotations for books, articles, reports, letters, agency records, diaries, and films. Entries are categorized under: agency and commission reports; alcohol abuse and treatment; alternate dispute resolutions (tribal courts, judgment boards, and village councils); anthropological, cultural, and sociological studies; bibliographies and source materials; Bush Justice Conference reports; Canadian rural justice; children, families, and the Indian Child Welfare Act; grand jury reports; health, -

South Atrium Expansion Northwestern Law's $150 Million Campaign

THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW VOLUME III NUMBER 2 SUMMER 2015 South Atrium Expansion Northwestern Law’s $150 Million Campaign Access to Health Tackles Global Challenges NORTHWESTERN LAW REPORTER Summer 2015, Volume III, Number 2 DEAN AND HAROLD WASHINGTON PROFESSOR Daniel B. Rodriguez ASSOCIATE DEAN OF ENROLLMENT, CAREER STRATEGY, AND MARKETING Donald L. Rebstock ASSISTANT DEAN OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kirston Fortune DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS Darnell Hines DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kathleen Gleeson SENIOR DESIGNER Mary Kate Radelet CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Hilary Hurd Anyaso Kirston Fortune Kathleen Gleeson Rekha Radhakrishnan Pat Vaughan Tremmel Amy Weiss CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Randy Belice Teresa Crawford Northwestern Law Facilities Roy Scott/Illustration Source Jasmin Shah The editors thank the faculty, staff, students, and alumni of Northwestern University School of Law for their cooperation in this publication. Opinions expressed in the Northwestern Law Reporter do not necessarily reflect the views of Northwestern University School of Law or Northwestern University. Update Your Address EMAIL [email protected] WEB law.alumni.northwestern.edu PHONE 312.503.7609 US MAIL Northwestern University School of Law Office of Alumni Relations and Development 375 East Chicago Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60611 Find us online at law.northwestern.edu Copyright ©2015. Northwestern University School of Law. All rights reserved. 7-15/16M THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW VOLUME III NUMBER 2 SUMMER 2015 6 14 46 34 FEATURES 16 Motion to Lead: The Campaign for Northwestern Law 22 Northwestern Law’s ambitious $150 million fundraising effort aims to fuel innovation and foster creative solutions to the myriad challenges of the ever-evolving legal environment. -

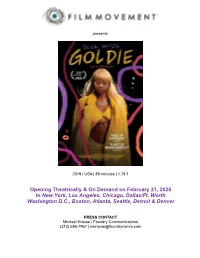

Opening Theatrically & on Demand on February 21, 2020 in New York

presents 2019 | USA | 88 minutes | 1.78:1 Opening Theatrically & On Demand on February 21, 2020 In New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas/Ft. Worth Washington D.C., Boston, Atlanta, Seattle, Detroit & Denver PRESS CONTACT Michael Krause | Foundry Communications (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Synopsis Not even the vibrant streets of the Bronx can contain Goldie (Slick Woods), a street- wise 18-year-old whose intoxicating dreams of fame – and the better life she believes it will bring for herself and her family – are all but contagious. But it’s only when Goldie’s dreams collide with the harsh realities of her world that she discovers her true strength in writer/director Sam de Jong’s bittersweet coming-of-age story. Though she may live in a shelter, sharing a single room with her mother, Carol (Marsha Stephanie Blake), her partner Frank (Danny Hoch) and kid-sisters Sherrie, 8, and Supreme, 12 (Alanna Renee Tyler-Tompkins and Jazmyn C. Dorsey), Goldie’s dream of a better life is not only palatable, but seems to sustain those closest to her. An enthusiastic dancer who enjoys performing on the community center’s makeshift stage, she is offered a chance by the well-connected Jay (Khris Davis) to submit an audition tape to local-legend, Tiny (A$AP Ferg), a rapper planning to shoot a music video that weekend. Inspired by the prospect, bristling with attitude and a winsome gap-toothed style all her own (and now pocketing $300 she’s lifted from the shady, Frank), Goldie’s plan is simple – get the additional $300 needed to purchase the canary yellow fur coat on display at a local store to complete her look for her screen debut, and fulfill her destiny. -

