Valuing On-The-Ball Actions in Soccer: a Critical Comparison of Xt and VAEP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ilzers Apollon Mission!

Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. 32 | 6. August 2019 FOTOS: GEPA PICTURES 50 Wien 15 SEITEN PREMIER LEAGUE Manchester City will den Hattrick! ab Seite 21 AUSTRIA WIEN: VÖLLIG PUNKTELOS IN DEN EUROPACUP MARCEL KOLLER VS. LASK Aufwind nach dem Machtkampf Seite 6 Ilzers Apollon TOTO RUNDE 32A+32B Garantie 13er mit 100.000 Euro! Mission! Seite 8 Österreichische Post AG WZ 02Z030837 W – Sportzeitung Verlags-GmbH, Linke Wienzeile 40/2/22, 1060 Wien Retouren an PF 100, 13 Die Premier League live & exklusiv Der Auftakt mit Jürgen Klopps Liverpool vs. Norwich Ab Freitag 20 Uhr live bei Sky PR_AZ_Coverbalken_Sportzeitung_168x31_2018_V02.indd 1 05.08.19 10:52 Gratis: Exklusiv und Montag: © Shutterstock gratis nur für Abonnenten! EPAPER AB SOFORT IST MONTAG Dienstag: DIENSTAG! ZEITUNG DIE SPORTZEITUNG SCHON MONTAGS ALS EPAPER ONLINE LESEN. AM DIENSTAG IM POSTKASTEN. NEU: ePaper Exklusiv und gratis nur für Abonnenten! ARCHIV Jetzt Vorteilsabo bestellen! ARCHIV aller bisherigen Holen Sie sich das 1-Jahres-Abo Print und ePaper zum Preis von € 74,90 (EU-Ausland € 129,90) Ausgaben (ab 1/2018) zum und Sie können kostenlos 52 x TOTO tippen. Lesen und zum kostenlosen [email protected] | +43 2732 82000 Download als PDF. 1 Jahr SPORTZEITUNG Print und ePaper zum Preis von € 74,90. Das Abonnement kann bis zu sechs Wochen vor Ablauf der Bezugsfrist schriftlich gekündigt werden, ansonsten verlängert sich das Abo um ein weiteres Jahr zum jeweiligen Tarif. Preise inklusive Umsatzsteuer und Versand. Zusendung des Zusatzartikels etwa zwei Wochen nach Zahlungseingang bzw. ab Verfügbarkeit. Solange der Vorrat reicht. Shutterstock epaper.sportzeitung.at Montag: EPAPER Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. -

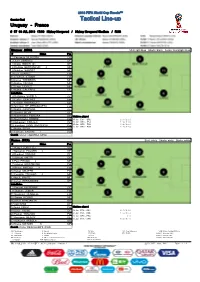

Tactical Line-Up Uruguay - France # 57 06 JUL 2018 17:00 Nizhny Novgorod / Nizhny Novgorod Stadium / RUS

