We Believe in Being Honest: Dependency Exemptions for LDS Missionaries Annalee Hickman Moser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

BUILDING THE LATTER-DAY KINGDOM IN THE AMERICAS: THE FLORIDA FORT LAUDERDALE MISSION By GAYLE LASATER PAGNONI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Gayle Lasater Pagnoni 2 To Lou, Dirk and Gracie, and Drew 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without my advisers at the University of Florida including my supervisor, Anna Peterson, and committee members, David Hackett, Whitney Sanford, and Marianne Schmink. These four scholars and four important communities are among those I remember as instrumental to my completion of the doctoral degree: the academic community at the University of Florida (UF); Florida International University (FIU); the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and its Florida Fort Lauderdale Mission (FFLM); and my loved ones. At UF, I thank those pioneers in our department who envisioned a new doctoral program organized to innovatively think about the study of religion through three tracks: Religion in the Americas, Asian Religions, and Religion and Nature. My interests have always been religion and politics in the Americas, with interests in the environment so this program was a good fit. Second, I thank the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences for awarding to me the Aschoff Dissertation Writing Award, and to the Madelyn Lockhart Dissertation Fellowship Committee for choosing me as a finalist. Both awards facilitated my research and writing. I am most indebted to Dr. Anna Peterson, University of Florida Latin Americanist, environmentalist, and ethicist, as chair of my dissertation committee, teaching supervisor, and mentor extraordinaire. -

Newsletter 2016

Brigham Young University 2016 History Department Newsletter Artist: Thomas Cole, see page 15 for details In this Issue: 3 The Rewards of Memoir as a View of Research by Dr. our Journey Patrick Mason By Ignacio M. García 4 A Message from the Department Years ago I saw a New Yorker cartoon in which Chair a little girl sat on her bed with a typewriter and in the page she had written, “In my years 5 Lecture Spotlight of life I…” The cartoon mocked the prolifer- ation of memoirs by people who had done 6 Family History nothing of any merit. That era was followed by Updates another, still with us today, in which memoir seems to be about how well you can put togeth- 8 New Faculty er a phrase, sentence, paragraph, chapter, etc. —but, again, too rarely about something significant. So, when I de- 9 Faculty News cided to write my own memoir I thought about it for quite a while. There were the usual reasons for seeking to write one but none of them 13 Faculty seemed important enough to kill another tree or fill another bookshelf until I Recommended realized that as a Chicano Mormon activist historian I needed to explain my- Readings self to those who read and taught my work. For years I was seen as an enig- ma in both the Chicano scholarship community and among some of my 14 Artwork in the Mormon friends and colleagues. It was hard for either to understand why I be- Halls of the longed to the “other” even though for me it seemed natural to belong to both. -

BYU-Hawaii Magazine, Winter 2005

Special Issue Commemorates 50th Anniversary Celebration Table of Contents Features Aloha and mahalo Jubilee! 2 A Stellar Week of Celebration Gladys Knight Sets the Pace 6 for a Golden Jubilee! Singer Unites Many Cultures in Celebration EXECUTIVE EDITOR On the Shoulders of Giants 10 V. Napua Baker , V.P. for University Advancement President Shumway Honors His Predecessors Genuine Gold 13 EDITOR Honored Alumni Representatives Rob Wakefield , Director of Communications fter months and months of anticipation and Evening of Memories 14 CONTRIBUTING EDITOR effort, it is hard to believe that BYU-Hawai‘i’s Vernice Weneera , Director of The Pacific Institute Golden Jubilee celebration of 2005 is now Hawai‘i Governor Linda Lingle 17 Abehind us. I’m not sure that I’ve ever experienced any - Delivers Keynote Address thing quite as perfect as our Jubilee Week. WRITERS Children Commemorate 1921 Flag Raising 18 Mike Foley With the attitude that they were going to produce Andrew Miller something magnificent, everybody worked together in Jubilee Ball 20 Amanda Beard incredible unity, laboring day and night, and doing it Elder Robert Parchman with the most wonderful harmony. There were no Honolulu Mayor Mufi Hannemann 22 Justin Smith glitches, no arguments, we just did it together. Gladys Addresses Special Luncheon for President Monson Scott Christley Knight and her choir, the Evening of Reminiscences, the landmark speeches by Hawai‘i Governor Linda Lingle and Honolulu Mayor Mufi Hannemann, the ART DIRECTOR Fine Arts ExtravaganZa, and so many other moments Anthony Perez , University Communications comprised a week we will never forget. And we can indeed go forward. -

