Arxiv:1704.06661V1 [Astro-Ph.CO]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery of Extended Radio Emission in the Merging Galaxy Cluster Abell 2146.', Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society., 475 (2)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 29 March 2018 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hlavacek-Larrondo, J. and Gendron-Marsolais, M.-L. and Fecteau-Beaucage, D. and van Weeren, R. J. and Russell, H. R. and Edge, A. and Olamaie, M. and Rumsey, C. and King, L. and Fabian, A. C. and McNamara, B. and Hogan, M. and Mezcua, M. and Taylor, G. (2018) 'Mystery solved : discovery of extended radio emission in the merging galaxy cluster Abell 2146.', Monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society., 475 (2). pp. 2743-2753. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stx3160 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been accepted for publication in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society c : 2017 The Author(s) Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk MNRAS 475, 2743–2753 (2018) doi:10.1093/mnras/stx3160 Advance Access publication 2017 December 8 Mystery solved: discovery of extended radio emission in the merging galaxy cluster Abell 2146 J. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93, -

X-Ray Study of the Merging Galaxy Cluster Abell 3411-3412 with XMM-Newton and Suzaku X

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. abell3411 c ESO 2020 August 3, 2020 X-ray study of the merging galaxy cluster Abell 3411-3412 with XMM-Newton and Suzaku X. Zhang1; 2, A. Simionescu2; 1; 3, H. Akamatsu2, J. S. Kaastra2; 1, J. de Plaa2, and R. J. van Weeren1 1 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Sorbonnelaan 2, 3584 CA Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (WPI), The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8583, Japan August 3, 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Chandra observations of the Abell 3411-3412 merging galaxy cluster system have previously revealed an outbound bullet- like sub-cluster in the northern part and many surface brightness edges at the southern periphery, where multiple diffuse sources are also reported from radio observations. Notably, a south-eastern radio relic associated with fossil plasma from a radio galaxy and with a detected X-ray edge provides direct evidence of shock re-acceleration. The properties of the reported surface brightness features have yet to be constrained from a thermodynamic view. Aims. We use the XMM-Newton and Suzaku observations of Abell 3411-3412 to reveal the thermodynamical nature of the previously reported re-acceleration site and other X-ray surface brightness edges. Meanwhile, we aim to investigate the temperature profile in the low-density outskirts with Suzaku data. Methods. We perform both imaging and spectral analysis to measure the density jump and the temperature jump across multiple known X-ray surface brightness discontinuities. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 29 March 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hlavacek-Larrondo, J. and Gendron-Marsolais, M.-L. and Fecteau-Beaucage, D. and van Weeren, R. J. and Russell, H. R. and Edge, A. and Olamaie, M. and Rumsey, C. and King, L. and Fabian, A. C. and McNamara, B. and Hogan, M. and Mezcua, M. and Taylor, G. (2018) 'Mystery solved : discovery of extended radio emission in the merging galaxy cluster Abell 2146.', Monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society., 475 (2). pp. 2743-2753. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stx3160 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been accepted for publication in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society c : 2017 The Author(s) Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Mon. -

