In-Depth Analysis of Child Labour and Education in Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

Mapa De Valores De Terrenos Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 6 Puntarenas Cantón 02 Esparza

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 6 PUNTARENAS CANTÓN 02 ESPARZA 421000 424500 428000 431500 435000 438500 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos Estero de Mata de Limón por Zonas Homogéneas ESCALA 1:15.000 422000 423500 Provincia 6 Puntarenas Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Peñas Blancas Cantón 02 Esparza Área de Protección Río Jabonal ón Fila Carballo Plaza am R Quebrada Moncha Salón Comunal an 1119000 S 1119000 Peñas Blancas A nm 6 02 06 R22/U22 Iglesia æCatólica 6 02 06 R20/U20 Targuasal 6 02 05 R05/U05 La Moncha Qu 6 02 06 U04/U05 eb 6 02 06 R06/U06 rad Figueroa a Lim on al 1098500 Ministerio de Hacienda Órgano de Normalización Técnica Marisquería Mar Azul Playa Caldera Lomas Castro Escuela Salinas nm 6 02 06 U14/U15 Cuesta Molas Galeón Peruano E s te Salinas ro M a ta d e L im ó Ferry Sabana Bonitaæ n CCSS nm 6 02 06 R03 A Miramar a Hotel Luna Perr La CALDERA rada ueb he Q Hotel Costa del Sol balac Cam rada Queb Plaza 1115500 Cerrillos 1115500 nm Escuela Mata de Limón Rest. Tabaris æ Cabinasnm Lela Cementerio San RamónMata de Limón Marisquería La Leda R Bahía de Caldera ío J ab Montes de Oro on Plaza al 6 02 06 U01/U02 CAI 1097000 Océano Pacífico Marisquería Linda Mar 6 02 05 R04/U04 Central de Contenedores Aprobado por: La Loma 6 02 06 R07/U07 Ing. Alberto Poveda Alvarado Cerro Blanco Cerro Piedra de Fuego Agranel Q Director u e b r Órgano de Normalización Técnica a d a G Dirección General de Tributación u a t u SAN JERÓNIMO s o a l Mata de Caña l i 6 02 06 R08/U08 u q n a r Finca Cartago r a B o 6 02 06 U13 í -

Asamblea Legislativa De La República De Costa Rica

ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA DE LA REPÚBLICA DE COSTA RICA (ESTA ACTA AÚN NO HA SIDO APROBADA POR EL PLENARIO LEGISLATIVO) ACTA DE LA SESIÓN PLENARIA N.º 6 (Martes 8 de mayo de 2012) TERCERA LEGISLATURA (Del 1º de mayo 2012 al 30 de abril 2013) PRIMER PERÍODO DE SESIONES ORDINARIAS (Del 1º de mayo al 31 de julio de 2012) DEPARTAMENTO DE SERVICIOS PARLAMENTARIOS ÁREA DE ACTAS, SONIDO Y GRABACIÓN ACTA N.º 6 DE 8-5-2012 2 ACTA DE LA SESIÓN PLENARIA N.º 6 MARTES 8 DE MAYO DE 2012 PRIMER PERÍODO DE SESIONES ORDINARIAS TERCERA LEGISLATURA DIRECTORIO Víctor Emilio Granados Calvo PRESIDENTE Rita Gabriela Chaves Casanova Xinia María Espinoza Espinoza PRIMERA SECRETARIA SEGUNDA SECRETARIA DIPUTADOS PRESENTES Acevedo Hurtado, Juan Bosco Hernández Cerdas, Víctor Acuña Castro, Yolanda Hernández Rivera, Manuel Aiza Campos, Luis Antonio Mendoza García, Juan Carlos Alfaro Murillo, Marielos Mendoza Jiménez, Luis Fernando Angulo Mora, Jorge Alberto Molina Rojas, Fabio Araya Pineda, Edgardo Monge Pereira Claudio Enrique Arias Navarro, Gustavo Muñoz Quesada, Carmen María Avendaño Calvo, Carlos Luis Ocampo Baltodano, Christia María Bejarano Almada, Gloria Oviedo Guzmán, Néstor Manrique Brenes Jiménez, Ileana Pérez Gómez, Alfonso Calderón Castro, Antonio Pérez Hegg, Mirna Patricia Chavarría Ruiz, Ernesto Enrique Pinto Rawson, Rodrigo Chaves Casanova, Rita Gabriela Porras Contreras, José Joaquín Céspedes Salazar, Walter Porras Zúñiga, Pilar Cubero Corrales, Víctor Danilo Quintana Porras, Damaris Delgado Ramírez, Carolina Rodríguez Quesada, José Roberto Enríquez Guevara, -

