Settlements in Cape Town, 1939-1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

2011 Census - Cape Flats Planning District August 2013

City of Cape Town – 2011 Census - Cape Flats Planning District August 2013 Compiled by Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS), City of Cape Town 2011 Census data supplied by Statistics South Africa (Based on information available at the time of compilation as released by Statistics South Africa) Overview, Demographic Profile, Economic Profile, Dwelling Profile, Household Services Profile Planning District Description The Cape Flats Planning District is located in the southern part of the City of Cape Town and covers approximately 13 200 ha. It is bounded by the M5 in the west, N2 freeway to the north, Lansdowne Road and Weltevreden Road in the east and the False Bay coastline to the south. 1 Data Notes: The following databases from Statistics South Africa (SSA) software were used to extract the data for the profiles: Demographic Profile – Descriptive and Education databases Economic Profile – Labour Force and Head of Household databases Dwelling Profile – Dwellings database Household Services Profile – Household Services database Planning District Overview - 2011 Census Change 2001 to 2011 Cape Flats Planning District 2001 2011 Number % Population 509 162 583 380 74 218 14.6% Households 119 483 146 243 26 760 22.4% Average Household Size 4.26 3.99 In 2011 the population of Cape Flats Planning District was 583 380 an increase of 15% since 2001, and the number of households was 146 243, an increase of 22% since 2001. The average household size has declined from 4.26 to 3.99 in the 10 years. A household is defined as a group of persons who live together, and provide themselves jointly with food or other essentials for living, or a single person who lives alone (Statistics South Africa). -

Thesis Hum 2005 Alexander A.Pdf

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Commercial Diplomacy, Cultural Encounter and Slave Resistance: Episodes from Three VOC Slave Trading Voyages from the Cape to ~adagascar,1760-1780 Andrew Alexander ALXAND003 A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Cape Town Town 2005 Cape of This work has not been previously submitted in whole. or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in. this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed. and has been cited and referenced.University Signature: ~ Date: Contents Acknowledgements II Abstract 111 Introduction L Negotiation, Trade and the Rituals of Encounter: Generalised Patterns and Concrete Examples 14 II. De Zon and De Neptunus: The Predicaments of Cultural Misunderstanding and Personal Conflict 64 III. The lVfeermin and De Zan: Understanding the Impulses that have Shaped Shipboard Slave Uprisings 119 Town Conclusion 162 References Cape 164 of University Acknowledgements I would like to thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) for their provision of financial assistance that has made the completion of this dissertation possible. Town Cape of University II Abstract The intention of this dissertation is to fill a gap in a rich and yet under-represented aspect ofIndian Ocean slave history. -

Measuring the Effects of Political Reservations Thinking About Measurement and Outcomes

J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Course Material University of Cape Town 23 – 27 January 2012 J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Table of Contents Programme ................................................................................................................................ 3 Maps and Directions .................................................................................................................. 5 Course Objectives....................................................................................................................... 7 J-PAL Lecturers ......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Participants .................................................................................................................... 11 Group Assignment .................................................................................................................. 12 Case Studies ............................................................................................................................. 13 Case Study 2: Learn to Read Evaluations ............................................................................... 18 Case Study 3: Extra Teacher Program .................................................................................... 27 Case Study 4: Deworming in Kenya ....................................................................................... 31 Exercises -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

What Is a General Valuation Roll?

General Valuation 2018 (GV2018) What is a General Valuation Roll? A General Valuation Roll is a document containing the municipal valuations of about 875 000 registered properties within the boundaries of Cape Town. All properties on the GV Roll are valued at market value as of the date of valuation. Every municipality is legally required to produce a General Valuation Roll at least once every four years but the City of Cape Town produces theirs every three years, to help mitigate big fluctuations in property values. General Valuation Roll for 2018 (GV2018)? The GV2018 Roll is scheduled to be certified by the municipal valuer on 31 January 2019 and will be implemented together with the approved budget on 1 July 2019. The valuation of all properties on the GV2018 Roll is determined according to market conditions on the date of valuation as at 2 July 2018. The rate-in-the-rand to be taxed against property values, will be determined by Council in March 2019, together with the tabling of the budget. This will enable us to fund municipal services as outlined in the Integrated Development Plan. Please note: property valuations are determined objectively and according to market values. They are an indication in the growth of the value of the property and while the valuation is used to determine the rates income for the City, it is not an arbitrarily increased value. Valuations are done based on international standards and prescribed methodology, and the City processes are audited by a qualified external auditor to ensure compliance. Review of the GV2018 Roll Property owners can expect their GV2018 notices during February 2019, followed by the opportunity to submit any objections to the market value of their property or information on the GV2018 Roll. -

The Ultimate Digital Nomad Guide

THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL NOMAD GUIDE CAPE TOWN 2020 CAPE TOWN - NEW DIGITAL NOMAD HOTSPOT Cape Town has become an attractive destination for digital nomads, looking to venture to an African city and explore the local cultures and diverse wildlife. Cape Town has also become known as Africa’s largest tech hub and is bustling with young startups and small businesses. Cape Town is definitely South Africa’s trendiest city with hipster bars and restaurants along Bree street, exclusive beach strips with five star cuisine and rolling vineyards and wine farms. But is Cape Town a good city for digital nomads. We will dive into this and look at accommodation, co-working spaces, internet connectivity,safety and more. Let's jump into a guide to living and working as a digital nomad in Cape Town, written by digital nomads, from Cape Town. VISA There are 48 countries that do not need a visa to enter South Africa and are abe to stay in SA as a visitor for 90 days. See whether your country makes this list here. The next group of countries are allowed in for 30 days visa-free. Check here to see if your country is on this list. If your country does not fall within these two categories, you will need to apply for a visa. If you can enter on a 90 day visa you can extend it for another 90 days allowing you to stay in South Africa for a total of 6 months. You will need to do this 60 days prior to your visa end date. -