The Ineffectiveness of the Rules Governing Judicial Campaign Speech

1-1-1999 Gagged but not Bound: The Ineffectiveness of the Rules Governing Judicial Campaign Speech Max J. Minzner University of New Mexico - School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Max J. Minzner, Gagged but not Bound: The Ineffectiveness of the Rules Governing Judicial Campaign Speech, 68 UMKC Law Review 209 (1999). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship/479 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNM School of Law at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. GAGGED BUT NOT BOUND: THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF THE RULES GOVERNING JUDICIAL CAMPAIGN SPEECH Max Minzner* JOHN DIXON DOESN'T THINK 20 STAB WOUNDS ARE ENOUGH .... On appeal to the Louisiana Supreme Court, six Justices agreed with the death sentence. ONLY JOHN DIXON DIDN'T .... HE DIDN'T THINK MORE THAN 20 TIMES WAS ENOUGH TO JUSTIFY THE DEATH PENALTY WHAT ABOUT YOU? THERE COMES A TIME TO DRAW THE LINE. THE TIME IS NOW.' Justice John Dixon's opponent ran this ad in a 1984 race for the Louisi- 2 ana Supreme Court. A large dagger was printed next to the advertisement. Jay B. Mallot, Jr Raped a Three Year Old Girl. He was found guilty and given 15 years in prison .... But--the story isn't over. One of Alaska's Supreme Court Justices, Jay Rabinowitz, tried to reduce his sentence. -

Law Library Journal

Vol. 110, No. 3 “A must for academic and law-school libraries. Summer 2018 . A treasure trove of information for those who teach or practice church-state law.” —Voice of Reason JOURNAL LIBRARY LAW RELIGIOUS LIBERTY LAW Douglas LaYcock “Any person who cares LIBRARY about religious liberty in America (and we should JOURNAL all be greatly concerned about its increasingly fragile condition) needs Vol. 110, No. 3 Summer 2018 Pages 301–440 110, No. 3 Summer 2018 Pages Vol. to read Douglas Laycock.” ARTICLES District Court Opinions That Remain Hidden Despite a Long-standing Congressional Mandate of Transparency—The Result of Judicial —Kim Colby, Center for Law Autonomy and Systemic Indifference [2018-14] and Religious Freedom Peter W. Martin 305 Sources of Alaska Legal History: An Annotated Each individual volume and Bibliography, Part I [2018-15] complete five-volume set W. Clinton “Buck” Sterling 333 AVAILABLE NOVEMBER 2018 Volume 1: Overviews and History (9780802864659) Volume 2: The Free Exercise Clause (9780802865229) Volume 3: Religious Freedom Restoration Acts, Same-Sex Marriage Legislation, and the Culture Wars (9780802876058) Volume 4: Federal Legislation after the Religious Freedom Legislation Acts, with More on the Culture Wars (9780802876065) Volume 5: The Free Speech and Establishment Clauses (9780802876157) Five Volume Set: (9780802876904) Wherever books are sold. 0023-9283(201822)110:3;1-G The authoritative voice on case law from across the pond. The Law Reports and The Weekly Law Reports, along with ICLR’s other authoritative series of law reports, are now exclusively available at iclr.co.uk. So, if your library ever fields requests for English case law, we suggest you take a look. -

Alaska Court System Annual Report FY 2019: July 1, 2018 – June 30

Alaska Court System Annual Report FY 2019 July 1, 2018 = June 30, 2019 . • - ..- -- Alaska Court Locations, FY 2019 Utqiagvik Second Judicial District / Pt. Hope •I-._ \ Kotzebue Fort Yukon Fourth Judicial District Nome Fairbanks Galena• Unalakleet Nenana • • • Delta Junction Tok Emmonak • Hooper Bay Palmer Glennallen Aniak Bethel Anchorage Valdez Kenai Cordova Yakutat Skagway Seward Haines Dillingham Homer Juneau Naknek Hoonah St. Paul Third Judicial District • Angoon Sitka Petersburg Kodiak Wrangell Kake Prince of Wales Ketchikan First Judicial District Sand Point Unalaska Front matter Cover page 303 K STREET ANCHORAGE, ALASKA 99501 CHRISTINE E. JOHNSON (907) 264-0548 Administrative Director FAX (907) 264-0881 The Alaska Court System is pleased to present its FY 2019 annual report. As in previous years, we have designed the report to serve as a reference source for all concerned with the administration of justice in Alaska — legislators and other government officials, researchers, the media, and the general public. The report presents statistical data on court activity, summary budget information, and a review of technological developments. The names and photographs of all the judicial officers and primary court administrators who served during FY19 are also included, along with maps showing court locations in the four judicial districts. We provide an overview of court administrative functions, including programs and initiatives that have involved partnerships with the other branches of state government. The court system uses public resources for its operations. We reiterate our commitment to careful management of these resources and believe that this report gives a picture of our stewardship. As I hope this annual report reflects, our state court system is committed to ensuring that all who come into the stateʼs courts receive fair and considered attention. -

