Examining Foreign Direct Investment in Mon State, Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa- an Townships, September to November 2014

Situation Update February 10, 2015 / KHRG #14-101-S1 Thaton Situation Update: Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa- an townships, September to November 2014 This Situation Update describes events occurring in Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa-an townships, Thaton District during the period between September to November 2014, including armed groups’ activities, forced labour, restrictions on the freedom of movement, development activities and access to education. th • On October 7 2014, Border Guard Force (BGF) Battalion #1014 Company Commander Tin Win from Htee Soo Kaw Village ordered A---, B---, C--- and D--- villagers to work for one day. Ten villagers had to cut wood, bamboo and weave baskets to repair the BGF army camp in C--- village, Hpa-an Township. • In Hpa-an Township, two highways were constructed at the beginning of 2013 and one highway was constructed in 2014. Due to the construction of the road, villagers who lived nearby had their land confiscated and their plants and crops were destroyed. They received no compensation, despite reporting the problem to Hpa-an Township authorities. • In the academic year of 2013-2014 more Burmese government teachers were sent to teach in Karen villages. Villagers are concerned as they are not allowed to teach the Karen language in the schools. Situation Update | Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa-an townships, Thaton District (September to November 2014) The following Situation Update was received by KHRG in December 2014. It was written by a community member in Thaton District who has been trained by KHRG to monitor local human rights conditions. It is presented below translated exactly as originally written, save for minor edits for clarity and security.1 This report was received along with other information from Thaton District, including one incident report.2 This report concerns the situation in the region, the villagers’ feelings, armed groups’ activities, forced labour, development activities, support to villagers and education problems occurring between the beginning of September and November 2014. -

Gulf of Mottama Management Plan

GULF OF MOTTAMA MANAGEMENT PLAN PROJECT IMPLEMTATION AND COORDINATION UNIT – PCIU COVER DESIGN: 29, MYO SHAUNG RD, TAUNG SHAN SU WARD, MAWLAMYINE, NYANSEIK RARMARN MON STATE, MYANMAR KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION OFFICER GULF OF MOTTAMA PROJECT (GOMP) Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 GULF OF MOTTAMA MANAGEMENT PLAN Published: 16 May 2019 This management plan is endorsed by Mon State and Bago Regional Governments, to be adopted as a guidance document for natural resource management and sustainable development for resilient communities in the Gulf of Mottama. 1 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 This page is intentionally left blank 2 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 Gulf of Mottama Project (GoMP) GoMP is a project of Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and is implemented by HELVETAS Myanmar, Network Activities Group (NAG), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association(BANCA). 3 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The drafting of this Gulf of Mottama Management Plan started early 2016 with an integrated meeting on May 31 to draft the first concept. After this initial workshop, a series of consultations were organized attended by different people from several sectors. Many individuals and groups actively participated in the development of this management plan. We would like to acknowledge the support of the Ministries and Departments who have been actively involved at the Union level which more specifically were Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Forest Department, Department of Agriculture, Department of Fisheries, Department of Rural Development and Environmental Conservation Department. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006

Burma Page 1 of 24 2005 Human Rights Report Released | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Since 1962, Burma, with an estimated population of more than 52 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The current controlling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, is the country's de facto government, with subordinate Peace and Development Councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a generally free and fair parliamentary election, but the junta refused to recognize the results. Twice during the year, the SPDC convened the National Convention (NC) as part of its purported "Seven-Step Road Map to Democracy." The NC, designed to produce a new constitution, excluded the largest opposition parties and did not allow free debate. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year, and the government continued to commit numerous serious abuses. The following human rights abuses were reported: abridgement of the right to change the government extrajudicial killings, including custodial deaths disappearances rape, torture, and beatings of -