Grateful Intern Returns Home, P. 1 BYU–Hawaii: the Charted Course, P

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY HAWAII | POLYNESIAN CULTURAL CENTER Grateful intern returns home, p. 1 BYU–Hawaii: The charted course, p. 2 The importance of internships, p. 3 Radiating aloha, p. 13 PCC: Advancing the work, p. 15 FALL 2008 table OF CONTENTS 2 | BYU–Hawaii: The charted course 3 | Prepare for tomorrow by interning today 5 | Than Lim—a Cambodian student’s journey 6 | Alumni demonstrate entrepreneurial spirit 7 | New BYU–Hawaii President’s Council in place 3 10 9 | Distance learning: Taking BYU–Hawaii to the world 10 | Needed makeover approved for campus backyard 11 | New year-round calendar begins in January 13 | Radiating aloha, miracles at PCC 15 | PCC: Advancing the work 6 16 | Teaching hula to speakers of other languages 17 | Iosepa's new home 19 | Campus department focuses on careers and alumni 21 | CCH alumni reunite on campus 22 | Fulisia Saleuesile—a case for BYU–Hawaii 15 14 ON THE cover Intern conducts research, identifies life’s goals Last summer Ting-Ning Pao Fowers interned in the molecular medicine department of her native Taiwan’s National Cheng Kung Medical University. “My internship broadened my knowl- “I’m indeed very grateful for my China both have developing biotechnol- edge and gave me a chance to do research internship and all those who helped me ogy industries, and I’d like to be involved,” beyond what I would ever get to do at along the way,” she says. she says. school. It helped me see where I want to Currently she is working on her go, to set goals for my life,” says Fowers. -

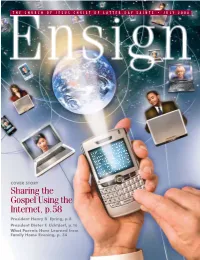

July 2008 Ensign

THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2008 COVER STORY Sharing the Gospel Using the Internet, p.58 President Henry B. Eyring, p.8 President Dieter F. Uchtdorf, p.16 What Parents Have Learned from Family Home Evening, p. 34 COURTESY OF RIVER MILLS FINE ART Nauvoo Temple, by Myron R. Goodwin The Nauvoo Illinois Temple was built upon the site of the original Nauvoo Temple. President Gordon B. Hinckley dedicated the new temple on June 27, 2002, praying that it would stand as a memorial to the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, who were martyred in 1844. JULY 2008 Contents VOLUME 38 • NUMBER 7 Over the years, scien- tific evidence has favored a diet consis- tent with the principles of the Word of Wisdom. See “Cancer, Nutrition, and the Word of Wisdom: One Doctor’s Observations,” p. 42. THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2008 COVER STORY Sharing the Gospel Using the Internet, p.58 President Henry B. Eyring, p.8 President Dieter F. Uchtdorf, p.16 What Parents Have Learned from Family Home Evening, p. 34 4 8–21 ON THE COVER MESSAGES FEATURE ARTICLES Illustration by Cary Henrie FIRST PRESIDENCY President Henry B. Eyring: Called of God MESSAGE 8 ELDER ROBERT D. HALES Heeding the Voice A biographical sketch of the First Counselor 4 of the Prophet in the First Presidency. PRESIDENT DIETER F. UCHTDORF President Dieter F. Uchtdorf: A Family Man, In our Father’s great love for 16 a Man of Faith, a Man Foreordained us, He has given us prophets ELDER RUSSELL M. -