2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ Quarter-final Tactical Line-up Uruguay - France # 57 06 JUL 2018 17:00 Nizhny Novgorod / Nizhny Novgorod Stadium / RUS Uruguay (URU) Shirt: light blue Shorts: black Socks: black/light blue # Name Pos 1 Fernando MUSLERA GK 2 Jose GIMENEZ DF 3 Diego GODIN (C) DF 6 Rodrigo BENTANCUR X MF 8 Nahitan NANDEZ MF 9 Luis SUAREZ FW 11 Cristhian STUANI FW 14 Lucas TORREIRA MF 15 Matias VECINO MF 17 Diego LAXALT MF 22 Martin CACERES DF Substitutes 4 Guillermo VARELA DF 5 Carlos SANCHEZ MF 7 Cristian RODRIGUEZ MF 10 Giorgian DE ARRASCAETA FW 12 Martin CAMPANA GK 13 Gaston SILVA DF 16 Maximiliano PEREIRA DF Matches played 18 Maximiliano GOMEZ FW 15 Jun EGY - URU 0 : 1 ( 0 : 0 ) 19 Sebastian COATES DF 20 Jun URU - KSA 1 : 0 ( 1 : 0 ) 25 Jun URU - RUS 3 : 0 ( 2 : 0 ) 20 Jonathan URRETAVISCAYA FW 30 Jun URU - POR 2 : 1 ( 1 : 0 ) 23 Martin SILVA GK 21 Edinson CAVANI I FW Coach Oscar TABAREZ (URU) France (FRA) Shirt: white Shorts: white Socks: white # Name Pos 1 Hugo LLORIS (C) GK 2 Benjamin PAVARD X DF 4 Raphael VARANE DF 5 Samuel UMTITI DF 6 Paul POGBA X MF 7 Antoine GRIEZMANN FW 9 Olivier GIROUD X FW 10 Kylian MBAPPE FW 12 Corentin TOLISSO X MF 13 Ngolo KANTE MF 21 Lucas HERNANDEZ DF Substitutes 3 Presnel KIMPEMBE DF 8 Thomas LEMAR FW 11 Ousmane DEMBELE FW 15 Steven NZONZI MF 16 Steve MANDANDA GK 17 Adil RAMI DF 18 Nabil FEKIR FW Matches played 19 Djibril SIDIBE DF 16 Jun FRA - AUS 2 : 1 ( 0 : 0 ) 20 Florian THAUVIN FW 21 Jun FRA - PER 1 : 0 ( 1 : 0 ) 26 Jun DEN - FRA 0 : 0 22 Benjamin MENDY DF 30 Jun FRA - ARG 4 : 3 ( 1 : 1 ) 23 Alphonse AREOLA GK 14 Blaise MATUIDI N MF Coach Didier DESCHAMPS (FRA) GK: Goalkeeper A: Absent W: Win GD: Goal difference VAR: Video Assistant Referee DF: Defender N: Not eligible to play D: Drawn Pts: Points AVAR 1: Assistant VAR MF: Midfielder I: Injured L: Lost AVAR 2: Offside VAR FW: Forward X: Misses next match if booked GF: Goals for AVAR 3: Support VAR C: Captain MP: Matches played GA: Goals against FRI 06 JUL 2018 15:08 CET / 16:08 Local time - Version 1 22°C / 71°F Hum.: 53% Page 1 / 1. -

Media Value in Football Season 2014/15

MERIT report on Media Value in Football Season 2014/15 Summary - Main results Authors: Pedro García del Barrio Director Académico de MERIT social value Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona) Bruno Montoro Ferreiro Analista de MERIT social value Asier López de Foronda López Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona) With the collaboration of: Josep Maria Espina Serra (UIC Barcelona) Arnau Raventós Gascón (UIC Barcelona) Ignacio Fernández Ponsin (UIC Barcelona) www.meritsocialvalue.com 2 Presentation MERIT (Methodology for the Evaluation and Rating of Intangible Talent) is part of an academic project with vast applications in the field of business and company management. This methodology has proved to be useful in measuring the economic value of intangible talent in professional sport and in other entertainment industries. In our estimations – and in the elaboration of the rankings – two elements are taken into consideration: popularity (degree of interest aroused between the fans and the general public) and media value (the level of attention that the mass media pays). The calculations may be made at specific points in time during a season, or accumulating the news generated during a particular period: weeks, months, years, etc. Additionally, the homogeneity amongst the measurements allows for a comparison of the media value status of individuals, teams, institutions, etc. Together with the measurements and rankings, our database allows us to conduct analyses on a wide variety of economic and business problems: estimates of the market value (or “fair value”) of players’ transfer fees; calculation of the brand value of individuals, teams and leagues; valuation of the economic return from alliances between sponsors; image rights contracts of athletes and teams; and a great deal more. -