Forced Migration and Land Rights in Burma

-R&YVQE,SYWMRK0ERHERH4VSTIVX] ,04 VMKLXWEVIMRI\XVMGEFP]PMROIHXSXLIGSYRXV]«W SRKSMRKWXVYKKPIJSVNYWXMGIERHHIQSGVEG]ERHWYWXEMREFPIPMZIPMLSSHW7MRGI[LIRXLI QMPMXEV]VIKMQIXSSOTS[IVSZIVSRIQMPPMSRTISTPILEZIFIIRHMWTPEGIHEWYFWXERXMZIRYQFIV EVIJVSQIXLRMGREXMSREPMX]GSQQYRMXMIWHIRMIHXLIVMKLXXSVIWMHIMRXLIMVLSQIPERHW0ERH GSR´WGEXMSRF]+SZIVRQIRXJSVGIWMWVIWTSRWMFPIJSVQER]WYGL,04ZMSPEXMSRWMR&YVQE -R'3,6)GSQQMWWMSRIH%WLPI]7SYXLSRISJXLI[SVPH«WPIEHMRK&YVQEVIWIEVGLIVWXS GEVV]SYXSRWMXIVIWIEVGLSR,04VMKLXW8LIIRWYMRKVITSVX(MWTPEGIQIRXERH(MWTSWWIWWMSR *SVGIH1MKVEXMSRERH0ERH6MKLXWMR&YVQEJSVQWEGSQTVILIRWMZIPSSOEXXLIOI],04 MWWYIWEJJIGXMRK&YVQEXSHE]ERHLS[XLIWIQMKLXFIWXFIEHHVIWWIHMRXLIJYXYVI Displacement and Dispossession: 8LMWVITSVX´RHWXLEXWYGLTVSFPIQWGERSRP]FIVIWSPZIHXLVSYKLWYFWXERXMEPERHWYWXEMRIH GLERKIMR&YVQEETSPMXMGEPXVERWMXMSRXLEXWLSYPHMRGPYHIMQTVSZIHEGGIWWXSEVERKISJ Forced Migration and Land Rights JYRHEQIRXEPVMKLXWEWIRWLVMRIHMRMRXIVREXMSREPPE[ERHGSRZIRXMSRWMRGPYHMRKVIWTIGXJSV ,04VMKLXW4VSXIGXMSRJVSQ ERHHYVMRK JSVGIHQMKVEXMSRERHWSPYXMSRWXSXLI[MHIWTVIEH ,04GVMWIWMR&YVQEHITIRHYPXMQEXIP]SRWIXXPIQIRXWXSXLIGSRµMGXW[LMGLLEZI[VEGOIHXLI GSYRXV]JSVQSVIXLERLEPJEGIRXYV] BURMA )JJSVXWEXGSRµMGXVIWSPYXMSRLEZIXLYWJEVQIX[MXLSRP]ZIV]PMQMXIHWYGGIWW2IZIVXLIPIWW XLMWVITSVXHIWGVMFIWWSQIMRXIVIWXMRKERHYWIJYPTVSNIGXWXLERLEZIFIIRMQTPIQIRXIHF]GMZMP WSGMIX]KVSYTWMR&YVQE8LIWII\EQTPIWWLS[XLEXRSX[MXLWXERHMRKXLIRIIHJSVJYRHEQIRXEP TSPMXMGEPGLERKIMR&YVQEWXITWGERERHWLSYPHFIXEOIRRS[XSEHHVIWW,04MWWYIW-RTEVXMGYPEV STTSVXYRMXMIWI\MWXXSEWWMWXXLIVILEFMPMXEXMSRSJHMWTPEGIHTISTPIMR[E]W[LMGLPMROTSPMXMGEP -

English 2014

The Border Consortium November 2014 PROTECTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH EAST BURMA / MYANMAR With Field Assessments by: Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) Karen Offi ce of Relief and Development (KORD) Karen Women Organisation (KWO) Karenni Evergreen (KEG) Karenni Social Welfare and Development Centre (KSWDC) Karenni National Women’s Organization (KNWO) Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC) Shan State Development Foundation (SSDF) The Border Consortium (TBC) 12/5 Convent Road, Bangrak, Suite 307, 99-B Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung, Bangkok, Thailand. Yangon, Myanmar. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.theborderconsortium.org Front cover photos: Farmers charged with tresspassing on their own lands at court, Hpruso, September 2014, KSWDC Training to survey customary lands, Dawei, July 2013, KESAN Tatmadaw soldier and bulldozer for road construction, Dawei, October 2013, CIDKP Printed by Wanida Press CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

