Chronicles of Brunonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MVSC-F099.4-K16.Pdf

[PAGE 1] KANSAS CITY CALL TENTH ANNIVERSARY AND PROGRESS EDITION Vol. 10 No. 13 Kansas City, Mo., July 27, 1928. PROGRESS THE PROGRESS of Negroes in the United States is so great that history will point out what you have done as one of the achievements which mark this age. Your rise is one of the best proofs of the value of the American theory of government. Successes by individuals here and there have been multiplied until now yours is a mass movement. You are advancing all along the line, a sound basis for your having confidence in the future. The world’s work needs every man. I look to see the Negro, prepared by difficulty, and tested by adversity, be a valued factor in upbuilding the commonwealth. In the Middle West, where The Kansas City Call is published, lies opportunity. In addition to urban pursuits you have available for the man of small means, the farm which is one of the primary industries. The Negro in your section can develop in a well rounded way. Above all things, take counsel of what you are doing, rather than of the trials you are undergoing. Look up and go up! Julius Rosenwald [page 2] “PROGRESS EDITION” CELEBRATING THE KANSAS CITY CALL’S TENTH ANNIVERSARY Kansas City, Missouri, Friday, July YOU ARE WELCOME! The changes in The Kansas City Call’s printing plant are completed. We now occupy 1715 E. 18th street as an office; next door at 1717 is our press room and stereotyping room; upstairs is our composing room; in the basement we store paper direct from the mill. -

Office of the President | Brown University

Office of the President | Brown University HOME ABOUT BROWN ADMINISTRATION OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT Office of the President Facts About Brown Welcome to Brown University, the third oldest History institution of higher education in New England and Mission seventh oldest in the United States. Founded in 1764, Brown has throughout the decades represented the best President's Report 2012 (PDF) Administration in liberal arts education and leading edge scholarship President and research. Biography As you explore the University’s website, you will get a Contact Information glimpse of the wealth of offerings and people who contribute to a unique academic culture, one that Letters and emphasizes individual innovation and achievement President Ruth Simmons Announcements while underlining the value of mining the diversity of Organizational Chart Brown by pursuing interdisciplinary efforts and fostering intellectual exchange across cultures and perspectives. You will also see that Brown is a university with a Past Presidents long and rich history, one that in each era has reflected the strength of the founders’ Photos and Videos commitment to educating students for a life of “usefulness and reputation.” Today, our students, faculty, alumni and staff demonstrate this commitment to society in a Presidential Hosts wide range of engagements that make a difference throughout the world. Select News Items The primary campus, located on the historic East Side of Providence, contains Staff museums, art galleries, libraries, and beautiful historic buildings. More recently, Student Office Hours the University has expanded its campus into Providence’s downtown and Jewelry District, an appealing new aspect of our growing campus. This expansion has Additional Links important consequences for the economic health and growth of the city and state. -

Transcript – Dorothy Allen Hill

Transcript – Dorothy Allen Hill Narrator: Dorothy Allen Hill Interviewer: Interview Date: Interview Time: Location: Length: 2 audio files; 54:30 Track 1 Dorothy Allen Hill: [00:00] (inaudible) in ’28. Q: Oh, really? DAH: Nineteen twenty-eight, mm-hmm. (inaudible) University of Rhode Island, (inaudible). But my uncle and my aunt both (inaudible). Q: Oh, your aunt? DAH: And my uncle, mm-hmm. Q: And when did she graduate? DAH: Nineteen hundred, and he was 1904. Q: From Brown? DAH: Yes, mm-hmm. Q: And what was her name? DAH: Mary Hill, (inaudible). 1 Q: (inaudible). DAH: (inaudible) [Harrison B?] – there was a Harrison [Gray?] and there was a Harrison [Buckley?], (inaudible). Q: All right. Well, was there a women’s college at that time? DAH: Yes, the Women’s College, I think, began in, I think it would be, the 1890s. Not many classes had graduated before my aunt – perhaps five or six. It was very small. Q: It must have been a privilege [01:00] (inaudible). DAH: Yes, I mean, I’m sure she was very proud to be at Brown. They had to (inaudible) classes. Almost all her classes were on the [men’s campus?]. And the men were not a bit pleased to have women there, in general. (laughter) They felt sort of unwanted, I think. But the faculty was very happy (inaudible). Q: Do you know what she took? (inaudible)? DAH: She majored in English, but I can’t really tell you anything else. Q: (inaudible)? DAH: I don’t think she, it was a fact…She commuted, of course, (inaudible). -