2019-20 Impeccable Premier League Soccer Checklist Hobby

2019-20 Impeccable Premier League Soccer Checklist Hobby Autographs=Yellow; Green=Silver/Gold Bars; Relic=Orange; White=Base/Metal Inserts Player Set Card # Team Print Run Callum Wilson Gold Bar - Premier League Logo 13 AFC Bournemouth 3 Harry Wilson Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 8 AFC Bournemouth 25 Joshua King Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 7 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lewis Cook Auto - Jersey Number 2 AFC Bournemouth 16 Lewis Cook Auto - Rookie Metal Signatures 9 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lewis Cook Auto - Stats 14 AFC Bournemouth 4 Lewis Cook Auto Relic - Extravagance Patch + Parallels 5 AFC Bournemouth 140 Lewis Cook Relic - Dual Materials + Parallels 10 AFC Bournemouth 130 Lewis Cook Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 6 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Jersey Number 14 AFC Bournemouth 26 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Rookie + Parallels 1 AFC Bournemouth 140 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Rookie Metal Signatures 1 AFC Bournemouth 25 Ryan Fraser Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 5 AFC Bournemouth 25 Aaron Ramsdale Metal - Rookie Metal 1 AFC Bournemouth 50 Callum Wilson Base + Parallels 9 AFC Bournemouth 130 Callum Wilson Metal - Stainless Stars 2 AFC Bournemouth 50 Diego Rico Base + Parallels 5 AFC Bournemouth 130 Harry Wilson Base + Parallels 7 AFC Bournemouth 130 Jefferson Lerma Base + Parallels 1 AFC Bournemouth 130 Joshua King Base + Parallels 2 AFC Bournemouth 130 Nathan Ake Base + Parallels 3 AFC Bournemouth 130 Nathan Ake Metal - Stainless Stars 1 AFC Bournemouth 50 Philip Billing Base + Parallels 8 AFC Bournemouth 130 Ryan Fraser Base + Parallels 4 AFC -

Uefa Euro 2012 Match Press Kit

UEFA EURO 2012 MATCH PRESS KIT Netherlands Denmark Group B - Matchday 1 Metalist Stadium, Kharkiv Saturday 9 June 2012 18.00CET (19.00 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Match facts........................................................................................................................5 Team facts.........................................................................................................................7 Squad list...........................................................................................................................9 Head coach.....................................................................................................................11 Match officials..................................................................................................................12 Competition facts.............................................................................................................13 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................15 UEFA information............................................................................................................16 Legend............................................................................................................................17 -

Identifying Diversity of Thought on Social Media

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2019 Identifying Diversity of Thought on Social Media Beth Bullemer Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Repository Citation Bullemer, Beth, "Identifying Diversity of Thought on Social Media" (2019). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 2154. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/2154 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTIFYING DIVERSITY OF THOUGHT ON SOCIAL MEDIA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by BETH BULLEMER B.F.A., Carnegie Mellon University, 2004 M.S., Wright State University, 2015 2019 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL April 23, 2019 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE DISSERTATION PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Beth Bullemer ENTITLED Identifying Diversity of Thought on Social Media BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. Valerie L. Shalin, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Scott N. J. Watamaniuk, Ph.D. Graduate Program Director Debra Steele-Johnson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Psychology Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination: Gary Burns, Ph.D. Joe Houpt, Ph.D. Valerie L. Shalin, Ph.D. Amit Sheth, Ph.D. -