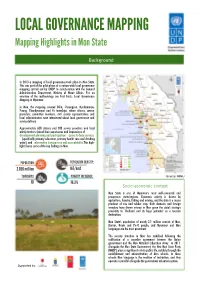

LOCAL GOVERNANCE MAPPING Mapping Highlights in Mon State

LOCAL GOVERNANCE MAPPING Mapping Highlights in Mon State Background In 2013 a mapping of local governance took place in Mon State. This was part of the pilot phase of a nation-wide local governance mapping carried out by UNDP in collaboration with the General Administration Department, Ministry of Home Affairs. For an overview of the methodology see Fast Facts: Local Governance Mapping in Myanmar. In Mon, the mapping covered Bilin, Chaungzon, Kyaikmaraw, Paung, Thanbyuzayat and Ye townships, where citizens, service providers, committee members, civil society representatives and local administrators were interviewed about local governance and service delivery. Approximately 600 citizens and 200 service providers and local administrators shared their experiences and impressions of d e v e l o p m e n t p l a n n i n g a n d p a r t i c i p a t i o n a, c c e s s t o b a s i c s e r v i c e s (specifically primary education, primary health care and drinking water), and i n f o r m a t i o n t r a n s p a r e n c y a n d a c c o u n t a b i l i t y .This high- light shares some of the key findings in Mon. POPULATION: POPULATION DENSITY: 2.050 million 167/km2 TOWNSHIPS: POVERTY INCIDENCE: Source: MIMU 10 16.3% Socio-economic context Mon State is one of Myanmar's most well-connected and prosperous states/regions. -

Excursion Group Visits Model Paddy and Sunflower Farms in Wundwin

Established 1914 Volume XIX, Number 144 Fullmoon Day of Tawthalin 1373 ME Monday, 12 September, 2011 Excursion group visits model True patriotism * It is very important for every one paddy and sunflower farms of the nation regardless of the place he lives to have strong in Wundwin Township Union Spirit. * Only Union Spirit is the true NAY PYI TAW, 11 Sept—Union Minister for seeds are to be distributed to farmers and it is patriotism all the nationalities will Agriculture and Irrigation U Myint Hlaing, Deputy necessary to establish model paddy farms in com- Minister U Ohn Than, the secretary of Pyithu Hluttaw ing summer for production of 200 baskets of paddy have to safeguard. Agriculture and Livestock Breeding Development per acre.—MNA Committee and party this morning arrived at the farm of Agricultural Research Department near Sibin Village of Yamethin Township. The director-general of Agricultural Re- search Department reported on production of hybrid sunflower and F-1 hybrid sunflower that can pro- duce 220 viss of edible oil per acre. The Union Minister gave instructions on extended cultivation of hybrid sunflower and es- tablishment of F-1 hybrid sunflower model farms by Agricultural Research Department and Myanma Agriculture Service for production of sunflower seeds in attracting the private sector. At Chaungmagyi 50-acre sunflower farm of MAS in Pyawbwe Township, the Union Minister gave instructions. After viewing 30-acre hybrid paddy seed production farm and 10-acre hybrid sunflower farm in Shwedaung Farm of Wundwin Township, the Union Minister stressed the need for experts to Union Minister for Agriculture and Irrigation U Myint Hlaing meets local farmers at 50-acre concentrate the production of F-1 hybrid paddy seeds to exceed the target. -

SIRP Fourpager

Midwife Aye Aye Nwe greets one of her young patients at the newly constructed Rural Health Centre in Kyay Thar Inn village (Tanintharyi Region). PHOTO: S. MARR, BANYANEER More engaged, better connected In brief: results of the Southeast Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (SIRP), Myanmar I first came to this village”, says Aye Aye Nwe, Following Myanmar’s reform process and ceasefires with local “When “things were so different.” Then 34 years old, the armed groups, the opportunity arose to finally improve conditions midwife first came to Kyay Thar Inn village in 2014. - advancing health, education, infrastructure, basic services. “It was my first post. When I arrived, there was no clinic. The The task was huge, and remains considerable today despite village administrators had built a house for me - but it was not a the progress that has been achieved over recent years. clinic! Back then, villagers had no full coverage of vaccinations and healthcare - neither for prevention nor treatment.” The project The Southeast Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (SIRP) was The nearest rural health centre was eleven kilometres away - a designed to support this process. Starting in late 2012, a long walk over roads that are muddy in the wet season and dusty consortium of Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), the Swiss in the dry. Unsurprisingly, says Nwe, “the health knowledge of Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the Karen villagers was quite poor. They did not know that immunisations Development Network (KDN)* and Action Aid Myanmar (AAM) are a must. Women did not get antenatal care or assistance of sought to enhance lives and living conditions in 89 remote midwives during delivery.” villages across Myanmar’s southeast. -

