2012–Monumentality, Formal Processes, Brahms Piano Cto. No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

50Th Annual Concerto Concert

SCHOOL OF ART | COLLEGE OF MUSICAL ARTS | CREATIVE WRITING | THEATRE & FILM BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY 50th a n n u a l c o n c e r t o concert BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY Summer Music Institute 2017 bgsu.edu/SMI featuring the SESSION ONE - June 11-16 bowling g r e e n Double Reed Strings philharmonia SESSION TWO - June 18-23 emily freeman brown, conductor Brass Recording Vocal Arts SESSION THREE - June 25-30 Musical Theatre saturday, february 25 Saxophone 2017 REGISTRATION OPENS FEBRUARY 1ST 8:00 p.m. For more information, visit BGSU.edu/SMI kobacker hall BELONG. STAND OUT. GO FAR. CHANGING LIVES FOR THE WORLD.TM congratulations to the w i n n e r s personnel of the 2016-2 017 Violin I Bass Trombone competition in music performance Alexandria Midcalf** Nicholas R. Young* Kyle McConnell* Brandi Main** Lindsay W. Diesing James Foster Teresa Bellamy** Adam Behrendt Jef Hlutke, bass Mary Solomon Stephen J. Wolf Morgan Decker, guest Ling Na Kao Cameron M. Morrissey Kurtis Parker Tuba Jianda Bai Flute/piccolo Diego Flores La Le Du Alaina Clarice* undergraduate - performance Nia Dewberry Samantha Tartamella Percussion/ Timpani Anna Eyink Michelle Whitmore Scott Charvet* Stephen Dubetz, clarinet Keisuke Kimura Jerin Fuller+ Elijah T omas Oboe/Cor Anglais Zachary Green+ Michelle Whitmore, flute Jana Zilova* Febe Harmon Violin II T omas Morris David Hirschfeld+ Honorable Mention: Samantha Tartamella, flute Sophia Schmitz Mayuri Yoshii Erin Reddick+ Bethany Holt Anthony Af ul Felix Reyes Zi-Ling Heah Jamie Maginnis Clarinet/Bass clarinet/ Harp graduate - performance Xiangyi Liu E-f at clarinet Michaela Natal Lindsay Watkins Lucas Gianini** Keyboard Kenneth Cox, flute Emily Topilow Hayden Giesseman Paul Shen Kyle J. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

Armida Abducts the Sleeping Rinaldo”

“Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo” Neutron autoradiography is capable of revealing different paint layers piled-up during the creation of the painting, whereas different pigments can be represented on separate films due to a contrast variation created by the differences in the half-life times of the isotopes. Thus, in many cases the individual brushstroke applied by the artist is made visible, as well as changes made during the painting process, so-called pentimentis. When investigating paintings that have been reliably authenticated, it is possible to identify the particular style of an artist. By an example - a painting from the French painter Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), belonging to the Berlin Picture Gallery - the efficiency of neutron autoradiography is demonstrated as a non- destructive method. Fig. 1: Nicolas Poussin, Replica, “Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo”, (c. 1637), Picture Gallery Berlin, 120 x 150 cm2, Cat No. 486 The painting show scenes from the bible and from classical antiquity. In 1625 the legend of the sorceress Armida and the crusader Rinaldo had inspired Poussin to a painting named “Armida and Rinaldo”, now owned by the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, that has been identified as an original. In contrast, the painting from the Berlin Picture Gallery “Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo” (Fig. 1) shows a different but similar scene, and was listed in the Berlin Gallery’s catalogue as a copy. To clarify the open question of the ascription a neutron radiography investigation was carried out. In Fig. 2, one of the autoradiographs is depicted. Fig. 2: Nicolas Poussin, “Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo”, 1st neutron autoradiography assembled from 12 image plate records: in order to investigate the whole picture, two separated irradiations were carried out and finally recomposed. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Violinist Julia Fischer Joins the Cso and Riccardo Muti for June Subscription Concerts at Symphony Center