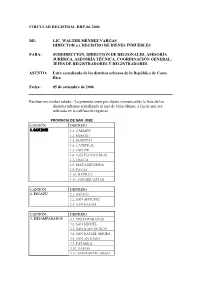

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre Distrito Barrio Nombre Barrio 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 1 Amón 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 2 Aranjuez 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 3 California (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 4 Carmen 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 5 Empalme 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 6 Escalante 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 7 Otoya. 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 1 Bajos de la Unión 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 2 Claret 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 3 Cocacola 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 4 Iglesias Flores 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 5 Mantica 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 6 México 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 7 Paso de la Vaca 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 8 Pitahaya. 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 1 Almendares 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 2 Ángeles 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 3 Bolívar 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 4 Carit 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 5 Colón (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 6 Corazón de Jesús 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 7 Cristo Rey 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 8 Cuba 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 9 Dolorosa (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 10 Merced 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 11 Pacífico (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 12 Pinos 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 13 Salubridad 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 14 San Bosco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 15 San Francisco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 16 Santa Lucía 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 17 Silos. -

Codigos Geograficos

División del Territorio de Costa Rica Por: Provincia, Cantón y Distrito Según: Código 2007 Código Provincia, Cantón y Distrito COSTA RICA 1 PROVINCIA SAN JOSE 101 CANTON SAN JOSE 10101 Carmen 10102 Merced 10103 Hospital 10104 Catedral 10105 Zapote 10106 San Francisco de Dos Ríos 10107 Uruca 10108 Mata Redonda 10109 Pavas 10110 Hatillo 10111 San Sebastián 102 CANTON ESCAZU 10201 Escazú 10202 San Antonio 10203 San Rafael 103 CANTON DESAMPARADOS 10301 Desamparados 10302 San Miguel 10303 San Juan de Dios 10304 San Rafael Arriba 10305 San Antonio 10306 Frailes 10307 Patarrá 10308 San Cristóbal 10309 Rosario 10310 Damas 10311 San Rafael Abajo 10312 Gravilias 10313 Los Guido 104 CANTON PURISCAL 10401 Santiago 10402 Mercedes Sur 10403 Barbacoas 10404 Grifo Alto 10405 San Rafael 10406 Candelaria 10407 Desamparaditos 10408 San Antonio 10409 Chires 105 CANTON TARRAZU 10501 San Marcos 10502 San Lorenzo 10503 San Carlos 106 CANTON ASERRI 10601 Aserrí 10602 Tarbaca o Praga 10603 Vuelta de Jorco 10604 San Gabriel 10605 La Legua 10606 Monterrey 10607 Salitrillos 107 CANTON MORA 10701 Colón 10702 Guayabo 10703 Tabarcia 10704 Piedras Negras 10705 Picagres 108 CANTON GOICOECHEA 10801 Guadalupe 10802 San Francisco 10803 Calle Blancos 10804 Mata de Plátano 10805 Ipís 10806 Rancho Redondo 10807 Purral 109 CANTON SANTA ANA 10901 Santa Ana 10902 Salitral 10903 Pozos o Concepción 10904 Uruca o San Joaquín 10905 Piedades 10906 Brasil 110 CANTON ALAJUELITA 11001 Alajuelita 11002 San Josecito 11003 San Antonio 11004 Concepción 11005 San Felipe 111 CANTON CORONADO -

Cultural Heritage Within Environmental Impact Assessment

ICOMOS INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC SYMPOSIUM 2013 SAN JOSÉ, COSTA RICA TANGIBLE RISKS, INTANGIBLE OPPORTUNITIES: LONG-TERM RISK PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSES FOR THREATS TO CULTURAL HERITAGE 2013 THEME: REDUCING RISKS TO CULTURAL HERITAGE FROM UNCONTROLLED DEVELOPMENT IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD SOFIA AVGERINOU-KOLONIAS, MELVIN CAMPOS OCAMPO & GUILLERMO BARZUNA PÉREZ (EDITORS) EDITORIAL BOARD: JAMES K. REAP, AMEL CHABBI, PAMELA JEROME International Council on Monuments and Sites, ICOMOS. © 2015 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-2-918086-16-1 EAN 9782918086161 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system —except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper— without permission in writing from the publisher. Photos and images presented in the texts are the copyrights of the authors unless otherwise indicated. The opinions expressed in the articles do not commit ICOMOS in any way and are the sole responsibility of their authors. Henning Jensen-Pennington Rector, University of Costa Rica INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON MONUMENTS AND SITES Advisory and Executive Committee Meeting & Scientific Symposium 2013, San José, Costa Rica ICOMOS International Secretariat 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans, 94220 Charenton-le-Pont, France Gustavo Araoz President, ICOMOS Ofelia Sanou President, ICOMOS Costa Rica Pamela Jerome Scientific Council Officer Sofia Avgerinou-Kolonias & Gisle Jakhelln Symposium Co-Chairs Main Editors: Sofia Avgerinou-Kolonias, Melvin Campos Ocampo & Guillermo Barzuna Pérez. English Editor for Theme I: James K. Reap. English Editor for Theme II: Amel Chabbi. -

