Wilson Harris and the Experimental Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Fairbank

CHRISTOPHER FAIRBANK Film: Zygielbojm's Death Adam Ryszard Brylski Wytwornia Filmow The Show Patsy Bleaker Mitch Jenkins The Show The Fight Frank Jessica Hynes Unstoppable Entertainment Walk Like a Panther Lesley Beck Dan Cadan Fox International Productions Viy 2: Journey to China: Grey Oleg Stepchenko C T B Film Company Papillon Jean Castili Michael Noer Bleeker Street Media Lady Macbeth Boris William Oldroyd Sixty Six Pictures Guardian of the Galaxy The Broker James Gunn Marvel Studios Hercules Gryza Brett Ratner MGM Orthodox Goldberg David Leon Zeitgeist Films Writers Retreat Nigel Diego Rocha MoliFilms Entertainment Boogeyman 4 Franklin / Skinner Jeffrey Lando UFO Films Jack the Giant Slayer Uncle Bryan Singer Red Lion Films Ltd Pirates of the Caribbean 4 Ezekiel Rob Marshall Walt Disney Little Deaths X Andrew Parkinson Almost Midnight Productions Mindflesh Verdain Robert Pratten Zen Films Flushed Away Thimblenose Ted/ Cockroach David Bowers, Sam Fell Aardman Animations Almost Heaven Teapot Ted Shell Pearcey Almost Heaven Productions Cargo Ralph Clive Gordon Slate Films Goal! Foghorn Danny Cannon Goal Productions Below Pappy David Twohy Dimension Films The Bunker Sgt. Heydrich Rob Green Millenium Pictures The Fifth Element Prof. Mactilburgh Luc Bresson Zaltman Films Aliens I I I Murphy David Fincher C20 Fox Hamlet Player Queen Franco Zefferelli Marquis Films White Hunter Black Heart Tom Harrison Clint Eastwood Warner Bros Batman Nick Derelict Tim Burton Warner Bros Venus Peter Blindman Ian Sellar British Film Institute Hanna's War -

A Study of the Motion Picture Relief Fund's Screen Guild Radio Program 1939-1952. Carol Isaacs Pratt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 A Study of the Motion Picture Relief Fund's Screen Guild Radio Program 1939-1952. Carol Isaacs Pratt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pratt, Carol Isaacs, "A Study of the Motion Picture Relief Fund's Screen Guild Radio Program 1939-1952." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Christopher Fairbank

VAT No. 993 055 789 CHRISTOPHER FAIRBANK FILM : Journey to China: Grey Aldamisa Entertainment Oleg Stepchenko The Mystery of Iron Mask Lady Macbeth Boris Sixty Six Pictures William Oldroyd London Fields Grizzle Nicola Six Ltd Matthew Cullen Guardian of the Galaxy The Broker Marvel Studios James Gunn Hercules Gryza MGM Brett Ratner Orthodox Goldberg Zeitgeist Films David Leon Boogeyman 4 Franklin / Skinner UFO Films Jeffrey Lando Jack the Giant Slayer Uncle Red Lion Films Ltd Bryan Singer Pirates of the Caribbean 4 Ezekiel Walt Disney Rob Marshall Almost Heaven Teapot Ted Almost Heaven Pro Shell Pearcey Cargo Ralph Slate Films Clive Gordon Goal Foghorn Goal Productions Danny Cannon The Bunker Heydrich Millenium Pictures Rob Green The Fifth Element Prof. Mactilburgh Zaltman Films Luc Bresson Aliens Iii Murphy C20 Fox David Fincher Hamlet Player Queen Marquis Films Franco Zefferelli White Hunter Black Heart Tom Harrison Warner Bros Clint Eastwood Batman Nick Derelict Warner Bros Tim Burton Venus Peter Blindman British Film Institute Ian Sellar Hanna's War Reuven Cannon Menachem Golan Plenty Spencer Pressman Films Fred Schepsi Agatha Lulund Warner Bros Michael Apted The Awakening Jack Bendigo Film Co Mike Newell Cry Wolf Sergeant Picture P'ship Lezek Burzgnski Little Lord Fauntleroy Rosemont Productions Jack Gold TELEVISION: Taboo Ibbotsen Hardy, Son and Barker Tim Bricknell The Secret Agent Yundt BBC Charles McDougall Dickensian Silas Wegg Red Planet (Dickens) Ltd Harry Bradbeer Wolf Hall Walter Cromwell BBC / Company Pictures Peter Kosminsky -