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: June 13, 2016 Eileen Chambers, 312-294-3092 Photos Available By Request [email protected] NUVEEN INVESTMENTS EMERGING ARTIST VIOLINIST JULIA FISCHER JOINS THE CSO AND RICCARDO MUTI FOR JUNE SUBSCRIPTION CONCERTS AT SYMPHONY CENTER June 16 – 21, 2016 CHICAGO—Internationally acclaimed violinist Julia Fischer returns to Symphony Center for subscription concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) led by Music Director Riccardo Muti on Thursday, June 16, at 8 p.m., Friday, June 17, at 1:30 p.m., Saturday, June 18, at 8 p.m., and Tuesday, June 21, at 7:30 p.m. The program features Brahms’ Serenade No. 1 and Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major with Fischer as soloist. Fischer’s CSO appearances in June are endowed in part by the Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Fund, which is committed to nurturing the next generation of great classical music artists. Julia Fischer joins Muti and the CSO for Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Widely recognized as the first “Romantic” concerto, Beethoven’s lush and virtuosic writing in the work opened the traditional form to new possibilities for the composers who would follow him. The second half of the program features Brahms’ Serenade No. 1. Originally composed as chamber music, Brahms later adapted the work for full orchestra, offering a preview of the rich compositional style that would emerge in his four symphonies. The six-movement serenade is filled with lyrical wind and string passages, as well as exuberant writing in the allegro and scherzo movements. German violinist Julia Fischer won the Yehudi Menuhin International Violin Competition at just 11, launching her career as a solo and orchestral violinist. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto”

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto” I believe that one of the most rewarding aspects of life is exploring and discovering the magic and mysteries held within our universe. For a composer this thrill often takes place in the writing of a concerto…it is the exploration of an instrument’s world, a journey of the imagination, confronting and stretching an instrument’s limits, and discovering a particular performer’s gifts. The first movement of this concerto, written for the violinist, Hilary Hahn, carries a somewhat enigmatic title of “1726”. This number represents an important aspect of such a journey of discovery, for both the composer and the soloist. 1726 happens to be the street address of The Curtis Institute of Music, where I first met Hilary as a student in my 20th Century Music Class. An exceptional student, Hilary devoured the information in the class and was always open to exploring and discovering new musical languages and styles. As Curtis was also a primary training ground for me as a young composer, it seemed an appropriate tribute. To tie into this title, I make extensive use the intervals of unisons, 7ths, and 2nds, throughout this movement. The excitement of the first movement’s intensity certainly deserves the calm and pensive relaxation of the 2nd movement. This title, “Chaconni”, comes from the word “chaconne”. A chaconne is a chord progression that repeats throughout a section of music. In this particular case, there are several chaconnes, which create the stage for a dialog between the soloist and various members of the orchestra. The beauty of the violin’s tone and the artist’s gifts are on display here. -