Entrega De Paquetes 2021

NOMBRE PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO 12 DE MARZO DE 1948 SAN JOSE PEREZ ZELEDON SAN ISIDRO DE EL GENERAL 20 DE MARZO DE 1856 GUANACASTE NICOYA NICOYA 23 DE MAYO PUNTARENAS COTO BRUS LIMONCITO 25 DE JULIO GUANACASTE NICOYA SAN ANTONIO 26 DE FEBRERO DE 1886 GUANACASTE HOJANCHA MATAMBU 27 DE ABRIL GUANACASTE SANTA CRUZ VEINTISIETE DE ABRIL LA FLORIDA PUNTARENAS OSA PIEDRAS BLANCAS ABANGARITOS PUNTARENAS PUNTARENAS MANZANILLO ABELARDO ROJAS QUESADA ALAJUELA SAN CARLOS LA PALMERA ABRAHAM LINCOLN SAN JOSE ALAJUELITA ALAJUELITA ABRAHAM PANIAGUA NUÑEZ ALAJUELA SAN RAMON SAN ISIDRO ABRAHAN FARAH MATA GUANACASTE NANDAYURE ZAPOTAL ABROJO GUAYMI PUNTARENAS CORREDORES CORREDOR ACAPULCO PUNTARENAS PUNTARENAS ACAPULCO ACAPULCO ALAJUELA SAN CARLOS POCOSOL ACOYAPA GUANACASTE NICOYA MANSION ADELA RODRIGUEZ VENEGAS SAN JOSE MORA GUAYABO ADELE CLARINI PUNTARENAS COTO BRUS SAN VITO ADOLFO BERGER FAERRON GUANACASTE BAGACES MOGOTE AEROPUERTO ALAJUELA ALAJUELA RIO SEGUNDO AFRICA LIMON GUACIMO GUACIMO AGRIMAGA LIMON GUACIMO RIO JIMENEZ AGUA AZUL ALAJUELA SAN CARLOS LA FORTUNA AGUA BLANCA SAN JOSE ACOSTA PALMICHAL AGUA CALIENTE GUANACASTE BAGACES BAGACES AGUA CALIENTE GUANACASTE LA CRUZ SANTA ELENA AGUA CALIENTE GUANACASTE CAÑAS PALMIRA AGUA FRÍA LIMON POCOCI ROXANA AGUAS BUENAS SAN JOSE PEREZ ZELEDON PLATANARES AGUAS CALIENTES PUNTARENAS COTO BRUS PITTIER AGUAS FRESCAS PUNTARENAS OSA PUERTO CORTES AGUAS FRÍAS LIMON POCOCI ROXANA AGUAS NEGRAS ALAJUELA LOS CHILES CAÑO NEGRO AGUAS ZARCAS LIMON LIMON MATAMA AGUSTIN SEGURA SAN JOSE DESAMPARADOS SAN MIGUEL AJUNTADERAS -

2010 Death Register

Costa Rica National Institute of Statistics and Censuses Department of Continuous Statistics Demographic Statistics Unit 2010 Death Register Study Documentation July 28, 2015 Metadata Production Metadata Producer(s) Olga Martha Araya Umaña (OMAU), INEC, Demographic Statistics Unit Coordinator Production Date July 28, 2012 Version Identification CRI-INEC-DEF 2010 Table of Contents Overview............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Scope & Coverage.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Producers & Sponsors.........................................................................................................................................5 Data Collection....................................................................................................................................................5 Data Processing & Appraisal..............................................................................................................................6 Accessibility........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Rights & Disclaimer........................................................................................................................................... 8 Files Description................................................................................................................................................ -