De 1999 À 2020 L'astronomie Volume 114 - Année 1999 Index Par Auteurs

INDEX de 1999 à 2020 L'Astronomie volume 114 - Année 1999 index par auteurs AUTEURS TITRE N° Page Agati JL, Mauroy P Commission des étoiles doubles : réunion du 7/3/1998 1 26 Alhalel T Le mouvement lunaire 6 172 Arioli H Observation de l'éclipse à Amasya (Turquie) 12 360 Artzner G Le soleil en relief 12 377 Bacchus P Visite à la REOSC 1 28 Baudin F, Koutchmy S L'éclipse du 11 août 1999 et la couronne 12 326 Commission des étoiles doubles, Strasbourg 29 et 30 Bonneau D, Morlet G, Salaman M 6 194 08/1998 Borra EF Télescopes à miroir liquide 7 212 Boust D L'éclipse totale au Cap de la Hague 12 362 Chapelet M L'essaim des Léonides en Novembre 1999 10 270 Chappelet J Un cadran solaire scolaire 10 260 Coué P Les sondes japonaises dans le système solaire 3 46 Coué P Retour sur la Lune 7 220 Coué P Le 50 ème Congrès de l'IAF 11 293 Courdurié C, Thiot A Commission du Soleil : réunion du 21 novembre 1998 5 152 Davoust E L'oeuvre de Jean Rösch au Pic-du-Midi 11 312 Dawidowicz G Cartographie de Mars : La phase complète a commencé 3 42 Dawidowicz G Eclipses de Soleil sur Mars 11 278 Debackere, Martel, Lancelot Ils ont vécu l'éclipse ...Ils la racontent 2 12 345 Débarbat S Cassini et ses découvertes dans le système de Saturne 10 248 Débarbat S Eclipses totales de Soleil en Europe depuis le XV ème s 5 128 Delahaye F Expérience radioastronomique 12 356 Dollfus A Observation de Mars avec la Grande Lunette de Meudon 7 230 Dumont R La France, les femmes et l'astronomie 1 22 Dumont S, Dumont R Anniversaires astronomiques 1 2 ESA Mission Cassini-Huygens ..dernières -

Isolated Elliptical Galaxies

Isolated Elliptical Galaxies Fatma Mohamed Reda Mahmoud Mohamed (M.Sc.) A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Information and Communication Technology Swinburne University of Technology 2007 Abstract This thesis presents a detailed study of a well defined sample of isolated early-type galaxies. We define a sample of 36 nearby isolated early-type galaxies using a strict isolation criteria. New wide-field optical imaging of 20 isolated galaxies confirms their early-type morphology and relative isolation. We find that the isolated galaxies reveal a colour-magnitude relation similar to cluster ellipticals, which suggests that they formed at a similar epoch to cluster galaxies, such that the bulk of their stars are very old. However, several galaxies of our sample reveal evidence for dust lanes, plumes, shells, boxy and disk isophotes. Thus at least some isolated galaxies have experienced a recent merger/accretion event which may have also induced a small burst of star formation. Using new long-slit spectra of 12 galaxies we found that, isolated galaxies follow similar scaling relations between central stellar population parameters, such as age, metallicity [Z/H] and α-element abundance [E/Fe], with galaxy velocity dispersion to their counterparts in high density environments. However, isolated galaxies tend to have slightly younger ages, higher metallicities and lower abundance ratios. Such properties imply an extended star formation history for galaxies in lower density environments. We measure age gradients that anticorrelate with the central galaxy age. Thus as a young starburst evolves, the age gradient flattens from positive to almost zero. -

Diffuse Radio Emission from Galaxy Clusters

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Diffuse Radio Emission from Galaxy Clusters R. J. van Weeren · F. de Gasperin · H. Akamatsu · M. Br¨uggen · L. Feretti · H. Kang · A. Stroe · F. Zandanel Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract In a growing number of galaxy clusters dif- ICM. Cluster radio shocks (relics) are polarized sources fuse extended radio sources have been found. These mostly found in the cluster's periphery. They trace sources are not directly associated with individual clus- merger induced shock waves. Revived fossil plasma ter galaxies. The radio emission reveal the presence sources are characterized by their radio steep-spectra of cosmic rays and magnetic fields in the intracluster and often irregular morphologies. In this review we medium (ICM). We classify diffuse cluster radio sources give an overview of the properties of diffuse cluster ra- into radio halos, cluster radio shocks (relics), and re- dio sources, with an emphasis on recent observational vived AGN fossil plasma sources. Radio halo sources results. We discuss the resulting implications for the can be further divided into giant halos, mini-halos, underlying physical acceleration processes that oper- and possible \intermediate" sources. Halos are gener- ate in the ICM, the role of relativistic fossil plasma, ally positioned at cluster center and their brightness and the properties of ICM shocks and magnetic fields. approximately follows the distribution of the thermal We also compile an updated list of diffuse cluster ra- dio sources which will be available on-line (http:// galaxyclusters.com). We end this review with a dis- R. J. van Weeren cussion on the detection of diffuse radio emission from Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 the cosmic web. -