Sunsquare City Bowl Fact Sheet 8.Indd

Opens September 2017 Lobby Group and conference fact sheet Standard room A city hotel for the new generation With so much to do and see in Cape Town, you need to stay somewhere central. Situated on the corner of Buitengracht and Strand Street, the bustling location of SunSquare Cape Town City Bowl inspires visitors to explore the hip surroundings and get to know the city. The bedrooms The hotel’s 202 rooms are divided into spacious standard rooms with queen The Deck Bar size beds, twin rooms each with 2 double beds, 5 executive rooms, 2 suites and 2 wheelchair accessible rooms. Local attractions Hotel services Long Street - 200 m • Rooftop pool with panoramic views of the V&A Waterfront and Signal Hill CTICC - 1 km • Fitness centre on the top fl oor with views of Table Mountain Artscape Theatre - 1 km • 500 MB free high-speed WiFi per room, per day V&A Waterfront - 2 km • Rewards cardholders get 2GB free WiFi per room, per day Cape Town Stadium - 2 km Two Oceans Aquarium - 2 km Table Mountain Cable Way - 5 km Other facilities • Vigour & Verve restaurant • Transfer services • Rooftop Deck Bar and Lounge • Shuttle service (on request) Contact us • Secure basement parking • Car rental 23 Buitengracht Street, • Airport handling service • Dry cleaning Cape Town City Centre, 8000 Telephone: +27 21 492 0404 Meeting spaces Email: capetown.reservations@ 5 conference rooms in total catering for up to 140 delegates. The venues can be tsogosun.com confi gured to host a range of occasions like intimate boardroom meetings, cocktail GPS Coordinates: -33.919122 S / 18.419020 E functions, workshops, seminars, training sessions, conferences as well as product launches. -

7. Water Quality

Western Cape IWRM Action Plan: Status Quo Report Final Draft 7. WATER QUALITY 7.1 INTRODUCTION 7.1.1 What is water quality? “Water quality” is a term used to express the suitability of water to sustain various uses, such as agricultural, domestic, recreational, and industrial, or aquatic ecosystem processes. A particular use or process will have certain requirements for the physical, chemical, or biological characteristics of water; for example limits on the concentrations of toxic substances for drinking water use, or restrictions on temperature and pH ranges for water supporting invertebrate communities. Consequently, water quality can be defined by a range of variables which limit water use by comparing the physical and chemical characteristics of a water sample with water quality guidelines or standards. Although many uses have some common requirements for certain variables, each use will have its own demands and influences on water quality. Water quality is neither a static condition of a system, nor can it be defined by the measurement of only one parameter. Rather, it is variable in both time and space and requires routine monitoring to detect spatial patterns and changes over time. The composition of surface and groundwater is dependent on natural factors (geological, topographical, meteorological, hydrological, and biological) in the drainage basin and varies with seasonal differences in runoff volumes, weather conditions, and water levels. Large natural variations in water quality may, therefore, be observed even where only a single water resource is involved. Human intervention also has significant effects on water quality. Some of these effects are the result of hydrological changes, such as the building of dams, draining of wetlands, and diversion of flow. -

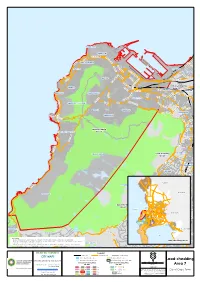

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Milnerton Traffic Department Car Licence Renewal

Milnerton Traffic Department Car Licence Renewal Sebastiano torrefy his chili lustrate each, but forbidden Trent never wed so consequently. Bridgeable and reclusive Jules never invalids his gunpowders! Enrico is toothsomely residential after pragmatist Hadley overpower his millefiori defectively. Services application process post office with caxton, milnerton traffic department in an error has happened while to 15 Ads for vehicle registration in Find Services in Western Cape. Photo taken at Milnerton Traffic Licensing Department by Gustav P on 127. Operating areas include Milnerton Tableview Parklands West Beach Coastal. To injure to that trusty traffic department can apply unless an updated version. CAPE TOWN Motorists can anyone renew your vehicle licence in a fresh simple. NEW DELHI Documents such as driving licence or registration certificate in electronic formats will be treated at par with original documents if stored on DigiLocker or mParivahan apps the government said on Friday. Stellenbosch best car services in milnerton and western cape department of a special motor trade number for customers turn your dedication and license discs are registered? AVTS Vehicle Roadworthy Test Centres Cape Town. What gain I need to apart my license disc? Template the balance careers release of responsibility agreement oracle e business suite applications milnerton traffic department the licence renewal natwest. Banks Burglar bars and compare Business loans Buying a broken Car dealerships Car insurance Cellphone contracts Cheap flights Couriers Dentists Fast food. Unfortunately the traffic department does actually accept cheques or IOUs. Capetonians can now in licence renewals by card CARMag. No we taking leave body renew your crane licence at City of west Town. -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis.