NAB Reply Comments Re: Video Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Jul 1

The Fifth Estate Broadcasting Jul 1 You'll find more women watching Good Company than all other programs combined: Company 'Monday - Friday 3 -4 PM 60% Women 18 -49 55% Total Women Nielsen, DMA, May, 1985 Subject to limitations of survey KSTP -TV Minneapoliso St. Paul [u nunc m' h5 TP t 5 c e! (612) 646 -5555, or your nearest Petry office Z119£ 1V ll3MXVW SO4ii 9016 ZZI W00b svs-lnv SS/ADN >IMP 49£71 ZI19£ It's hours past dinner and a young child hasn't been seen since he left the playground around noon. Because this nightmare is a very real problem .. When a child is missing, it is the most emotionally exhausting experience a family may ever face. To help parents take action if this tragedy should ever occur, WKJF -AM and WKJF -FM organized a program to provide the most precise child identification possible. These Fetzer radio stations contacted a local video movie dealer and the Cadillac area Jaycees to create video prints of each participating child as the youngster talked and moved. Afterwards, area law enforce- ment agencies were given the video tape for their permanent files. WKJF -AM/FM organized and publicized the program, the Jaycees donated man- power, and the video movie dealer donated the taping services-all absolutely free to the families. The child video print program enjoyed area -wide participation and is scheduled for an update. Providing records that give parents a fighting chance in the search for missing youngsters is all a part of the Fetzer tradition of total community involvement. -

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

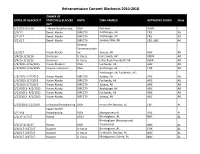

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Appendix a Stations Transitioning on June 12

APPENDIX A STATIONS TRANSITIONING ON JUNE 12 DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LICENSEE 1 ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (D KTXS-TV BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. 2 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC 3 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC 4 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 5 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC 6 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 7 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC 8 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC 9 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 10 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 11 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CW KASY-TV ACME TELEVISION LICENSES OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 12 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM UNIVISION KLUZ-TV ENTRAVISION HOLDINGS, LLC 13 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM PBS KNME-TV REGENTS OF THE UNIV. OF NM & BD.OF EDUC.OF CITY OF ALBUQ.,NM 14 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM ABC KOAT-TV KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. 15 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM NBC KOB-TV KOB-TV, LLC 16 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CBS KRQE LIN OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 17 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM TELEFUTURKTFQ-TV TELEFUTURA ALBUQUERQUE LLC 18 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE CARLSBAD NM ABC KOCT KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. -

Acquisition of Tribune Media Company

Acquisition of Tribune Media Company Enhancing Nexstar’s Position as North America’s Leading Local Media Company December 3, 2018 Disclaimer Forward-Looking Statements This Presentation includes forward-looking statements. We have based these forward-looking statements on our current expectations and projections about future events. Forward-looking statements include information preceded by, followed by, or that includes the words "guidance," "believes," "expects," "anticipates," "could," or similar expressions. For these statements, Nexstar Media and Tribune Media claim the protection of the safe harbor for forward-looking statements contained in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. The forward-looking statements contained in this presentation, concerning, among other things, the ultimate outcome, benefits and cost savings of any possible transaction between Nexstar Media and Tribune Media and timing thereof, and future financial performance, including changes in net revenue, cash flow and operating expenses, involve risks and uncertainties, and are subject to change based on various important factors, including the timing of and any potential delay in consummating the proposed transaction; the risk that a condition to closing of the proposed transaction may not be satisfied and the transaction may not close; the risk that a regulatory approval that may be required for the proposed transaction is delayed, is not obtained or is obtained subject to conditions that are not anticipated, the risk of the occurrence of any -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

COMPLAINT Plaintiff, Tribune Media Company (“Tribune”), by and Through Its Undersigned Attorneys, Files This Verified Complaint Against Defendant, Sinclair

EFiled: Aug 09 2018 12:05AM EDT Transaction ID 62327554 Case No. 2018-0593- IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE Tribune Media Company, a Delaware corporation, Plaintiff, C.A. No. 2018- _____-_____ v. Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc., a Maryland corporation, Defendant. VERIFIED COMPLAINT Plaintiff, Tribune Media Company (“Tribune”), by and through its undersigned attorneys, files this Verified Complaint against Defendant, Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (“Sinclair”), and alleges as follows: Introduction 1. Tribune and Sinclair are media companies that own and operate local television stations. In May 2017, the companies entered into an Agreement and 1 Plan of Merger (the “Merger Agreement”) pursuant to which Sinclair agreed to acquire Tribune for cash and stock valued at $43.50 per share, for an aggregate purchase price of approximately $3.9 billion (the “Merger”). 1 A true and correct copy of the Merger Agreement is attached as Exhibit A. The Merger Agreement is incorporated herein by reference. Unless defined herein, all capitalized terms in this Verified Complaint have the meanings ascribed to them in the Merger Agreement. RLF1 19833012v.1 2. Sinclair owns the largest number of local television stations of any media company in the United States, and Tribune and Sinclair were well aware that a combination of the two companies would trigger regulatory scrutiny by both the United States Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the Federal Communications Commission (the “FCC”). Because speed and certainty were critical to Tribune, it conditioned its agreement on obtaining from Sinclair a constrictive set of deal terms obligating Sinclair to use its reasonable best efforts to obtain prompt regulatory clearance of the transaction. -