Answering the Call Page 14 LDS Philanthropies at BYU-Idaho Page

Answering the Call Page 14 LDS Philanthropies at BYU-Idaho Page 20 Merely a Teacher Page 28 [ ] f a l l 2 0 0 5 s u m m i t Contents 7 8 12 20 24 7 the web counts 18 Continuing the Tradition: What started out as a class experiment has grown into a LDS Philanthropies vital communication tool to stay connected with the school. Tithes and offerings contribute greatly to BYU–Idaho, but Preview a sampling of what’s in store for your next visit to additional philanthropic gifts extend the blessings even www.byui.edu. more. Discover what a difference philanthropy makes in the lives of students and those who donate. 8 Rethinking Education: Harvesting Dreams Learn what’s new in the realigned College of Agriculture 4 Merely a Teacher and Life Sciences as each of the six departments describes How much can a teacher really affect a student’s life? See unique changes and refocused efforts to help students. how one professor views her experiences and the lessons she hopes her students will come to understand. 1 Answering the call Meet the fifteenth president to head the campus on the hill. departments Kim B. Clark is welcomed at BYU–Idaho and resolves to 3 Letter from the President continue the steady, upward course. 4 From the Mailbag 5 Alumni News 8 News of Note 30 Alumni Portfolio 31 Alumni Awards publisher/alumni director student designers alumni association president alumni council members SUMMIT MAGAZINE is published by the Steven J. Davis ’84 Brandt Brinkerhoff Joe Marsden ’75 Sid ’83 and Ann Wray Ahrendsen ’83 BYU–Idaho/Ricks College Alumni Association alumni relations officer Christopher Grayson alumni association president-elect Louise Blunck Benson ’73 twice a year. -

DIALOGUE DIALOGUE PO Box 381209 Cambridge, MA 02238 Electronic Service Requested

DIALOGUE DIALOGUE PO Box 381209 Cambridge, MA 02238 electronic service requested DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought 49.1 spring 2016 49.1 EDITORS EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT FICTION Julie Nichols, Orem, UT DIALOGUE POETRY Darlene Young, South Jordan, UT a journal of mormon thought REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand Carter Charles, Bordeaux, France POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT IN THE NEXT ISSUE PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT ART Andrea Davis, Orem, UT Michael Barker, Daniel Parkinson, and Benjamin Brad Kramer, Murray, UT Knoll look at suicide rates among gay LDS teens BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF BUSINESS MANAGER Mariya Manzhos, Cambridge, MA A roundtable discussion on Exponent II with Claudia PRODUCTION MANAGER Jenny Webb, Huntsville, AL Bushman, Nancy Tate Dredge, Judy Dushku, Susan COPY EDITORS Jani Fleet, Taylorsville, UT Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI Whitaker Kohler, and Carrel Hilton Sheldon INTERNS Geoff Griffin, Provo, UT Ian Mounteer, Orem, UT And fiction from Levi Peterson and Eric Jepson Christian D. Van Dyke, Provo, UT EDITORIAL BOARD Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Mathew Schmalz, Worcester, MA Ignacio M. Garcia, Provo, UT David W. Scott, Lehi, UT Brian M. Hauglid, Spanish Fork, UT John Turner, Fairfax, VA G. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 3, Summer 2010

Journal of Mormon History Volume 36 Issue 3 Summer 2010 Article 1 2010 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 3, Summer 2010 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 36, Summer 2010: Iss. 3. This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 3, Summer 2010 Table of Contents LETTERS --External Reviewers AWOL? Armand L. Mauss, vii --Brandon Morgan Responds Brandon Morgan, viii --Small Arms Fire William P. MacKinnon, ix --Utah Coal J. Clifford Jones, xi --Actions Paint a Portrait Will Bagley, xii ARTICLES --Materialism and Mormonism: The Early Twentieth-Century Philosophy of Dr. John A. Widtsoe Clyde D. Ford, 1 --Helvécio Martins: First Black General Authority Mark L. Grover, 27 --“A P.O. Box and a Desire to Witness for Jesus”: Identity and Mission in the Ex-Mormons for Jesus/Saints Alive in Jesus, 1975–90 Sara M. Patterson, 54 --Jefferson Hunt: California’s First Mormon Politician Tom Sutak, 82 --Search for Sources for Wilford Woodruff’s Idaho “Wagon Box Prophecy,” 1884 Mary Jane Fritzen, 118 --Joseph Smith and the Development of Habeas Corpus in Nauvo, 1841–44 John S. Dinger, 135 --Joseph Smith as Guardian: The Lawrence Estate Case Gordon A. Madsen, 172 REVIEWS --Mari Graña. Pioneer, Polygamist, Politician: The Life of Dr. -

