Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MWG Covid-19 USAR Response Technical Guidance Note

INSARAG MEDICAL WORKING GROUP COVID-19 DEPLOYMENT TECHNICAL GUIDANCE NOTE Date: March 2021 1 Table of Contents 1. Purpose .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 3. Personal Protective Equipment ......................................................................................... 5 4. Activation ........................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Go / No Go Deployment Decision .............................................................................. 8 4.2 Embedded Personnel ................................................................................................. 8 5. Mobilisation ....................................................................................................................... 9 5.1 Medical Intelligence Gathering .................................................................................. 9 5.2 Arrival at Check-in Area ........................................................................................... 10 5.3 COVID-19 Pre-deployment Screening Questionnaire .............................................. 11 5.4 Pre-deployment Medical Screening......................................................................... 11 5.5 Pre-deployment COVID-19 Testing ......................................................................... -

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and COVID-19: FDA Regulation and Related Activities

Updated September 22, 2020 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and COVID-19: FDA Regulation and Related Activities The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has Regulatory requirements vary by type of PPE, which are affected the medical product supply chain globally and generally class I or II devices. domestically. The impact of COVID-19 on the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, Medical Gloves gloves, respirators, and surgical masks, for health care Medical gloves are used to protect the wearer from the personnel continues to be a concern. spread of infection during medical procedures and examinations. Medical gloves are class I devices that PPE is generally worn by health care personnel to protect require a 510(k) clearance, and include patient examination the wearer from infection or illness from blood, body fluids, gloves (21 C.F.R. §880.6250) and surgical gloves (21 or respiratory secretions. In the United States, PPE intended C.F.R. §878.4460). for use in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease meet the definition of a medical device (device) Medical Gowns under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) Medical gowns (21 C.F.R. §878.4040) are a type of surgical and are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug apparel used to protect against infection or illness if contact Administration (FDA) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). PPE that do not meet the FFDCA with infectious liquid or solid material is likely. definition of device (i.e., not intended for medical use) are Manufacturers are encouraged to comply with national not regulated by FDA. -

Surgical Gowns Input Producers

SURGICAL GOWNS INPUT PRODUCERS CONTACT Supply Chain Classification Additional Information Resin Nonwoven Woven/Knit Fabric Yarn Company Location Country Name Title Email Phone Comments and/or Fiber Other Column1 Director of Quinter Textile North Brandon Business brandon@quintertex Contract Group Carolina USA Moore Development tile.com (704) 467-5136 cut & sew ARifkin is a bag manufacturer that covers a wide spectrum in the commercial sector. We also manufacture mattress covers for commercial use. Our sister facility is Hope manufacturing, we produce uniforms, pants, Pennsylva Paul shirts and jackets. We have a talented and diverse workforce that is ARifkin nia USA Lantz COO [email protected] 570-357-1686 available to work during this pandemic outbreak. X X Joseph Ballantyne & North Ballantyn joeb@ballantyneass Associates Carolina USA e President ociates.com; 215-519-8074 X X Noble Biomaterials, Inc. is a global leader in antimicrobial and conductivity Note, Noble Biomaterials produces solutions for soft surface applications. Noble produces silver-based antimicrobial yarn, staple fiber, fabric, and Senior Vice advanced material technologies designed for mission critical applications in Medical foam products in the US that have been or Noble Biomaterials Pennsylva Bennett President of bfisher@noblebioma the performance apparel, healthcare, industrial, and emerging wearable antimicro could be applied for these various Inc. nia USA Fisher Sales terials.com; 828-443-4217 technology markets. X X X X bial foam applications. L & J AWNINGS & LUIS SHADE GONZALE [email protected] STRUCTURES INC. Florida USA Z M; 407-920-4343 plastic parts and paints for medical QTEK LLC Michigan USA Bowen Li President [email protected]; 906-281-7082 X X devices We can apply antimicro bial, FR, Skip skipgehring@gehring and bug Custom manufacturer of many different Gehring-Tricot Corp New York USA Gehring President/CEO textiles.com; 516-474-5726 X repellant items Although, we’re a startup company the owner has years of experience as a Finder putting together deals when no one else can. -