2015 Topps Premier Gold Soccer Checklist

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Artur Boruc AFC Bournemouth 2 Tommy Elphick AFC Bournemouth 3 Marc Pugh AFC Bournemouth 4 Harry Arter AFC Bournemouth 5 Matt Ritchie AFC Bournemouth 6 Max Gradel AFC Bournemouth 7 Callum Wilson AFC Bournemouth 8 Theo Walcott Arsenal 9 Laurent Koscielny Arsenal 10 Mikel Arteta Arsenal 11 Aaron Ramsey Arsenal 12 Santi Cazorla Arsenal 13 Mesut Ozil Arsenal 14 Alexis Sanchez Arsenal 15 Olivier Giroud Arsenal 16 Bradley Guzan Aston Villa 17 Jordan Amavi Aston Villa 18 Micah Richards Aston Villa 19 Idrissa Gueye Aston Villa 20 Jack Grealish Aston Villa 21 Gabriel Agbonlahor Aston Villa 22 Rudy Gestede Aston Villa 23 Thibaut Courtois Chelsea 24 Branislav Ivanovic Chelsea 25 John Terry Chelsea 26 Nemanja Matic Chelsea 27 Eden Hazard Chelsea 28 Cesc Fabregas Chelsea 29 Radamel Falcao Chelsea 30 Diego Costa Chelsea 31 Julian Speroni Crystal Palace 32 Scott Dann Crystal Palace 33 Joel Ward Crystal Palace 34 Jason Puncheon Crystal Palace 35 Yannick Bolasie Crystal Palace 36 Mile Jedinak Crystal Palace 37 Wilfried Zaha Crystal Palace 38 Connor Wickham Crystal Palace 39 Tim Howard Everton 40 Leighton Baines Everton 41 Seamus Coleman Everton 42 Phil Jagielka Everton 43 Ross Barkley Everton 44 John Stones Everton 45 Romelu Lukaku Everton 46 Kasper Schmeichel Leicester City 47 Wes Morgan Leicester City 48 Robert Huth Leicester City 49 Riyad Mahrez Leicester City 50 Jeff Schlupp Leicester City 51 Shinji Okazaki Leicester City 52 Jamie Vardy Leicester City 53 Simon Mignolet Liverpool FC 54 Martin Skrtel Liverpool FC 55 Nathaniel Clyne Liverpool -

Page 21 March 17.Indd

SPORT Friday 17 Marchrch 20172017 PAGE | 21 PAGE | 222 PAGE | 23 Kyrgios stuns Djokovicokovic Smith, Maxwell drivee Guardiola faces again as Federer Australia in test of resolve races past Nadal Ranchi Test after City's exit GCC ROAD CYCLING CHAMPIONSHIPS: RESULTS OF DAY THREE CADETS CLASS, 46KMS UAE riders seal top three Abdurrahman Al Sultan, Saudi Arabia, 1:18.14 Jassim Mohammed Hussain, Bahrain, same time Ali Nasir Ahmed, Bahrain, same time Abdullah Ibrahim Hassan, Bahrain, same time Rashid Al Mansoori, UAE, same time JUNIORS CLASS, 80.5 KMS spots in Junior Road Race Hamad Abdullah Al Mahri, UAE, 2:07.09 Rashid Abdullah Suwaidaan, UAE, 2:07.12 Rizwan Rehmat Abdullah Abdulkareem, UAE, same time The Peninsula Mohammed Ibrahim Abdullah, Bahrain, 2:10.50 Farhan Alfaraizi, Qatar, same time iders from the United OVERALL TIMES: Arab Emirates (UAE), UAE, 6:21.33 a cycling powerhouse Saudi Arabia, 6:46.03 in the region, clinched Bahrain, 6:50.37 the top three spots in Rthe Junior Class on the penulti- mate day of the GCC Road Race Championships. UAE's Hamad Abdullah Al Mahri clocked a time of 2:07.09 to grab the first spot in the 80.5kms race. He was followed to the finish line by compatriot Rashid Abdullah Suwaidaan (2:07.12). In the third place was Abdul- lah Abdulkareem, also representing the UAE. Bahrain's Mohammed Ibra- him Abdullah (2:10.50) and GCC Road Cycling Championships UAE riders clinch top three spots in the Riders compete on day three of the GCC Road Cycling Championships near the Losail international Circuit Junior Class. -