HURFOM Report Shows Worrying Trend in Sexual Violence Against Children

issue No. 3/2018 | SEPTEMBER 2018 News, Report, Analysis and Activities on Human Rights Situation in Mon Territory issue No. 3/2018 | SEPTEMBER 2018 The Publication of the Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) “We Still Want Our Land Back”: HURFOM interview with victims of land confiscation “The plot we bought for our house was about 40x60 ft. It was located between Wae Rat and Wae Gali villages [of Thanbyuzayat Township]. We bought it in 2004. Six months after we bought it, Artillery Battalion No. 315 confiscated it. “We bought the plot for 1.35 million kyat in 2004 [equivalent to 30 to 40 million kyats or US $21,084 to $28,112 odat y]. When we bought the plot we had no immediate plans to stay on it. We worked in Thailand and left the plot in its original state. Other people were doing the same as us. After we bought the plot, we had no money to build a house. So we went to Thailand to work and save money to build a house. But even though we had been planning to build a house on the land, the military confiscated it and fenced it July 17, 2018 off with barbed wire. HURFOM: On July 1st 2018, HURFOM met with two victims of land confiscation, “After the military confiscated our plot Nai Lin Aung and Mi Aye Mi San, a couple from Wae Rat village, Thanbyuzayat of land, we didn’t ask anything about Township, Mon State. Their land was confiscated by Burma Army Artillery Battalion No. 315 in 2004. -

International Community Driven Development Specialist - Myanmar

Vacancy Announcement VNG International is seeking a qualified and committed person for the position of: International Community Driven Development Specialist - Myanmar Location: Myanmar (Chaungzon, Bilin and Paung Townships in Mon State and Tanintharyi Township in Tanintharyi Region) Contract duration: 7 months intermittent input in 2017 (extension up to 2 years part-time foreseen subject to satisfactory performance). About VNG International: VNG International is the International Cooperation Agency of the Association of Netherlands Municipalities (VNG), which provides expertise in the area of decentralization and local governance (see www.vng-international.nl). Background and aim of the project: In Myanmar, VNG International currently implements the project Township Level Technical Assistance in four townships in Mon State and Tanintharyi Region, as part of the National Community Driven Development Project (NCDDP). The objective of NCDDP is to enable poor rural communities to benefit from improved access to and use of basic infrastructure and services through a people-centered approach (http://cdd.drdmyanmar.org/). The NCDDP is implemented in 47 townships in Myanmar and managed by the Department of Rural Development of the Myanmar Ministry Of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, with support of the World Bank. Aim of this consultancy is to coordinate and guide the effective implementation of the National Community Driven Development Project in Tanintharyi Township, Bilin Township, Chaungzon Township and Paung Township on behalf of VNG International. Roles and responsibilities of the Community Driven Development Specialist Promote actively and on a continuous basis a sound and professional working relationship between the Department of Rural Development (DRD), Township Technical Assistance (TTA) and all other stakeholders in the assigned township cluster. -

Social Impact and Prevention of Flood and Landslide in Mon State, Myanmar

Social Impact and Prevention of ICT Virtual Organization of ASEAN Flood and Landslide in Mon State, Institutes and NICT Myanmar ASEAN IVO Forum 2019 Nov.20, 2019 Manila, The Philippines Thet Thet Zin University of Computer Studies, Thaton, Myanmar [email protected] 1 • Kyaikmaraw and Ye townships in Mawlamyine are the worse in flooding among the most severely hit. • According to news and residents, 90 percent of Ye was under water, and the total of 375 houses destroyed. Food, clothes and other emergency relief goods are much needed. • Thanlwin bridge leading to the town was shut due to flooding on both sides of the bridge. • According to United Nations office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Myanmar in 2019 people displaced due to monsoon flood was 37,240 people in Mon State. • Some of the houses are destroyed and some are damaged. Schools in flooding area are closed during flooding time and children loosed Abstract their text books, note books and other schooling material during Natural disasters are complex injurious events flooding. that occur entirely beyond the control of • Famers and fisher men faced economic problems and difficult for humans. During present year, flooding and food during this time. landslide are major challenge in Mon State in • Government and civil society organizations supported water, rice, Myanmar. In Landslide area, the official death medicine and other emergency things in these townships. toll has steadily risen over a week and stands • According to 2014 census data, in Mon State, 72 persons live in at 75, according to the township rural areas while 28 persons live in urban areas. -

Myanmar’S Obligations Under International Law

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 Recent Developments ................................................................................................ 2 Background ................................................................................................................ 3 Burmese migrant workers in Thailand ....................................................................... 4 Economic developments ............................................................................................ 5 Myanmar’s obligations under international law ........................................................ 7 Economic and social inequality in Myanmar ............................................................. 7 II. FORCED LABOUR .................................................................................................. 9 Introduction and background ..................................................................................... 9 Forced portering ....................................................................................................... 11 Forced labour involving women and children ......................................................... 12 Forced labour on infrastructure projects .................................................................. 13 The impact of forced labour on the civilian population