PPE in Hospital

Philippine COVID-19 Living Clinical Practice Guidelines Institute of Clinical Epidemiology, National Institutes of Health, UP Manila In cooperation with the Philippine Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Funded by the DOH AHEAD Program through the PCHRD EVIDENCE SUMMARY Among health care workers how effective is the use of personal protective equipment in the wards, ICU, and emergency room in the prevention of COVID 19 infection? Evidence Reviewers: Germana Emerita V. Gregorio, MD, Rowena F. Genuino, MD, MSc, Howell Henrian G Bayona, MSc, CSP-PASP PPE in Hospital RECOMMENDATION We recommend the use of the following PPE: disposable hat, medical protective mask (N95 or higher standard), goggles or face shield (anti-fog), medical protective clothing, disposable gloves and disposable shoe covers or dedicated closed footwear as an effective intervention in the prevention of COVID-19 among health care workers in areas with possible direct patient care of COVID-19 positive patients and aerosol generating procedures. (Moderate quality of evidence; Strong recommendation) Consensus Issues Direct patient care1 is defined as hands on, face-to-face contact with patients for the purpose of diagnosis, treatment and monitoring. This recommendation was made by the panel as it prioritized giving the best available protection to the healthcare workers. Whenever possible, hospital administrators should invest in these PPEs. Strict adherence to the appropriate use of PPEs must be observed even if healthcare workers have already been vaccinated against COVID-19. 1 National Center for Emerging, Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases- Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. (2020). The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Manual- Healthcare Personnel Safety Component Protocol: Healthcare Personnel Exposure Module. -

Instructions to All Major and Minor Ports for Dealing With(COVID-19)

भारत सरकार/ GOVERNMENT OF INDIA पोत पररवहन मĂत्रालय / MINISTRY OF SHIPPING नौवहन महाननदेशालय, मबुĂ ई DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF SHIPPING, MUMBAI F. No. 7-NT(72)/2014 Date: 20.03.2020 DGS Order No. 04 of 2020 Subject: Instructions to all major and minor ports for dealing with novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic - reg. 1. The Directorate has issued instructions on dealing with novel coronavirus (COVID- 19) vide DGS Order No. 02 of 2020 dated 16.03.2020, DGS Order No. 03 of 2020 & 20.03.2020 and maritime advisories vide M.S. Notice 02 of 2020 dated 28.01.2020, M.S. Notice 03 of 2020 dated 04.02.2020 & M.S. Notice 06 of 2020 dated 03.03.2020 (F. No. 7- NT(72)/2014). 2. The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic across large number of nations is an unprecedented situation in recent times. To slow the spread of the disease and mitigate its impacts, travel advisories have been issued by many jurisdictions including India. However, shipping services are required to continue to be operational so that vital goods and essential commodities like fuel, medical supplies, food grains etc., are delivered and to ensure that the economic activity of the nation is not disrupted. It is, therefore, important that the flow of goods by sea should not be needlessly disrupted without compromising the safety of life and protection of the environment. In view of the same, it has been decided that for the continued operation of vessels and ports, the following shall be complied with by all stakeholders till further orders. -

CORONAVIRUS SARS-Cov-2 INFECTION: Chinese Pharmaceutical Association

CORONAVIRUS SARS-CoV-2 INFECTION: Expert Consensus on Guidance and Prevention Strategies for Hospital Pharmacists and the Pharmacy Workforce (2nd Edition) Chinese Pharmaceutical Association Feb 12th, 2020 Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Expert Consensus on Guidance and Prevention Strategies for Hospital Pharmacists and the Pharmacy Workforce (2nd Edition) Contents 1 Background ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Epidemiology ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Etiology ............................................................................................................ 2 2 Clinical manifestations and diagnosis ......................................................................... 2 2.1 Clinical manifestations..................................................................................... 2 2.2 Clinical diagnosis ............................................................................................. 2 2.3 Clinical classification ....................................................................................... 3 3 Treatment .................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Characteristics and precautions of treatment options ...................................... 4 3.2 Pharmaceutical care ......................................................................................... 9 3.3 Traditional -