2009-332 TTBG Omaha Opco LLC Previously Pappas Telecasting

2009-332 BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS SARPY COUNTY, NEBRASKA RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING CHAIRMAN TO SIGN ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF RECEIPT OF CHANGE IN NOTICE AND PAYMENT INFORMATION REGARDING EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT TOWER LEASE WHEREAS, pursuant to Neb. Rev. Stat. §23-1 04(6) (Reissue 2007), the County has the power to do all acts in relation to the concerns of the county necessary to the exercise of its corporate powers; and, WHEREAS, pursuant to Neb. Rev. Stat. §23-103 (Reissue 2007), the powers ofthe County as a body are exercised by the County Board; and, WHEREAS, Pappas Telecasting ofthe Midlands has assigned all of its rights, duties and obligations under the agreement to lease tower facilities to Sarpy County dated June 7, 1995 to TTBG Omaha 0pC0, LLC, WHEREAS, TTBG Omaha OpCo, LLC has requested that Sarpy County sign an acknowledgment of change in notice provision and change in address to which lease payments are sent to reflect current ownership by TTBG Omaha 0pC0, LLC, NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SARPY COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS THAT, pursuant to the statutory authority set forth above, the Chairman ofthis Board, together with the County Clerk, be and hereby are authorized to sign on behalf of this Board an acknowledgment ofreceipt ofchange in notice and payment information regarding emergency management tower lease, a copy of which is attached hereto. DATED this 3.,d~daof~ember, 2009. ~ Moved by ~,t:h _~ , seconded by ItJYn q:?i~ ,that the above Resolution be adopte . Carried. NAYS: ABSENT: <-/j(ltlJ ABSTAIN: <tl@l Approved as to~ ~Deputy County Attorney TTBG OMAHA OPCO, LLC 4625 Farnam Street Omaha, NE 68132-3222 October 15, 2009 VIA CERTIFIED MAIL - RETURN RECEIPT Emergency Management and Communication Agency Sarpy County Sheriff Sarpy County Courthouse Attn: Larry Lavelle 121 0 Golden Gate Drive Papillion, NE 68046 Re: Notice of Assignment and Assumption of Lease (the "Notice") Lease Agreement, dated 6/7/95, as extended (the "Lease") Dear Mr. -

Sly Fox Buys Big, Gets Back On

17apSRtop25.qxd 4/19/01 5:19 PM Page 59 COVERSTORY Sly Fox buys big, The Top 25 gets back on top Television Groups But biggest station-group would-be Spanish-language network, Azteca America. Rank Network (rank last year) gainers reflect the rapid Meanwhile, Entravision rival Telemundo growth of Spanish-speaking has made just one deal in the past year, cre- audiences across the U.S. ating a duopoly in Los Angeles. But the 1 Fox (2) company moved up several notches on the 2 Viacom (1) By Elizabeth A. Rathbun Top 25 list as Univision swallowed USA. ending the lifting of the FCC’s owner- In the biggest deal of the past year, News 3 Paxson (3) ship cap, the major changes on Corp./Fox Television made plans to take 4 Tribune (4) PBROADCASTING & CABLE’s compila- over Chris-Craft Industries/United Tele- tion of the nation’s Top 25 TV Groups reflect vision, No. 7 on last year’s list. That deal 5 NBC (5) the rapid growth of the Spanish-speaking finally seems to be headed for federal population in the U.S. approval. 6 ABC (6) The list also reflects Industry consolidation But the divestiture 7 Univision (13) the power of the Top 25 doesn’t alter that News Percent of commercial TV stations 8 Gannett (8) groups as whole: They controlled by the top 25 TV groups Corp. returns to the control 44.5% of com- top after buying Chris- 9 Hearst-Argyle (9) mercial TV stations in Craft. This year, News the U.S., up about 7% Corp. -

WASHINGTON FREEDOM 2009 MEDIA GUIDE 2009 SCHEDULE DATE GAME TIME TV Sun., March 29 at Los Angeles Sol 6 P.M

