Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Number Document Title Authors, Compilers, Or Editors Date

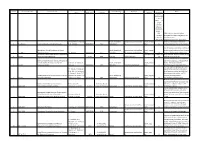

Authors, Compilers, or Date (M/D/Y), Location, Site, or Format/Copy/C Ensure Index # Document Number Document Title Status Markings Keywords Notes Editors (M/Y) or (Y) Company ondition Availability Codes: N=ORNL/NCS; Y=NTIS/ OSTI, J‐ 5700= Johnson Collection‐ ORNL‐Bldg‐ 5700; T‐ CSIRC= ORNL/ Nuclear Criticality Safety Thomas Group,865‐574‐1931; NTIS/OSTI is the Collection, DOE Information LANL/CSIRC. Bridge:http://www.osti.gov/bridge/ J. W. Morfitt, R. L. Murray, Secret, declassified computational method/data report, original, Early hand calculation methods to 1 A‐7.390.22 Critical Conditions in Cylindrical Vessels G. W. Schmidt 01/28/1947 Y‐12 12/12/1956 (1) good N estimate process limits for HEU solution Use of early hand calculation methods to Calculation of Critical Conditions for Uranyl Secret, declassified computational method/data report, original, predict critical conditions. Done to assist 2 A‐7.390.25 Fluoride Solutions R. L. Murray 03/05/1947 Y‐12 11/18/1957 (1), experiment plan/design good N design of K‐343 solution experiments. Fabrication of Zero Power Reactor Fuel Elements CSIRC/Electroni T‐CSIRC, Vol‐ Early work with U‐233, Available through 3 A‐2489 Containing 233U3O8 Powder 4/1/44 ORNL Unknown U‐233 Fabrication c 3B CSIRC/Thomas CD Vol 3B Contains plans for solution preparation, Outline of Experiments for the Determination of experiment apparatus, and experiment the Critical Mass of Uranium in Aqueous C. Beck, A. D. Callihan, R. Secret, declassified report, original, facility. Potentially useful for 4 A‐3683 Solutions of UO2F2 L. Murray 01/20/1947 ORNL 10/25/1957 experiment plan/design good Y benchmarking of K‐343 experiments. -

The New Yorker, March 9, 2015

PRICE $7.99 MAR. 9, 2015 MARCH 9, 2015 7 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 27 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Jeffrey Toobin on the cynical health-care case; ISIS in Brooklyn; Imagine Dragons; Knicks knocks; James Surowiecki on Greece. Peter Hessler 34 TRAVELS WITH MY CENSOR In Beijing for a book tour. paul Rudnick 41 TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE OF SEXUAL DIFFERENCE JOHN MCPHEE 42 FRAME OF REFERENCE What if someone hasn’t heard of Scarsdale? ERIC SCHLOSSER 46 BREAK-IN AT Y-12 How pacifists exposed a nuclear vulnerability. Saul Leiter 70 HIDDEN DEPTHS Found photographs. FICTION stephen king 76 “A DEATH” THE CRITICS A CRITIC AT LARGE KELEFA SANNEH 82 The New York hardcore scene. BOOKS KATHRYN SCHULZ 90 “H Is for Hawk.” 95 Briefly Noted ON TELEVISION emily nussbaum 96 “Fresh Off the Boat,” “Black-ish.” THE THEATRE HILTON ALS 98 “Hamilton.” THE CURRENT CINEMA ANTHONY LANE 100 “Maps to the Stars,” “ ’71.” POEMS WILL EAVES 38 “A Ship’s Whistle” Philip Levine 62 “More Than You Gave” Birgit Schössow COVER “Flatiron Icebreaker” DRAWINGS Charlie Hankin, Zachary Kanin, Liana Finck, David Sipress, J. C. Duffy, Drew Dernavich, Matthew Stiles Davis, Michael Crawford, Edward Steed, Benjamin Schwartz, Alex Gregory, Roz Chast, Bruce Eric Kaplan, Jack Ziegler, David Borchart, Barbara Smaller, Kaamran Hafeez, Paul Noth, Jason Adam Katzenstein SPOTS Guido Scarabottolo 2 THE NEW YORKER, MARCH 9, 2015 CONTRIBUTORS eric schlosser (“BREAK-IN AT Y-12,” P. 46) is the author of “Fast Food Nation” and “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety.” jeFFrey toobin (COMMENT, P. -

![Ludwig Von Mises, Socialism: an Economic and Sociological Analysis [1922]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7400/ludwig-von-mises-socialism-an-economic-and-sociological-analysis-1922-67400.webp)