Die Ansprachen Der Generalkonferenz

KIRCHE JESU CHRISTI DER HEILIGEN DER LETZTEN TAGE • MAI 2019 Die Ansprachen der Generalkonferenz Präsident Nelson fordert die Familien auf, die Erhöhung anzustreben Neue Generalautorität- Siebziger und neue Präsidentschaft der Sonntagsschule bestätigt 8 neue Tempel angekündigt, Tempel aus der Zeit der Pioniere werden renoviert DIE ERSTE PRÄSIDENTSCHAFT UND DAS KOLLEGIUM DER ZWÖLF APOSTEL IMBESUCHERZENTRUMDESROM- DER ZWÖLF KOLLEGIUM DIE ERSTEPRÄSIDENTSCHAFT UNDDAS TEMPELS „Vor über 2000 Jahren wirkte unser Erretter, Jesus Christus, unter den Menschen, richtete seine Kirche auf und verkündete sein Evangelium. Er berief Apostel und trug ihnen auf: ‚Darum geht und macht alle Völker zu meinen Jüngern.‘ [Matthäus 28:19.] In unserer Zeit ist die Kirche des Herrn wiederhergestellt worden. Der Erretter steht an der Spitze der Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage. Als neuzeitliche Apostel Jesu Christi verkünden wir die gleiche Botschaft wie die Apostel vor alters, nämlich dass Gott lebt und dass Jesus der Messias ist.“ – Präsident Russell M. Nelson bei seinem Besuch in Italien anlässlich der Weihung des Rom- Tempels im März Inhalt Mai 2019 145. Jahrgang • Nummer 5 Versammlung am Samstagvormittag 31 Durch den Geist nach Erkenntnis 67 Wir können besser handeln und 6 Wie kann ich es verstehen? trachten besser sein Elder Ulisses Soares Elder Mathias Held Präsident Russell M. Nelson 9 Sorgsam oder sorglos 34 Mit gläubigem Auge Versammlung am Sonntagvormittag Becky Craven Elder Neil L. Andersen 70 Vielfacher Segen 11 Antworten auf das Gebet 38 Sich an den Worten Christi weiden Elder Dale G. Renlund Elder Brook P. Hales Elder Takashi Wada 73 Christus – das Licht, das in der 15 Missionsarbeit – sagen Sie, was Ihr 41 Gottes Stimme hören Finsternis leuchtet Herz bewegt Elder David P. -

Generalkonferencetaler

JESU KRISTI KIRKE AF SIDSTE DAGES HELLIGE • MAJ 2019 Generalkonferencetaler Præsident Nelson opfordrer familier til at søge ophøjelse Nye generalautoriteter og halvfjerdsere og nyt hovedpræsidentskab for Søndagsskolen opretholdt 8 nye templer bekendtgjort, templer fra pionertiden skal renoveres DET FØRSTE PRÆSIDENTSKAB OG DE TOLV APOSTLES KVORUM IBESØGSCENTRET VEDTEMPLETIROM. APOSTLES KVORUM DET FØRSTEPRÆSIDENTSKAB OGDETOLV »For over 2.000 år siden betjente vor Frelser, Jesus Kristus, verden, etablerede sin kirke og sit evangelium. Han kaldte apostle og befalede dem: ›Gå derfor hen og gør alle folkeslagene til mine disciple‹ (Matt 28:19). I vore dage er Herrens kirke blevet gengivet. Frelseren står i spidsen for Jesu Kristi Kirke af Sidste Dages Hellige. Som Jesu Kristi apostle i vore dage bringer vi det samme budskab i dag, som apostlene fortalte for længe siden – at Gud lever, og at Jesus er Kristus.« – Præsident Russell M. Nelson, da han var i Italien til indvielsen af templet i Rom i marts. Indhold maj 2019 Årgang 168 • Nr. 5 Mødet lørdag formiddag 31 Søg kundskab ved Ånden Mødet søndag formiddag 6 Hvordan kan jeg forstå? Ældste Mathias Held 70 Rig på velsignelse Ældste Ulisses Soares 34 Troens øje Ældste Dale G. Renlund 9 Omhyggelig versus overfladisk Ældste Neil L. Andersen 73 Kristus: Lyset, der skinner i mørket Becky Craven 38 Tag for jer af Kristi ord Sharon Eubank 11 Svar på bønner Ældste Takashi Wada 76 Stor kærlighed til vor Faders børn Ældste Brook P. Hales 41 Hør hans røst Ældste Quentin L. Cook 15 Missionering: Del, hvad I har Ældste David P. Homer 81 Forberedelse til Herrens på hjerte 44 Se, dér er Guds lam tilbagekomst Ældste Dieter F. -