Meinstructcodificayvalidaenaho2

Trabajo de Campo Transfiere Proceso de Calidad Envía Codificación 1. Empresas 4. Empleo 2. Geográfico 3. Educación de internet principal 6. Personas 5. Empleo desempleadas secundario Envía Validación 1. Verificación de 3. Revisión Final 2. Inconsistencias Codificación Envía 4. Chequeo de inconsistencias por parte del personal encargado Base ENAHO importación de o o o o o o o Sección (21) División (88) Grupo (238) Clase (419) Subclase (485) o o o o o o o o o G o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o SAN JOSÉ CANTÓN 108 Goicoechea CANTÓN 118 Curridabat CANTÓN 204 San Mateo CANTÓN 211 Zarcero CANTÓN 303 La Unión CANTÓN 403 Santo Domingo CANTÓN 503 San Cruz PUNTARENAS CANTÓN 101 San José 01 Guadalupe 01 Curridabat 01 San Mateo 01 Zarcero 01 Tres Ríos 01 Santo Domingo 01 Santa Cruz CANTÓN 601 Puntarenas CANTÓN 609 Parrita 01 Carmen 02 San Francisco 02 Granadilla 02 Desmonte 02 Laguna 02 San Diego 02 San Vicente 02 Bolsón 01 Puntarenas 01 Parrita 02 Merced 03 Calle Blancos 03 Sánchez 03 Jesús María 03 Tapesco 03 San Juan 03 San Miguel 03 Veintisiete de Abril 02 Pitahaya 03 Hospital 04 Mata de Plátano 04 Tirrases 04 Labrador 04 Guadalupe 04 San Rafael 04 Paracito 04 Tempate 03 Chomes CANTÓN 610 Corredores 04 Catedral 05 Ipis 05 Palmira 05 Concepción 05 Santo Tomás 05 Cartagena 04 Lepanto 01 Corredor 05 Zapote 06 Rancho Redondo CANTÓN 119 Perez Zeledón CANTÓN 205 Atenas 06 Zapote 06 Dulce Nombre 06 Santa Rosa 06 Cuajiniquil 05 Paquera 02 -

Letter Post Compendium Costa Rica

Letter Post Compendium Costa Rica Currency : colon costarricense Basic services Mail classification system (Conv., art. 17.4; Regs., art. 17-101) 1 Based on speed of treatment of items (Regs., art. 17-101.2: Yes 1.1 Priority and non-priority items may weigh up to 5 kilogrammes. Whether admitted or not: No 2 Based on contents of items: No 2.1 Letters and small packets weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. 17-103.2.1). Whether admitted or not No (dispatch and receipt): 2.2 Printed papers weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. 17-103.2.2). Whether admitted or not for No dispatch (obligatory for receipt): 3 Classification of post items to the letters according to their size (Conv., art. 17,art. 17-102.2) Yes Optional supplementary services 4 Insured items (Conv., art. 18.2.1; Regs., 18-001.1) 4.1 Whether admitted or not (dispatch and receipt): No 4.2 Whether admitted or not (receipt only): No 4.3 Declaration of value. Maximum sum 4.3.1 surface routes: No limits 4.3.2 air routes: No limits 4.3.3 Labels. CN 06 label or two labels (CN 04 and pink "Valeur déclarée" (insured) label) used: - 4.4 Offices participating in the service: - 4.5 Services used: 4.5.1 air services (IATA airline code): CM Copa airlines / IB Iberia / AA American Airlines 4.5.2 sea services (names of shipping companies): N/A 4.6 Office of exchange to which a duplicate CN 24 formal report must be sent (Regs., art.17-138.11): Office Name : CTP / Centro Tratamiento Postal / Módulo Archivo Office Code : CTP / Mod Archivo Address : Zapote de la Iglesia católica 200 mts sur, Centro Tratamiento Postal - Mod de Documentación Phone : 22022900 Fax : E-mail 1 : [email protected] E-mail 2: [email protected] 5 Cash-on-delivery (COD) items (Conv., art. -

Análisis Cantón De Esparza

Febrero 2020 Análisis Cantón de Esparza Estrategia Integral de Prevención para la Seguridad Pública Análisis Cantonal Esparza Estrategia Integral de Prevención para la Seguridad Pública Índice Introducción ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Objetivo General ................................................................................................................................ 3 Marco referencial ............................................................................................................................ 4 Teoría General de los Sistemas ..................................................................................................... 4 Teoría de las percepciones sociales ............................................................................................ 5 Teoría del valor público ................................................................................................................... 6 Antecedentes ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Histograma de tendencia en denuncias por delitos contra la propiedad. ............................................ 10 Gráfico 1. Gráfico lineal ................................................................................................................. 11 Despliegue Metodológico ..............................................................................................................