Tuesday, July 14, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI TUESDAY, JULY 14, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 ■ MULLER CITES HEALTH REASONS SHOCK RESIGNATION ■ NATIONAL PARTY IN TURMOIL AS MPS DISCUSS WHERE TO FROM HERE AFTER JUST 53 DAYS PAGES 6, 7 $40M FOR POOL UPGRADE OLYMPIC POOL COMPLEX Shovel-ready project adds to ‘great things to do in Gisborne’ — PM A $45 MILLION boost to upgrade Gisborne’s “These shovel-ready projects, funded by the access between changing rooms to pool). were “just shy” of $35m. Olympic Pool Complex and Midway Surf infrastructure fund within the Covid Response Midway Surf Lifesaving Club will benefit GDC previously said the increase in cost Lifesaving Club premises will create jobs and and Recovery Fund, will not only add to the from construction of a purpose-built hub was down to a change in design processes. improve facilities for both locals and visitors, great things to do in Gisborne, they will help that will offer sites for two new hospitality Overall, the Government will provide $106m Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said today. place and keep people in jobs, and inject businesses, giving the club ongoing income on infrastructure and community facilities in “We know the economic recovery from the money into the area,” Ms Ardern said. and increasing the club’s appeal. the region to boost its post-Covid recovery. global Covid-19 pandemic is especially hard “This investment reflects the Government’s All approvals are in principle and subject to The first of these was announced earlier this on our regions, which is why the Government Covid economic recovery plan which is about contract negotiations. -

Big-5 Weekly Post

CIES Football Observatory Issue n°120 - 28/09/2015 Big-5 Weekly Post Best players since the start of the season Premier League Liga Position All players U21 Position All players U21 Laurent Koscielny Chancel Mbemba Iñigo Martínez Carlos Vigaray CB CB Arsenal FC Newcastle United FC Real Sociedad de Fútbol Getafe CF Cédric Soares Jordan Amavi Marcelo Vieira João Cancelo FB FB Southampton FC Aston Villa FC Real Madrid CF Valencia CF Santi Cazorla Emre Can Luka Modrić Víctor Camarasa DM DM Arsenal FC Liverpool FC Real Madrid CF Levante UD Mesut Özil Nathan Redmond Fabián Orellana Alen Halilović AM AM Arsenal FC Norwich FC RC Celta de Vigo Real Sporting de Gijón Riyad Mahrez Raheem Sterling Lionel Messi Isaac Success FW FW Leicester City FC Manchester City FC FC Barcelona Granada CF Ligue 1 Bundesliga Position All players U21 Position All players U21 Thiago Silva Olivier Boscagli Jérôme Boateng Jonathan Tah CB CB Paris St-Germain FC OGC Nice FC Bayern München Bayer 04 Leverkusen Serge Aurier Benjamin Mendy Wendell Nascimento Ulisses Garcia FB FB Paris St-Germain FC Olympique de Marseille Bayer 04 Leverkusen SV Werder Bremen Lassana Diarra Vincent Koziello Ilkay Gündoğan Julian Weigl DM DM Olympique de Marseille OGC Nice BV 09 Borussia Dortmund BV 09 Borussia Dortmund Wahbi Khazri Bernardo Silva Douglas Costa Hakan Çalhanoğlu AM AM FC Girondins de Bordeaux AS Monaco FC Bayern München Bayer 04 Leverkusen Michy Batshuayi Corentin Jean Robert Lewandowski Michael Gregoritsch FW FW Olympique de Marseille ES Troyes Aube Champagne FC Bayern München -