Ludwig Von Mises, Socialism: an Economic and Sociological Analysis [1922]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Ludwig von Mises, Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis [1922] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

April 15, 1976

I April15,1976 / 3M * PEACE AND FREEDOM THRUI NONVIOLENT ACTION i fhe Farmworkers Want California's Farm Labor Board Back The Americanization of Cairo V¡olence in the Gay Subculture WRL's Annual Peace Award f;, ;. quite disturbed by Mart¡¡ good I'm Jezer's luck in reading it. Not all ofus that that your idea of an April Fool's Day 'review of the film Seven Bæntþc are interested in political struggles have connEcarcN [IVIN, 4/1/7ó] wg,leftthe Jbke to forset to credit the letter to me.. ' 3/ 4/ 761, which allows writer/director had a "good" education available to us. I¡¡tl¡¡ue [WIN' cccond lotler or just coin"cid ence? Vzway thru reading Lina Wirtmuller the title !'one of the I hope that people will become aware of wrlûert¡ n¡me oft the letter w¡¡ wrltlen by it itsounded familiat' great filmmakers of our tlme",though this use of classism anil try to do some- ¡bout votlnc. Ih¡t CNrv CohofNew Yernon, NJ, rndnot coLT "her woddview is one of relentless thing about it. DeYORE -.LAY -DIÄNA by úrn Uonrn er ono mlght guos. Helo New Yenron, NJ despair. powerful filmmakbr, yes, . (Xovolrndr0hlo ".A lc wh¡t Clrv wroto to u¡¡ We a¡rologlzo. It rr¡3 an oraori not o but geat? Radical folk have long recog- Dear WIN Friends (& influence Your Joke. -WIN nüed that science cannot be neutral; it neichbors), Thanks fo¡ Printing mY eithqr serves the ruling classes or it leftãr in your April lst l-sue' but was (Ictters contlnued on P¡ge 20.) Your teaders serves change. -

Extensions of Remarks

32254 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 23, 19 7 6 before the Senate, I move, in accordance CONFffiMATIONS ject to the nominee's commitment to respond with the previous order, that the Senate to requests to appear and testify before any Executive nominations confirmed by duly constituted committee of the Senate. stand in adjournment until the hour of the Senate September 23, 1976: THE JUDICIARY 9 a.m. tomorrow. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND Howard G. Munson, of New York, to be The motion was agreed to; and at 8: 03 WELFARE U.S. district judge for the northern district p.m., the Senate adjourned until tomor Susan B. Gordon, of New Mexico, to be an of New York. Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Vincent L. Broderick, of New York to be row, Friday, September 24, 1976, at 9 Welfare. U.S. district judge for the southern dtstrict a.m. The above nomination was approved sub- of New York. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE POLISH NATIONAL ALLIANCE Toastmaster, Felix Mika. attractive for advertisers to distribute their OF YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO Introduction of, Jack c. Hunter, Mayor, brochures unaddressed, as newspaper sup Youngstown, Ohio. • plements for instance, than to distribute Introduction of guests, Toastmaster. them separately to specific people or ad HON. CHARLES J. CARNEY Presentation of honoree, Mary C. Grabow dresses. OF 01!110 ski, Commissioner District 9, PNA. "Our members should be able to use pri Main speaker, Aloysius A. Mazewski, Presi vate delivery companies to deliver advertis IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES dent PNA. ing material just as can be done for maga Thursday, September 23, 1976 Presentation of deb't~tantes, Mary C. -

The Nuclear Resister“A Chronicle of Hope”

the Nuclear Resister “A Chronicle of Hope” No. 144 November 11, 2006 A Declaration of Peace Military Nonviolent Resistance Refusers Call for Public at Post-Occupation Peak Support In late September, the complimentary efforts of march around the Capitol and on to the Senate office Two more public military refusers are now in cus- the Declaration of Peace (DoP) campaign and the buildings. At the morning rally in Upper Senate Park, tody, while more AWOL refusers have publicly surren- National Campaign for Nonviolent Resistance (NCNR) Army veteran Ellen Barfield told the crowd, “We are here dered and await judgment combined to produce the greatest number of coordinated today to confront our dilatory Congress, who needs to get civil resistance actions resulting in arrest since the inva- a spine. And we hope to help them with that little prob- AWOL Iraq combat medic Sgt. Agustin Aguayo sion of Iraq in March, 2003. lem.” turned himself in at Fort Irwin, California on September 26, and within days was shipped to Germany, where his As an interfaith liturgy con- now-deployed Army unit is stationed. He is jailed pend- cluded, Capitol police told Max ing court martial. Aguayo’s application for conscientious Obuszewski of Baltimore, who objector status had been rejected and his unit was served on the NCNR permit commit- ordered to deploy again in early September when he tee, that no one would be allowed to slipped away from his home in Germany. He then march out of the Park without risking rejoined his wife and children in Los Angeles for a press arrest. -