FROM ONLINE to on CAMPUS Page 4

PRESIDENT’S BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY–HAWAII 2015–16 FROM ONLINE TO ON CAMPUS Page 4 New Beginnings New president John S. Tanner builds on firm foundations page 3 Prophetic Destiny Book chronicles first 60 years of BYU–Hawaii page 6 FUNDRAISING REPORT 17% TRUSTEES AND PRESIDENT’S FUND MAHALO FOR YOUR 77% STUDENT AID GENEROSITY! including I-WORK, PCC work-study opportunities, scholarships, and You are accelerating the work of internship assistance 6% BYU–Hawaii. In 2014 donor support PROGRAMS AND CENTERS was allocated to the following: such as BYU–Hawaii Online and the Center for Learning and Teaching 1in5 90% 100% current students receive I-WORK funding. of the I-WORK program is funded by donor of your donation goes toward supporting Your donations provided educational contributions. I-WORK and other student- BYU–Hawaii and its students. Whether you opportunities and enhanced the BYU– aid programs remain our largest fundrais- choose to give to a specific program, such Hawaii experience for these students; ing priority. Our goal is to fund the I-WORK as I-WORK, or without restriction to the many of them would not be able to attend program entirely by donor contributions, Trustees and President’s Fund, no amount without your support. and the program is growing as we enroll of any donation is used to cover fundrais- more international students. ing expenses. Your donations to BYU–Hawaii bless students THANKS FOR GIVING! and assist the university in fulfilling its mission. President’s Report spotlights people and accomplishments related to fundraising at Brigham Young University– Editor in Chief Photographer Hawaii. -

70 TEMPORAL and SPIRITUAL SELF-RELIANCE: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and Development in the South Pacific Pa

sites: new series · vol 16 no 1 · 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11157/sites-id429 – article – TEMPORAL AND SPIRITUAL SELF-RELIANCE: The ChurCh of Jesus ChrIsT of Latter-daY saInTs and deveLopmenT In The souTh paCIfic Paul Morris1 aBsTraCT The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church, aka, the Mor- mons) plays a significant but largely neglected role in the literature on develop- ment in the Pacific. The aim of this paper is to address this lacuna and highlight the distinctive LDS theology of development without which their development agendas make little sense. The Pacific is pivotal to the LDS Church’s global mis- sion where its commitments to development, and emergency relief, have since the 1980s been increasingly understood in terms of an overarching theology of ‘self-reliance’, explored here both theologically and as specifically applied in the Pacific. Two main arguments are advanced in this article. First, the LDS Church’s development programmes in the Pacific have led to a re-articulation of their self-understanding and rationale and a recalibration of their Church’s priorities regionally and beyond. Second, while it often seems that Mormons are wedded to the capitalist system, this is recent and they are equally heirs to another model of ‘economic or gospel communalism’, and that the retrieval of this tradition is consistent with the Church’s priorities for the Pacific and a growing concern there. Keywords: Christianity; development; Mormons; Pacific Islands; self-reliance InTroduCTIon At a conference in Suva on religion and development in the Pacific in 20162 the chasm between our luxury hotel and the nearby shanty we visited, and the water bottling plant for export and the broken sewer main nearby, became in- creasingly evident.