Download Panini Colourable Football Stickers

2 1 1.89M 82KG GER BERND LENO D.O.B. 04-03-92 | Bietighem-Bissingen 7 10 1.80M 71KG GER MESUT ÖZIL D.O.B. 15-10-88 | Gelsenkirchen 3 14 1.87M 80KG GAB PIERRE-EMERICK AUBAMEYANG D.O.B. 18-06-89 | Laval (France) 10 1 1.88M 85KG ENG HG TOM HEATON D.O.B. 15-04-86 | Chester 5 40 1.96M 77KG ENG HG TYRONE MINGS D.O.B. 13-03-93 | Bath 1 7 1.78M 68KG SCO JOHN McGINN D.O.B. 18-10-94 | Glasgow 8 5 1.80M 75KG NED HG NATHAN AKÉ D.O.B. 18-02-95 | Den Haag 4 24 1.63M 70KG SCO RYAN FRASER D.O.B. 24-02-94 | Aberdeen 5 13 1.80M 66KG ENG HG CALLUM WILSON D.O.B. 27-02-92 | Coventry 3 1 1.84M 82KG AUS MAT RYAN D.O.B. 08-04-92 | Plumpton 3 13 1.81M 71KG GER PASCAL GROß D.O.B. 15-06-91 | Mannheim 4 18 1.74M 68KG AUS HG AARON MOOY D.O.B. 15-09-90 | Sydney 4 1 1.91M 76KG ENG HG NICK POPE D.O.B. 19-04-92 | Soham 4 5 1.85M 81KG ENG HG JAMES TARKOWSKI D.O.B. 19-11-92 | Manchester 4 7 1.86M 78KG ICL JÓHANN GUDMUNDSSON D.O.B. 27-10-90 | Reykjavik 2 1 1.86M 88KG ESP KEPA ARRIZABALAGA D.O.B. 03-10-94 | Ondarroa 1 19 1.78M 70KG ENG MASON MOUNT D.O.B. -

Match Report Croatia - Denmark 1 : 1 AET (1 : 1, 1 : 1) 3 : 2 PSO # 52 01 JUL 2018 21:00 Nizhny Novgorod / Nizhny Novgorod Stadium / RUS Att: 40,851

2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ Round of 16 Match report Croatia - Denmark 1 : 1 AET (1 : 1, 1 : 1) 3 : 2 PSO # 52 01 JUL 2018 21:00 Nizhny Novgorod / Nizhny Novgorod Stadium / RUS Att: 40,851 Croatia (CRO) Denmark (DEN) Coach Zlatko DALIC (CRO) Coach Age HAREIDE (NOR) Att : Attendance VAR : Video Assistant Referee VAR 1 : Assistant VAR VAR 2 : Offside VAR AVAR 3 : Support VAR (C) : Captain A : Absent PSO : Penalty shoot-out Y : Single yellow card AET : After extra time I : Injured HT : Half-time R : Direct red card ETHT : Extra time half time N : Not eligible to play FT : Full-time 2Y : Expulsions due to Second Caution SUN 01 JUL 2018 22:48 CET / 23:48 Local time - Version 1 Page 1 / 2 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ Round of 16 Match statistics Croatia - Denmark 1 : 1 AET (1 : 1, 1 : 1) 3 : 2 PSO # 52 01 JUL 2018 21:00 Nizhny Novgorod / Nizhny Novgorod Stadium / RUS Att: 40,851 Croatia (CRO) Statistics * Denmark (DEN) BUD Man of the Match: 1, Kasper SCHMEICHEL (Denmark) Fouls Fouls # Name Pos Min GF GA AS S/SG PK Y 2Y R # Name Pos Min GF GA AS S/SG PK Y 2Y R FC FS FC FS 23 SUBASIC GK 120 1 1 SCHMEICHEL GK 120 1 2 VRSALJKO DF 120 1/0 2 4 KJAER DF 120 1 3 STRINIC DF 81 1 1 5 KNUDSEN DF 120 1 4 PERISIC FW 97 6/0 1 6 CHRISTENSEN DF 45 1 6 LOVREN DF 120 1/0 1 8 DELANEY MF 98 1 1/0 4 1 7 RAKITIC MF 120 4/3 1 3 10 ERIKSEN MF 120 4/0 10 MODRIC MF 120 3/2 0/1 1 2 11 BRAITHWAITE FW 105 3/1 2 11 BROZOVIC MF 71 1 13 M.