The Nuclear Freeze Campaign and the Role of Organizers

Week Three Reading Guide: The Nuclear Freeze campaign and the role of organizers The reading by Redekop has been replaced by a book review by Randall Forsberg, and the long rough- cut video interview of Forsberg has been replaced by a shorter, more focused one. We start the first day with a brief discussion of Gusterson’s second article, building on the previous long discussion of the first one. September 23, 2019 Gusterson, H. 1999, “Feminist Militarism,” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 22.2, 17; https://doi.org/10.1525/pol.1999.22.2.17 This article focuses on the feminist themes Gusterson touched on in his earlier one. He begins restating the essentialist position and its opposition by feminists via “social constructedness.” Second-wave feminism started with Simone de Beauvoir’s idea that gender is constructed (“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”) and extending to post-structuralist Judith Butler, for whom gender is a performance, potentially fluid, learned and practiced daily based on cultural norms and discourses. Gusterson is intrigued by the idea of feminist militarism as performance. “If we weren’t feminists when we went in [to the military], we were when we came out.” What was meant by this? How does the military culture described in the article reflect gender essentialism? On p. 22, Gusterson argues that the women’s movement and the peace movement “remake their mythic narratives… through the tropes of revitalization.” What does he mean by this? Do you agree or disagree? Why? Is feminist militarism feminist? Does your answer depend on whether you adopt essentialist or constructivist reasoning? Wittner, L. -

Annual Giving

ANNUAL GIVING 2016-2017 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT GIVING IN REVIEW Dear Generous Benefactors, 2016 - 2017 It is my privilege to report on a few highlights of what your generosity enabled us to July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 accomplish this year. The 2016-17 annual giving year saw a few records set and many enhancements to the educational experience of our Dons. The Loyola Fund Unrestricted & Designated $2,227,693 33% I continue to be humbled by the extraordinary generosity that you bestow upon the Endowed Scholarship Gifts $1,562,963 49% Loyola Blakefield community. Leading the way in support of our mission not only Capital Projects Support $523,444 The Annual Fund invests in the formation of our Dons, but inspires others to follow in your charitable 11% Blue & Gold Auction - Net Proceeds $386,718 Endowed Scholarships footsteps. 7% Capital Projects Support Let’s continue to partner with one another to create more opportunities for our Dons $4,700,818 Blue & Gold Auction to grow in their faith, conquer intellectual pursuits, and learn the value of serving others. With gratitude, ALUMNI GIVING Mr. Anthony I. Day P ’15, ’19vt month TOTAL GIFTS* President JUNE OF ALL ALUMNI 17.4% MADE A GIFT TOP 5 CLASSES $4.7 participation dollars raised million 1953 71% 1978 $352,140 1947 & 1954 42% 1982 $177,599 1949 & 1955 38% 1963 $158,580 RECORD 1960 35% 1964 $121,922 LOYOLA FUND 1952 & 1965 33% 1957 $107,515 $2.6 million BREAKING campaignFAMILY GIVING YEAR FY FY FACULTY, STAFF, AND BOARD THANK YOU TO ALL OF OUR 2016 48% 55% 2017 OF TRUSTEES GIVING DONORS AND VOLUNTEERS PERCENT PARTICIPATION BY CLASS PARTICIPATION CLASS OF 2017 43% CLASS OF 2021 62% * Every effort has been made to include all donors to Loyola Blakefield whose gifts were CLASS OF 2018 47% CLASS OF 2022 73% received between July 1, 2016 and June 30, 2017. -

Homelessness a System Perspective

Homelessness A System Perspective Christian Seelos1 Global Innovation for Impact Lab, Stanford University PACS How to cite: Seelos, C (2021) Homelessness. A System Perspective (Part 1). Case Study_2021_001, Global Innovation for Impact Lab at Stanford PACS. 1 I am grateful to my colleagues Johanna Mair and Charlotte Traeger for joint interviews and reflection sessions throughout the work on this case study. Table of Contents Part 1 - The emergence of homelessness as a social problem The 1960s – Wars on poverty we can’t win… _____________________________________ 5 Contemporary frames of poverty __________________________________________________ 6 Challenges of addressing complex social problems ____________________________________ 6 The 1970s – Setting the course for homelessness _________________________________ 10 The undeserving poor: Framing the problem of homelessness __________________________ 10 A troubling situation but not a social problem _______________________________________ 12 The 1980s – Homelessness emerges as a social problem ___________________________ 14 Homeless numbers-games and convenient explanations ______________________________ 15 The awakening of homelessness activism ___________________________________________ 16 Radical activism _______________________________________________________________ 17 Research and documentation ____________________________________________________ 17 Litigation _____________________________________________________________________ 19 Dedicated organizations ________________________________________________________ -