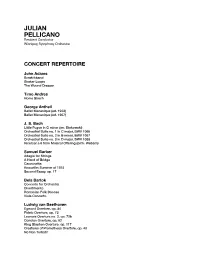

Julian Pellicano Repertoire Copy

JULIAN PELLICANO Resident Conductor Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra CONCERT REPERTOIRE John Adams Scratchband Shaker Loops The Wound Dresser Timo Andres Home Strech George Antheil Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1923) Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1957) J. S. Bach Little Fugue in G minor (arr. Stokowski) Orchestral Suite no. 1 in C major, BWV 1066 Orchestral Suite no. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067 Orchestral Suite no. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Ricercar a 6 from Musical Offering (orch. Webern) Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings A Hand of Bridge Canzonetta Knoxville: Summer of 1915 Second Essay, op. 17 Bela Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Divertimento Romanian Folk Dances Viola Concerto Ludwig van Beethoven Egmont Overture, op. 84 Fidelo Overture, op. 72 Leonore Overture no. 3, op. 72b Coriolan Overture, op. 62 KIng Stephen Overture, op. 117 Creatures of Prometheus Overture, op. 43 No Non Turbati! Octet, op. 103 Piano Concerti no. 1 - 5 Symphonies no. 1 - 9 Violin Concerto, op. 61 Alban Berg Drei Orchesterstucke, op. 6 Hector Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture Royal Hunt and Storm from Les Troyens Symphonie Fantastique, op. 14 Scene D’Amour from Romeo and Juliet Leonard Bernstein Overture to Candide On the Town: Three Dance Episodes Overture to WEst Side Story (ed. Peress) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Slava! Georges Bizet Carmen Suite no. 1 Carmen Suite no. 2 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 1 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 2 Alexander Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Polovtsian Dances Symphony no. 2 Johannes Brahms Academic Festival Overture, op. 80 Hungarian Dances no. 1,3,5,6,20,21 Symphonies no. -

Shepherd School Chamber Orchestra

RICE CHORALE THOMAS JABER , music director SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA LARRY RACHLEFF, music director THOMAS JABER, conductor Thursday, October 27, 1994 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall c~ RICE UNNERSITY SchOol Of Music PROGRAM Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny), Op. 54 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) You wander on high in light on ground that is soft, blessed spirits! Shining, godly zephyrs brush you as lightly as the player's fingers brush holy strings. Fateless, like sleeping infants, the Celestial breathe. They are chastely preserved in modest bud. In eternal blossom their spirit lives and their blissful eyes gaze in calm clarity. Yet to us is given no place to rest. They vanish, they fall, suffering mortals, blindly from one hour to the next, ,... • J like water flung from cliff to clifffor years down into the unknown. [Friedrich Holder/in] INTERMISSION Requiem, K. 626 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) .. edited by Richard Maunder I. Requiem aeternam Eternal rest grant them, 0 Lord; and may perpetual light shine upon them. A hymn, 0 God, becometh Thee in Sion, and a vow shall be paid to Thee in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer; to Thee all flesh shall come. Eternal rest, etc. Michelle Jockers, soprano II. Kyrie Lord, have mercy, Christ, have mercy, Lord, have mercy. III. Dies irae Day of wrath, that day shall dissolve the world into embers, as David prophesied with the Sibyl. How great the trembling will be, when the Judge shall come, the rigorous investigator of all things I IV. Tuba mirum The trumpet, spreading its wondrous sound through the tombs of every land, will summon all before the throne. -

Unknown Brahms.’ We Hear None of His Celebrated Overtures, Concertos Or Symphonies

PROGRAM NOTES November 19 and 20, 2016 This weekend’s program might well be called ‘Unknown Brahms.’ We hear none of his celebrated overtures, concertos or symphonies. With the exception of the opening work, all the pieces are rarities on concert programs. Spanning Brahms’s youth through his early maturity, the music the Wichita Symphony performs this weekend broadens our knowledge and appreciation of this German Romantic genius. Hungarian Dance No. 6 Johannes Brahms Born in Hamburg, Germany May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Germany Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria Last performed March 28/29, 1992 We don’t think of Brahms as a composer of pure entertainment music. He had as much gravitas as any 19th-century master and is widely regarded as a great champion of absolute music, music in its purest, most abstract form. Yet Brahms loved to quaff a stein or two of beer with friends and, within his circle, was treasured for his droll sense of humor. His Hungarian Dances are perhaps the finest examples of this side of his character: music for relaxation and diversion, intended to give pleasure to both performer and listener. Their music is familiar and beloved - better known to the general public than many of Brahms’s concert works. Thus it comes as a surprise to many listeners to learn that Brahms specifically denied authorship of their melodies. He looked upon these dances as arrangements, yet his own personality is so evident in them that they beg for consideration as original compositions. But if we deem them to be authentic Brahms, do we categorize them as music for one-piano four-hands, solo piano, or orchestra? Versions for all three exist in Brahms's hand.