A Revolt in the Ranks: the Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight*

ARTICLES A Revolt in the Ranks: The Great Alaska Court-Bar Fight* PAMELA CRAVEZ** This Article details the post-statehood controversy between the Alaska Supreme Court and the Alaska Bar Association known as the "court-barfight." First,the Article discusses United States v. Stringer, a 1954 attorney discipline case illustrating the territorial courts' perceived inability to regulate adequately the legal Copyright © 1996 by Alaska Law Review * This article is excerpted from Pamela Cravez, Seizing the Frontier, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers (1984) (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). The author would like to thank Professor Thomas West of Catholic University for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and Jeffrey Mayhook for his insightful editing. She would also like to thank Senior U.S. District Court Judge James M. Fitzgerald, Anchorage District Court Judge James Wanamaker, Glenn Cravez, Joyce Bamberger, Averil Lerman and Patsy Romack for their careful reviews and the Anchorage Bar Association for its generous support of Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History. Editor's note: The author has drawn much of the material for this article from Anchorage Bar Ass'n, Alaska's Territorial Lawyers: An Oral History, an unpublished series of taperecorded interviews commissioned by the Anchorage Bar Association and conducted by the author. The audiocassettes are located at the former U.S. District Courthouse in Anchorage, Alaska. Unless otherwise indicated by citation, the information and quotations in this article have been drawn from this source. The editors, however, have not independently verified the information derived from the oral history. Accordingly, we rely on the author's representations as to the authenticity and accuracy of the statements drawn therefrom. -

Reforming the Law of Evidence of Tanzania

THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW VOLUME III NUMBER 1 FALL 2014 Reforming the Law of Evidence of Tanzania The Importance of Death Penalty Litigation New Research Faculty LLM Alumni in International Human Rights NORTHWESTERN LAW REPORTER Fall 2014, Volume III, Number 1 DEAN AND HAROLD WASHINGTON PROFESSOR Daniel B. Rodriguez ASSOCIATE DEAN OF ENROLLMENT, CAREER STRATEGY, AND MARKETING Donald L. Rebstock ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNI RELATIONS Jaci Thiede ASSISTANT DEAN OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kirston Fortune DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS Julie Chin DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kathleen Gleeson SENIOR DESIGNER Mary Kate Radelet CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Abby Boyle, Kirston Fortune, Kathleen Gleeson, Jennifer West CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Katherine Allison (JD ’14), Randy Belice, Teresa Crawford, Dalton C. DeHart, Tom LeGoff, Dimitri Rizek (JD ’15), Jasmin Shah, Vincent van Zeijst Photos of the BPI Annual Dinner on page 20 by Timmy Samuel. Photo on page 44 by Robert Newcomb, courtesy of the University of Georgia. The editors thank the faculty, staff, students, and alumni of Northwestern University School of Law for their cooperation in this publication. Opinions expressed in the Northwestern Law Reporter do not necessarily reflect the views of Northwestern University School of Law or Northwestern University. Update Your Address EMAIL [email protected] WEB law.alumni.northwestern.edu PHONE 312.503.7609 US MAIL Northwestern University School of Law Office of Alumni Relations and Development 375 East Chicago Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60611 Find us online at www.law.northwestern.edu Copyright ©2014. Northwestern University School of Law. All rights reserved. 9-14/16M Right: The construction crew renovates the second floor of the Rubloff Building, outside the entrance to the Pritzker Legal Research Center, as part of the Law School’s Atrium expansion project scheduled for completion in spring 2015.