Institute's History

1 History of the Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies By Ian Harris, Dick Ringler, Kent Shifferd, and William Skelton The Wisconsin Institute for the Study of the future League of Nations that were War, Peace, and Global Cooperation, designed to outlaw war. now the Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, began in the early Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), 1980s, a period of considerable peace including those in the peace movement, activity in the United States.1 Most were early advocates for peace specifically, in response to the education. Peace societies came breakdown of arms control talks and together at world peace conventions, the saber rattling by President Ronald first of which took place in The Hague, Reagan, a worldwide peace movement Netherlands, on May 18, 1899, a day had emerged, focusing on the thereafter commemorated as peace day proliferation of nuclear weapons and and celebrated on campuses and the heightened tensions of the Cold schools throughout the United States. War. In addition, U.S. involvement in In Wisconsin, there was considerable Central America had spawned various resistance to the First World War by the “cells” of nonviolent activists across the German settlers who did not want the United States who demonstrated United States to enter into war against against military oppression in Latin their “fatherland.” Much of the America and sent peace delegations to opposition also came from socialists countries like Guatemala, El Salvador, opposed to fighting “a rich man‟s war.” and Nicaragua. In a broader historical After World War I, peace activists and context, however, the formation of the educators promoted “education for Wisconsin Institute also reflected trends international understanding,” whose in the fields of peace studies, peace purpose was to humanize different education, and peace research that had cultures around the world so that they developed during the twentieth century. -

Burn It Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985

Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 by Eryk Martin M.A., University of Victoria, 2008 B.A. (Hons.), University of Victoria, 2006 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Eryk Martin 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Eryk Martin Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Title: Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 Examining Committee: Chair: Dimitris Krallis Associate Professor Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor Roxanne Panchasi Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Professor Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Joan Sangster External Examiner Professor Gender and Women’s Studies Trent University Date Defended/Approved: January 15, 2016 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This dissertation investigates the experiences of five Canadian anarchists commonly knoWn as the Vancouver Five, Who came together in the early 1980s to destroy a BC Hydro power station in Qualicum Beach, bomb a Toronto factory that Was building parts for American cruise missiles, and assist in the firebombing of pornography stores in Vancouver. It uses these events in order to analyze the development and transformation of anarchist activism between 1967 and 1985. Focusing closely on anarchist ideas, tactics, and political projects, it explores the resurgence of anarchism as a vibrant form of leftWing activism in the late tWentieth century. In addressing the ideological basis and contested cultural meanings of armed struggle, it uncovers Why and how the Vancouver Five transformed themselves into an underground, clandestine force. -

Merchants of Death” Survive and Prosper

February, 2018 Vol. 47 No. 1 Jewish Peace Letter Published by the Jewish Peace Fellowship CONTENTS F-35A Lightning II Lawrence Witner Merchants Pg. 5 of Death Susannah Sexual Heschel Assaults Pg.3 & Harass- ments & American Jews Some Sug- gestions for Liberal Zion- ists and for Progressive Jews Who Are Not Patrick Henry What Ken Burns and Pg. 3 Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War Completely Missed: The Interfaith Anti- war Movement Hush, Hush, Murray Polner When One Person Pg. 6 Can Decide If We Live or Die. 2 • February, 2018 jewishpeacefellowship.org Questions we must ask Susannah “What is a religious Heschel person? A person who is maladjusted; attuned to the agony of others; aware of God’s presence and of God’s needs; a religious person is never satisfied, but always questioning, striving for something deeper, and always refusing to accept inequalities, the status quo, the cruelty and suffering of others.” Sexual Assaults & Harassments & American Jews hock and horror over individual cases of serial sexual harassers and assault- ers is just beginning and should not be a tool for ignoring the bigger problem that sexual harassment is used to prevent women from attaining their professional goals. S Yes, a few rabbis have spoken about the is- sue from the pulpit—and I admire them enor- mously—but this is an issue that should be addressed more widely within the Jewish community. So let us ask why so few women hold positions of leadership in Jew- Let us ask why ish communal organizations. Let us ask why I am still invited so few women to speak at conferences where I am hold positions the only woman on the program.