Exploring the Optical Transient Sky with the Palomar Transient Factory

Draft version June 30, 2009 A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 6/22/04 EXPLORING THE OPTICAL TRANSIENT SKY WITH THE PALOMAR TRANSIENT FACTORY Arne Rau1,2, Shrinivas R. Kulkarni1, Nicholas M. Law1, Joshua S. Bloom3, David Ciardi4, George S. Djorgovski1, Derek B. Fox5, Avishay Gal-Yam6, Carl C. Grillmair7, Mansi M. Kasliwal1, Peter E. Nugent8, Eran O. Ofek1, Robert M. Quimby1, William T. Reach9, Michael Shara10, Lars Bildsten11, S. Bradley Cenko3, Andrew J. Drake1, Alexei V. Filippenko3, David J. Helfand12, George Helou9, D. Andrew Howell13,14, Dovi Poznanski3,8, Mark Sullivan15 1 Caltech Optical Observatories, MS 105-24, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2 Max-Planck Institute for extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, 85748, Germany 3 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411, USA 4 Michelson Science Center, MS 100-22, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA 6 Benoziyo Center for Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, 76100 Rehovot, Israel 7 Spitzer Science Center, MS 220-6, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 8 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 9 Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, California Institute of Technology, MS 100-22, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 10 Department of Astrophysics, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA 11 Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics and Department of Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA 12 Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA 13 Las Cumbres Global Telescope Network, 6740 Cortona Dr. -

Diffuse Radio Emission from Galaxy Clusters

Space Sci Rev (2019) 215:16 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-019-0584-z Diffuse Radio Emission from Galaxy Clusters R.J. van Weeren1 · F. de Gasperin2 · H. Akamatsu3 · M. Brüggen2 · L. Feretti4 · H. Kang5 · A. Stroe6,7 · F. Zandanel 8 Received: 26 October 2018 / Accepted: 18 January 2019 / Published online: 5 February 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract In a growing number of galaxy clusters diffuse extended radio sources have been found. These sources are not directly associated with individual cluster galaxies. The ra- dio emission reveal the presence of cosmic rays and magnetic fields in the intracluster medium (ICM). We classify diffuse cluster radio sources into radio halos, cluster radio shocks (relics), and revived AGN fossil plasma sources. Radio halo sources can be further divided into giant halos, mini-halos, and possible “intermediate” sources. Halos are gener- ally positioned at cluster center and their brightness approximately follows the distribution of the thermal ICM. Cluster radio shocks (relics) are polarized sources mostly found in the cluster’s periphery. They trace merger induced shock waves. Revived fossil plasma sources are characterized by their radio steep-spectra and often irregular morphologies. In this re- view we give an overview of the properties of diffuse cluster radio sources, with an empha- sis on recent observational results. We discuss the resulting implications for the underlying physical acceleration processes that operate in the ICM, the role of relativistic fossil plasma, and the properties of ICM shocks and magnetic fields. We also compile an updated list of diffuse cluster radio sources which will be available on-line (http://galaxyclusters.com). -

Isolated Elliptical Galaxies

Isolated Elliptical Galaxies Fatma Mohamed Reda Mahmoud Mohamed (M.Sc.) A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Information and Communication Technology Swinburne University of Technology 2007 Abstract This thesis presents a detailed study of a well defined sample of isolated early-type galaxies. We define a sample of 36 nearby isolated early-type galaxies using a strict isolation criteria. New wide-field optical imaging of 20 isolated galaxies confirms their early-type morphology and relative isolation. We find that the isolated galaxies reveal a colour-magnitude relation similar to cluster ellipticals, which suggests that they formed at a similar epoch to cluster galaxies, such that the bulk of their stars are very old. However, several galaxies of our sample reveal evidence for dust lanes, plumes, shells, boxy and disk isophotes. Thus at least some isolated galaxies have experienced a recent merger/accretion event which may have also induced a small burst of star formation. Using new long-slit spectra of 12 galaxies we found that, isolated galaxies follow similar scaling relations between central stellar population parameters, such as age, metallicity [Z/H] and α-element abundance [E/Fe], with galaxy velocity dispersion to their counterparts in high density environments. However, isolated galaxies tend to have slightly younger ages, higher metallicities and lower abundance ratios. Such properties imply an extended star formation history for galaxies in lower density environments. We measure age gradients that anticorrelate with the central galaxy age. Thus as a young starburst evolves, the age gradient flattens from positive to almost zero. -