Brown University Brown University

new edition Brown University Through nearly three centuries, Brown University has taken the path less traveled. This is the story of the New England college that became a twentieth-century leader in higher education by Brown University making innovation and excellence synonymous. O A Short Histor A Short History - by janet m. phillips y phillips Brown University A Short History - by janet m. phillips Office of Public Affairs and University Relations Brown University All photos courtesy of Brown University Archives except as noted below: John Forasté, Brown University: pp. 75, 77, 84, 86, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 98, 101, 103, 107, 110, 113, 115. John Abromowski, Brown University: p. 114. Michael Boyer, Brown University: p. 83. Brown University Library, Special Collections: p. 38. Billy Howard: p. 102. John C. Meyers: p. 45. Rhode Island Historical Society: pp. 22, 51. David Silverman: p. 64. Bob Thayer: p. 12. Design and typography: Kathryn de Boer Printing: E.A. Johnson Company Copyright © 2000, Brown University All Rights Reserved on the cover: College Edifice and President’s House. A colored Office of Public Affairs and University Relations reproduction, circa 1945, of the Brown University circa 1795 engraving by David Providence, Rhode Island 02912 Augustus Leonard. September 2000 k Contents Editor’s Note 4 Acknowledgments 5 1 Small Beginnings, Great Principles: A College 7 for the Colony 2 Breaking the Seal: Revolution and Independence 17 3 Old Systems and New: The Search for Identity 33 4 Building a University 49 5 The Modern Era 67 6 The International University 85 7 Toward the New Millennium 99 8 New Horizons 111 Bibliography 116 Interesting sidelights Commencement 12 about selected people, Nicholas Brown Jr., 1786 20 activities, and traditions Horace Mann, 1819 27 Samuel G. -

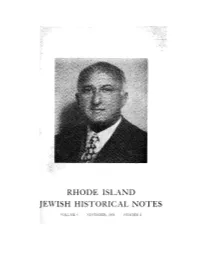

Volume 4 November, 1964 Number 2 Front Cover Honorable Philip C

RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL NOTES VOLUME 4 NOVEMBER, 1964 NUMBER 2 FRONT COVER HONORABLE PHILIP C. JOSLIN 1886-1961 First President of Temple Emanu-El 1924-1948 Honorary President 1948-1961 RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL NOTES VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2 NOVEMBER, 1964 Copyright November, 1964 by the RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 209 ANGELL STREET, PROVIDENCE 6, RHODE ISLAND RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 209 ANGELL STREET, PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS OF TEMPLE EMANU-EL .... 3 EARLY EXPONENT OF PHYSICAL FITNESS 89 ISAAC MOSES: A COLORFUL RHODE ISLAND POLITICAL FIGURE . .113 HAYS WAS A PATRIOT . '. 126 NECROLOGY . 127 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS OF THE ASSOCIATION: DAVID C. ADELMAN President BERYL SEGAL Vice President JEROME B. SPUNT Secretary MRS. LOUIS I. SWEET .Treasurer MEMBERS-AT-LARGE OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE FRED ABRAMS MRS. SEEBERT J. GOLDOWSKY ALTER BOYMAN MRS. CHARLES POTTER RABBI WILLIAM G. BRAUDE LOUIS I. SWEET SEEBERT J. GOLDOWSKY, M.D. MELVIN L. ZURIER SEEBERT JAY GOLDOWSKY, M.D., Editor Printed in the U. S. A. by the OXFORD PRESS, INC., Providence, Rhode Island THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS OF TEMPLE EMANU-EL By RABBI ISRAEL M. GOLDMAN* *This is a continuation of the story of Temple Emanu-El by (Rabbi Goldman, the first five chapters of which appeared in the Notes for May, 1963 (Vol. 4, No. 1). Rabbi Goldman was the first Rabbi of Temple Emanu-El and served from 1925 to 1948. He is presently Rabbi of the iChizuk Amuno Congregation in Baltimore, Maryland. CHAPTER VI "IN THE DAY OF ADVERSITY, CONSIDER" The author of the Book of Ecclesiastes in the 14th verse of the seventh chapter offers this wise counsel: "In the day of prosperity, re- joice; But in the day of adversity, consider." These words have a special pertinence in the history of Temple Emanu-El. -

American Baptist Foreign Mission Society 1932

American Baptist Foreign Mission Society 1932 ONE-HUNDRED-EIGHTEENTH A N N U AL REPORT Presented by the Board o f Managers at the Annual Meeting held in San Francisco, California, July 12-17,1932 Foreign Mission Headquarters 152 Madison Avenue New York Printed by THE JUDSON PRESS 1 701-1703 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, Pa. CONTENTS PAGE O F F IC E R S ...................................................................................................................... 5 GENERAL AGENT, STATE PROMOTION DIRECTORS 6 B Y -L A W S ....................................................................... 7-9 P R E F A C E ...................................................................................................................... 11 GENERAL REVIEW OF THE Y E A R ....................................................... 13-62 I ntroduction ......................................................... ................................................ 15 T h e W orld S it u a tio n ...................................................................................... 15 H istory R epeats I tself .................................................................................... 18 T h e I n exorable P ressure of t h e W orld D epression .................... 19 T h e C onference on D is a r m a m e n t ........................................................... 20 A M essage on t h e J a p a n -C h i n a C r i s i s ................................................. 22 W a r D evastation a t S h a n g h a i ................................................................ 23 A G rave Cr isis for t h e U n iversity of S h a n g h a i ............................. 23 F lood R elief in C h i n a .................................................................................... 25 I nterpreting t h e C h r is t ia n C risis i n C h i n a ...................................... 26 T h e K ingdom of God M ovem ent in J a p a n .........................................