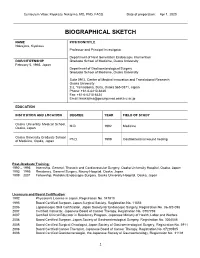

Biographical Sketch Format Page

Curriculum Vitae: Kiyokazu Nakajima, MD, PhD, FACS Date of preparation: Apr 1, 2020 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH NAME POSITION/TITLE Nakajima, Kiyokazu Professor and Principal Investigator Department of Next Generation Endoscopic Intervention DOB/CITIZENSHIP Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University February 5, 1965, Japan Department of Gastroenterological Surgery Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University Suite 0912, Center of Medical Innovation and Translational Research Osaka University 2-2, Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan Phone: +81-6-6210-8420 Fax: +81-6-6210-8424 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION INSTITUTION AND LOCATION DEGREE YEAR FIELD OF STUDY Osaka University Medical School, M.D. 1992 Medicine Osaka, Japan Osaka University Graduate School Ph.D. 1999 Gastrointestinal wound healing of Medicine, Osaka, Japan Post-Graduate Training: 1992 – 1993 Internship, General, Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Osaka University Hospital, Osaka, Japan 1993 – 1995 Residency, General Surgery, Nissay Hospital, Osaka, Japan 1999 – 2001 Fellowship, Pediatric/Endoscopic Surgery, Osaka University Hospital, Osaka, Japan Licensure and Board Certification: 1992 Physician’s License in Japan, Registration No. 347810 1995 Board Certified Surgeon, Japan Surgical Society, Registration No. 11553 2006 Laparoscopic Skill Certification, Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery, Registration No. 06-GS-098 2007 Certified Instructor, Japanese Board of Cancer Therapy, Registration No. 0707769 2007 Certified Clinical Educator in Residency Program, Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2008 Board Certified Surgeon, Japan Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Registration No. 3004046 2008 Board Certified Surgical Oncologist, Japan Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Registration No. 3911 2008 Board Certified Cancer Therapist, Japanese Board of Cancer Therapy, Registration No. 07200505 2008 Board Certified Gastroenterologist, the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, Registration No. -

16 July 2020 DOCUMENT AC/338-D(2020)0087 SILENCE

NATO UNCLASSIFIED 16 July 2020 DOCUMENT AC/338-D(2020)0087 SILENCE PROCEDURE ENDS: 13 August 2020 17:00 CET AGENCY SUPERVISORY BOARD IDENTIFICATION OF NATIONAL PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE) SOURCES Note by the Chairperson REFERENCES: A. AC/338-D(2020)0049, 20 March 2020 & AS1, 27 March 2020 B. AC/338-D(2020)0049-REV1, 29 May & AS1, 24 June 2020 C. AC/338-D(2020)0049-REV2, 24 June 2020 & AS1, 30 June 2020 D. G/2020/516, 15 July 2020 (enclosed) 1. At Reference A, the Board approved the General Manager's request for a blanket authorisation, ending 30 June 2020, for the supply of materiel originating from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in support of requests related to COVID-19 containment efforts. 2. At Reference B, the General Manager sought the ASB's agreement to extend the current authorisation to 31 December 2020, but the United States was unable to approve the document and broke silence, indicating they could agree to an extension until 30 September 2020 in order to give Allies and NSPA time to find alternative suppliers. This proposal was approved by the Board at Reference C. 3. In light of the above, the Agency has initiated negotiations with those companies that have been awarded outline agreements for the procurement of Personal Protective Equipment, with the aim of identifying new sources of supply outside PRC to cope with future requirements. 4. With the letter at Reference D, the Agency is seeking to invite Nations to identify their national manufacturers of PPE products (as listed at Annex) in order to support Nations’ requirements by competing and awarding future contracts with firms located within NATO Nations. -

Beximco Health PPE Catalogue

HEALTH Personal Protective Equipment Product Catalogue 08.2020 Beximco Health The health of your people, your customers and your business has never been greater. We understand that you need quality, certified protective clothing that works, delivered fast at the right cost. That’s because we have the manufacturing know-how mixed with PPE expertise you can rely on. Take a look at our range of products and get in touch to see how we can work together. We look forward to working with you. 2 3 Contents Gowns Gowns 06-15 Disposable Gowns. Coveralls 16-18 Beximco Health has a range of gowns Respirators and Surgical Masks 19-23 to provide complete peace of mind Shoe Covers 24-25 whatever the task. Headwear 26-27 Civilian Masks 28-35 Face shield 36-39 Protective Glass 40-43 4 35 AD923 Gown Sizing Reusable S – 3XL – 2 sizes Medical Gown Point of measure (Inches) S/M/L XL/2XL/3XL Length 42 45 AD923 1/2 chest 22 26 Sweep 22 26 CottonPoly 150gsm Sleeve length 25 3/8 26 3/8 Tie lengths at back of neck 18 18 Reusable Medical Gown Tie lengths at centre front waist 35 each 35 each Ordering details Part Number Description AD923 Reusable Medical Gown Applications • Suitable for general use Product marking Manufacturer Beximco Key features Description Medical Gown Part Number AD923 • Rugged and durable fabric • Soft and comfortable feel Symbols Medical Device Non-sterile • Designed to protect against particles and droplets Certification AAMI PB70 Level 1 • 2 fabric neck ties Shelf Life 5 years • Water repellent Expiry Date e.g. -