Dvds at MCL As of JAN 2016

ALL DVDs at MCL as of JAN 2016 (Alphabetical) Title Category DEWEY 1 2 3 MAGIC: MANAGING DIFFICULT BEHAVIOR IN CHILDREN 2-12 (DVD) Psychological Issues 649.64 ONE 10 ITEMS OR LESS (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 10 MINUTE SOLUTION: HOT BODY BOOT CAMP (DVD) Health & Fitness 613.71 TEN 10 MINUTE SOLUTIONS: QUICK TUMMY TONERS (DVD) Health & Fitness 613.71 TEN 10 THINGS I HATE ABOUT YOU (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 100 CARTOON CLASSICS (DVD) Children's Programs 100 YEARS OF THE WORLD SERIES (DVD) Recreation & Sports 796.357 ONE 100, THE: SEASON 1 (DVD) Television 100, THE: SEASON 2 (DVD) Television 1000 TIMES GOOD NIGHT (DVD) Movies - Foreign - Norway 1001 CLASSIC COMMERCIALS (DVD) Documentary, History & Biography 659.143 ONE 101 DALMATIANS (DVD) (Animated) Children's Programs 101 DALMATIANS (DVD) (Diamond Edition) Children's Programs 101 DALMATIANS II: PATCH'S LONDON ADVENTURE (DVD) Children's Programs 101 FITNESS GAMES FOR KIDS AT CAMP VOL 5: STRENTH AND AGILITY GAMES (DVD) Children's Information 613.7042 ONE 101 REYKJAVIK (DVD) (Icelandic) Movies - Foreign - Iceland 102 DALMATIANS (DVD) Children's Programs 11 FLOWERS (DVD) (Chinese) Movies - Foreign - China 11TH OF SEPTEMBER: MOYERS IN CONVERSATION (DVD) Documentary, History & Biography 12 (DVD) (Russian) Movies - Foreign - Russia 12 ANGRY MEN (DVD) Movies - Classic 12 MONKEYS (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 12 YEARS A SLAVE (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 12:01 (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 127 HOURS (DVD) Movies - Contemporary 13 ASSASSINS (DVD)(Japan) Movies - Foreign - Japan 13 GHOSTS (DVD) Movies -

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2009

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2009 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Wangenheim Collection Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABDULLAH Abdullah, Shaila, 1971- Saffron dreams : a novel FIC/ADAMS Adams, Will, 1963- The Alexander cipher FIC/ADLER Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) There's something about St. Tropez FIC/AKPAN Akpan, Uwem. Say you're one of them FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- For one more day FIC/ALCORN Alcorn, Randy C. Safely home FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Hannah. A killing frost FIC/ALLEN Allen, Sarah Addison. Garden spells FIC/ALLEN Allen, Sarah Addison. The sugar queen FIC/ALLENDE Allende, Isabel. The infinite plan : a novel FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. The green man FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Kevin J., 1962- Enemies & allies FIC/ANDREWS Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- Hissy fit FIC/APPELFELD Appelfeld, Aron. Laish FIC/ARELLANO Arellano, Robert. Havana lunar [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity and the next of kin FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. Behind the scenes at the museum FIC/ATWOOD Atwood, Margaret, 1939- The year of the flood : a novel FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. The mammoth hunters FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. The plains of passage FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Sense and sensibility FIC/BADEN Baden, Michael M. Skeleton justice : a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- Murder on parade : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel [SCI-FI] FIC/BAKKER Bakker, R. -

Bedfordshire, to See the Aircraft Used in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines

Lights, Camera Action! Discover the scenes and locations of your favourite films and television programmes in the East of England. z In Hertfordshire, pay a visit to Borehamwood – Britain’s very own ‘Hollywood’, which during the 1980’s could boast six out of the top ten box office hits of all time. z Explore the timber-framed villages of Essex, home to the loveable antiques rogue ‘Lovejoy’. z Take a wander in the footsteps of Captain Mainwaring and his Dad’s Army in Norfolk. z Go spy-busting with special agent 007 James Bond in Cambridgeshire. z For those looking for classic inspiration, head to the homes and gardens featured in Bleak House, Vanity Fair, Lady Audley’s Secret and David Copperfield. z Take to the skies in Bedfordshire, to see the aircraft used in Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines. z Follow the clues to the crime scenes of P. D. James and Ruth Rendell – and their television adaptations set in Suffolk. This information sheet brings together a selection of films and television programmes which have been made in the East of England. We would like to thank Screen East for their help and assistance. Contents Film and Television Locations Bedfordshire 2 Cambridgeshire 4 Essex 7 Hertfordshire 11 Norfolk 22 Suffolk 28 www.visiteastofengland.com 1 Produced by East of England Tourism BEDFORDSHIRE Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) Musical, Fantasy Director: Ken Hughes. Starring: Dick van Dyke, Sally Ann Howes and Lionel Jefferies. Film Fantasy children’s musical. Inventor Caractacus Potts buys an old racing car, and transforms it into ‘Chitty Chitty Bang 28 Days Later… (2002) Horror, Thriller Bang’ - which can magically fly and float on water. -