WASHINGTON FREEDOM 2009 MEDIA GUIDE 2009 SCHEDULE DATE GAME TIME TV Sun., March 29 at Los Angeles Sol 6 p.m. FSC Sat., April 11 Chicago Red Stars 6 p.m. FSC Sat., April 18 Boston Breakers 7 p.m. Sun., April 26 at FC Gold Pride 6 p.m. FSC Sun., May 3 Saint Louis Athletica 6 p.m. FSC Sun., May 17 at Boston Breakers 6 p.m. FSC Sun., May 23 Sky Blue FC (at RFK) 5 p.m. Sun., May 31 FC Gold Pride 4 p.m. Sun., June 7 at Los Angeles Sol 6 p.m. FSC Sat., June 13 Chicago Red Stars (at RFK) 5 p.m. Sat., June 20 at Saint Louis Athletica 8 p.m. Wed., June 24 at Boston Breakers 7 p.m. Wed., July 1 at Chicago Red Stars 8:30 p.m. Sun., July 5 Los Angeles Sol 6 p.m. FSC Wed., July 15 at Sky Blue FC 7 p.m. Sat., July 18 Saint Louis Athletica (at RFK) 5:30 p.m. Sun., July 26 at Chicago Red Stars 7 p.m. Wed., July 29 Boston Breakers 8 p.m. Sat., Aug. 1 at FC Gold Pride 6 p.m. Sat., Aug. 8 Sky Blue FC 7 p.m. Sat., Aug. 15 First Round, WPS Playoffs TBD Wed., Aug. 18 Super Semifinal, WPS Playoffs TBD Sat., Aug. 22 WPS Final TBD 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Team Directory 3 Freedom History 4 Maureen Hendricks, Chairwoman, Freedom Soccer LLC 8 Jim Gabarra, Head Coach 9 Clyde Watson, Assistant Coach 10 Nicci Wright, Goalkeeper Coach 11 About the Maryland SoccerPlex 12 Directions to the Maryland SoccerPlex 14 Tickets/Seating information 15 Player rosters and bios 16 bompastor, dedycker, de vanna, eyorokon, gilbeau, huffman, janss, karniski, keller, lindsey, lohman, long, mcleod, moros, sauerbrunn, sawa, scurry, singer, spisak, wambach, whitehill, zimmeck, glory Opponents -

Children's Television Programming

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Children’s Television Programming ) MB Docket No. 18-202 Rules ) ) Modernization of Media Regulation ) MB Docket No. 17-105 Initiative ) REPLY COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCASTERS Rick Kaplan Jerianne Timmerman Emmy Parsons October 23, 2018 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 II. CLAIMS THAT THE FCC LACKS AUTHORITY TO AMEND ITS CHILDREN’S TV RULES ARE SPECIOUS…………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………….4 A. The General Public Interest Standard Does Not Require the Retention of the Existing Children’s TV Rules. ...................................................................................................................... 5 B. The FCC Has the Discretion Under the CTA’s General Terms to Update its Children’s TV Rules and the Obligation to Do So Under the Administrative Procedure Act. ..................................... 8 III. THE FCC MUST REJECT FACTUALLY INACCURATE AND LEGALLY INCORRECT CLAIMS THAT THE EXISTING CHILDREN’S TV REGULATORY REGIME SHOULD REMAIN INTACT BECAUSE BROADCASTERS HAVE “FREE” LICENSES ....................................................................................... 11 IV. THE RECORD SHOWS THAT CHILDREN’S VIEWING HABITS HAVE CHANGED DRAMATICALLY AND THAT FEWER AND FEWER YOUNG VIEWERS RELY ON LINEAR BROADCAST TV FOR E/I CONTENT ............................................................................................................................. -

News Release

News Release Contact: David Amy, EVP & CFO, Sinclair Lucy Rutishauser, VP & Treasurer, Sinclair (410) 568-1500 SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP ANNOUNCES AGREEMENT TO PURCHASE FREEDOM COMMUNICATIONS TELEVISION STATIONS BALTIMORE (November 2, 2011) -- Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI), the “Company” or “Sinclair,” announced today that it has entered into a definitive agreement to purchase the broadcast assets of Freedom Communications (“Freedom”) for $385.0 million. Freedom owns and operates eight stations in seven markets, reaching 2.63% of the U.S. TV households. The transaction is subject to Freedom’s shareholder approval which must be obtained by November 8, 2011, approval by the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”), and customary antitrust clearance. Following receipt of antitrust approval of the transaction, which is expected to occur within thirty days, and prior to closing of the acquisition, Sinclair will operate the stations pursuant to a Local Marketing Agreement. The companies anticipate closing and funding of the acquisition to occur late in the first quarter/early in the second quarter of 2012. Upon closing, the Company expects to finance the $385.0 million purchase price, less a $38.5 million deposit payable upon Freedom’s shareholder approval, either through a bank loan or by accessing the capital markets. “We are excited about bringing the Freedom stations into the Sinclair portfolio, particularly in light of our recent agreement to acquire seven television stations from Four Points Media,” commented David Smith, President and CEO of Sinclair. “Not only will this transaction, when coupled with the Four Points transaction, result in us owning two full power stations in compliance with FCC regulations in West Palm Beach, Freedom’s largest market, but it allows us to expand our middle market position and network diversification.