Attachment- 03 Medical Gown

6/3/2020 Medical Gowns | FDA Medical Gowns Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) (/emergency-preparedness-and-response/counterterrorism- and-emerging-threats/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19) Surgical Mask and Gown Conservation Strategies - Letter to Healthcare Providers (/medical-devices/letters-health-care-providers/surgical-mask-and-gown- conservation-strategies-letter-health-care-providers) FAQs on Shortages of Surgical Masks and Gowns (/medical-devices/personal-protective-equipment-infection-control/faqs-shortages-surgical-masks- and-gowns-during-covid-19-pandemic) CDC Prevention and Treatment (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/prevention-treatment.html) Healthcare Supply of Personal Protective Equipment (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/healthcare-supply-ppe.html) Recalled Cardinal Health Surgical Gowns and Procedure Packs Medical device manufacturer Cardinal Health sent urgent medical device recall letters to its customers for some of its Level 3 surgical gowns and PreSource Procedure Packs that contain those gowns. For the list of affected gowns (sizes, item codes, catalog numbers, and lot numbers or lot codes), please see the FDA’s Medical Device Recalls database information on the recalled gowns (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfRES/res.cfm? start_search=1&event_id=&productdescriptiontxt=&productcode=fya&IVDProducts=&rootCauseText=&recallstatus=¢erclassiøcationtypetext=&recallnumber=&postda and recalled packs (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfRES/res.cfm? start_search=1&event_id=&productdescriptiontxt=&productcode=lro&IVDProducts=&rootCauseText=&recallstatus=¢erclassiøcationtypetext=&recallnumber=&postdat For more information, see the January 2020 statement from Jeff Shuren, M.D., J.D., director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, on quality issues with certain Cardinal Health surgical gowns and packs (/news-events/press-announcements/statement-quality-issues-certain-cardinal-health-surgical- gowns-and-packs). -

Qso-20-17-All (Pdf)

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 7500 Security Boulevard, Mail Stop C2-21-16 Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850 Center for Clinical Standards and Quality/Quality, Safety & Oversight Group Ref: QSO-20-17-ALL DATE: March 10, 2020 TO: State Survey Agency Directors FROM: Director Quality, Safety & Oversight Group SUBJECT: Guidance for use of Certain Industrial Respirators by Health Care Personnel Memorandum Summary • The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) CMS is committed to taking critical steps to ensure America’s health care facilities are prepared to respond to the threat of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other respiratory illnesses. • The memo clarifies the application of CMS policies in light of recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance expanding the types of facemasks healthcare workers may use in situations involving COVID-19 and other respiratory infections. Background CMS is committed to taking critical steps to ensure America’s health care facilities are prepared to respond to the threat of the COVID-19 and other respiratory illness. With this announcement, health care workers in providers and suppliers certified by CMS will have a more expansive range of options to protect themselves and those receiving their care. CMS will continue to explore flexibilities and innovative approaches within our regulations to allow health care entities to meet the critical health needs of the country. Guidance The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have updated their Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) recommendations for health care workers involved in the care of patients with known or suspected COVID-19. -

AHD COVID-19 School Nurses

COVID-19 Information for School Nurses What is COVID-19 (2019 novel coronavirus)? The Anchorage Health Department (AHD) is monitoring an outbreak of respiratory illness caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). The virus, first detected in China in December 2019, spreads from person-to-person and has the potential to cause severe illness and death. Four well-known strains of coronaviruses regularly circulate in human populations globally and are a frequent cause of upper respiratory infections. COVID-19 is new, so it’s called novel coronavirus. What is occuring in Alaska? AHD is working with local, state, and federal healthcare partners in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. There are no confirmed cases in Anchorage or Alaska. The Anchorage Health Department is coordinating with schools, hospitals, local healthcare partners and the emergency medical system to ensure a uniform and swift response if a case is suspected or identified in Anchorage. How does the COVID-19 virus spread? Much is unknown about how COVID-19 spreads. Current knowledge is largely based on what is known about similar coronaviruses. Other coronaviruses spread from an infected person to others through: respiratory droplets via coughing and sneezing, close personal contact such as touching or shaking hands, touching an object or surface with the virus on it, then touching your mouth, nose, or eyes. What are the symptoms of COVID-19? Fever >100.4°F Cough Shortness of Breath Symptoms include fever (>100.4°F), cough and shortness of breath and may appear in as few as 2 days or as long as 14 days after exposure.