High-Resolution VLA Low Radio Frequency Observations of the Perseus Cluster: Radio Lobes, Mini-Halo and Bent-Jet Radio Galaxies

MNRAS 000,1{17 (2020) Preprint 12 November 2020 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 High-resolution VLA low radio frequency observations of the Perseus cluster: radio lobes, mini-halo and bent-jet radio galaxies M. Gendron-Marsolais1?, J. Hlavacek-Larrondo2, R. J. van Weeren3, L. Rudnick4, T. E. Clarke5, B. Sebastian6, T. Mroczkowski7, A. C. Fabian8, K. M. Blundell9, E. Sheldahl10, K. Nyland11, J. S. Sanders12, W. M. Peters5, and H. T. Intema3 1European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Co´ordova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Santiago de Chile 2D´epartement de Physique, Universit´ede Montr´eal, Montr´eal, QC H3C 3J7, Canada 3Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, NL-2333CA, Leiden, The Netherlands 4Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Minnesota, 116 Church Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 5Naval Research Laboratory, Code 7213, 4555 Overlook Ave. SW, Washington, DC 20375, USA 6National Center for Radio Astrophysics - Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Post Box 3, Ganeshkhind P.O., Pune 41007, India 7European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, DE-85748 Garching b. Munchen,¨ Germany 8Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA 9University of Oxford, Astrophysics, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH, UK 10University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA 11 National Research Council, resident at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, 4555 Overlook Ave. SW, Washington, DC 20375, USA 12Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ extraterrestrische Physik, 85748 Garching, Germany Accepted for publication in MNRAS ABSTRACT We present the first high-resolution 230-470 MHz map of the Perseus cluster obtained with the Karl G. -

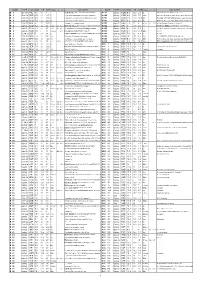

7000 List by Name

NAME TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE Class ns bs SAC NOTES NAME TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE Class ns bs SAC NOTES M 1 SN Rem TAU 8.4 11 8' Crab Nebula; filaments;pulsar 16m;3C144 -M 99 Galaxy COM 9.9 13.2 5.3' Sc SN 1967h;Norton-diff for small scope M 2 Glob CL AQR 6.5 11 11.7' II Lord Rosse-Dark area near core;* mags 13... -M 100 Galaxy COM 9.4 13.4 7.5' SBbc SN 1901-14-59;NGC 4322 @ 5.2';NGC 4328 @ 6.1' M 3 Glob CL CVN 6.3 11 18.6' VI Lord Rosse-sev dark marks within 5' of center -M 101 Galaxy UMA 7.9 14.9 28.5' SBc P w NGC 5474;SN 1909;spir galax w one heavy arm; M 4 Glob CL SCO 5.4 12 26.3' IX Look for central bar structure -M 102 Galaxy DRA 9.9 12.2 6.5' Sa vBN w dk lane and ansae;NGC 5867 small E neb; M 5 Glob CL SER 5.7 11 19.9' V st mags 11...;superb cluster -M 103 Opn CL CAS 7.4 11 6' III 2 p 40 10.6 in Cas OB8;incl Struve 131 6-9m 14'' M 6 Opn CL SCO 4.2 10 20' III 2 p 80 6.2 Butterfly cluster;51 members to 10.5 mag incl var*- BMM104 Sco Galaxy VIR 8 11.6 8.6' Sab Sombrero Galaxy; H I 43;dark equatorial lane; M 7 Opn CL SCO 3.3 12 80' II 2 r 80 5.6 80 members to 10th mag; Ptolemy's cluster -M 105 Galaxy LEO 9.3 12.8 5.3' E1 P w NGC 3384 @ 7.2';NGC 3389 @ 10 ';Leo Group M 8 Opn CL SGR 4.6 - 15' II 2 m n 6.9 In Lagoon nebula M8;25* mags 7..