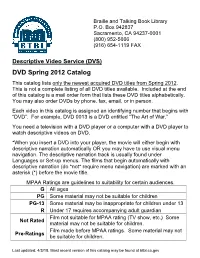

DVD Spring 2012 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2012

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2012 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2012. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0013 is a DVD entitled “The Art of War.” You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. *When you insert a DVD into your player, the movie will either begin with descriptive narration automatically OR you may have to use visual menu navigation. The descriptive narration track is usually found under Languages or Set-up menus. The films that begin automatically with descriptive narration (do *not* require menu navigation) are marked with an asterisk (*) before the movie title. MPAA Ratings are guidelines to suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not Pre-Ratings be suitable for children. -

Even After 50 Years, Comedy Writing Is A

Source: Daily Express {Main} Edition: Country: UK Date: Thursday 17, September 2020 Page: 24,25 Area: 1289 sq. cm Circulation: ABC 251736 Daily Ad data: page rate £20,825.00, scc rate £128.00 Phone: 020 7928 8000 Keyword: W&N T’S BEEN close to 100 degrees Rob Crossan in parts of California over the By Even after past few weeks. But for two Britons, who have spent the best on and having to say, ‘Wait a minute, part of half-a-century living where’s the diversity in this script?’” deep in the Hollywood Hills, it’s One wonders if classics such as The 50 years, aI temperature change of a different Likely Lads would even be commis- kind that’s been making them hot sioned these days. One thing is cer- under the collar. tain, says Ian: “We can’t just write “I just couldn’t believe it. It did white, male parts and that’s a good comedy drive me a bit crazy when I heard,” thing. But I think it looks just as bad says Dick Clement, who with his to specify a character as ‘Asian’, or writing partner Ian La Frenais, ‘Afro-American’ in a script as it created some of the most beloved TV looks forced.” writing is shows and films of the past 50 years The pair were asked to remove a including The Likely Lads, Porridge passage of dialogue in their Porridge and Auf Wiedersehen, Pet. reboot, starring Kevin Bishop, that He is referring, of course, to involved the mention of slavery. -

Features: Debut Fiction Body/Mind/Spirit Travel Spotlight: Lgbtq+ + May/June 2021

125+ NEW INDIE BOOKS REVIEWED INSIDE ® FEATURES: DEBUT FICTION BODY/MIND/SPIRIT TRAVEL SPOTLIGHT: LGBTQ+ + MAY/JUNE 2021 Celebrating Five Years in Children’s Book Publishing Fifteen Years in Performing Arts Education and Theatrical Productions for Children 2021 TITLES Frontlist & Featured FREE TEACHER GUIDES AUDIO-VIDEO BOOKS Curriculums and Worksheets for the visually and hearing impaired anchored by SEL Standards, produced in partnership with US / State Core Curriculum and Imagination Videobooks and a grant from Social Justice Standards NOTABLE TITLES the US Department of Education Foreword INDIES – 5 Finalists + Silver & Bronze Moonbeam - Gold - Best Picture Book Series Purple Dragonfly–Silver • Royal Dragonfly–Gold Critically Acclaimed and Featured by Kirkus Reviews Foreword Reviews - Starred + Clarion 5 Stars EDUCATIONAL & PERFORMANCE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CONTENT LICENSING RIGHTS LICENSING Original Theatrical Production Materials Sylvia Hayse Literary Agency for Elementary and Middle School (Q1-22) [email protected] AUTHOR VISITS & RESOURCES [email protected] / 303.840.5787 http://www.notablekidspublishing.com Distributed Exclusively by Independent Publishers Group http://www.ipgbook.com FOREWORD AD.indd 3 4/12/21 12:34 PM Become more balanced, con dent, & joyful in your professional life ISBN: 9781951075651 | Publication date: February 22, 2021 “Shout this from the mountaintop: “SOUL! is a must-read If you touch the life of for school and district staff.” a child as a teacher, —Daniel Cohan, chief of secondary paraprofessional, schools, Jeffco Public Schools, Colorado coach, principal, or counselor, you must read this book!” —Thomasenia Lott Adams, associate dean for research and “This amazing book touches faculty development, College of the core of our being Education, University of Florida and helps us ful ll the promise of our professional lives.” —Denise M.